“Hoover proclaimed his political support for the Committee on Un-American Activities and its members in the war on communism. They were no a team.”—Tim Weiner, Enemies, 149.

The question of how linked the relationship was between the FBI and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) is to me one of the most interesting questions that can be asked of this period. By law they were two very different organizations falling under two very different departments. The HUAC was a congressional committee tasked with investigating and trying Americans who were allegedly guilty of subversive activities and allegiances. The organization was founded in the late 1930s and during its almost forty years of existence issued thousands of subpoenas and sentenced hundreds to jail for contempt of court (for refusing to answer the infamous question “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?”) The FBI on the other hand was a crime fighting institution that fell under the jurisdiction of the Department of Justice rather than Congress. The question remains, how closely were these two organizations linked in their shared objectives?

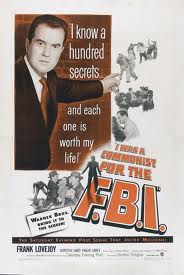

As mentioned in a previous post, it was not uncommon for someone seated before the HUAC to find the committee members armed with the defendant’s entire FBI file. This was the heart of the link between these organizations. The FBI could go about their covert techniques of gathering information, but could now channel it to the HUAC for use as anonymously provided evidence against the defendant. Tim Weiner writes. “The FBI would gather evidence in secret, working toward the “unrelenting prosecution” of subversives. The committee would make its greatest contribution through publicity—what Hoover called ‘the public disclosure of the forces that threaten America.’”[1] This link would remain mostly secret from the public for many years.

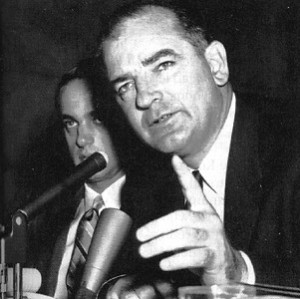

It was not until the early 1950s that the HUAC, under the infamous Senator Joseph McCarthy, hit the peak of its anti-communist rhetoric and action. William Sullivan, the high ranking FBI official who has been mentioned many times before in this blog wrote in his

memoir, “During the Eisenhower years the FBI kept Joe McCarthy in business. Senator McCarthy Stated publicly that there were Communists working for the State Department. We gave McCarthy all we had, but all we had were fragments, nothing could prove his accusations. For a while, though, the accusations were enough to keep McCarthy in the headlines.”[2] This quote, if Sullivan’s book is indeed accurate, changes the picture a little bit. Rather than two titan organizations teaming up in order to fight communism in America, we get the image of the commonly used analogy of FBI as the puppet master. Rather than being a productive organization on its own, Sullivan’s account makes it seem as if the HUAC was nothing more but an assassin of public opinion ready to attack and besmirch the public image of anyone the FBI had dirt on. Despite the fact that J. Edgar Hoover was obsessed with the public’s opinion of the Bureau, it is clear that he preferred to leave the dirty work of public accusations to people who did not mind getting their hands dirty. Luckily, the HUAC was desperate for information and more than willing to provide that service.