First Tuchman, now Marius. This is the second time I’ve read an academic horror story in which someone becomes so wrapped up in research that s/he never gets around to writing. Tuchman recalls “a lady professor” in her seventies who had been doing research all her life. Marius, too, writes of Frederick Jackson Turner, who was only able to write one of the many books he had promised to publishers (A Short Guide to Writing About History, 88-89). These individuals – both the lady professor and Turner – knew so much, but were they ever able to share even a fraction of their knowledge with the world? Tuchman is right when she says “Research is endlessly seductive; writing is hard work” (Practicing History,21).

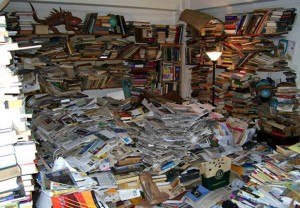

The black hole of death. Stop researching or you might end up on an episode of Hoarders. From http://www.oddballdaily.com/.

I was somewhat afraid of following in their footsteps and becoming a perpetual researcher while doing our archive assignment. As I explored the collection of General James Gordon Steese – Dickinson College Class of 1902, Army engineer, WWI witness, Panama Canal builder, Alaska Road Commissioner, Prospector of South American oil, and all around adventurer and world traveler – I was amazed at what I found. The artifacts included a flirty goodbye letter from 1910 made with magazine scraps; an elaborate certificate signed by Presidents Roosevelt and Taft; and photographs of men wrangling alligators and sea lions, among other items. Still, with twelve plus boxes of documents pertaining to some of the most important events of the first half of the twentieth century in front of me, it wasn’t too hard to see how the situation could turn from an interesting class assignment into a black hole of death. Once I’d rummaged around a bit and picked four fairly interesting pieces (but oh, there were so many!), I got out of there, knowing that my incredible ability to get distracted would get me nowhere.

I also found that recording not just my findings, but also my thoughts and questions as I went was really helpful both to guide my research and simplify the end task. I’ve realized that it’s important to be conscientious of your thought and not let yourself slip into that sort of absentmindedness that comes with casual reading. Thoughts are fleeting, tie them down to a piece of paper so that they don’t disappear into your nether regions of your brain again! Writing as I went made putting the whole piece together at the end that much easier. Writing is a process. This is something that we’re constantly told but, at least for me, is a lesson I’ve had to learn the hard way and am only now beginning to understand and apply. So here’s to knowing when to stop researching and start writing, to the writing process, and to our ability to change, learn, and grow from it!