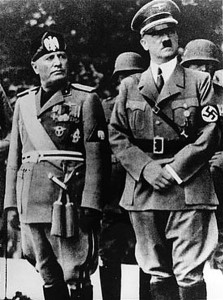

Dictators. We tend to think of Hitler and Mussolini as having similar ideals and regimes based on the sole fact that they are both dictators. However, when analyzing their doctrines’ theories, one can see their goals and philosophies were not similar. In Hitler’s The 25 Points 1920: An Early Nazi Program the focus is on the purification of Germany. Contrastingly, in Benito Mussolini: What is Fascism, the focus is on the State’s importance exercised through expansion.

Mussolini’s fascist state focuses on the State’s absolutism, expansion, and emphasis on man’s character. Mussolini came from a socialist background as an editor for a socialist newspaper. Once appointed Prime Minister in 1922, his career began in state leadership. In Mussolini’s What is Fascism he placed an emphasis on heroism of the man. He, as the spokesperson of the Fascist regime, believed man should not have any economic motive but rather see life as “duty and struggle and conquest”. For what purpose should man be dutiful and charismatic? The State, of course! Mussolini believed the State was the foundation of Fascism. As man provides ethics (discipline, duty, sacrifice), the State is able to expand.

Hitler’s philosophy focuses on maintaining the German population in all aspects. From the formation of a national army to restrictions on immigration, the Nazi program aimed to unify the Germans into one single ideal of biology, culture, policy, and geography. They attained this by an emphasis on nationality. Although in The 25 Points there is a demand of land and/or colonization for the German people, the physical land is not a central point. Rather, the significance is this sense of German priority. Contrasting to Mussolini and Fascism, the Nazi party placed an emphasis on economy. Hitler demanded nationalization of some industries and a division of profits for others.

The collective priority of the State over the individual is shared between both Mussolini and Hitler. Although they achieved “common good” differently through their individual philosophies and actions, the overarching concept of commonality is evident in both regimes.

Mussolini demands the deprivation of “all useless and possibly harmful freedom” but the retention of essential liberty. What are some examples of “useless freedom”? Do you think it is possible to place such a specific margin of liberty on a population?