In the first four chapters of his text Dark Continent, Mark Mazower not only elaborates on the events of Europe’s interwar period, going into detail about the reasons for the development of these events, he also gives his readers an objective and analytical view on the continent as a whole. As opposed to going through Europe’s interwar period country by country, Mazower structures his chapters around the main issues and developments that affected all of Europe. Mazower pushes the idea that the countries of Europe progressed simultaneously with different ideological goals, but using similar means to achieve these goals. While Mazower occasionally strays away from his main points and sites more secondary sources than primary ones, he gives a new prospective on Europe at a volatile point in its history, explaining how even those countries that seem extreme in hindsight, differed in their methodology and ideology only slightly from the rest of the continent.

The examining of Europe as an entity, and not each individual European country during the Interwar period, really adds to the ingenuity Mazower’s text. He showed the developments throughout Europe that led to such events as the rise of Nazi Germany and the Russian Revolution, and that the formation of these governments was not as sudden or surprising as is commonly thought. For example, Eugenics, invoking such tactics as sterilization, was alive in the majority of European countries, as well as The United States, at the time; the Nazis just took the next step in purifying their population by killing those that they deemed undesirable (97). As for the Bolsheviks, Lenin introduced a “New Economic Policy” in the 1920’s that allowed from some forms of capitalism, such as private business, in Russia (117).

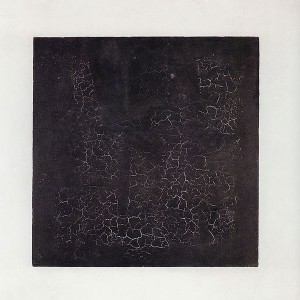

In the back of his text, Mazower lists his sources, as well as providing the reader with charts and maps that help to clarify his relatively dense writing. Maps, for example, that show the countries of European before and after the First World War, giving the reader a better idea of what he is discussing, such as invasions and minority issues within countries. In his bibliography, Mazower sites numerous sources, ranging in date from before the First World War to the 1990’s. While this use of sources from through out the twentieth century brings the perspectives of different time periods into the text, Mazower uses more secondary sources than primary ones, which effectually distances his text from the historical evens themselves.

While Mazower’s writing can become dense and hard to follow at times, for the most part, this text is clear and accessible to undergraduate students. A basic knowledge of European history would improve a reader’s comprehension of this text because major events and facts are skimmed over, so as to focus on the details and driving forces behind these events more intently. Mazower’s method of examining Europe as a whole sheds new light on a complicated and significant period in history, showing connections and common themes between countries that have been previously overlooked.

He would teach in Moscow for a time before dying St.Petersburg in 1935. Eventually, his grave was lost due to the rapid suburban expansion during and following the Second World War but his remains were rediscovered quite recently during construction in the area.

He would teach in Moscow for a time before dying St.Petersburg in 1935. Eventually, his grave was lost due to the rapid suburban expansion during and following the Second World War but his remains were rediscovered quite recently during construction in the area.