Between the years 1907-1917 Russia began changing, exploring new ideas and pushing boundaries with new forms of experimentation in it’s art. This change is known as the Avant-Grade movement. The movement consisted of young artist who had new views on the world, and ways to express these new ideas though art. The Avant-Grade movement called attention the real world, and rejected ideas of the mystical in their art. Gancharova, a leading member early in the movement produced a new “neo-primitive Russian style” with the use of angular silhouettes. Larionov, another leading member early in the movement was called the first Russian impressionist. With Ganchoarova and Larionov Russia began to surpass other European countries in the art world Larionov often said “the future is ours” and Ganchoarova stated “we are not a providence of Paris.” But the artist in the new movement often were faced with criticism, for example when Larionov and Gancharova organized an art exhibition many critics stated that the art work looked like it could have been painted by a donkey. Later a new group became central to the movement, this group was know as the Futurists, members of this group came from many divers backgrounds and therefore produced different styles of artwork. Futurist included poets, painters, and actors that would work together to produce new forms of art. Poets would write books of poetry, which would then be illustrated by painters creating a new exciting type of book where painters and poets mixed words with images. Stavinsky’s Rite of Spring, is another example of the artist braking away form the traditional art. Rite of Spring is a ballet that used different style then typical ballets. The set and costumes are filled with vibrant colors and the dancing are not as gracefully as what is typically thought of as ballet. Although the Avant-Grade movement was short lived in had a lasting impact on Russia and the rest of Europe.

Tag Archives: Avant Garde

Russian Avant-Garde

The Russian avant-garde movement represented the struggle between the past and the future. The explosion of Russian artistry from 1907 to 1917 turned away from the realism that appeared to have dominated the end of the nineteenth century (like that reflected in the work of the Wanderers) and presented an even greater level of experimentation. In contrast to realism, there was an increased focus on beauty and emotion, particularly in dance. An example of beauty “for beauty’s sake” can be seen in Diaghilev’s “Ballet Russes”, which included elaborate and colorful set design and costumes as a vital component of dance performances. In theater too, there was a break from “excessive realism”, as seen in the development of the Dramatic Theater, which heavily focused on aesthetics, and The Studio, an experimental theater formed by previous actors of Moscow Art Theater. One point I continue to struggle with is if this period (the avant-garde movement between 1907-1917) was more “Western” or less “Western” than before. On one hand, there were obvious efforts to distinguish Russian art and culture from Western Europe, but, on the other hand, there were also efforts to depart from the focus of Russian art being to reestablish Russia’s national identity. Also, while the Ballet Russes toured Europe and obviously established Russia as a unique, innovative art force, such contact with Western Europe must have also contributed to a “westernization” of Russia. As a result, I am unsure if Russia was more or less westernized in 1917, as the avant-garde period began to end and the war began. Also, if Russia was such a huge and vital force in establishing the culture of the early twentieth century, then what happened once the war began (and also once it ended)? How could this huge wave of artistry and creativity end so abruptly?

The Cultural Revival of Old Russia

The discussion of Russian popular culture and art in the early twentieth century is one heavily characterized by innovation, novelty, and experimentation. With the expansion of free speech seen in the advent of hundreds of newspapers and magazines, including the still famous Pravda, so too expanded the artistic venues by which painters, poets, composers, and actors plied their craft. In the closing years of the nineteenth century the Symbolists reigned supreme in Russian arts. Very much representative of traditional Russian culture, Symbolists followed a very hierarchal view of creative works, holding the artist as a “high priest,” affording him the right of interpretation and the ability to dictate the meaning and value of a work to the masses. Within a decade of the dawn of the 1900s, however, the revolutionary tendencies of popular politics took root in artistic movements, with new generations of poets and artists challenging tradition. The mysticism and almost religious veneration of old art was rejected in favor of concrete attention to the “real world.” New avant-garde artists Natalya Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov led the push to create a uniquely Russian medium for expression. Both created works evocative of the simple life, of country folk and the strong, old-fashioned tendencies they carry with them. This craving for a specific Russian culture, free of European influence, resulted in a resounding desire to flesh out and populate the movement with new works, a desire that saw Goncharova and Larionov illustrating poems written by their contemporaries, while poet Vladimir Mayakovsky set about setting peer paintings into poetic narratives. It is perhaps ironic that this desire to buck tradition led to such a saturation of work featuring folk life, popularly described as traditional. Igor Stravinsky’s 1913 ballet, Rite of Spring, was heavily influenced by Russian Primitivism, with the choreography filled with strong, decisive movements and powerful actions. Absent are the complex twirls, bounds, and poses that come to mind when one pictures ballet, replaced by almost tribal, ritualistic unified movements by crowds of strikingly costumed performers. Interestingly enough, Stravinsky is said to have denied the grounding of his compositions in traditional Russian folk music. Regardless of whether this claim holds truth, Stravinsky’s piece is evocative of traditional Russian peasant life, and ties in nicely with contemporary Russian neo-primitivistic works.

The Avant-Garde: Revolutionary Art

“Pictures of Pagan Russia in Two acts”-A fitting tagline for Igor Stravinsky and Vaslav Nijinsky’s ballet, Rite of Spring. Written and produced in 1913 during an artistic revolution in Russia, as well as Europe, Rite of Spring epitomizes the shift in artistic and political thought in Russia. The staccato rhythm of the music combined with the ritualistic, abrupt, and unstructured movements deviate from the traditional ballet performance centered around fluid scores and the graceful motions of the dancers. This departure from the classic ballet style with the depiction of an ancient pagan ritual reflects the revolutionary changes occurring in the arts, science, and philosophy with the emergence of the avant-garde.

In her book, Land of the Firebird, Suzanne Massie dedicates a chapter to discussing the evolution of the avant-garde in Russia. Emerging between 1908 and 1910, this new genre of art opposed the popular Symbolist movement that glorified hierarchy and the mystical world. Movements within the avant-garde instead sought to establish a new, modern art form that rejected the old world of art and placed its attention on the real world. This new artistic genre impacted all aspects of Russian creativity: poetry, painting, music, literature, and theater. One of the earlier styles to emerge during this period of artistic revolution was a new, neo-primitivism. The leading creator of this new Primitivism, artist Natalya Goncharova, gained her inspiration from popular lubki prints, the shapes of wooden dolls, and the folk art of the people. Not only did new Russian Primitivism influence other forms of art such as poetry and music, but it also reflected the shift in political and philosophical thought within Russia.

Following the romantic movement sweeping Europe during the nineteenth century, intellectuals and reformists in Russia at the turn of the twentieth century began to focus on the common people of Russia, the peasantry, and their customs in an effort to reform and revitalize Russia. The artistic movement away from the old world order, whether purposeful or not, is indicative of the social and political changes occurring in Russia. Starvinsky and Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring, being the most controversial contemporary example of the avant-garde movement, provides a strong example of this revolutionary genre.

Olga Rozanova

Olga Rozanova was born in 1886 in the province of Vladmir. She is known as a painter, poet, graphic designer, and illustrator.

From a young age she was trained in the arts, attending Bolshakov Art School and the Stroganov School of Applied Art in Moscow. In 1911 she moved to St. Petersburg where she attended the Zvantseva School of Art from 1912 to 1913. She became an active member of the Union of Youth Group, exhibiting with them regularly from 1911 to 1914.

In 1912 she met Russian Futurist poet Aleksey Kruchonykh and they began collaborating. Olga illustrated the first of his Futurist poetry books, which is how she was first exposed to the Futurist movement. They were married in 1916. She and her husband belonged to the group of Russian avant-guard artists called Supremus, and from there she collaborated with other colleagues. Supremus was intended to be a magazine about Suprematism, a style of art created by Kazimir Malevich, however no editions were ever published.

Her art started in the styles of neo-primitivism, Futurism and Cubism, but as she experimented it became more abstract, eventually morphing into a style all her own. She attended the lectures of the Italian Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in St Petersburg, which undoubtedly inspired some of her work. Shortly after meeting him, her work was shown at La Prima esposizione libera futurista internazionale in Rome.

Through her art she expressed her support for the Bolshevik Revolution. Following the revolution she became involved in social movements, such as the Proletarian Cultural Organisation.

She died in 1918 of diphtheria. She was 32 years old. After her death in 1918 a major exhibition was staged in her honor in Moscow.

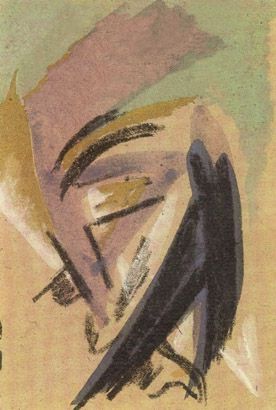

Illustration to the book of Kruchenykh Duck’s Nest.

Self portrait, painted in the neo-primitivist style.

To view more of her work, including illustrations for various poetry books, follow this link to her page at the Museum of Modern Art. Olga Rozanova–MOMA

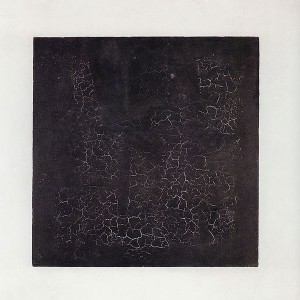

Malevich and the Avant-garde

Kazimir Malevich was an impressionist, pointillist, cubo-futurist, supremist, avant-garde painter, and patron of early avant-garde theater. His early career focused on the picturesque life of the peasantry, his primitivist works drew the attention of popular avant-gardist Mikhail Larionov. He invited Malevich to exhibit his works in the upcoming “Jack of Diamonds” show in Moscow. By 1910, Malevich had joined a number of art circles within Moscow including a pointillist group, an impressionist, and Larionov’s avant-garde group. After his appearance at “Jack of Diamonds”, in 1913, Malevich moved to Saint Petersburg and joined an avant-garde cell called the “Union of Youth”. Here, with the help of painters and futurist poets, he worked to produce futurist operas. By 1915 Malevich had entered a ‘suprematist’ period where he felt “Color and form are the only things that should matter for the painter: any painted surface is more vivid than a face with a pair of eyes and a smile on it.” This period led to the production of the famous series of “squares” and his suprematist work made him famous abroad and across Russia.

He would teach in Moscow for a time before dying St.Petersburg in 1935. Eventually, his grave was lost due to the rapid suburban expansion during and following the Second World War but his remains were rediscovered quite recently during construction in the area.

He would teach in Moscow for a time before dying St.Petersburg in 1935. Eventually, his grave was lost due to the rapid suburban expansion during and following the Second World War but his remains were rediscovered quite recently during construction in the area.

World of Art

Reading the Massie article assigned for today was particularly interesting for me because of the work I have been doing at my job in the college archives. A large number of books related to the World of Art movement were donated to the college by an alumni whose grandfather, Basil Troussoff, studied with Aleksander Benois, and worked as a painter and set designer in New York theater after he immigrated to the United States. The archives also hold a large amount of Basil’s personal papers, which I have been working on cataloging for the past year, culminating in an exhibit that will be on display very soon in the basement of the library.

Many of the books that were donated are exhibit catalogs from relatively unknown avant garde painters that whose work was displayed in Moscow in the from the late 19th century to the 1920’s. There are some by the more well-known painters as well, such as Aleksander Benois and Konstantin Somov. Many of the catalogs are also for exhibits of folk art from various regions of Russia. I originally thought this was a separate interest, but based on the focus of Russian roots and Russian identity in the principles of this movement, I now understand why Basil collected the books that he did. The archives also has an original copy of the publication World of Art, which showcased much of the work produced by members of the movement.

What I find especially interesting is that even though Basil was not participating in the same place as the center of the World of Art movement and even somewhat later, he still practiced the principals important to the movement, such as collaboration. Though he exhibited his own paintings, he focused on set design. Though he wasn’t working on such controversial pieces as the Rite of Spring, he helped to design sets in the studio of Joseph Urban, for performances by the Ziegfeld Follies and the Metropolitan Opera, important organizations in American theatre history.