Blog Post 9/13/2016

Carl Marquis-Olson

We Grow Out of Iron and The Ion Messiah

Gastev’s poem and his background represent a modernizing Russia. Gastev was a factory work, a member of the proletariat which was the fastest growing class of people and the new face of Russia in the early 20th century. He was a peasant who became literate and politically active. His profession and class play an increasingly important role in Russian society and according to Marxists, his class occupies the most politically crucial role in the new socialist order. After all Gastev is a socialist.

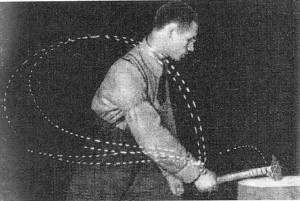

How do poems, specifically his poem, represent characteristics of modernity? The poem focuses largely on the material world. He describes the tools of industry: “workbenches, hammers, furnaces” etc. and the factory they are found in. He personifies the factory, growing taller and stronger as “fresh iron blood pours into my veins”. The very fact that he describes a factory, a productive enterprise made to produce materials, is evidence enough of this theme of materialism and in this way represents this characteristic of modernity. The poem concerns itself solely within the realm of man and machine. It captures the idea of progress and the changing world, it’s inevitability as the factory shouts “Victory shall be ours!”

Kirillov’s poem and Kirillov’s orgins are similar to Gastev’s. However, instead of celebrating the factory he celebrates the proletariat with his poem. He equates the common factory worker to god. He says “There he is – the savior, the lord of the earth. / The master of titanic forces… We thought he would appear in a sunlight stole, / With a nimbus of divine mystery,” His atheistic ode to humankind’s central place in the universe represents the humanism, secularism and scientific thought of modernity. He portrays the working man as the prophet, drawing a parallel with Christ’s central role in deliverance and the saving of humanity. Instead of god saving mankind it is man who will free and deliver the people of the world. This theme of nihilism and humankind’s supreme preeminence relates to this very secular aspect of modernity.