Art and culture seems to have been parallel with the greatest of the political philosophy Russia was seeing at the time. Russia had already begun to emerge a little bit on the international stage, but not enough. These artists wanted to explode this emergence and make the Russian art known throughout the world. This puts an emphasis on each individual in their part of the whole. Revolutionaries wanted to remake the world and believed that they could this new world into one in which things are unified. The poems “We Grow out of Iron”, “The War of Kings”, “The Iron Messiah”, and “We” all abound with metal imagery. This can be interpreted as symbolic of the development (or creation) of the new communist man. The symbolism of “Soviet metal” explores both the political and artistic revolutions that were taking place, as well as their common sentiment and objective of unification. The imagery of metal gives the reader a sense of how much the mass industrialization taking place at the time influenced the attitude of hope and power felt by both artistic and political revolutionaries. The workers were the revolutionaries; they were hardened (or “steeled”) to the heavy metal and machinery of their trades, and unified via this harsh labor. Aleksei Gastev in fact, author of “We Grow Out of Iron”, worked in Russian and European factories and his experiences as a laborer steered him toward Marxism. Revolution for Gastev endeavored to enable workers by sanctioning them power over day-to-day work related practices. Gastev was also involved in the efforts of the Petersburg Union of Metal Workers. His poetry powerfully exults in industrialization; declaring it an era of an innovative form of man, qualified by the total modernization of his routine existence as a laborer.

Tag Archives: we grow out of iron

“Chapaev” and “We Grow Out of Iron”: Industrialization and Revolutionary Thoughts

In both “Chapaev” and “We Grow Out of Iron”, the authors are teaching the audience about industrialism and revolutionary thoughts. After the revolution in 1917, new thoughts on modernity emerged.

In Gastev’s poem, “We Grow Out of Iron”, symbols of factories and iron structures elude to society changes, both literal and metaphorically. Gastev describes the buildings are very large and indestructible. The author also describes them as ever-growing structures. After the revolution of 1917, new definitions of modernity emerged. Technology and industrialization became much more ominous. Gatev hints at this in the poem, “they demand yet greater strength”. Not only are the building actually growing taller, they are growing more powerful.

The poem also mentions the factory workers’ role in this emerging industrialization. As the factories grow stronger, so do the workers. They are taking on more tasks and their importance in industry is ever growing. With greater responsibility comes the workers’ feeling of inhumanity. The poem says, “My feet remain on the ground, but my head is above the building.” The author is teaching the audience the importance of factory workers in industry and modernity. The works have become “one with the building’s iron.” The revolution, as illustrated in “Chapaev”, is all about the congregation and rise of the working class.

Gastev’s Soviet Unions

Though the poet Aleksei Gastev was killed during Stalin’s Great Purges, he had been a Communist supporter for much of his life. Though he was distanced from the Party in 1907, when he was in his late twenties, after a disagreement on how to combat the spread of capitalism, he still supported the proletariat in a variety of ways. Gastev’s intention in “We Grow out of Iron” can be better understood if we consider his strong belief in unions, which was the basis of his break from the Party.

The use of strong “pro-labor” phrasing in this piece could be easily interpreted as contributing to an early piece in the Socialist-realism movement, not fully popular until the 1930s. The way he glorifies progress also seems to allude to his socialist tendencies.

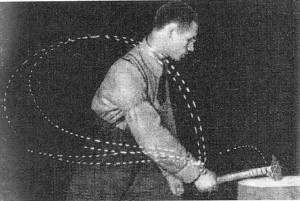

Of particular interest in this piece is Gastev’s use of personal pronouns. The poem separates the narrator form other characters in the piece through its use of “I’ and “They”. One of the conflicts in this poem comes from the narrators interaction with the building, with the “they”. This “iron structure” (ln. 6) is given qualities associated with the early Soviet movement in the USSR– “They are bold, they are strong./ They demand yet greater strength.” (Ln. 7-8). This piece is Gastev’s argument for the future of the Communist state. He believes that through unionization of the proletariat they can organize labor for themselves better than a distanced administration. The unions, Gastev assrets, can “[force] the rafters, the upper beams, the roof…higher.” (ln. 14-19), that they could have propelled the Soviet Union forward. But, the labor would have had to be organized by the workers, by these groups grown out of the population. This is most evidenced by the Gastev’s opening line, “I stand among workbenches, hammers, furnaces, forges, and among a hundred comrades.”

Revolutionary Thought in Russian Literature

To me, the poem “We Grow Out of Iron” by Aleksei Gastev is about the power of the working class of Russia. The poem begins with the subject constructing a building out of iron, but by the middle lines of the poem the subject realizes that his work makes him strong, too. He grows confident and solid in his actions, surprising himself with his own strength and endurance as he shouts to his comrades “may I have the floor?” This echoes the revolution in the early 20th Century, when the wives and mothers began rioting over lack of food and, backed by their factory-working husbands and children, started a movement that would lead to significant change. What started as a demand for food turned into something stronger, the impact of which no one expected. When the workers all banded together the inertia of their actions was too strong to stop and before they knew it, they had made a real change—victory was theirs.

In contrast, I see in chapter five in Chapaev by Dmitri Furmanov the other approach to revolution that emphasizes educated leaders as the way to reform. Klychkov, the character based off the author Furmanov, is clearly educated, distinguishing himself from the famous Chapaev. Klychkov is also a plotter, carefully detailing how he plans on proving himself worthy to Chapaev and gain his confidence and trust. He does this because he believes that Chapaev, despite being uneducated, could be a true revolutionary because of his peasant origins, which is where the “spontaneous feelings of rage and protest” grow strong. He recognizes this phenomenon among the peasantry, but at the same time questions, “who can see what spontaneous protest will lead to?” (Furmanov, 63). He is weary of the efficacy of a wide revolt, wondering if uneducated peasants can actually bring about the change that is so necessary.

The famous Vasily Chapaev of the Russian Civil War.