I am running all of my ongoing intermediate Latin and Greek classes on the basis of sight reading, rather than the traditional prepared translation method, and using elements of the flipped class concept with video content made with the ShowMe app. The concept is described in an APA paper I gave this year, and some of the nuts and bolts of the system, such as it is, are described in an earlier post. So how is it going, you ask? I’m doing a lot of grading (and avoiding it right now), but I am just thrilled at the change in the classroom dynamics and ethos.

Probably the best day was the day we worked on the basics of Latin scansion and metrics in the Catullus class (4th semester). They watched my little videos about the basics, material I used to do as lecture, but is now available in video form. Then in class we scanned Catullus 1 together: after the briefest of reviews (2 mins. at most) I let them loose on a big photocopy of Cat. 1 with lots of space between the lines, and off they went in pairs. A few had fully absorbed the difference between a long vowel and a long syllable, the concept of elision, and so forth, but many had not. I was able to hover around and give tips and little mini explanations using the examples at hand in a way that had everybody on the boat by the end of 30 minutes. I then projected the poem on to the blackboard and scanned it with them, just to check that everybody had it right. Class over, skill acquired, one hour, and they seemed to actually enjoy it. This is something I never was able to teach properly, and burned hours of class time tying futilely to explain in the abstract. This is a perfect application to Latin of the flipped class concept, lecture material outside of class, project-based collaboration inside. Bingo.

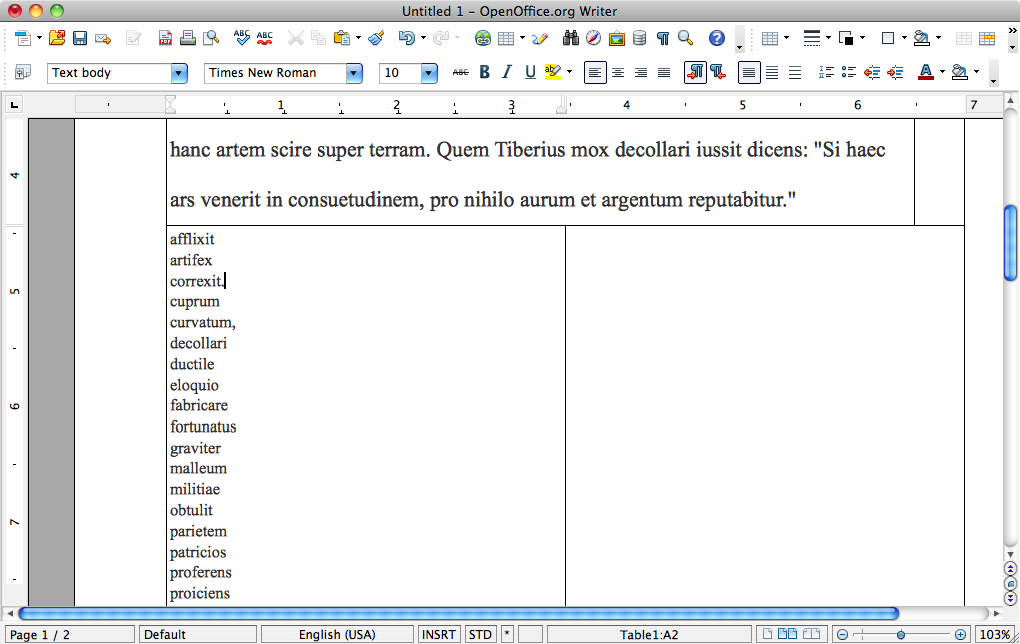

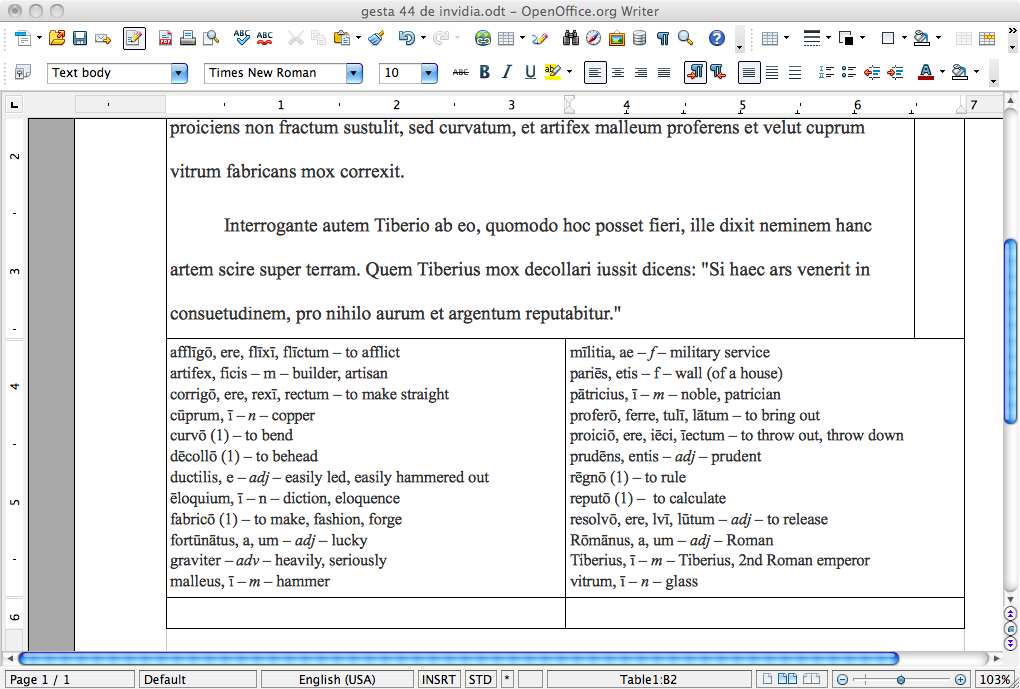

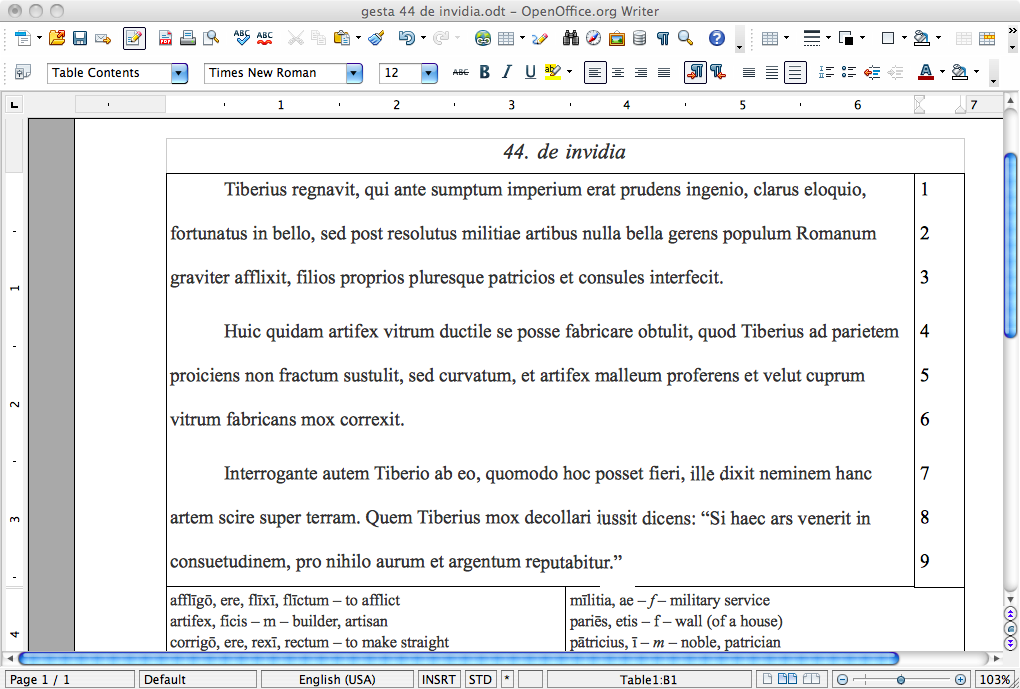

When it come to translation, things are a bit more complicated. I’m relying on them to absorb a vocabulary list for the day’s passage, then we translate together. Sometimes I call on individuals, sometimes I ask for volunteers. This is actually working quite well for the most part. The level of attention and focus on endings and word order is completely new, a total change from what we are all familiar with in the traditional method, where endings are seen as an annoying afterthought, word order as a kind of puzzle, Latin as mixed-up English. We go through word by word first, analyzing the endings (this often leads to mini-reviews on the board of, say, the reflexive pronoun). A second pass yields more or less decent English. We tend to re-translate the passage the next day as review, something necessary when sight-reading in my view.

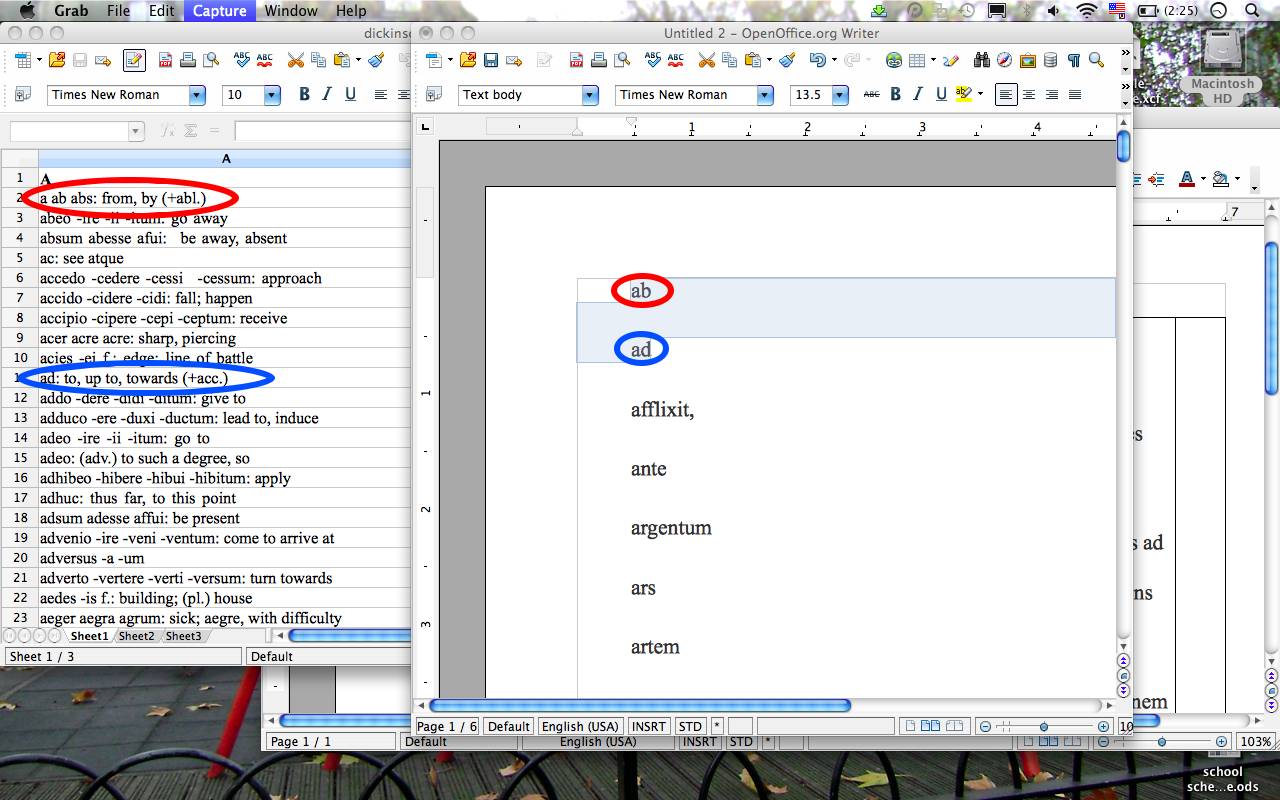

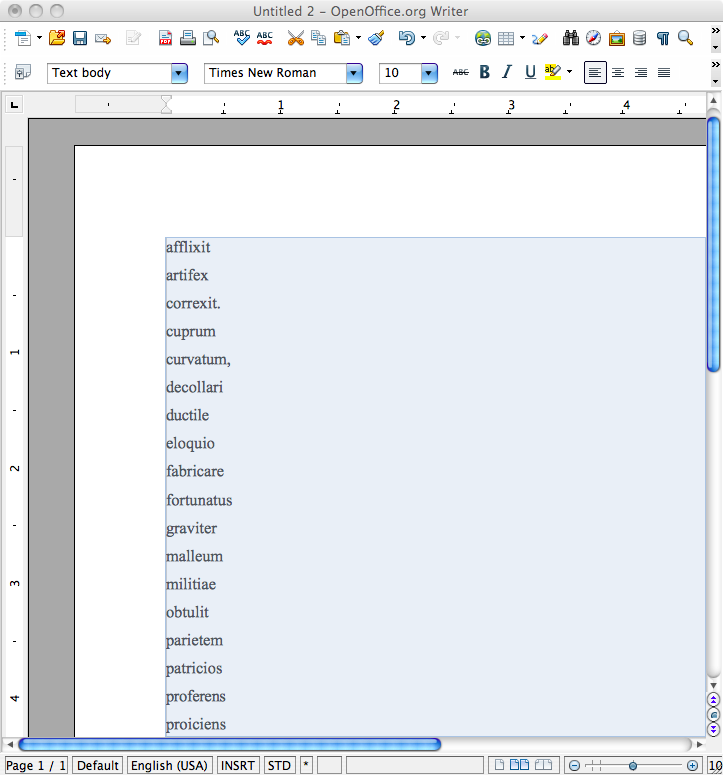

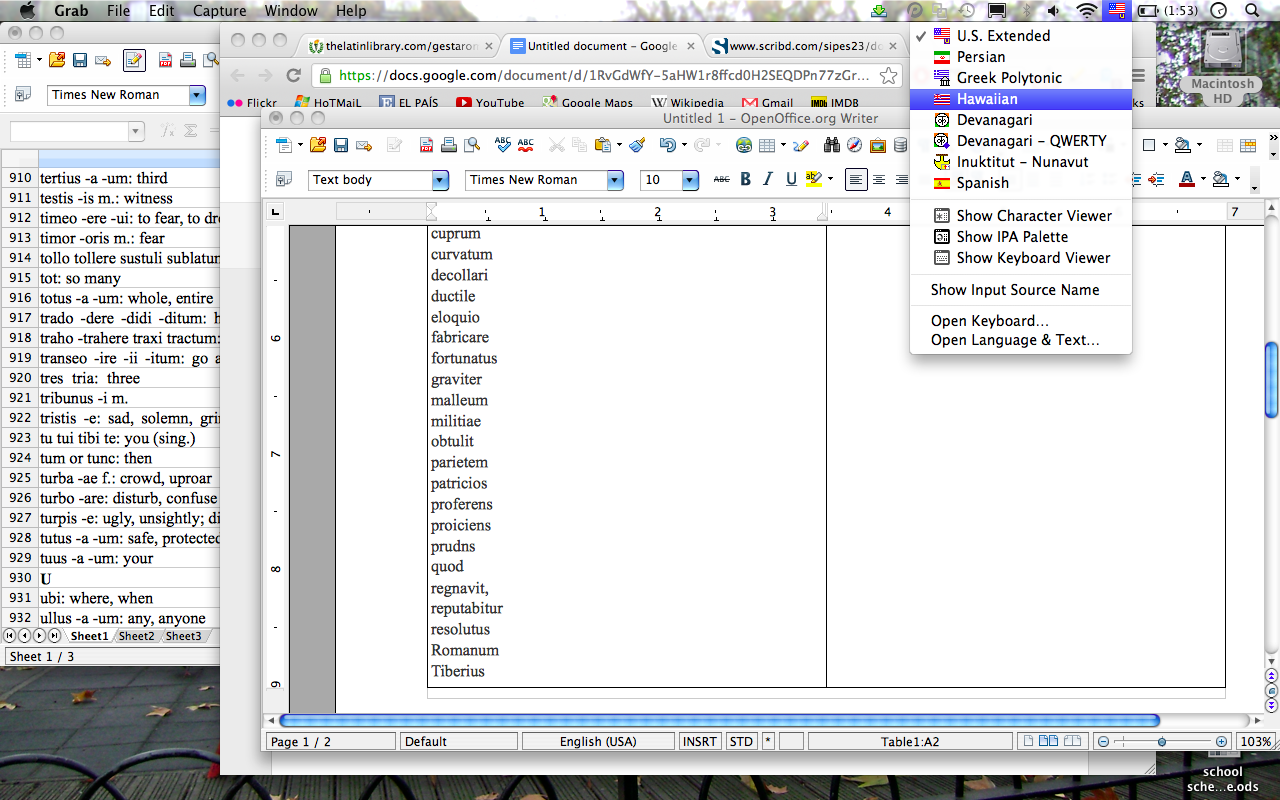

The rub comes when they say “I don’t know what that word means,” though they were supposed to have learned the list the night before. Not that this is a crippling problem so far, but it brings up the perennial quandary of how to get students to efficiently absorb vocabulary.

My new inspiration for vocabulary work (this being in place of the usually unsuccessful attempt to translate at home, which is characteristic of the traditional method), is something I call vocabulary dots. Given a list of 20-30 lemmas, students choose three activities that simultaneously get them to use the words on the list and help them gain active command of key grammatical structures we will see in the texts themselves. Here are the dots. Let me know if you have any thoughts or comments! I have nicer formatting, with little sphinx emblems (these are the “dots,” but it’s not coming through in WordPress. The not terribly logical term “dots,” by the way, has caught right on, and all the students use it as an easy shorthand for loathsome term “activities,” which I suppose is more accurate. In the syllabus I just say “vocab. dots for Catullus 5 and 6” and they get the picture.

Latin Vocabulary Activities

For a new list of words, choose three activities. They should take about twenty minutes each.

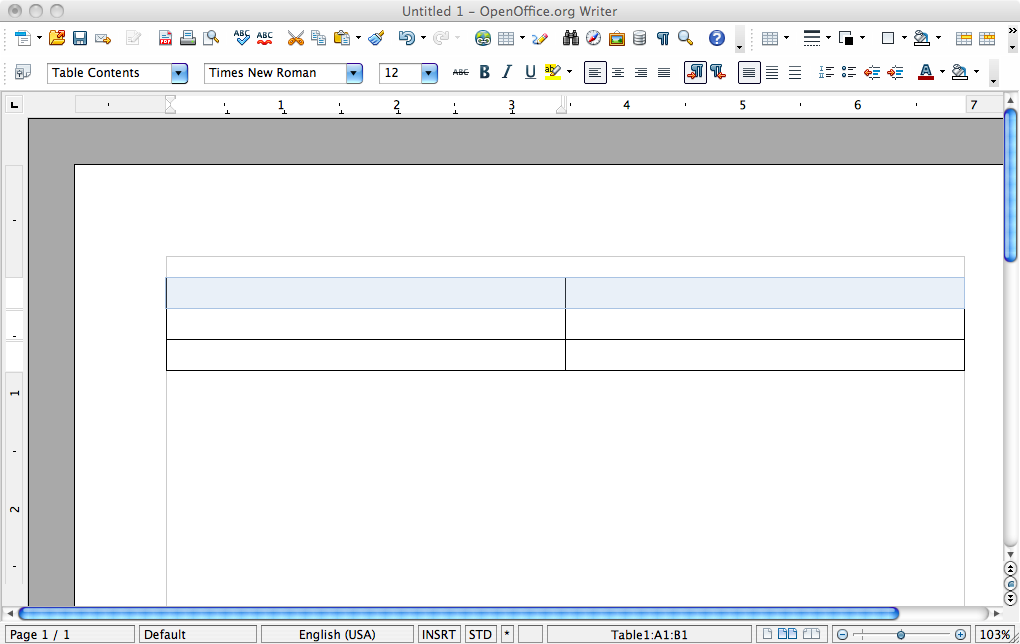

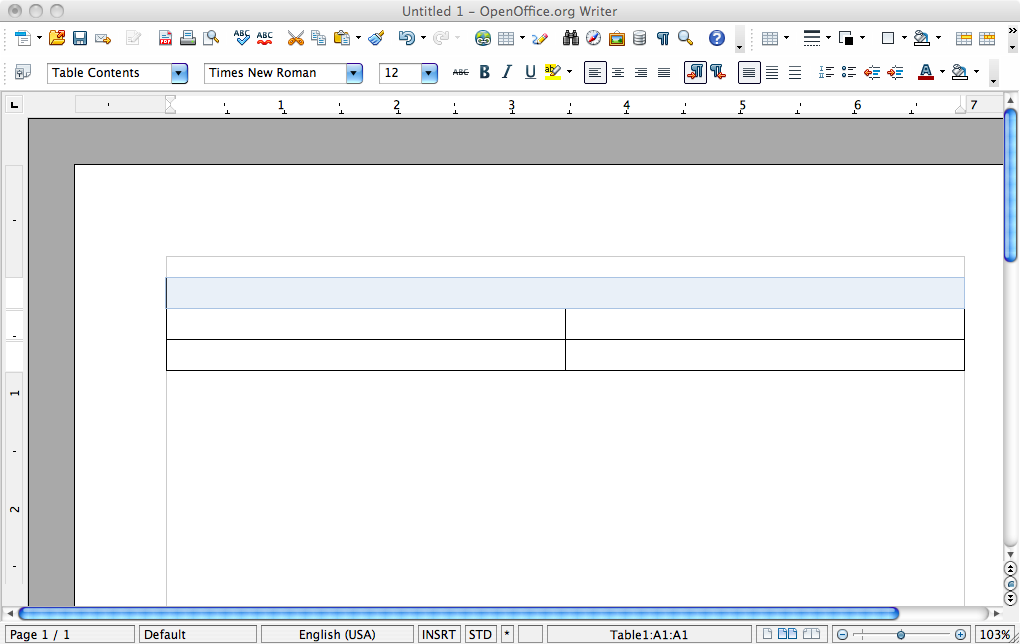

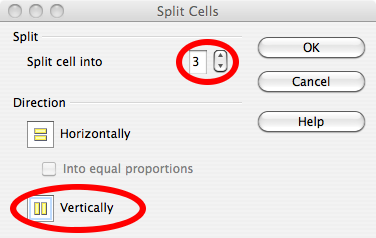

| I’d Have To Agree:Create fifteen noun-adjective pairs (e.g. manūs dextrae, right hands, fem. nom. pl.). Use all numbers, cases, and genders once. Translate the resulting combinations. | MiniSynopsis:Pick 6 verbs and give either a) all 6 tenses of the indicative in one person and number, b) all 4 tenses of the subjunctive in one person and number, c) all four participles, or d) all five infinitives. Make sure to use all options at least once, and a mix of active and passive voice. If there are fewer than six verbs, re-use. | Absolutely Ablative:Create ten ablative absolutes (including participle and noun), using a combination of as many words as possible. Make five passive and five active, and translate the results. |

| The Word Next Door:Write out 15 words with an etymologically related Latin word in the dictionary. Give full dictionary form and short definitions for each. E.g.: manus -ūs f. hand, band; manualis -e (adj.) for the hand. | Meet the Relatives:Write five short sentences using the given vocabulary words, including a relative clause in each. Make sure the relative pronoun is in the right gender, number, and case. Use five different combinations of gender, number, and case. Translate the results. | Acting Up: Write five short sentences including transitive verbs in the active voice, with a direct object. Reverse them so that the verb is passive, and the direct object the new subject. Make sure to change the endings accordingly, and translate both versions. |

Greek Vocabulary Activities

For a new list of words, choose three activities. They should take about twenty minutes each.

| I’d Have To Agree:Create five article-adjective-noun sets (e.g. τοῖς καλοῖς ἀνδράσι, for the handsome men, m. pl. dat.). Use as many different words as possible, and different combinations of number, case, and gender each time. Translate the resulting combinations.

|

MiniSynopsis:Pick six verbs and give one conjugated form for each principal part listed in Pharr’s lexicon. Use all combinations of person and number once. | Daring Do: Create five combinations of participle and finite verb (e.g. εἰπών ἕζετο, “having spoken he sat down”). Use as many different verbs as possible. Use a variety of tenses, genders, and numbers, and make sure that the participle (which will always be in the nominative) agrees with the verb in number.

|

| The Word Next Door: write out 15 words words with an etymologically related Greek word in the dictionary. Give full dictionary form and short definitions for each. E.g.: ἥλιος -ου, ὁ sun; ἡλιόομαι be exposed to the sun). You may want to use LSJ for this. Make sure the words are in fact etymologically related, and not just spelled similarly | Meet the Relatives: write five short sentences using the given vocabulary words, including a relative clause in each. Make sure the relative pronoun is in the right gender, number, and case. Use five different combinations of gender, number, and case. Translate the results. | In That Case:Take ten nouns, pair them with ten different prepositions, and translate the result. Make sure that the noun is in an appropriate case for that preposition, and if the preposition can take more than one case make sure it is translated according to the case you use. |

–Chris Francese

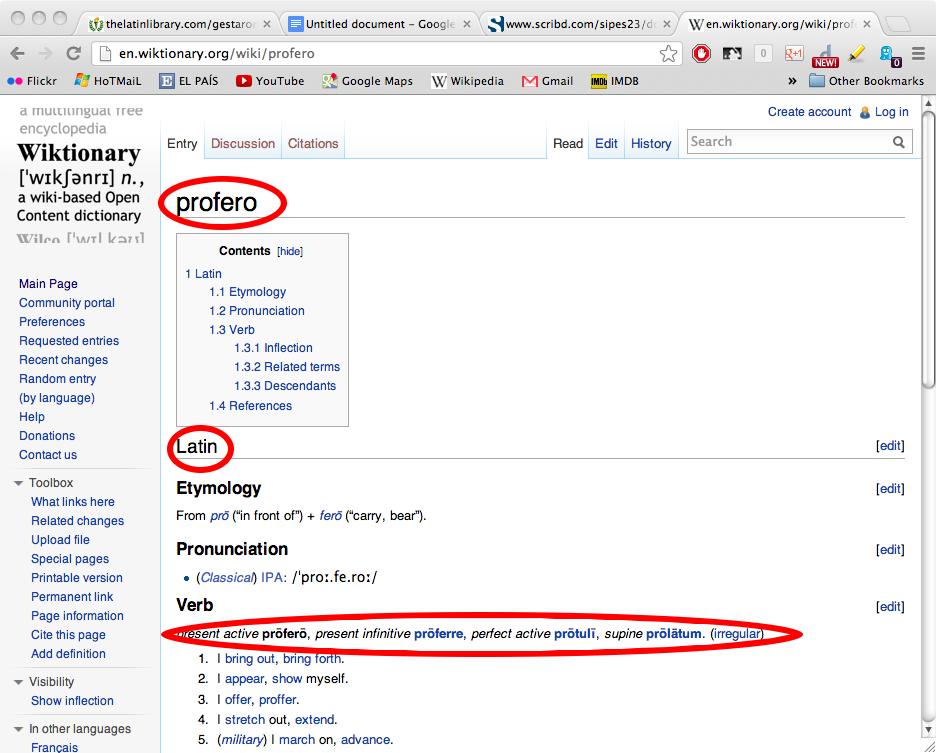

The idea behind principal parts is to put in your hands, and hopefully in your brain, all the different stems of a verb, so that (theoretically) any declined form can be derived from, or traced back to, one of them. But of course it’s not quite that simple.

The idea behind principal parts is to put in your hands, and hopefully in your brain, all the different stems of a verb, so that (theoretically) any declined form can be derived from, or traced back to, one of them. But of course it’s not quite that simple.