Dickinson Summer Latin Workshop: July 11-15, 2022

Moderators: Prof. Chris Francese and Dr. Meghan Reedy

The Dickinson Summer Latin Workshop will be held online this year. While this situation is far from ideal, we hope it will allow those who could not normally travel to Carlisle to participate.

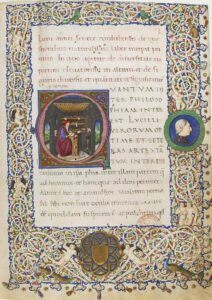

First page of the manuscript De questionibus Naturalibus, made for the Catalan-Aragonese crown. Image: Wikipedia (Public Domain)

This year’s text is one seldom read these days, the Naturales Quaestiones of Seneca the Younger. This prose work concerns natural phenomena (rivers, earthquakes, wind, snow, meteors, and comets). It gives fascinating insights into ancient philosophical and scientific approaches to the physical world, and also vivid evocations of the grandeur, beauty, and terror of nature. Seneca also comments on aspects of Roman culture, such as the commercial trade in snow and the decadent (in his view) use of mirrors. The selections we will read are from a forthcoming Dickinson College Commentaries edition of selections from NQ edited by Prof. Chris Trinacty of Oberlin College. Participants will have pre-publication access to Chris’s detailed notes and vocabulary lists.

We are delighted to welcome back Dr. Meghan Reedy as guest instructor. She is a former Dickinson faculty member and is currently Program Coordinator with the Maine Humanities Council.

Meetings

- Online meetings will take place daily 1:00 p.m. to 4:30, Eastern time US, with a break in the middle. Group translation will be carried on in two sections, one for the more confident (affectionately known as “the sharks”), one for the less confident (even more affectionately known as “the dolphins”) led on alternating days by Reedy and Francese.

Reading Schedule (projected)

Monday, July 11: NQ 3 pref. 1-4, 3.15.1-8, 3.30-1-8

Tuesday, July 12: NQ 4a.2.12-15, 4b.13.1-11, 5.13.1-15.4

Wednesday, July 13: NQ 6.3.1-6.5.3, 6.8.1-6.10.2, 7.28.1-7.30.6

Thursday, July 14: NQ 1.pref. 5-13, 1.13.1-14.6, 1.17.1-10

Friday, July 15: NQ 2.36.1-38.4, 2.59.1-13.

Registration Fee

$200, due by check on or before July 1, 2022. Make checks payable to Dickinson College and mail them to

Department of Classical Studies, Dickinson College

c/o Stephanie Dyson

Carlisle, PA 17013