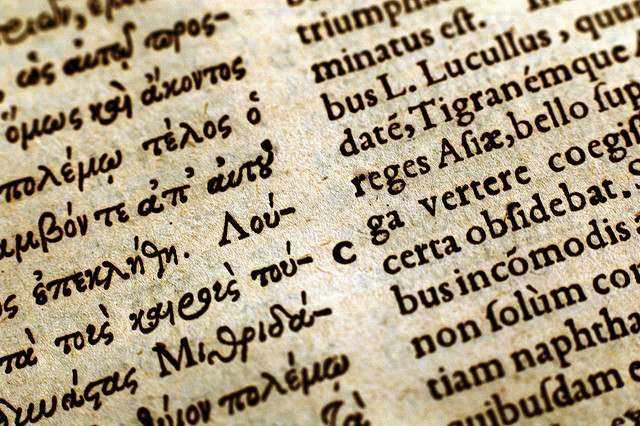

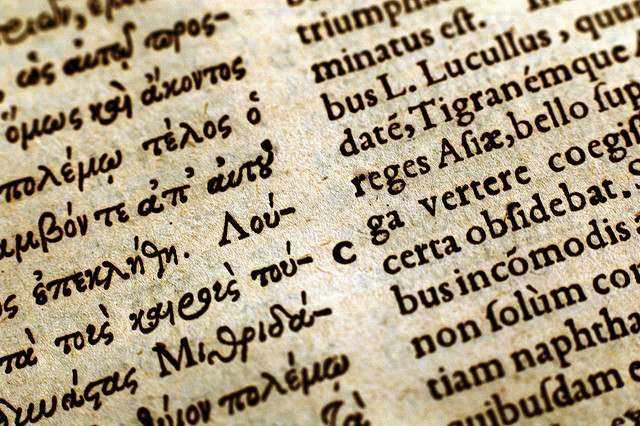

Crytian Cruz, via Flickr (http://bit.ly/13HaBAU)

(This is a slightly revised version of a talk given by Chris Francese on January 4, 2013 at the American Philological Association Meeting, at the panel “New Adventures in Greek Pedagogy,” organized by Willie Major.)

Not long ago, in the process of making some websites of reading texts with commentary on classical authors, I became interested in high-frequency vocabulary for ancient Greek. The idea was straightforward: define a core list of high frequency words that would not be glossed in running vocabulary lists to accompany texts designed for fluid reading. I was fortunate to be given a set of frequency data from the TLG by Maria Pantelia, with the sample restricted to authors up to AD 200, in order to avoid distortions introduced church fathers and Byzantine texts. So I thought I had it made. But I soon found myself in a quicksand, slowly drowning in a morass infested with hidden, nasty predators, until Willie Major threw me a rope, first via his published work on this subject, and then with his collaboration in creating what is now a finished core list of around 500 words, available free online. I want to thank Willie for his generosity, his collegiality, his dedication, and for including me on this panel. I also received very generous help, data infusions, and advice on our core list from Helma Dik at the University of Chicago, for which I am most grateful.

What our websites offer that is new, I believe, is the combination of a statistically-based yet lovingly hand-crafted core vocabulary, along with handmade glosses for non-core words. The idea is to facilitate smooth reading for non-specialist readers at any level, in the tradition of the Bryn Mawr Commentaries, but with media—sound recordings, images, etc. Bells and whistles aside, however, how do you get students to actually absorb and master the core list? Rachel Clark has published an interesting paper on this problem at the introductory level of ancient Greek that I commend to you. There is also of course a large literature on vocabulary acquisition in modern languages, which I am going to ignore completely. This paper is more in the way of an interim report from the field about what my colleague Meghan Reedy and I have been doing at Dickinson to integrate core vocabulary with a regime based on sight reading and comprehension, as opposed to the traditional prepared translation method. Consider this a provisional attempt to think through a pedagogy to go with the websites. I should also mention that we make no great claim to originality, and have taken inspiration from some late nineteenth century teachers who used sight reading, in particular Edwin Post.

In the course of some mandated assessment activities it became clear that the traditional prepared translation method was not yielding students who could pick their way through a new chunk of Greek with sufficient vocabulary help, which is our ultimate goal. With this learning goal in mind we tried to back-design a system that would yield the desired result, and have developed a new routine based around the twin ideas of core vocabulary and sight reading. Students are held responsible for the core list, and they read and are tested at sight, with the stipulation that non-core words will be glossed. I have no statistics to prove that our current regime is superior to the old way, but I do know it has changed substantially the dynamics of our intermediate classes, I believe for the better.

Students’ class preparation consists of a mix of vocabulary memorization for passages to be read at sight in class the next day, and comprehension/grammar worksheets on other passages (ones not normally dealt with in class). Class itself consists mainly of sight translation, and review and discussion of previously read passages, with grammar review as needed. Testing consists of sight passages with comprehension and grammar questions (like the worksheets), and vocabulary quizzes. Written assignments focus on textual analysis as well as literal and polished literary translation.

The concept (not always executed with 100% effectiveness, I hasten to add) is that for homework students focus on relatively straightforward tasks they can successfully complete (the vocabulary preparation and the worksheets). This preserves class time for the much more difficult and higher-order task of translation, where they need to be able to collaborate with each other, and where we’re there to help them—point out word groups and head off various types of frustration. It’s a version, in other words, of the flipped classroom approach, a model of instruction associated with math and science, where students watch recorded lectures for homework and complete their assignments, labs, and tests in class. More complex, higher-order tasks are completed in class, more routine, more passive ones, outside.

There are many possible variations of this idea, but the central selling point for me is that it changes the set of implicit bargains and imperatives that underlie ancient language instruction, at least as we were practicing it. Consider first vocabulary: in the old regime we said essentially: “know for the short-term every word in each text we read. I will ask you anything.” In the new regime we say, “know for the long-term the most important words. The rest will be glossed.” When it comes to reading, we used to say or imply, “understand for the test every nuance of the texts we covered in class. I will ask you any detail.” In the new system we say, “learn the skills to read any new text you come across. I will ask for the main points only, and give you clues.” What about morphology? The stated message was, “You should know all your declensions and conjugations.” The unspoken corollary was “But if you can translate the prepared passage without all that you will still pass.” With the new method, the daily lived reality is, “If you don’t know what endings mean you will be completely in the dark as to how these words are related.” When it comes to grammar and syntax, the old routine assumed they should know all the major constructions as abstract principles, but with the tacit understanding that this is not really likely to be possible at the intermediate level. The new method says, “practice recognizing and identifying the most common grammatical patterns that actually occur in the readings. Unusual things will be glossed.” More broadly, the underlying incentives of our usual testing routines was always, “Learn and English translation of assigned texts and you’ll be in pretty good shape.” This has now changed to: “know core vocabulary and common grammar cold and you’ll be in pretty good shape.”

Now, every system has its pros and cons. The cons here might be a) that students don’t spend quite as much time reading the dictionary as before, so their vocabulary knowledge is not as broad or deep as it should be; b) that the level of attention to specific texts is not as high as in the traditional method; and c) that not as much material can be covered when class work done at sight. The first of these (not enough dictionary time) is a real problem in my view that makes this method not really suitable at the upper levels. At the intermediate level the kind of close reading that we classicists value so much can be accomplished through repeated exposure in class to texts initially encountered at sight, and through written assignments and analytical papers. The problem of coverage is alleviated somewhat by the fact that students encounter as much or more in the original language than before, thanks to the comprehension worksheets, which cover a whole separate set of material.

On the pro side, the students seem to like it. Certainly their relationship to grammar is transformed. They suddenly become rather curious about grammatical structures that will help them figure out what the heck is going on. With the comprehension worksheets the assumption is that the text makes some kind of sense, rather than what used to be the default assumption, that it’s Greek, so it’s not really supposed to make that much sense anyway. While the students are still mastering the core vocabulary, one can divide the vocabulary of a passage into core and non-core items, holding the students responsible only for core items. Students obviously like this kind of triage, since it helps them focus their effort in a way they acknowledge and accept as rational. The key advantage to a statistically based core list in my view is really a rhetorical one. In helps generate buy-in. The problem is that we don’t read enough to really master the core contextually in the third semester. Coordinating the core with what happens to occur in the passages we happen to read is the chief difficulty of this method. I would argue, however, that even if you can’t teach them the whole core contextually, the effort to do so crucially changes the student’s attitude to vocabulary acquisition, from “how can I possibly ever learn this vast quantity of ridiculous words?” to “Ok, some of these are more important than others, and I have a realistic numerical goal to achieve.” The core is a possible dream, something that cannot always be said of the learning goals implicit in the traditional prepared translation method at the intermediate level.

The question of how technology can make all this work better is an interesting one. Prof. Major recently published an important article in CO that addresses this issue. In my view we need a vocabulary app that focuses on the DCC core, and I want to try to develop that. We need a video Greek grammar along the lines of Khan Academy that will allow students to absorb complex grammatical concepts by repeated viewings at home, with many, many examples, annotated with chalk and talk by a competent instructor. And we need more texts that are equipped with handmade vocabulary lists that exclude core items, both to facilitate reading and to preserve the incentive to master the core. And this is where our project hopes to make a contribution. Thank you very much, and I look forward to the discussion period.

–Chris Francese

HANDOUT:

Greek Core Vocabulary Acquisition: A Sight Reading Approach

American Philological Association, Seattle, WA

Friday January 4, 2013

Panel: New Adventures in Greek Pedagogy

Christopher Francese, Professor of Classical Studies, Dickinson College francese@dickinson.edu

References

Dickinson College Commentaries: http://dcc.dickinson.edu/

Latin and Greek texts for reading, with explanatory notes, vocabulary, and graphic, video, and audio elements. Greek texts forthcoming: Callimachus, Aetia (ed. Susan Stephens); Lucian, True History (ed. Stephen Nimis and Evan Hayes).

DCC Core Ancient Greek Vocabulary http://dcc.dickinson.edu/vocab/greek-alphabetical

About 500 of the most common words in ancient Greek, the lemmas that generate approximately 65% of the word forms in a typical Greek text. Created in the summer of 2012 by Christopher Francese and collaborators, using two sets of data: 1. A subset of the comprehensive Thesaurus Linguae Graecae database, including all texts in the database up to AD 200, a total of 20.003 million words (of which the period AD 100–200 accounts for 10.235 million). 2. The corpus of Greek authors at Perseus Chicago, which at the time our list was developed was approximately 5 million words.

Rachel Clark, “The 80% Rule: Greek Vocabulary in Popular Textbooks,” Teaching Classical Languages 1.1 (2009), 67–108.

Wilfred E. Major, “Teaching and Testing Classical Greek in a Digital World,” Classical Outlook 89.2 (2012), 36–39.

Wilfred E. Major, “It’s Not the Size, It’s the Frequency: The Value of Using a Core Vocabulary in Beginning and Intermediate Greek” CPL Online 4.1 (2008), 1–24. http://www.camws.org/cpl/cplonline/files/Majorcplonline.pdf

Read Iliad 1.266-291, then answer the following in English, giving the exact Greek that is the basis of your answer:

- (lines 266-273) Who did Nestor fight against, and why did he go?

who

why

- (lines 274-279 ) Why should Achilles defer to Agamemnon, in Nestor’s view?

- (lines 280-284) What is the meaning and difference between κάρτερος and φέρτερος as Nestor explains it?

- (lines 285-291) What four things does Achilles want, according to Agamemnon?

Find five prepositional phrases, write them out and translate, noting the line number, and the case that each preposition takes.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Find five verbs in the imperative mood, write them out and translate, noting the line number and tense of each.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.