This week a new project for DCC begins, the digitization and editing of A Greek Reader by Charles Anthon (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1840, with editions up through 1854). This work is itself a selection and reworking of Frederic Jacob’s 4-volume behemoth, Elementarbuch der griechischen Sprache für Anfänger und Geübtere, published in many editions in the early nineteenth century. If you believe the long, hostile, and anonymous review in the Boston-based North American Review of 1840, Anthon largely plagiarized his selection and translation of Jacobs from the 1832 Boston edition by Hilliard and Gray. But this is unfair. Anthon’s notes are new and extensive, and very useful to beginners. The review eventually admits this, but then roasts Anthon for giving too much help in the notes, a flaw that will, it asserts, utterly destroy standards of scholarship in the United States. Student friendly, this Anthon, my kind of guy. Stephen Newmeyer’s appreciation in Classical Outlook 59.2 (1981-82), pp. 41-44, gives a good summary of his remarkable career at Columbia College.

Team Anthon as of May 23, 2023: Scott Smith, Chris Francese, Nick Morris, Haydon Alexander, Ryan Saputo, Jillienne Robinson-Warren, Mandy Porter, Barry Brinker, Meagan Ayer. Not pictured: Keziah Armstrong.

The book contains two “courses.” The shorter first course contains brief sentences exemplifying specific morphological features, such as declensions or conjugations. The longer second course consists of short to medium-length passages thematically arranged: Aesopic fables, anecdotes of philosophers, anecdotes of kings and statesmen, and anecdotes of Spartans. There is a section “natural history” (i.e. interesting critters), a section of mythology, mythological narrations, mythological dialogues (from Lucian), and a long section on geography. Then there is a series of extracts from Plutarch (“History and Biography”) mostly about Athenian statesman. There follow several poetic extracts from Homer and Anacreon, among others.

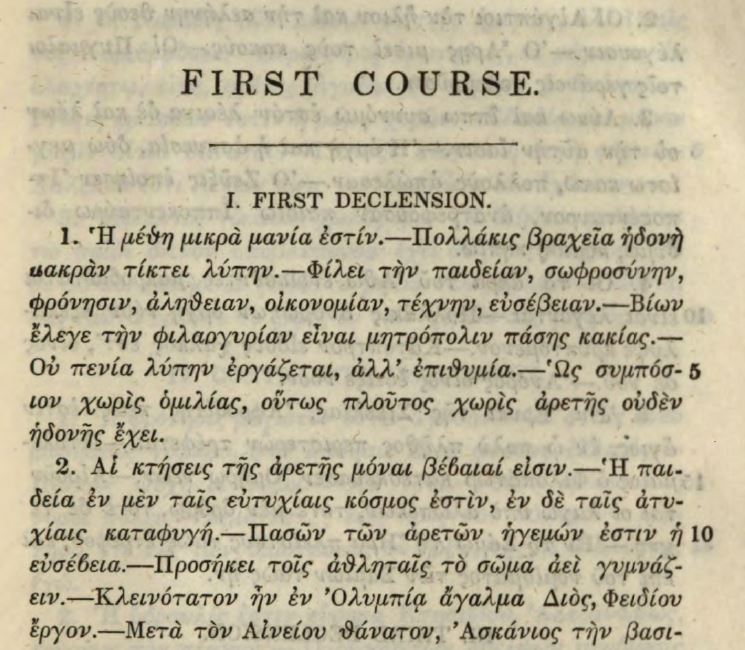

The “First Course” gives short sentences which drill a particular declension or conjugation.

Our merry band of students, professors and other volunteers intends to digitize most of the work this summer using Bruce Robertson’s web-based application Lace: Visualizing, Editing and Searching Polylingual OCR Results. Once we have a digitized text we can begin editing and presenting the text with running vocabulary in DCC style. The current plan is to cut down somewhat on the geography section, which gets a bit dull, omit the Homer selections, since we already have a growing edition of Homer’s Odyssey on DCC, as well as Books 6 and 22 of the Iliad.

We plan to modernize the work by taking out some of the gendered language in the notes, and we will probably include extra passages that compensate for the reader’s masculine and Atheno-centric biases, which go back to Jacobs. This is an old work, and a resurrected Anthon will certainly not suit the needs of every teacher or student. The goal is to put a large amount of relatively easy Greek in the hands of readers with full running vocabulary lists and links to our version of Goodell’s School Grammar of Attic Greek. We are collaborating also with the Greek Learner Texts Project led by James Tauber and connected with Perseus. This will hopefully go part way to rectifying the imbalance between the sorts of lower intermediate resources available for Latin and the much smaller amount of such material available for Greek.

There are many such Greek readers from the 19th century, Greek Learner Texts Project is working on some of these. Our group consists of students from Dickinson, the University of New Hampshire, teachers, and some volunteers from the DCC community, all ably led by Professor R. Scott Smith from the University of New Hampshire. We’re very excited about this project. It’s a little different than what we have been publishing so far on DCC, but I trust that it will find a niche on our site. In the long term we could augment with other material from other Greek readers into a kind of super mega Greek reader. But for now we’re going to focus on Anthon, since his notes are so helpful for beginners. It will probably take a least a year to complete, more likely two, so if you would like to get involved in some way, please do let us know!