A paedagogus is assigned to the young so that the rowdiness of youth might be restrained and their hearts prone to sin be held in check . . . by the fear of punishment. (Jerome, Commentary on Paul’s Letter to the Galatians 2.3.24)

For he removed that area of philosophy which has to do with admonitions, and said that it was the business of the paedagogus, not the philosopher. As if the wise man is something other than a paedagogus for the human race. (Seneca, speaking of the philosopher Ariston of Chios, Letters 89.13.)

I will say this much further about paedagogi: that they should either be educated, which would be my preference, or else they should know that they are not educated. (Quintilian, On the Orator’s Education 1.1.8)

How she used to cling to her father’s embrace! How lovingly and modestly she used to hug us, her father’s friends! How she loved her nurses, her pedagogues, her teachers, each appropriately according to their roles! (Pliny the Younger, from a letter describing the death of a young girl, Letters 5.16.3.)

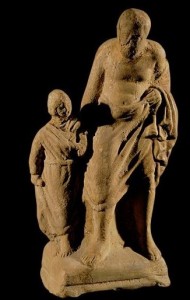

Well-to-do Roman children spent most of their time under the direct care not of their parents but of tutors, usually older and trusted male slaves, called often by the Greek term paedagogus (“child leader”). Other Latin terms exist: comes (“companion”) and custos (“guardian”). But the foreign word presumably sounded more elegant, much as in English an au pair sounds more sophisticated than a nanny or babysitter. The custom was so general by Augustus’s day that when that emperor was making regulations for theater seating, he assigned a section to boys (praetextati) right next to a section for their paedagogi, no doubt so the boys would be less unruly. Paedagogi were charged with constantly monitoring a youth’s public behavior, in the streets, at meals, at shows, or in the atria of important men. The emperor Galba had three corrupt cronies who never left his side in public, and they were jokingly referred to as his paedagogi.

The use of corporal punishment was widely endured but criticized by enlightened educationalists such as Quintilian. Like primary teachers, they used a rod made of giant fennel, the ferula, because it left few scars. The poet Martial calls it “the sinister rod, sceptre of the paedagogus.” When the young man was of the imperial house, however, more subtle methods might have to be used. The twelve-year-old future emperor Commodus once demanded, when his bathing room was too cool, that the bath slave in charge be thrown into the furnace. His paedagogus discretely had a sheep skin thrown into the furnace, the acrid smell of which convinced Commodus that his order had been carried out. Traditionally humorless, the paedagogus had as his job not so much education as behavioral control. Some might earn the affection of their charges, but as a type, they were not loved. Nero had the respected senator and devotee of Stoic philosophy Thrasea Paetus executed, by one account, “because he wore the miserable expression of a paedagogus.”

An educated Greek, who could teach the boy how to speak proper Greek, was the best sort of paedagogus to have, but this of course was not always possible. Nero, who grew up in relative poverty, was said to have had two paedagogi as a young boy, a barber and a dancer. Augustus punished the corrupt paedagogus of his son Gaius for a serious offence by having him thrown into a river with weights around his neck. Claudius complained in his memoirs about being assigned a cruel barbarian for a tutor, who was given specific instructions to beat him with the slightest provocation.

The word dies out in the Middle Ages, because the custom itself faded with the prosperity of the high empire. But in the meantime it made an interesting detour in Christian Greek. St. Paul compared the law of the Jews to a paedagogus who disciplines us and shows us how to act, until the higher instruction of Christian faith gives us independent moral agency. Picking up on this idea, St. Clement of Alexandria in the late second century wrote an entire treatise called Paedagogus, which gives instructions on a Christian lifestyle for those who, though they have committed to a Christian life, have not advanced all the way to perfect Christian wisdom. It contains advice on what to wear, how to walk, how to kiss, and many other aspects of proper behavior for women and men.

In English, pedagogue resurfaced in the late 1300s, as a synonym for schoolmaster. It thus took a Roman rather than a Greek connotation, since while Roman paedagogi did do some language teaching, their Greek counterparts did not. The pedagogue has continued his rise up the educational ladder, until today pedagogy suggests not mere instruction but sophisticated teaching techniques based on some kind of scientific system—a vice of which the Roman paedagogus could not be accused.

References: TLL 10.31–34. RE 18.2375–2385. Theater seating: Suetonius, Augustus 44.2. Galba: Suetonius, Galba 14.2. Quintilian: On the Orator’s Education 1.3.15. Martial, Epigrams 10.62.10. Commodus: SHA, Commodus 1.9. Thrasea Paetus: Suetonius, Nero 37.1. Nero’s paedagogi: Suetonius, Nero 6.3. Thrown into a river: Suetonius, Augustus 67.2. Cruel barbarians: Suetonius, Claudius 2.2. Paul: Letter to the Galatians 3.24.

Adapted from the book Ancient Rome in So Many Words (New York: Hippocrene, 2007) by Christopher Francese.

Adapted from the book Ancient Rome in So Many Words (New York: Hippocrene, 2007) by Christopher Francese.