Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World App. Princeton University Press, 2013. iTunes $19.95 US.

Reviewed by Meagan Ayer, Dickinson College (ayerm@dickinson.edu)

iTunes preview

In December 2013 Princeton University Press launched the much anticipated app version of its Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. The original print version of the Atlas, overseen by Richard J. A. Talbert and published in 2000, was the first atlas to provide comprehensive maps of ancient Greek and Roman territories stretching from Britain to India and Africa. It immediately became the standard for maps of that part of the ancient world. The extent of territory and level of detail required that the atlas be large (13.25 x 18 in. unopened), and its high quality came at a fairly high price (currently $395 US), which meant that “the Barrington” was not always easily accessible to individuals. The application is, therefore, a welcome effort to make all the scholarship of the Barrington Atlas available to individuals anywhere at anytime.

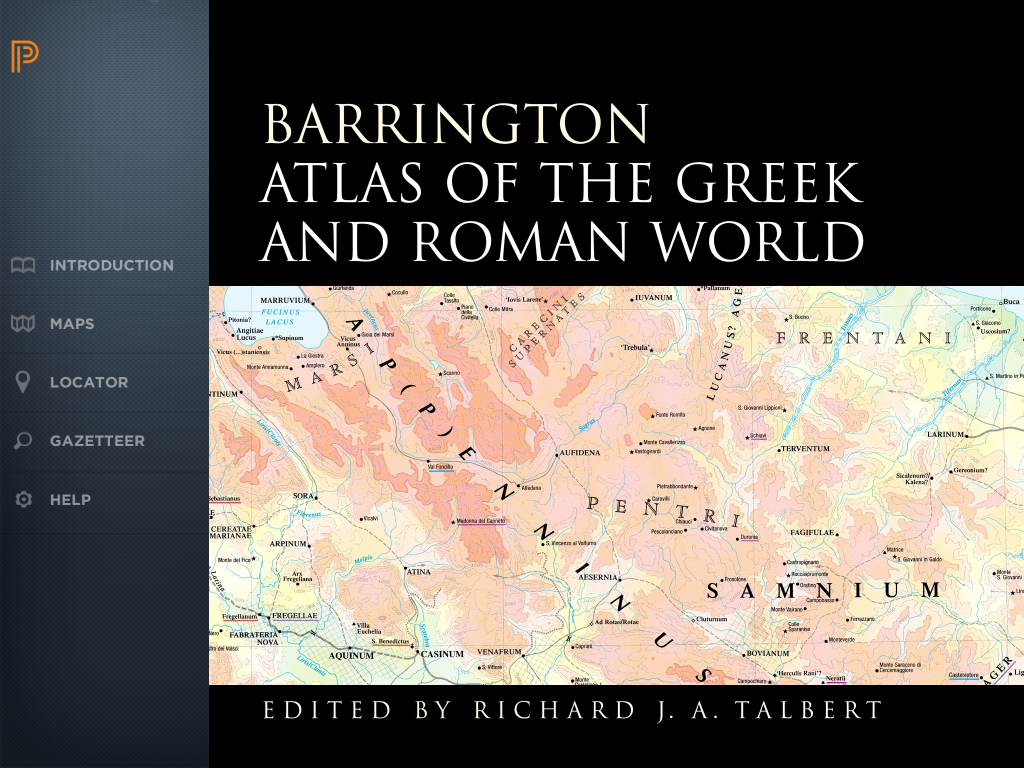

The app itself is surprisingly small, weighing in at only 411 MB. In this compact package you have access to all 102 maps of the original Barrington which are stored locally, allowing the user to browse maps on an iPad without being connected to the internet. Upon opening the app, the Princeton University Press logo appears, followed by a cropped version of the dust cover from the print version. In order to access the application features from here, it is necessary to either tap the screen or swipe from left to right. Doing so reveals the navigation menu.

Navigation Menu

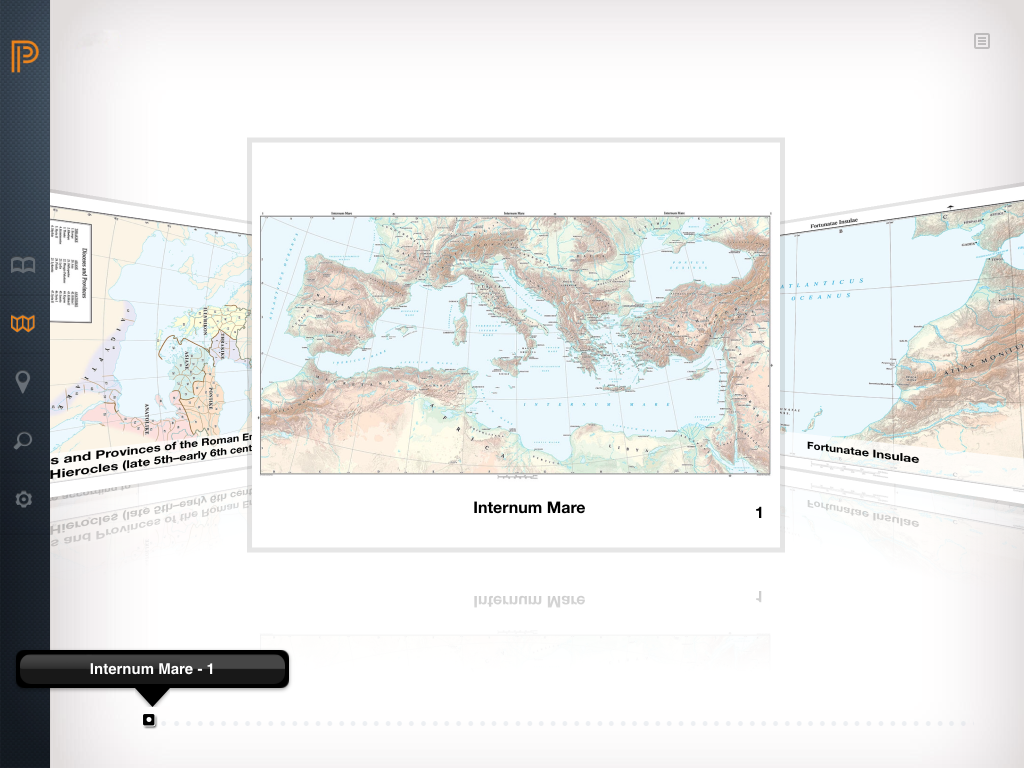

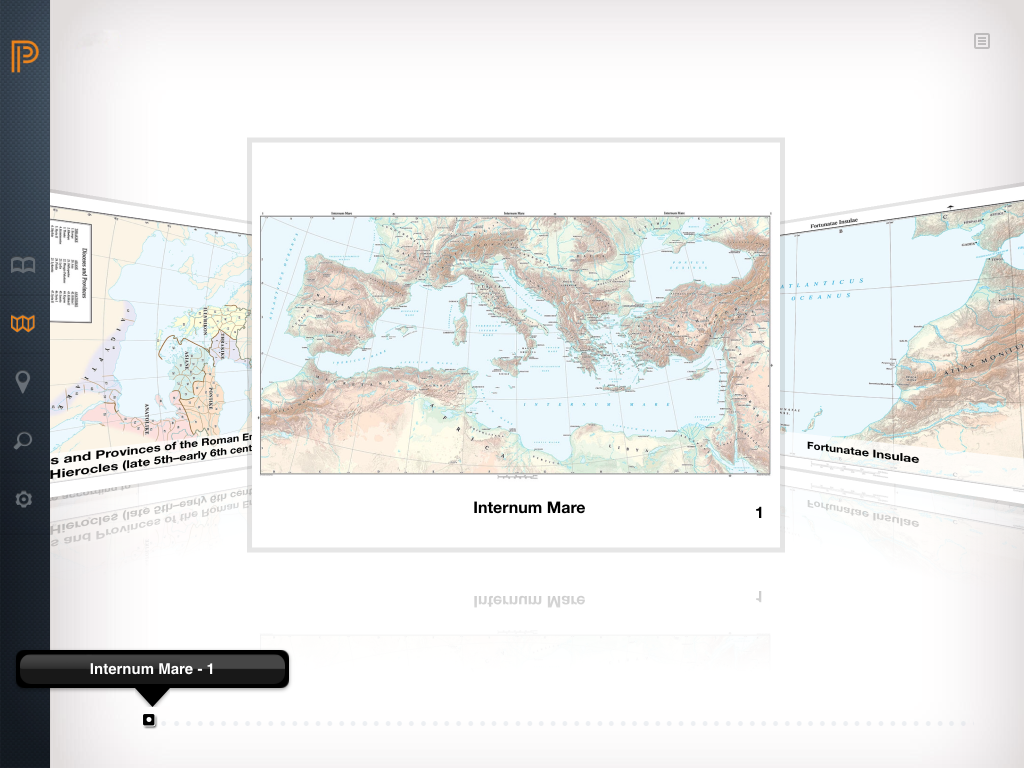

There are three different ways to view the content of the atlas. If you simply wish to browse the maps you can select the Maps tab. This will load a thumbnail gallery of all the maps in the atlas which you can flip through before tapping on a particular map to select it.

Thumbnail Gallery

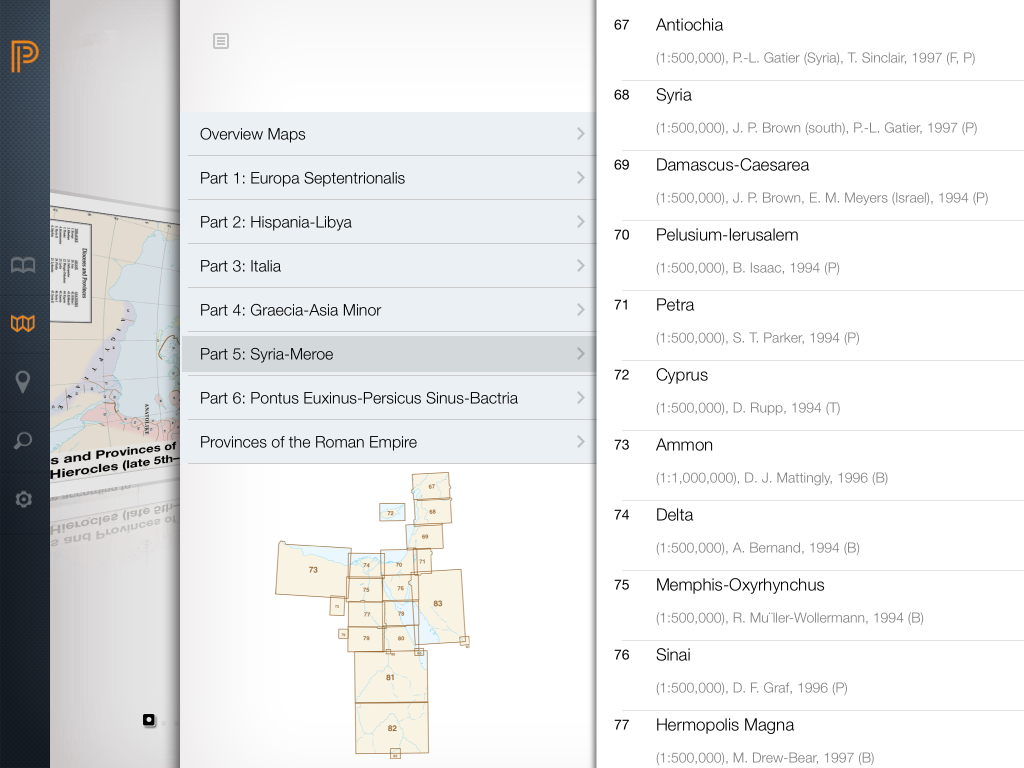

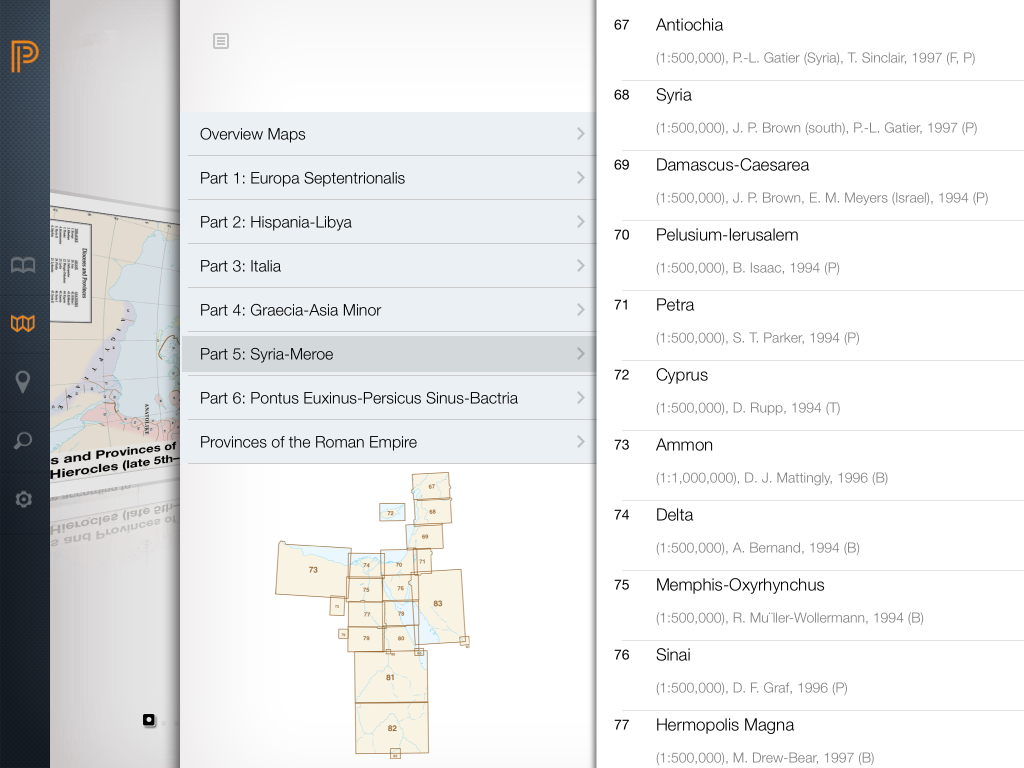

Alternatively, a navigational menu button in the upper right hand corner of the gallery allows for the selection of maps by region. Simply open the menu, choose your larger region and then select a specific map.

Selecting Maps by Region

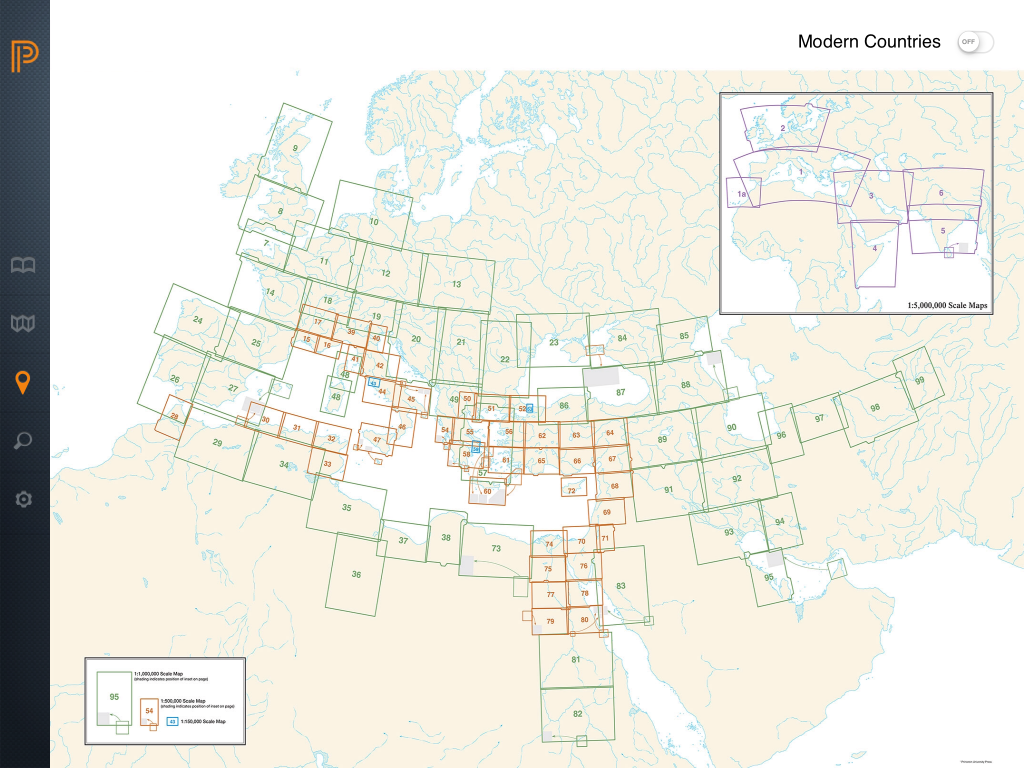

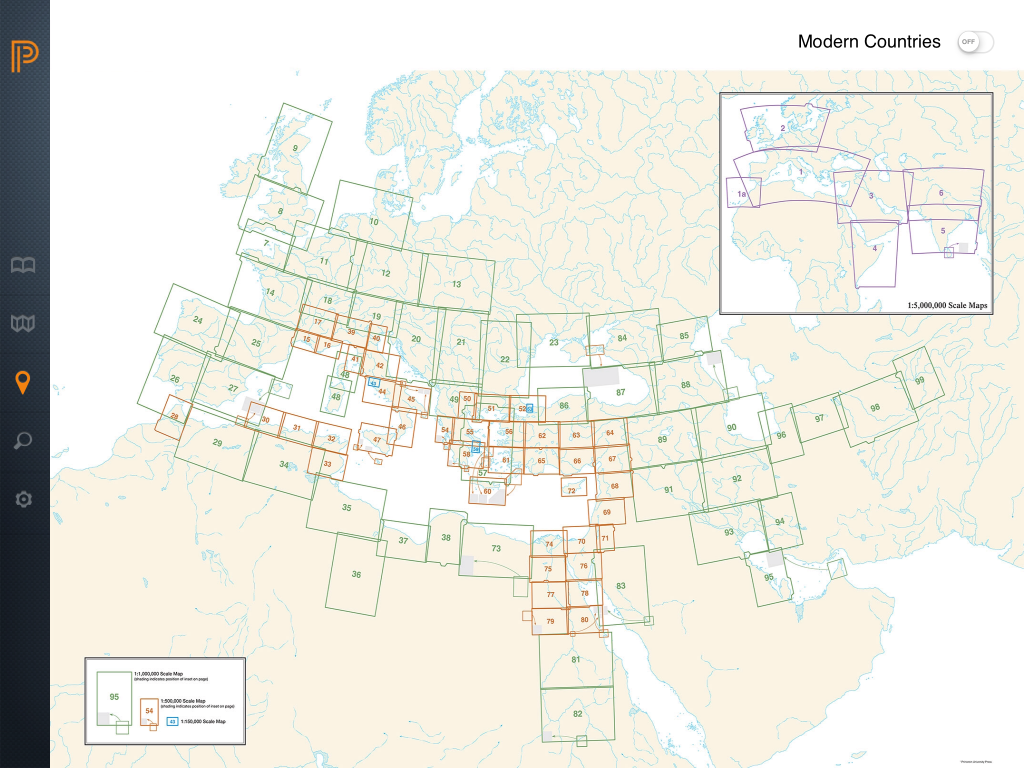

One can also use the Locator tab, which pulls up a map displaying the entire area covered by the atlas overlaid with boxes corresponding to individual maps. If you wanted to view a map of the Nile delta you could simply select box 74 to be taken to that map. If you are looking for maps of ancient sites within a modern country, a button is also provided in the upper right hand corner to turn on and off modern borders.

Map Locator

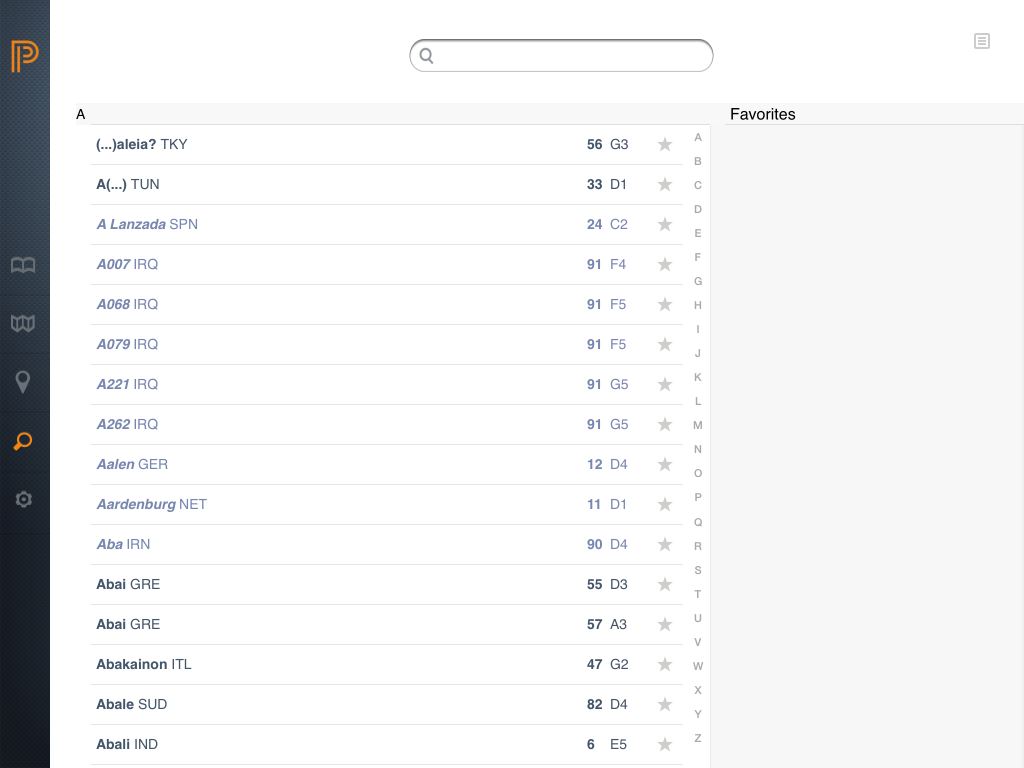

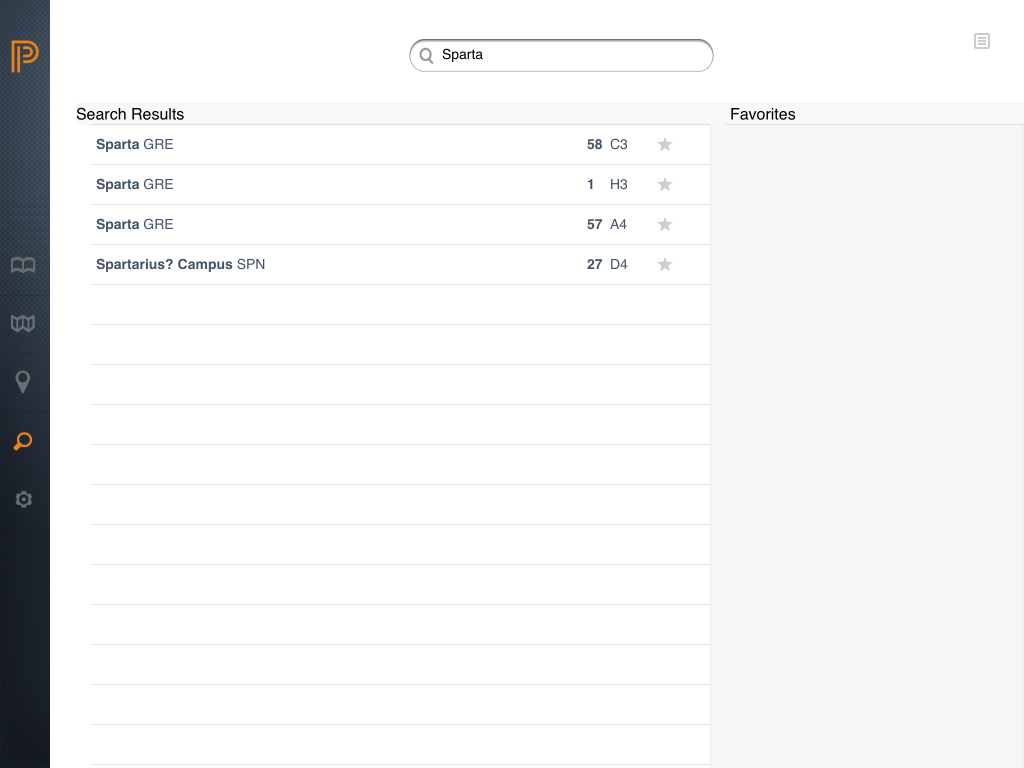

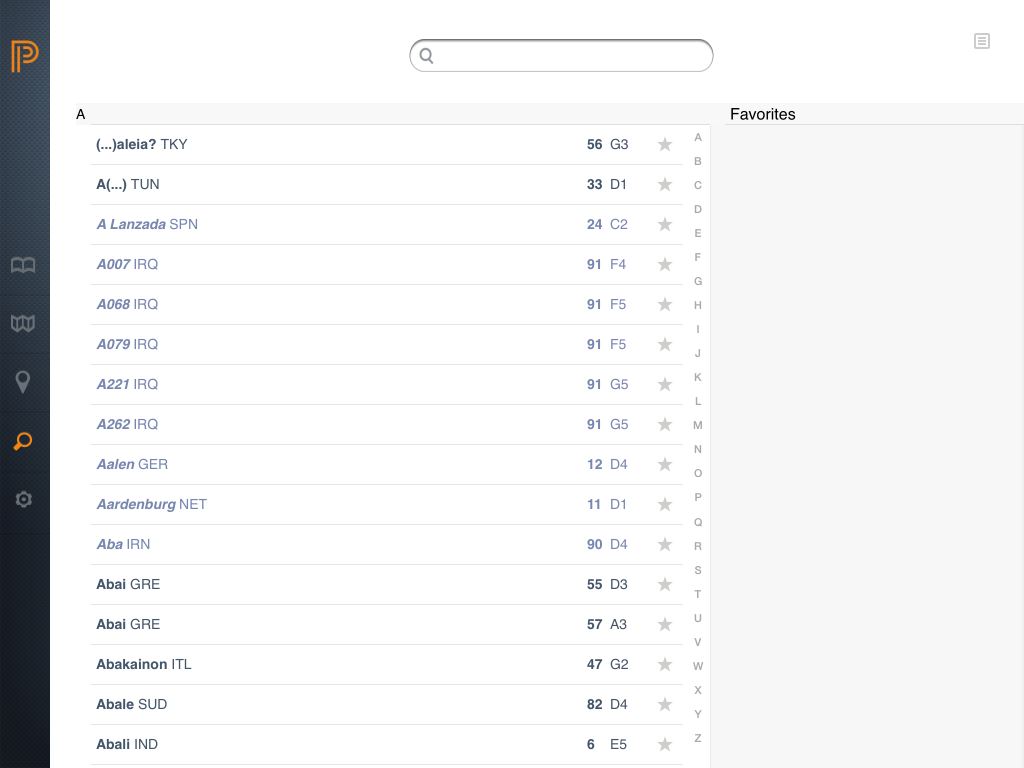

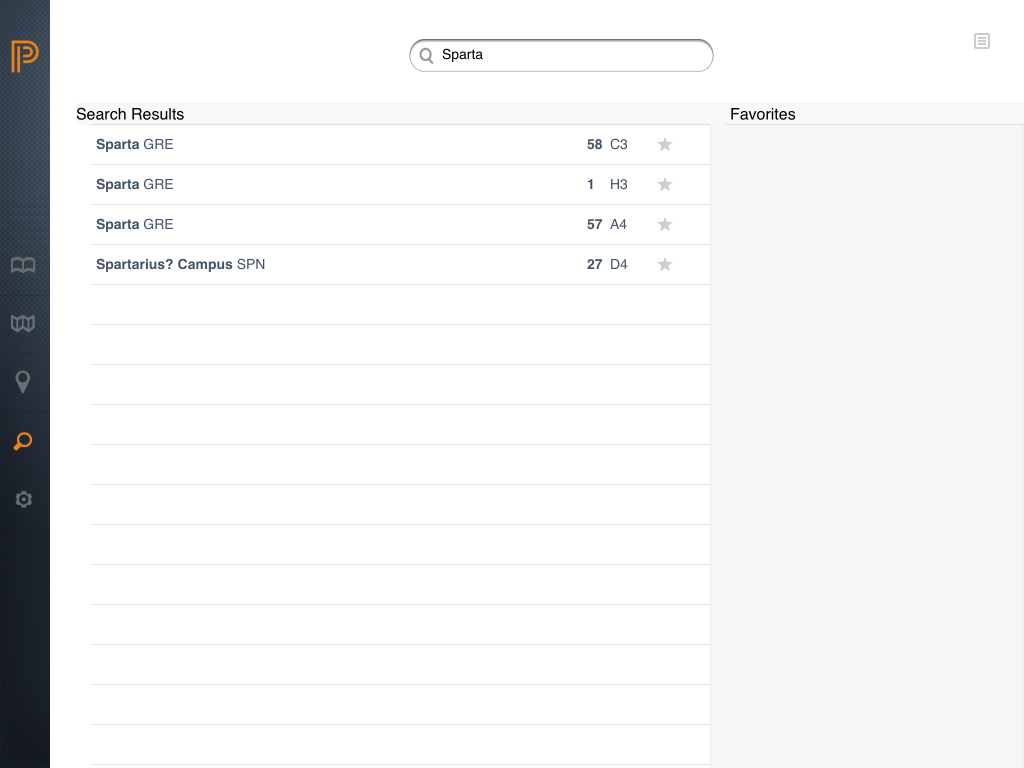

Finally, you might be searching for a specific site in the atlas. Selecting the Gazetteer tab opens a searchable alphabetical listing of all the sites included in the atlas. A pop-out drawer located in the upper right hand corner of the screen explains the organization of modern and ancient site names as well as country abbreviations. Searching for a site returns links to each map on which that site appears.

Gazetteer Tab

Unfortunately, search results are not saved, so that if you click through to one map, the search must be performed again to see the other maps. It is possible, though, to save individual maps to the Favorites section by tapping the star icon to the right of the map coordinates.

Saving Maps to Favorites

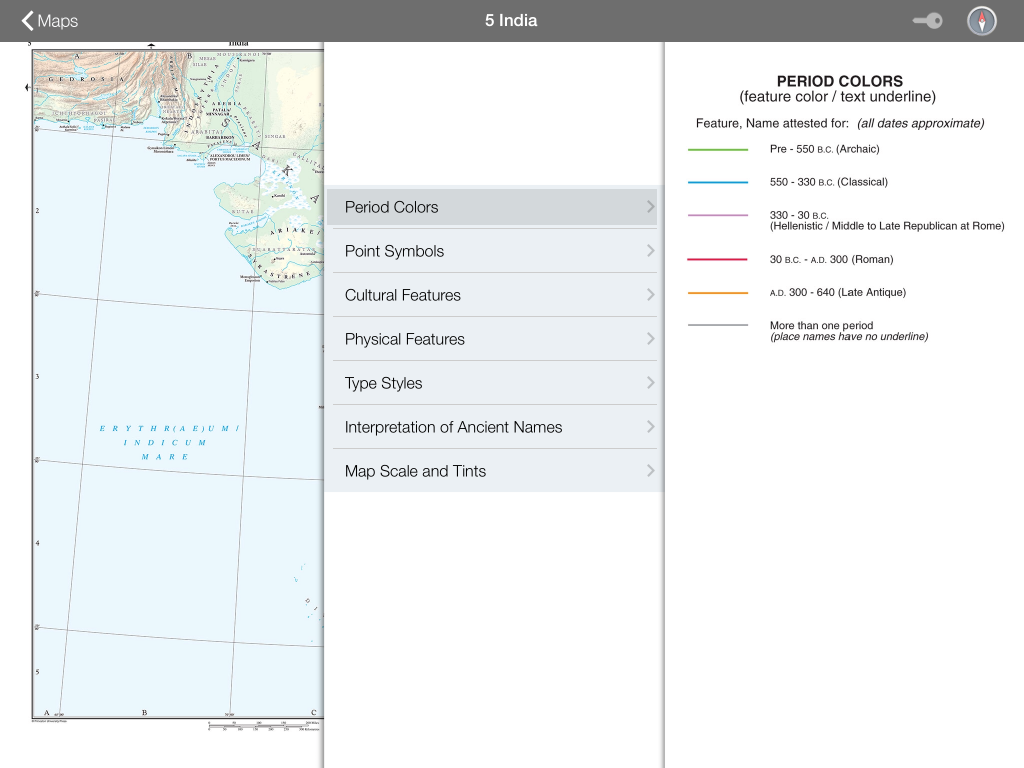

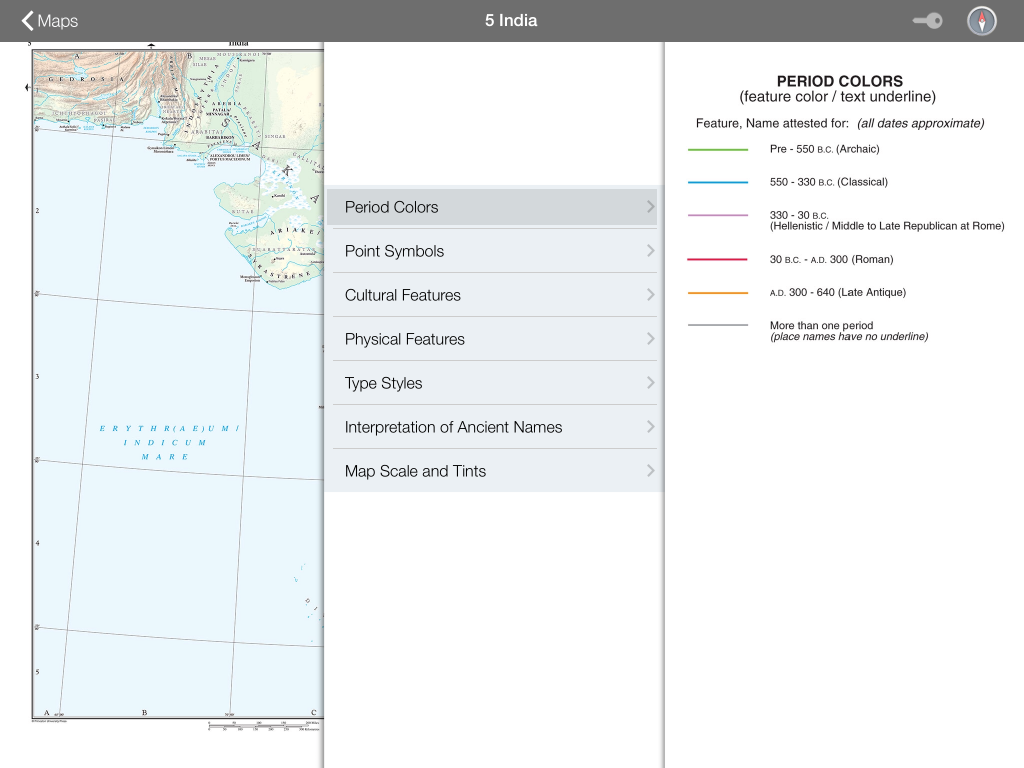

There are a few interesting features within the maps themselves. Tapping in the center of a map drops down a tool bar containing key and compass icons. Selecting the key icon slides out two drawers from the right which elucidate the symbols and coding of features and time periods on the map. This is a vast improvement over the print edition which required flipping back and forth within the atlas to read the key.

Key

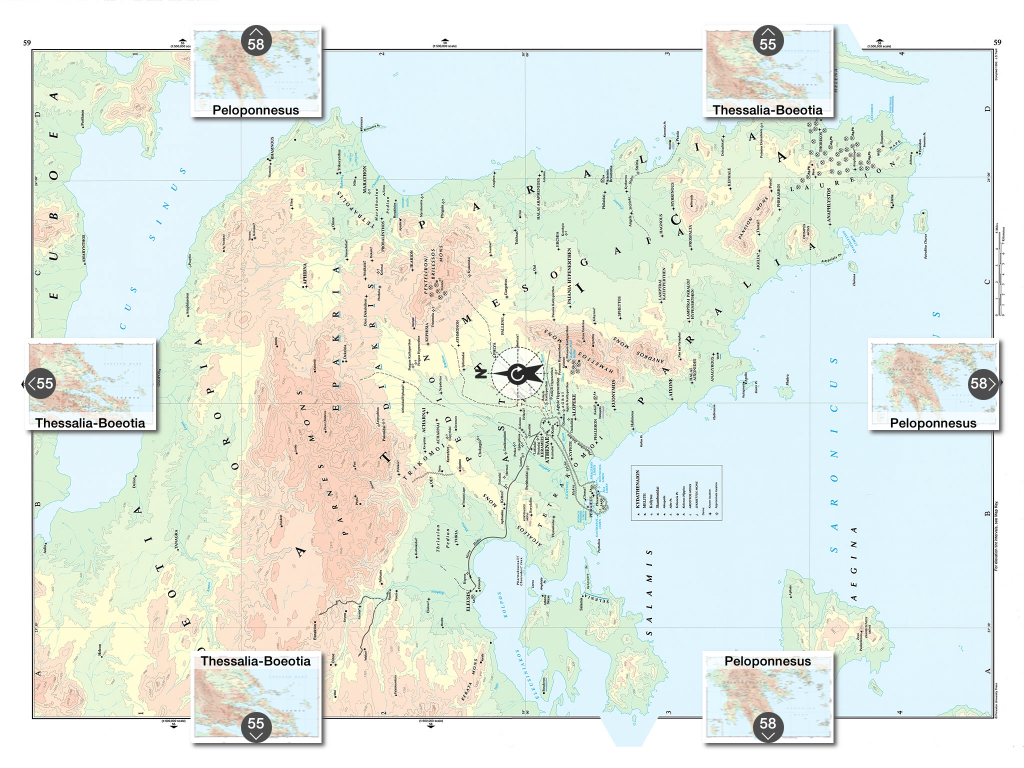

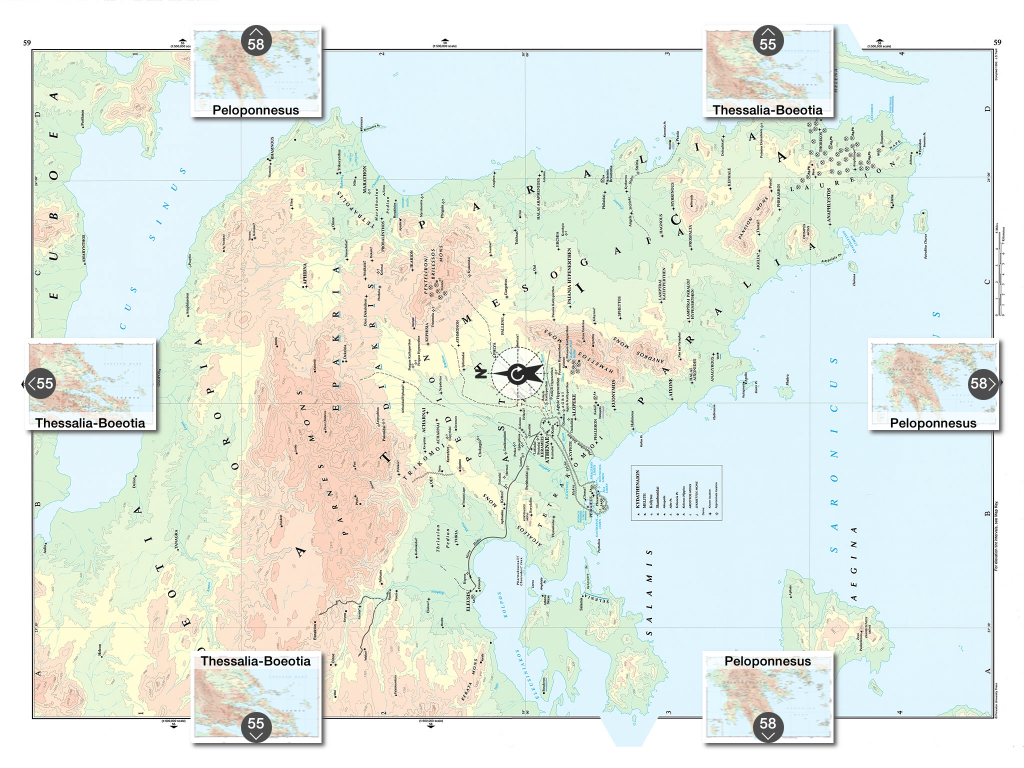

Tapping the compass icon in the tool bar reveals thumbnail maps of adjoining regions that can be used as short cuts to those maps. Additionally, a large compass icon appears in the center of the screen; touching this icon reorients maps so that true north appears at the top of the screen.

Compass icon in the tool bar reveals thumbnail maps of adjoining regions

It also enlarges the map, which is less useful, forcing you to carefully zoom out again to see most of the map. It is extremely easy to accidentally zoom entirely out of a map and into the map browser; the creators might consider removing the feature allowing users to zoom out to the map gallery as it serves little purpose and can result in some frustration.

Version 1.1 has already begun to address some of the issues noted by early adopters. The app no longer cycles through the start-up sequence again after backgrounding; instead it picks up on the page or map last viewed. Stability has also been greatly increased. In version 1.0 the app was given to crashing during navigation, however, I have not experienced any crashing since upgrading to version 1.1. Also, smaller symbols and place names on maps that would often appear slightly blurry in version 1.0 when fully zoomed in, are crisp and easily read in version 1.1.

Still there are a few missteps, almost all of which appear to result from mimicking the print volume in digital format too closely. For example, the Introduction tab simply replicates the same material of the print edition, including table of contents and credits. While the introduction itself is worth reading, I am not certain how useful the table of contents from the print edition is within a digital app. It seems unlikely that someone searching for a map would backtrack to the introduction rather than simply use the browse or list features. Moreover, the short tutorial provided for the app is static and buried in the help section of the main menu. It would be beneficial to either pop-up the tutorial the first time the app is opened or run a short video illustrating how to navigate the app.

I could wish for more interactive features within the app, such as the ability to plot routes and otherwise manipulate the maps— similar to what is found in the Ancient World Mapping Center’s on-line tool Antiquity á la Carte— but that would, I suspect, require designing entirely new maps from the ground up. I might also wish that the app was available on more platforms. As of this moment it is limited to Apple’s iOS, preventing Android tablet owners from using this wonderful resource.

Overall, the app version of the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman Worlds is an admirable effort. It provides all the information and resources of the original Barrington Atlas in an easily transportable format at a fraction of the cost. It is significantly more accessible to students and scholars at home or on the road and I suspect that, like its predecessor, it will become a standard tool for students of the ancient world.

This review of the Barrington Atlas App tested version 1.1 and was conducted on a 128GB iPad Air running iOS 7.0.4.

Dr. David Gilman Romano, Karabots Professor of Greek Archaeology at the School of Anthropology, University of Arizona, and Director of the Corinth Computer Project and the Archaeological Mapping Lab

Dr. David Gilman Romano, Karabots Professor of Greek Archaeology at the School of Anthropology, University of Arizona, and Director of the Corinth Computer Project and the Archaeological Mapping Lab Dr. Nicholas Stapp, Director of Geospatial Research at the Archaeological Mapping Lab at the University of Arizona

Dr. Nicholas Stapp, Director of Geospatial Research at the Archaeological Mapping Lab at the University of Arizona