Proposal

Scope:

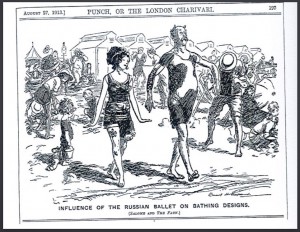

Over the course of the semester I am conducting research on the dispersion of Russian culture from 1909-1929 through the Ballet Russes and the immediate years following its’ dissolution and dispersion of members. Immediately following the dissolution of the Ballet Russes, the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo was formed by former members who continued on the practices in a smaller capacity. By examining the spheres of popular culture and fashion (both social and theatrical), I will determine how culture changed and evolved over time. Historical occurrences will be taken into account only to the extent of providing context for the spread of Russian culture.

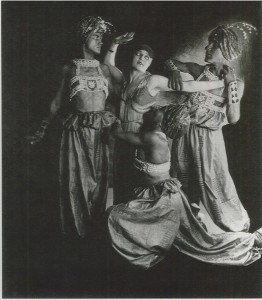

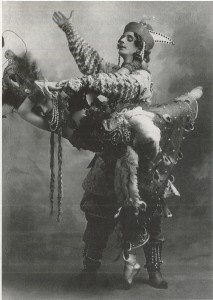

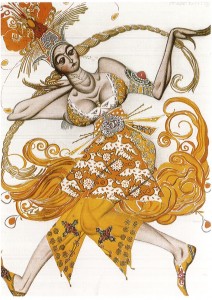

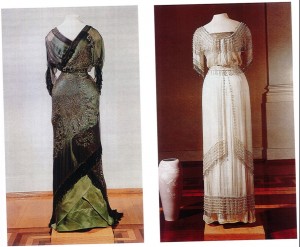

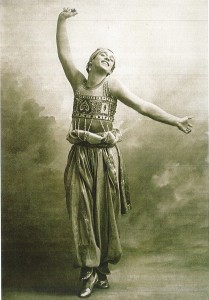

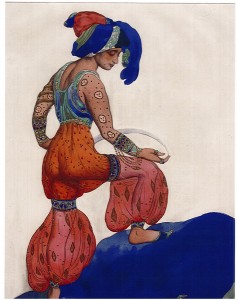

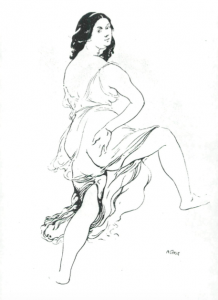

The majority of cultural research that I have gathered thus far relates to costumes and clothing. The expression of culture through clothing is of particular interest to me, especially because prior to the Ballet Russes ballet costumes were extremely rigid, and rarely varied from the traditional tutu. With the increase of fluid motion in Ballet Russes’ choreography styles began to transition into more freely flowing garments. This new fluidity allowed greater expression and emotion through movement. Men’s roles also evolved with the Ballet Russes along with their garments. Traditionally men were viewed as an assistant to the ballerina, but then they took on a more active presence on stage and their clothing followed suit.

Value and Originality:

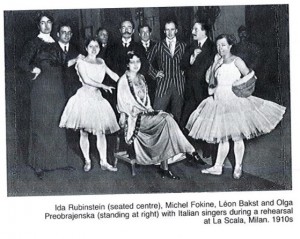

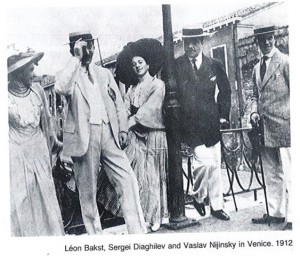

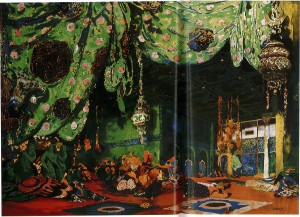

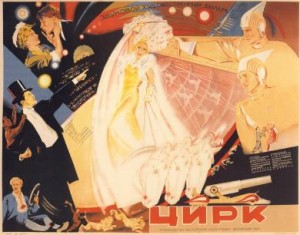

While scholarship on the dispersion of Russian culture via the Ballet Russes already exists, I will be focusing on the sphere of fashions and costumes to convey the pertinent information. The Ballet Russes were a visual spectacle, and yet there is nearly no existing footage of a performance; a lone thirty-second clip of an outdoor rehearsal. This clip was filmed without the consent of Diaghilev, the creater of the Ballet Russes. The lengths to which Diaghilev went to ensure high box office sales were to the point where choreography and details gained from physically experiencing his spectacular performances have been lost over time due to a lack of video documentation. Many photographs of costumes and set designs were taken during the time of the Ballet Russes, but the fluidity and motion, for which the ballet was renown, was kept within the company. This reliance on costumes to envision the Ballet Russes performances particularly interests me, because so much is left to interpretation and lost to history. I believe that my research will be unique in that I am examining the relationship between popular culture fashion and theatrical fashion, because a symbiotic relationship existed between the two factors.

Through research I hope to discover to what extent social and theatrical clothing were related, and which had greater influence over the other. In the instance of the production Le Train Bleu, the famous designer Coco Chanel designed the costumes for the athletic beach inspired ballet. For this particular production it is clear that modern fashion was the inspiration, but the source of inspiration is not always so obvious. In many of the Ballet Russes productions cultural Russian garb was reproduced for the stage, which causes the question to arise whether these styles became en vogue once again do to their reoccurrence. To aid in my quest for answers to these questions Robert Hansen and Roger Leong in Scenic and Costume Design for the Ballet Russes and From Russia With Love, respectively detail the costume designs used in their books and their origins of design and fabrication.

Practicality:

At this point in research I have struggled in finding primary resources, however I have found many secondary sources. The main primary resource that I have come across is embedded within a secondary source, the DVD Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes. In the film is a short clip of a Ballet Russes performance. This is an extremely vital piece of information as it is the only existing video footage of the Ballet Russes. Original sketches and set designs are also primary sources, which I am referencing, the main lacking primary resources are written works.

Bibliography

Aldrich, Elizabeth. “Serge Diaghilev and His World Examined.” Library Of Congress Information Bulletin 68, no. 7/8 July 2009, 131-132.

Anderson, Jack. The One and Only: The Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo. New York: Dance Horizons, 1981.

The time period after the death of Diaghilev was one in which the former members of The Ballet Russes split off individually to begin their own chapters of ballet. The author illustrates the various was in which the ballet adapts once it splits off, but recognizes that as a whole the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo did not make any great moves of it’s own. For my purposes I will use the continuation of the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo as proof of the worldwide appeal and desire to adopt this new style of ballet into each culture. Using photographs and primary sources such as local newspapers Anderson supports his claims throughout the book.

Anderson, Jack. “The Enduring Relevance of Léonide Massine.” Experiment: A Journal Of Russian Culture 17, no. 1 (January 2011): 256-263.

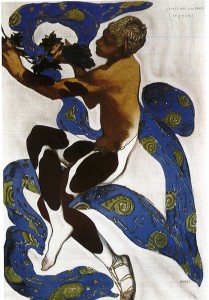

Bakst, Léon. Léon Bakst: Set and Costume Designs, Book Illustrations, Paintings and Graphic Works. Comp. Irina Nikolaevna Pruzhan. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Viking, 1987.

Barnes, Clive. “Cincinnati Ballet.” Dance Magazine 17, no. 2, February 2003.

Caddy, Davinia. The Ballet Russes and Beyond: Music and Dance in Belle-Epoque Paris. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

France is arguably the most influenced country by the Ballet Russes, as the group originated to perform to the high society in France. Evidence is presented in this novel, which reveals how the French style of dance evolved due to the influence of the Ballet Ruses. Caddy’s thesis builds on historically linking events through history into one smooth streamlined timeline. In my paper I will be able to link the influence of the ballet Russes to shifts in tone and style in French theatrical realms, displaying the universality of dance and music.

Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes. Produced by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, on the occasion of the exhibition Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes, 1909-1929: When Art Danced with Music. 2013, DVD.

This film was created in conjunction with an exhibit by the same name at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC as an overview of the History of the Ballet Russes. Using interviews of former dancers, historians and a composer, the viewer is able to gain a broad view of the history and impact of the Ballet Russes. The DVD inserts multiple clips of ballet performances, including the only existing film fragment of a Ballet Russes performance. As an extremely visual spectacle of art, this video aids in my understanding of the movement and practice of the ballet in order to understand what it would have been like to witness a live performance in full. The interviews placed throughout the film provide diverse perspectives on the actions taken by Diaghilev during his time running the ballet.

Garafola, Lynn. “Dance, film, and the Ballets Russes.” Dance Research: The Journal Of The Society For Dance Research 16, no. 1 (Summer 1998): 3-25.

Garafola, Lynn. Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

In the interest of dissecting the result of the Ballet Ruses and the world, it must first be understood how the group came to be and how the creative decisions came about. The company never actually performed in Russia, it’s roots were in trying to get Parisians to gain a favorable impression of Russia in order for the Tsar to receive a loan form France. With a background in imperialist Russia the direction in which the troupe developed can be contextually analyzed. Garafola employs photographs and primary and secondary sources to trace the development of the company. For my paper it is necessary to be able to trace historical events to their impacts on and development of production themes and adjustments.

George, Adrian. “The Art of Dance.” Dance Theatre Journal 18, no. 2 (2002): 20-24.

Haldey, Olga. “Savva Mamontov, Serge Diaghilev, and a Rocky Path to Modernism.” The Journal of Musicology 22 no. 4 (2005): 559-603.

Hansen, Robert C. Scenic and Costume Design for the Ballet Russes. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1985.

By chronologically investigating the performances of the Ballet Ruses, Hansen is able to smoothly trace influence from its originating performance and costume designs. With the research method chosen by Hansen, he can attribute each identified trend to the current creative director at the time. Taking into account photographs of costumes and performances and multiple secondary and primary sources Hansen comes to the conclusion that it was the combined effort of the Ballet Russes, which ultimately led to its wide success. To prove the significance of this establishment of the Ballet Russes Company I must be able to attribute variances in style and choices to the management at the time, and I am able to do this with the aid of the detailed case study of costumes.

Jackson, Barry. “Diaghilev: Lighting Designer.” Dance Chronicle 14, no. 1 (1991): 1-33.

Kennedy, Janet. “Pride and Prejudice: Serge Diaghilev, the Ballet Russes, and the French Public.” In Art, Culture, and National Identity in Fin-de-siècle Europe, ed. Michelle Facos and Sharon L. Hirsh, 90-118. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003.

Leong, Roger. From Russia With Love: Costumes for the Ballet Russes 1909-1933. Australia: National Gallery of Australia, 1998.

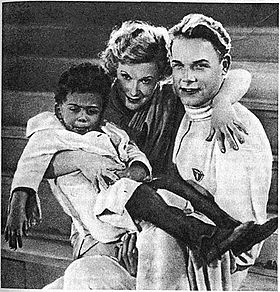

Similarly to the above DVD, this book focuses on the costume design and symbolism and significance they had. As this book was published in Australia, the main thesis is concerned with displaying how Australian ballet and dance were forever influenced by the Ballet Russes. I will use this resource in order to bring visual representation to my research.

Massie, Suzanne. Land of the Firebird. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980.

In this highly specific case study of The Firebird, every aspect is detailed and investigated. Specifically interesting to me is the success garnered by the performance because of its heavily Russian theme and perceived exoticness. Parisian crowds were in awe of the rich Russian sound in combination with the highly emotive dancers, which were a complete departure from traditional practices of the day. I will use this source to enforce the influence of the Ballet Russes and also to link performance success with Russian cultural ties.

Ostlere, Hilary. “Saluting the theatrical Diaghilev.” Dance Magazine 72, February 1998.

Potter, Michelle. “Designed for Dance: The Costumes of Léon Bakst and the Art of Isadora Duncan.” Dance Chronicle, 1990.

Pritchard, Jane. Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, 1909-1929: When art danced with music. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2013.

Ruane, Christine. The Empire’s New Clothes: A History of the Russian Fashion Industry, 1700-1917. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2009.

The heyday of the Ballet Russes coincided with multiple historical events and changes in society, which were reflected in the clothing and costumes worn for Ballet Russes productions. The belief that “Russian art should make its own contribution to European art… defined a new artistic movement on the Russian art scene”. ((Christine Ruane, The Empire’s New Clothes: A History of the Russian Fashion Industry, 1700-1917 (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2009), 171.)) In striving to make it’s own mark on the industry, the Ballet Ruses ushered on a wave of modernity, which is observable thought shifts in clothing. By analyzing the photographs and sketches of the ballet costumes I will be able to assess the connection between modernity and Russian folk roots in the popular spread of the art.

Winestein, Anna. “Quiet Revolutionaries: The ‘Mir Iskusstva’ Movement and Russian Design.” Journal of Design History 21, no. 4 (2008): 315-333.

Part 1: http://blogs.dickinson.edu/quallsk/2016/05/03/ballet-russes-the-early-years-part-1-of-6/

Part 2: http://blogs.dickinson.edu/quallsk/2016/05/03/leon-bakst-and-scheherazade-part-2-of-5/

Part 3: http://blogs.dickinson.edu/quallsk/2016/05/03/the-loss-of-gesamtkunstwerk-part-3-of-5/

Part 4: http://blogs.dickinson.edu/quallsk/2016/05/03/images-of-the-ballet-russes-part-4-of-5/