Of the scholarly websites and books that I am using for this project I have found a number of similarities. Many of these sources are a form of anthology, where books have chapters the web sites have pages. But, a very distinct feature of the web site is its growth and development. Where a book would have to be republished, or have additional volumes, a web site allows for scholars to access and revise a number of times with relative ease. Additionally, on some internet outlets, the sites allow for commenting on articles or provide links to response pieces. This illustrates an evolving dialogue in the field that a book is, by nature, unable to provide.

In looking for the number of multimedia sources that this project has prescribed I have developed a number of skills that have already begun to help me in other areas of my research. I have found that much of a topic’s philosophy and history is easiest found in reliable scholarly texts, but having websites or scholarly blogs provide more contemporary and evolving views.

As for my review of Evernote, I must say that it has been difficult to preserve the bibliographies’ citation format while using the program. I have found it useful for storing snippets of information for personal use, as I can access it across platforms. I did not find myself using Evernote to discover other information gathered by users that might pertain to my research, but I can see such a service being useful. Ultimately, the service falls short of our primary need for it — class sourcing — when our primarily shared document, the bibliography, is so negatively affected.

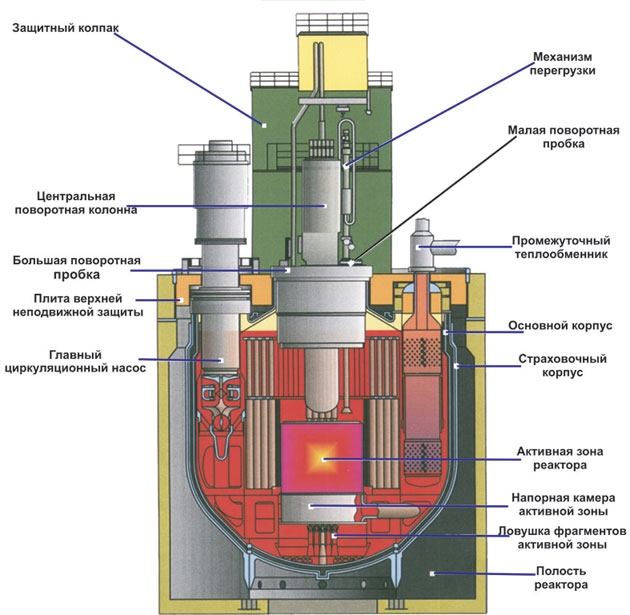

I have begun plotting a timeline. By going through each source and plotting relevant data on a time scale, I can identify patterns of change. Already I have found correlations between the evolution of reactor designs and the “Green Movement” starting in the 1980, which was unexpected. Many of my preconceptions of Soviet nuclear policy have been changed by the research I’ve done and I feel far more open to interpreting the information than using it to support what I believed to be true.

Here’s a link to my bibliography:

Has diary writing survived? Is there something comparable now?

Has diary writing survived? Is there something comparable now? Consider them in the context of popular social networks. Imagine the most cautious user — only friends can see their posts, does not use an accurate identifying picture, and only accepts requests from close, close, friends. Their records can be obtained by any determined individual, similar to the Stalinist state. But, our user runs this risk. On such sites, our user hopes to associate and connect with like-minded individuals. Is this not what Podlubni hopes to accomplish? A connection with the other members of his State through the fashioning of his personality, of his “Stalinist soul”.

Consider them in the context of popular social networks. Imagine the most cautious user — only friends can see their posts, does not use an accurate identifying picture, and only accepts requests from close, close, friends. Their records can be obtained by any determined individual, similar to the Stalinist state. But, our user runs this risk. On such sites, our user hopes to associate and connect with like-minded individuals. Is this not what Podlubni hopes to accomplish? A connection with the other members of his State through the fashioning of his personality, of his “Stalinist soul”.