Is a politician’s image imposed externally, by admirers and critics located domestically as well as abroad, examining the politician within his respective surrounding context and time period? [Bottom-up] Or, on the other hand, does a ruler paint his own political picture, a self-created phenomenon, descending internally from the ruler himself? [Top-down] This is the question that R. J. B. Bosworth examines in a chapter of his 1998 publication, “Mussolini the Duce: Sawdust Caesar, Roman Statesman or Dictator Minor?”. Truly, as Bosworth illuminates based on multiple academic’s opinions of Benito Mussolini during and after his reign of power, a politician’s image is both a combination of self-determining propaganda and external popular evaluation.

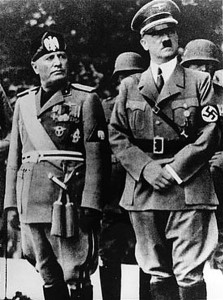

Mussolini ruled as a charismatic leader, relying upon his positive public image to reinforce his extremist Fascist party ideology and state. While the Duce’s dictatorship and personality paled in comparison to Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia (hence the Dictator Minor label), all three rulers shared in common a tendency toward the ‘Great Man’ approach. This approach to history evaluates a leader based on his heroism as the determining force of his historical impact. As Bosworth asserts, normally this approach to analyzing history is “well out of favor” but “to some extent, however, the history of Fascism and, more generally, that of twentieth-century European politics, is an exception to that rule.” ((B.J.B Bosworth, “Mussolini the Duce; Sawdust Caesar, Roman Statesman or Dictator Minor?” The Italian Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives in the Interpretation of Mussolini and Fascism, London: Arnold, 1998, 74. 59 ))

Bosworth examines how over the course of Mussolini’s dictatorship from 1922 – 1943, the effective influence of Mussolini’s fascist rule lost power parallel to the decline of what Emilio Gentile calls, ‘the imagined Mussolini’. Passerini accepts Gentile’s view “that Fascism brought mythical thought to power.” (( Bosworth, “Mussolini the Duce”, 61. )) Other historians, throughout Bosworth’s article, refer to this grandiose conception of Mussolini as ‘the myth of Mussolini.’ When Mussolini rose to power, he did so under the pretense of embodying the values of the Italian public, as a “medium of a mass age.” (( Bosworth, “Mussolini the Duce”, 62. )) Public reverence for the heroic dictator reached levels of deep religious awe; Mussolini’s call for a New, collectivist, Italy resonated deep in the Risorgimento national spirit. Italy was traditionally a diverse and separated country, even after the Italian Unification of the 19th century – Could Mussolini finally be the leader destined to bring together the Italian people into a united nation? Mussolini capitalized on the declining pre-modern Catholic papal influence to replace with a modern religious appreciation of the secular state. But after 1925, when Mussolini decided against ruling by the Italian Constitution and created his own pseudo-legal totalitarian state, public adoration turned to public crucifixion.

Especially when Mussolini – always an an advocate of aggression rejecting the doctrine of pacifism – joined the WWII offensive in June 1940, with a false consolation to the Italian masses that it would be a short-lived dispute, public opinion of him really fell out of favor when increasing global military conflict created a sense of betrayal within the Italian people. Bosworth extols this concept, “Figures blessed or afflicted by charisma may, of course, be hated as well as loved. Prayers to the good Mussolini were matched by anathemas to the evil one.” (( Bosworth, “Mussolini the Duce”, 65 )) While the Duce may have been a master propagandist in his own right, his pervasive slogan, ‘Mussolini is always right’ will go down in history as an ironic catchphrase, as his resonant historical image, in the words of Bosworth, is as war-time Europe’s “failed dictator.” (( Bosworth, “Mussolini the Duce”, 59 ))

Based on your understanding of each of the dictator’s cult of personality and their respective states (Mussolini’s Fascist Italy, Stalin’s Communist Russia, and Hitler’s Nazi Germany), do you believe that Bosworth’s concluding assessment of Mussolini’s “image of a failed dictator, at least in contrast with Hitler and Stalin” (( Bosworth, “Mussolini the Duce”, 59 )) is an accurate evaluation?