Dec 2017

The Human Face of the Enemy

English and American Cinematic Depictions of Nazi-era Naval Personnel

by Michael Panitz

“Der Fühlungshalter”. U-Boot des Typs VII C, watercolor by Hans-Peter Jürgens[i]

INTRODUCTION: SUBVERTING THE FACE, RECOVERING THE FACE

The face is the gateway to the individuality of the Other. The 20th-century Jewish theologian, Abraham Joshua Heschel, commented on Genesis 1:26, “God said, let us make the human in Our image”, that each human face is distinct from every other, and that this individuality is itself the image of God within humankind. Another 20th-century philosopher, the French-Jewish Emanuel Levinas, has rooted an entire ethical system in the recognition of the metaphysical significance in the face-to-face encounter of two people.[i]

The recognition of the “face of the Other”, i.e., to acknowledge the three-dimensional humanity of the enemy, is challenged by war. All war is dehumanizing. To overcome deeply-rooted inhibitions about taking the life of a fellow human, military training leads the soldier to depersonalize the act of killing. He is conditioned to regard his opponent as a “target”; he “eliminates” the target.

With the mobilization of entire societies on wartime footing that characterized the two World Wars of the 20th century, war has also involved indoctrinating citizens to think of their enemies in impersonal terms. This is most graphically and radically seen in Nazi propaganda films, depicting Jews as rats and vermin. When a society first accepts the depiction of the enemy as vermin, it becomes psychologically possible to use Zyklon-B, originally developed as an insecticide, to perpetrate genocide.[ii]

In democratic societies, as well, the tendency during wartime in the modern era has been to depict the enemy in ways that prepare the audience of those depictions to go into battle and to take lives. In World War II, not only standing armies, but entire nations, stood pitted against each other. The combatant nations conscripted their members on a large-scale. For example, 11 million Americans served in the military during that conflict. Much of the younger cohort of a belligerent nation’s wartime citizenry was likely to be in uniform before the end of the war. Great Britain, with a smaller population and longer span of conflict, called up an even larger percentage to fill its recruitment needs. Moreover, the civilian sector of the society was instrumental in sustaining the morale of the soldier. Civilians corresponded with their relatives and dear ones in uniform. Civilians were called upon “to do their bit”. Many women entered the workforce to fill the places of men in uniform. Men and women, young and old, were exhorted to donate blood and financial assets, to display stoicism in coping with privations and, in England, large-scale homelessness, without losing the political will to carry on the struggle.

Therefore, shaping the mass psychology of the public ultimately had military value. The military encouraged journalists to accompany the troops and write morale-building pieces for civilian consumption, also exercising censorship over words and images that would be transmitted home.[iii]

The technological innovations of modern warfare also contribute to the elimination of the face of the enemy from the consciousness of the soldier. “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes” is advice from the era of the musket, whose lethal range was measured only in tens of meters. In warfare since the mid- 19th century, the rifled barrel was lethal at longer range, and the machine gun mechanized killing.

This depersonalization is especially a feature of naval warfare, where the fighting, albeit carried out by the members of each vessel’s crew, was between ship and ship. Second World War undersea warfare was an extreme example of this. Most of the 50 crewmembers of a U-Boat never saw the ship they had torpedoed, let alone its crew. When attacking on the surface, as U-Boats typically did at night, only the gun crew and the watch-standers saw the action. When submerged, only the captain and those few officers he would invite to the periscope could see their enemy. On the other side, the crews of anti-submarine warfare vessels—patrol boats, trawlers, frigates, corvettes, and destroyers—rarely saw the men of the submarines they fought. An oil slick and some floating debris were the visual evidence of the destruction of the enemy vessel, corroborating the acoustical evidence of a vessel breaking up underwater provided by the surface ship’s hydrophones.

The effort to sustain the will to fight the Second World War involved the genres of fiction as well as journalism. American and British filmmakers produced large numbers of war films, celebrating the exploits of fictional heroes defeating the nation’s foes and presenting models for emulation to stimulate the fighting spirit of the populace.

This essay focuses on one aspect of those war stories: It examines American and British cinematic depictions of one group of German fighters, the officers and men of the Kriegsmarine, during and after the Second World War. Are they seen as “faceless” or as individuals? Contemporaneous depictions of them in stock, impersonal terms are ordinary, and are to be explained by the norms of 1940’s wartime film-making. But even during wartime, several outstanding filmmakers, in one case at the cost of public censure, endowed the German foe with redeeming features,. A closer analysis of these artistic efforts is warranted, with the goal of explicating their exceptional status.

After the end of the war, with the Anglo-American public still eager to relive recent victories, there was a continuing market for Second World War stories and films. In the 1950’s, however, such movies began increasingly to explore differences among the enemy Germans, depicting some as non-Nazi German patriots, and others as closet anti-Nazis. This artistic development also calls for elucidation.

Finally, these two eras of war-story telling have left a legacy for more recent cinematic and television productions, and this essay will offer a brief exploration of the continuing effects of that legacy.

Why focus on Kriegsmarine sailors, and not Luftwaffe aviators or Wehrmacht soldiers? In fact, some American-made films have told stories about those branches of warfare, and the emergence of depictions of differences among Wehrmacht personnel corresponds to the phenomenon discussed in this essay, that the focus on German fighters as individuals grew stronger in post-war film-making.[iv] But the Kriegsmarine merits special attention, because within the navy, the 40,000 man submarine force was composed of freiwillge, volunteers. As such, ideologically-driven Nazis were prominent in that sub-community. Hence, cinematic depictions of U-Boat officers as Nazis are unsurprising, but departures from that norm are all the more worthy of elucidation.

I. The Wartime Years: Ordinary and Extraordinary Depictions

To understand the visual cinematic conventions of World War II naval stories, it is reasonable to begin with wartime documentary film footage. The American documentary series Victory at Sea premiered as a television program in the 1952-1953 season, and was released in theaters in 1954, but it consisted of wartime footage.[v] It covered American naval operations against both Japanese and German adversaries. The relevant footage of German ships and personnel consisted of captured German war photo-journalism. This extended both the perspective and the time-span of the series, allowing the documentary to cover the first two years of the Second World War at sea, prior to the entry of the United States into the conflict.

In that footage, Kriegsmarine personnel are depicted without individuality of personality, but only functional differentiation. Engine stokers, hydroplane operators, torpedo technicians, sonar operators, and officers are all depicted at their battle stations, but no attention is paid to them as individuals.

Understanding why these warriors are depicted without personality thus resolves into two questions: why German wartime journalism chose to do so, and why American editors kept this footage in the final release.

For the Nazi-era German photojournalists, depicting the men as so many cogs in the wheel of the military machine was a positive, not a negative. Nazi ideology hailed the primacy of the state, claiming that the individual found his true nobility not in pursuit of personal goals, but rather in service of Vaterland, Volk and Fuehrer. Nazi ideologues derided the individualism of western society as decadent, and Nazi wartime propaganda predicted the victory of German single-mindedness over the armed forces of their internally-feuding Western enemies.

For the American editors of this captured archival film, the facelessness of the German sailor served as both a sobering reminder and as a validation. On the one hand, Americans acknowledged the efficiency of the German foe, whom they had only defeated after years of maximum effort. On the other hand, seeing the German depicted in depersonalized terms was a confirmation that Americans had fought for a good cause, that of human freedom and individual self-determination.

The archival footage of American sailors also shows them at action stations, but crucially, that is not the only footage of such sailors shown in Victory at Sea. The Americans are also depicted in off-duty moments, enjoying various recreational pastimes. The message is that Americans became warriors of necessity, but remained humans throughout. They never lost their individual faces.

Turning from documentary to fiction films released during the war years, it is important to keep in mind the genre conventions and production conditions of those films. In their numerous war movies, both American and British filmmakers dealt with governmental information ministries and conformed to official guidelines. These guidelines were designed to guarantee that the films would be essentially morale-boosting efforts for the nation at war. The German (and Japanese) enemy in such films is typically depicted in typological and stereotypic terms.

One such film was the 1943 Crash Dive, starring two popular leading men of the era, Tyrone Power and Dana Andrews. The plot is conventional: As its tagline advertising breathlessly announced:

Tyrone Power — Leading a reckless crew on the war’s most

daring mission! Battling death in a depth-bombed submarine!

Blasting Nazis on a bold Commando raid! Finding love in

precious, stolen moments! Crashing his way to unforgettable

glory in…Crash Dive!

The film is a propaganda vehicle, extolling all the types of service within the U.S. Navy. Initially, the protagonist, Lt. Stewart, is seen successfully piloting a small, swift patrol boat in action against a German submarine. Against his preferences, he is transferred to duty as the executive officer of a submarine, Corsair. But ultimately, Stewart learns of the importance of all the branches of the navy, and the film closes with a stirring speech in which he eulogizes each of the different types of warships in the U.S. Navy (except for destroyers—likely an oversight. Hollywood was, after all, a province of civilians.)

Crash Dive follows many of the tropes of wartime American films—brothers in arms, who resolve their inter-personal conflict by teaming up for the greater goal; the heroic self-sacrifice of the “one who didn’t make it”, dying so that his comrades might live; the maturation of the protagonist’s initial brashness into more enduring courage. One such trope, in particular, reassured Americans that they were not being hypocritical in maintaining a racially segregated country while fighting a war against Nazi racism. Although the armed forces were segregated, there were African Americans in specific, secondary roles within the services. These films tend to portray them in a partly-positive, but also partly-condescending, light. The African-American in Crash Dive, Oliver Cromwell Jones, is serving as a steward aboard Corsair. That relatively lowly station was the only one officially open to African Americans in submarine service at the time. When the call is made for volunteers to stage a hazardous commando raid against a German military installation, Jones steps forward unhesitatingly. That is an endorsement of his courage. When asked why he is doing so, he gives a patriotic answer. His character is also given a moment of racially self-conscious levity: seeing his fellow commandos with black paint on their faces to render them inconspicuous at night, he exclaims, “I’m the only born commando here!”[vi]

The German Kriegsmarine officers and sailors in this film, both on the Q-ship that the Corsair sinks and on the base attacked by Corsair’s commando party, are given only two-dimensional portrayals. There is no effort to see them as individuals.

If Crash Dive exemplifies the run-of-the-mill war film, perhaps forgettable today except to film buffs, two other wartime efforts stand out and continue to speak to today’s audiences: Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 49th Parallel and Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat. In each of these, the Germans emerge as fully-realized characters.

Movie poster for 49th Parallel, depicting a party of Kriegsmarine sailors heading ashore in Canada. Source: https://www.filmaffinity.com/en/movieimage.php?imageid=841250554

In 1941, the recently-reorganized British Ministry of Information extended the scope of its activities to include not only documentaries but also feature films made in support of Great Britain’s war effort. Its first project was to underwrite Powell and Pressburger’s 49th Parallel. The title is an oblique reference to the border between Canada and the United States, much of which follows that line of latitude. The story is the saga of six survivors of a German submarine, destroyed in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Canada, who attempt to make their way across Canada to gain refuge in the then-neutral United States. (This was before Dec. 7, 1941, when the Japanese attack upon U.S. naval forces in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, propelled the U.S. into the war.) One by one, they die, leaving only Lt. Hirth, the most ardent Nazi in the group. He actually makes it across the border before being sent back on a clever technicality and subdued.

The filmmakers were eager to contribute their talents to the British war effort. Powell resolved to set the film in Canada, with the United States as the intended destination of the determined Nazis, to bring the Americans into the war on the Allied side. In a later interview about the work, he acknowledged, “I hoped it might scare the pants off the Americans.” Pressburger, a Jewish refugee from Hungary who was working as a scriptwriter in London, also characterized his work as a contribution to the British war effort: “Goebbels considered himself an expert on propaganda, but I thought I’d show him a thing or two.”[vii]

Part of the propaganda value of the film was a bit of military disinformation that it promulgated. The film depicts a fully-operational and comprehensive system of Canadian anti-submarine air defenses. This did in fact not exist at the time of the filming, in 1941. In a later interview, Powell acknowledged the factual inaccuracy, and stated that he suggested the existence of such a fully articulated system in the hopes that it would convince German war planners of the futility of continuing their operations in Canadian home waters.

49th Parallel is noteworthy for its depiction of different personality types among the six U-Boat submariners attempting their escape. While the German protagonist, Leutnant Hirth, is depicted as a rabid Nazi, one of the enlisted men, Vogel, has no ideological ardor. This comes to the fore when the submariners encounter a farming commune of ethnic German Hutterites (a Christian group similar to the Amish). During the time that the submariners spend in the Hutterite community, Hirth attempts to rouse their German racial consciousness, but fails completely. As their leader, Peter, explains, they are motivated by Christian love, not by racial hatred. Vogel, on the other hand, is impressed with their outlook and way of life. A baker by trade, he improves their bakery and delights them by providing them their daily bread, which they acclaim highly, to his great satisfaction. Ultimately, Vogel seeks to defect. He declares to one of the Hutterite women that he is willing to submit to internment as a Prisoner of War, so as to join the commune after the war.

How to account for the sharp difference between Hirth’s and Vogel’s characters, in a British propaganda film? The answer is seen in the fate of Vogel. Sensing Vogel’s ambivalence, Hirth, as his acting superior officer, marches him into the woods, accuses him of treason, pronounces him guilty without even according him the opportunity to speak up in his own defense, and shoots him on the spot.

Powell’s and Pressburger’s message is that there are, indeed, “good Germans”, but that they are not in positions of authority. Under the right conditions, they would be capable of being influenced by the goodness of the people of the Free World. But they do not control Germany; hardened Nazis do. The only way to reclaim Germany into the fellowship of moral nations is to defeat the Nazi leadership. Victory is a precondition for reformation of character.

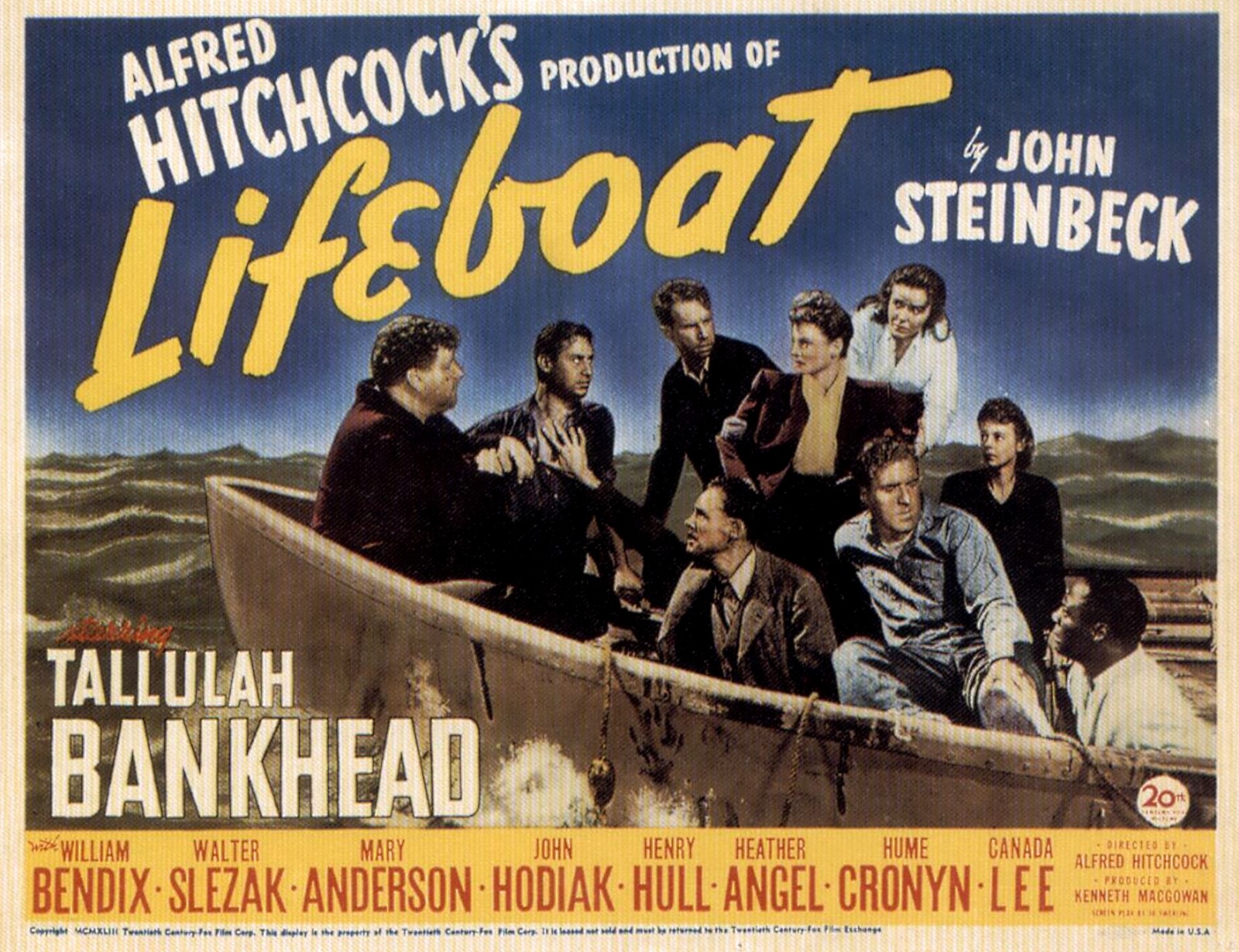

Movie poster for Lifeboat (1944). Source: https://thehitchcockproject.wordpress.com/category/week-29-lifeboat-1944/

Like 49th Parallel, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1944 film, Lifeboat, was occasioned by wartime exigencies. The American Maritime Commission asked Darryl F. Zanuck, head of the Hollywood movie company 20th Century Fox, to make a film about the U-Boat menace to North Atlantic shipping. The request was indeed timely. In early 1943, at the time of this request, the U-Boat offensive was still claiming heavy losses of Allied shipping in the North Atlantic.[viii] Hitchcock was not then working directly for Zanuck, but rather for another film mogul, Robert O. Selznick. But Selznick leased Hitchcock’s services to Zanuck and Lifeboat is the result.

Unlike 49th Parallel, where the characters of Hirth and Vogel represent the extremes, in the work of Alfred Hitchcock, the portrayal of character focuses on the ambivalence and the moral ambiguities that are the common human condition.[ix] This, in turn, affected his portrayal of the U-Boat commander in his 1944 film, Lifeboat.

Nine people find themselves aboard one lifeboat. Eight of them are survivors of a torpedoed merchantman, and the ninth is a German, who feigns being a common seaman but who is soon unmasked as the Kapitän of the submarine, which was itself destroyed in the battle. Over the course of the many days in which they are adrift, without fresh water and with dwindling food supplies, their carefully constructed personas are stripped away and the conflicted inner person emerges. Each one has both good and bad sides to his character. The nurse Alice, for example, initially the exemplification of altruism, proves to have been “the other woman”, engaged in an affair with a married man.

The most problematic member of the ensemble (other than a young German sailor pulled aboard at the very end, as a dramatic echo of the main action), is the German Willi. He insists that the others are setting the wrong course, heading away from Bermuda rather than towards it, as is their intention. When challenged as to why he would help them to take him to Bermuda, when he would simply be a prisoner there, he answers, disarmingly, that he is already a prisoner on the lifeboat, and in Bermuda, at least he would be safe from starvation. But he is seen furtively consulting a hidden compass, and it ultimately becomes clear that he is hoping to take the lifeboat to a rendezvous with his submarine tender.

While initially presenting an inoffensive persona, Willi gradually reveals his true colors. After a storm nearly swamps the lifeboat, Willi takes command. The force of his personality and his physical stamina, coupled with the demoralization and the physical disintegration of the others, allows him to dominate his fellow survivors.

But after he is unmasked as a water hoarder, the fury of the other passengers is such that, led by the nurse Alice (!), they mob him, beat him senseless, and heave him overboard to his death.

Willi is a complex character. On the positive side, he is a cultured man, multi-lingual, knowledgeable of music. A medical doctor before the war, he saves the life of fellow-survivor, Gus Smith, by amputating his gangrenous leg. When rowing the lifeboat, he sings lullabies to the weary passengers. But despite these positives, Willi is ultimately an evil man. He hides his compass from the others and he lies to his fellow passengers about the way to safety, in fact leading them towards capture. He murders Gus, after Gus catches him hoarding water while the others are nearly dying of thirst.

The defining characteristic of Willi is his sense of purpose, in sharp contrast to the fractious internal debates among the other lifeboat passengers, representatives of British and American democracies. Class tensions simmer in the angry relationship of Kovacs, the proletarian from a working class district of Chicago, and Rittenhouse, the fascist-admiring self-made millionaire. The others bicker over who is to take command; Willi simply does so at the opportune moment. He bides his time, plays his cards perfectly, and utilizes the life-threatening danger of a storm to take command just at the moment that the others are too debilitated, emotionally and physically, to challenge him. Only then does he expatiate on the superiority of the German.

Viewed today, it is easy to recognize that Hitchcock intended this film to convey a wartime message: that the Allies needed to unite so as to be able to defeat so well organized an enemy as the totalitarian Nazi society. Filmed in 1943, when the outcome of the war was not yet certain, the characterization of the Nazi as resourceful, cunning, and strong was a call to take seriously the challenge of defeating so able an adversary.

Despite his aims, Hitchcock’s characterization of the German officer Willi as a complex character aroused considerable, even virulent, criticism. The New York Times critic Bosley Crowther observed:

There remains the alarming implication, throughout all the

action of this film, that the most efficient and resourceful

man in this Lifeboat is the Nazi, the man with ‘a plan.’ Nor

is he an altogether repulsive or invidious type. As Walter

Slezak plays him, he is tricky and sometimes brutal, yes,

but he is practical, ingenious and basically courageous in

his lonely resolve. Some of his careful depictions would be

regarded as smart and heroic if they came from an American

in the same spot.

The noted critic and author Dorothy Parker, after whose brash manner the leading character in the film, “Connie Porter” (played by the stage star Talulah Bankhead) was modeled, panned the film with characteristic wit and ruthlessness: She gave it “ten days to get out of town.”[x]

Hitchcock responded to his critics in words that ring true to the reader today. In retrospect, the widespread misinterpretation of his film upon its release is best understood as a reflection of the mass psychology of wartime America. In a 1962 interview with the filmmaker Francois Truffaut, Hitchcock explained his goal in creating Lifeboat:

We wanted to show that at that moment there were two world forces

confronting each other, the democracies and the Nazis, and while the

democracies were completely disorganized, all of the Germans were

clearly headed in the same direction. So here was a statement telling

the democracies to put their differences aside temporarily and to gather

their forces to concentrate on the common enemy, whose strength was

precisely derived from a spirit of unity and of determination.[xi]

With the added perspective of time, it is now clear that Hitchcock was incorporating some positives in his portrayal of Willi so as to portray him as a formidable foe. Defeating him was therefore a greater dramatic achievement.[xii]

Ultimately, Hitchcock passes negative judgment upon the wartime German in general. In the final scene of the film, another German is pulled to safety by the lifeboat passengers, and he immediately pulls a pistol on them. After the African American, Joe, disarms him, but the passengers then allow him to remain on board, the German asks if they are going to kill him. Then, Kovacs, the leading male protagonist, muses,

‘Aren’t you going to kill me?’ What do you do with people like that?

In its own historical setting, the question was rhetorical. The 1944 Anglo-American audience was relied upon to answer, “defeat them”. The individuality of the submarine commander did not yet constitute a change of attitude towards Germany; it was still univocally the enemy to be beaten.

II. Sea-Change in the Cinema of the 1950’s

The seeming exceptions to the norm in wartime films of depicting German sailors in two-dimensional ways, therefore, did not constitute a fundamental reevaluation. Individual Germans were good, but not in control; alternately, Germans had some good points of character, but were ultimately still evil.

In the course of the decade following the conclusion of the war, much was to change, first in life, and then in cinematic art. In the post-war era, relations between the Soviet Union and the Western Powers quickly deteriorated. On February 9, 1946, Josef Stalin defended a new Soviet Five Year Plan, giving priority to rearmament over consumer needs, on the grounds that peace with the capitalist-imperialist powers was impossible. Later that same month, George F. Kennan, the leading U.S. diplomat in Moscow, wrote his famous “long telegram” alerting the State Department to the ways of the Soviets. In March, Winston Churchill, former Prime Minister of Great Britain, delivered his “Iron Curtain” speech in Fulton, Missouri. The “Cold War” had been declared.[xiii]

The Cold War had a profound effect upon the political development of Germany. At war’s end, the four principal victorious allied countries each administered a part of conquered Germany. With the rupture between the Soviet Union and the Western Allies, the United States, Great Britain and France agreed to unite their three sectors. In the new political climate of 1948-1949, The United States and Great Britain gradually developed a willingness for the non-Communist part of Germany to gain independence. This was accomplished by the middle of 1949, with the emergence of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Would this new country be allowed to rearm? That depended on how the Western Allies viewed Germans. In July, 1948, after a massive American airlift broke the Soviet blockade of Berlin, Americans began to feel more positively about their former German foe. Characteristic of this change for the better was the statement of the U.S. Air Force pilot delivering the last of the “Candy Bomber” parcels in “Operation Little Vittles”. Lt. Harry Bachus, who had spent nearly half a year during the Second World War as a Prisoner of War on the outskirts of Moosburg, piloted the B-17 airplane that made this final run, coincidentally, over the same German city where he had been interned. His remarks sum up a remarkable transformation, obliquely acknowledging that Germans had been victims, too, and that American generosity could pave the way for a better German future:

We can show the German people, and particularly these

youngsters, who will be the leaders of tomorrow, that the

airplane can be an instrument of mercy and good will as

well as a machine that can destroy mankind.”[xiv]

The question of a rearmed Germany was bound up in the larger issue of the military preparations of Western nations to counter the prospect of Soviet aggression in Western Europe. In the course of the year of the Soviet blockade, 1948-1949 the Western Allies created the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.[xv] At first mostly a declaration of principles, NATO became a serious military reality in December, 1950, when the American president, Harry S. Truman, appointed General Dwight D. Eisenhower as Supreme Allied Commander of the NATO alliance forces.

Who would fill the ranks of soldiers and sailors, defending Western Europe? All the Western Allies were eager to reduce the strain upon their economies of maintaining large standing armies. What of (West) Germany? Should they shoulder their part of the burden, especially as their country was most likely to be the route of an anticipated invasion?

The British and Americans promoted that step; the French were opposed,. After three years of diplomatic wrangling, in August, 1954, The French National Assembly finally rejected a long-standing proposal to create a European army. The Americans threatened “an agonizing reappraisal” of their commitment to defend Europe.

In this atmosphere of crisis, the British Prime Minister, Anthony Eden, lobbied for the enlargement of NATO to include Germany and Italy. He offered some reassurances to calm French nervousness about a rearmed Germany: Germany would possess no atomic, ballistic, or chemical weapons; there would be no restoration of the German General Staff, and all German forces would be totally integrated under the command and control of the NATO Supreme Commander. Those proposals quickly met with approval by the existing NATO states, and the French, too, yielded. Pierre Mendes-France, the head of the French government, simultaneously removed an obstacle to French-German rapprochement by reaching an agreement with the F.R.G. Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, to return the Saar valley to West Germany.[xvi] The German army and navy were reborn in 1955, now in the service of defending western democracy against Communism.

This new political climate acted as a catalyst for artistic reevaluation. It is possible that, given time, as the passions of the Second World War receded, film makers would have explored the human face of the German enemy because of the dramatic potential of that new approach. But the political realities of the Cold War, including the desire in the USA to see Germany pay towards the cost of defending the West from the Soviet Union, stimulated this change in attitude towards the prospect of a rearmed Germany. That, in turn, showed up even in 1950’s-era films about World War II.

A harbinger of this change is to be seen in one brief moment in the 1953 film The Cruel Sea. That film was based closely upon Nicholas Monsarrat’s novel of that name. The novel, in turn, grew directly out of the author’s wartime experience as a Lieutenant Commander in the British Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, commanding vessels engaged in anti-submarine warfare. Near the end of the film, the British sailors see their first German U-Boat survivors when, having destroyed the submarine, the British rescue the German survivors from the waters of the Atlantic. One officer exclaims to his fellows: They look just like our own! Having spent six years fighting a faceless enemy, suddenly seeing men—and moreover, men in the same half-drowned, diesel oil-smeared condition as the merchant seamen of torpedoed cargo ships whom they have been rescuing from the water—came with revelatory force.

The exploration of the human side of the German Kriegsmarine enemy is given full treatment in three movies that premiered in quick succession in the mid-1950’s: The Sea Chase (1955), The Battle of the River Plate (1956) and The Enemy Below (1957).

The first of these stories, The Sea Chase, is intriguing in that the differences between the historical record and the 1948 novel of that name by Andrew Geer, and between the novel and the film, are all worthy of analysis:

The Norddeutscher Lloyd steamer Erlangen, whose blockade-running exploits were the basis for the Andrew Geer novel and later, the movie, The Sea Chase. Copyright; John H. Marsh Maritime Collection, Iziko Maritime Centre Cape Town.

HMS Newcastle, which intercepted Erlangen outside Montevideo harbor, July 25, 1941. www.wartimememoriesproject.com/ww2/ships/ship.php?pid=77 HMS Newcastle in the Second World War, The Wartime Memories Project.

The history is only partially preserved. The facts as we know them are as follows: The 6100-ton German steamer, Erlangen, built in 1929, and owned by Norddeutscher Lloyd, was in the port of Dunedin, New Zealand, in late August, 1939 under its master, Captain Alfred Grams, with a crew of German officers and Chinese sailors. It left port on the eve of the outbreak of hostilities, Captain Grams having received orders from Berlin to make for a neutral port. The goal was to rescue the ship from being impounded and its German officers from internment as enemy aliens. Erlangen‘s stated sailing plan was to go to Port Kembla on the south- eastern coast of Australia to take on coal. It was known to port authorities that Erlangen had 175 tons of coal in her bunker, insufficient fuel to reach Valparaiso, Chile, the closest neutral port. But Erlangen did not arrive in Port Kembla. Captain Grams had taken her not northwest, to Australia, but south, to the Auckland Islands, to take on food and to cut wood. After the fact, it became clear that he had put into the Auckland Islands’ Carnley Harbor. While hidden there, for over a month, his crew deforested a six-acre region of that island, harvesting wood to burn in his ship’s boilers. The wood of that region was a kind of ironwood, very dense and suitable for use as fuel. On 5 October, 1939, he steamed from his hiding place and arrived in Pierto Mott, Chile, on Nov. 11, 1939, having burned all the harvested wood, as well as the lifeboats and other wooden furnishings on board the ship, and even hoisting sail, all the while successfully eluding British capture. In Chile, he received a friendly welcome from the largely German local population. Grams dismissed the 50 Chinese seamen of the ship’s company, sending them back to Asia, and remained in Chile with 12 German officers, engineers and assistants until mid-1941. Then, German authorities ordered Captain Grams to take Erlangen to the port of Montevideo. His replacement crew was from the German training vessel Priwal. He successfully rounded Cape Horn and entered the Atlantic, but was intercepted by the British naval cruiser HMS Newcastle off the coast of Montevideo on 25 July, 1941, and scuttled his ship to avoid its capture. The Captain and crew were interned for the duration of the war, and freed in 1946.

All this is dramatic enough in its own right, but the 1948 novel changed numerous details, added a love triangle and other conventional plot elements, and supplied characterizations of the captain and key members of his crew, all for the purposes of creating a still-more dramatic tale:

The steamer, renamed Ergenstrasse, was made much older, having been launched in 1896. The ship herself bears the marks of an eventful history—a bloodstain on the floor of the shipmaster’s cabin, where the crew murdered him during the lawless days of the German revolution, October 1918; and a 5-year stint surreptitiously flying the Danish flag, to avoid being given to the French as war spoils. The point of these changes is to make the ship herself partly the heroine of the story. Ergenstrasse emerges as a gallant old lady, listing but full of spirit—in the tradition of sea stories, in which the authors anthropomorphize their vessels.[xvii]

Unlike the historical record, in which Erlangen goes down in the South Atlantic and her captain is arrested, in 1941, in both novel and film, the denouement of the plot is advanced to the end of 1939, and the locale is changed to increase the dramatic effect. Using plywood obtained in Chile, Ehrlich gives Ergenstrasse an altered silhouette and disguises her as a Panamanian freighter. By means of that stratagem, he successfully steams the entire Atlantic from South to North, only to be intercepted off the coast of Norway, on the verge of pulling off a major propaganda coup on behalf of Nazi Germany.

Whatever may have been the character of the real Captain Grams, the novelist gave the fictional captain, Karl Ehrlich, a vivid and unattractive character, essential to the plot of the novel. Ehrlich is a battle-scarred veteran of the German imperial navy, having commanded a German destroyer squadron at the World War I Battle of Jutland. He is hard-driving, “filled with animal energy”, feared by his men. He administers harsh discipline, including physical abuse, but—Hitler-like– is capable of inspiring oratory. Ehrlich’s back story is one of frustration. While in command of a naval stores depot in the chaotic days of late 1918, with revolution and mutiny in the air, he had refused a colleague’s undocumented request for supplies. The colleague rose in the navy and had his revenge; Ehrlich fell out of favor and was discharged; hence his unhappy career as a merchant ship captain. His zeal to return and receive a Kriegsmarine command is his main driving force.

He must get back to Germany… The press would praise him…

They would restore him to his commission… Only in Germany

could he hope to regain his lost rank. All other desires, thoughts,

became subservient to this purpose. He would drive his crew,

kill any or all if he must, but he would see success crown his

enterprise.

Ehrlich is a racist. He fully subscribes to Uebermensch ideology. British women are as unappealing as British food, in his opinion. As for Americans, he dismisses them as a “meteor of nations”, flaring brightly but not for long. Asians are untermenschen. When his crew grumbles about his order to ram a canoe and kill the eight Pacific Islanders on board, he asks his men, already suffering from hunger,

…who has so much food that you’d want to share it with a

yellow-skinned degenerate who, for thirty pieces of silver,

would betray us?

He flatters a German woman whom he is seeking to woo by discoursing on the racial superiority of the Germans, which owes as much to German women as to German men:

In all history, Germany’s is the only nation that’s been able to

come through countless bloody wars without losing its virility…

Only the Germans are able to go on and on, losing their finest in

war but rebuilding an ever sturdier race, physically and mentally,

and, in large part, it’s the German woman who’s responsible.

All of these negatives, except for Ehrlich’s hard-driving nature, disappear in the 1955 movie. The captain, played by the redoubtable John Wayne (who does not even attempt a German accent), is portrayed as a decent and principled, if rough-edged, man of the old school. He is a German patriot, but no Nazi.

This fundamental recasting of Ehrlich’s character is the mainspring for many other changes in the story: The reason for his dismissal from the Kriegsmarine is altered. In the film, it is due to his having expressed anti-Nazi opinions. This necessitates another change: Ehrlich’s reason for wanting to return to Germany is altered to reflect, not personal ambition to serve the Nazi regime, but rather a commendable quality: solicitude for his German crew.

When, at the climax of the film, his ship is intercepted by a British corvette, Ehrlich again shows his true, and non-Nazi, patriotism. He hoists the old, imperial naval flag instead of the Nazi banner and, under that flag, attempts to ram the Britisher. This is a more heroic action than the final encounter in the novel, where Ehrlich is surprised by Lieutenant Napier, the British officer who has been hunting him around the globe. Napier, not commanding a corvette in the novel’s iteration of the story, is instead the leader of an away team based on a small, although armed, fishing trawler. Finding Ergenstrasse off the coast of Norway, Napier uses a boat to board and commandeer her.

At the end of novel, Napier kills Ehrlich. The British officer had tried to arrest him, but Ehrlich rushed him and struggled, remaining on his feet even after absorbing twelve(!) bullets, until he collapsed—an end corresponding to the “animal energy” of the German captain. In the film, we do not see him die. Perhaps he went down with his ship—appropriate enough for a good captain—but the audience is left with the tantalizing possibility that Ehrlich and his lady love interest have escaped together to neutral Norway. In 1950’s Hollywood, amor vincit omnia (“love conquers all”) was the rule.

Other classic 1950’s movie tropes abound in this film: the rehabilitation of a ne’er do well sailor under the stern but fair guidance of the captain; a love triangle in which the captain and the female passenger on board Ergenstrasse, played by the “bombshell” actress Lana Turner, belatedly express their love for each other, and the reformation of character of the passenger herself, at first a Mata Hari type, using her sexuality for German intelligence purposes, but at the end a woman capable of true love.

A conventional movie of that era, especially a John Wayne movie, typically had an unambiguous villain. With Ehrlich no longer available for that role in the 1955 film, the true villain is the First Officer, Kirchner (who had been the Second Officer in the book). In both novel and movie, Kirchner is guilty of murder, but in the film, his character, already bad, absorbs all the evil in the novel’s depiction of Ehrlich. In the film, Kirchner is the vile Nazi.

In sum, the true Nazi in the film version of The Sea Chase remains the villain, but the film has taken a significant step in rehabilitating the German naval officer as a character type. Captain Ehrlich represents the finest traditions of the old, pre-Nazi German navy. He is a German whom Cold War America could imagine as being in command a naval vessel in the newly resurrected German navy—and who wouldn’t trust John Wayne?

The next step in the rehabilitation process was to tell the story of a veteran of the imperial navy and the Weimar Reichsmarine who did serve in Hitler’s Kriegsmarine and yet who could be depicted as a man of honor, an enemy deserving of respect. This was the theme of Powell and Pressburger in their 1956 film, The Battle of the River Plate. That film is a retelling of the first British naval victory of the Second World War, the destruction of the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee.

Movie poster, The Pursuit of the Graf Spee (alternate title of The Battle of the River Plate). Source: www.doctormacro.com/Movie Summaries/B/Battle of the River Plate

The history of the battle, on 13 December, 1939, and the scuttling of his ship by its Captain, Hans Langsdorff, three days later, was widely reported in Great Britain, being the first good news for the British since the start of the war that September. Graf Spee had put to sea shortly before the start of hostilities, and had sunk 50,000 tons of merchant shipping in the Indian and South Atlantic Oceans. The British had sent several groups of warships in pursuit of her, and on 13 December, one such group, consisting of three naval cruisers, found and attacked her. The battleship was more heavily armed than the cruisers, but the British forces attacked from two directions, forcing Graf Spee to divide her fire. Even so, Graf Spee’s gunfire damaged all three of the attackers, one of them, Exeter, severely enough to compel her to retire to the Falkland Islands. But the gunfire from the British ships had done damage too, including one shot from Exeter that destroyed a key component of Graf Spee’s fueling system. Kapitän Langsdorff headed for the port of Montevideo in neutral Uruguay to repair his vessel. He needed more time than the 72 hours granted, however, and, low on ammunition and believing that a large British force had assembled outside the harbor, he scuttled his vessel at the limit of Uruguayan territorial waters, after first having ferried his crew to safety. He subsequently committed suicide in a Montevideo hotel room, lying on his ship’s battle flag and leaving a note reading, in part,

I can now only prove by my death that the fighting services

of the Third Reich are ready to die for the honour of the flag…

In Nazi footage preserved in Victory at Sea, Langsdorff is seen being honored by Hitler on the eve of his 1939 mission. But subsequent events raised the tantalizing possibility that Langsdorff was not a typical Nazi. Perhaps he was, rather, an old-school warrior, a man of honor? The circumstances of his death suggested an air of pre-Nazi chivalry attached to the German officer. His character was further burnished by Langsdorff’s solicitude for the lives of the merchant crews whose ships he had hunted. He brought all the civilian mariners to safety aboard his ship, before sinking their vessels.

Langsdorff had served with distinction in the Imperial Navy, taking part in the Battle of Jutland. and receiving a decoration for his valor. After the First World War, he served the Weimar Republic’s Reichsmarine. When Hitler had taken power, Langsdorff requested sea duty— was he trying to get away from Berlin so as to be farther from the Nazi leadership? Granted, his suicide note contained a declaration of respect for the Fuehrer. He himself was beyond the reach of retribution, but was that intended to protect his family? It was at least possible to see in Langsdorff an echo of an admirable, pre-Nazi military ethos that the British, albeit enemies of the Germans, could respect.

The captain of one of his last merchant ship victims, Philip Dove of the Africa Shell, developed a grudging admiration for Kapitän Langsdorff. After his release, Captain Dove authored a memoir of his experience, I was a Graf Spee’s Prisoner (London, 1940). In his memoir, he recounted numerous acts of kindness and courtesy shown to the prisoners by Captain Langsdorff. When captured, Captain Dove was wearing the short pants of a summer uniform. Knowing that Graf Spee was bound for sub-Antarctic waters for a replenishment rendezvous with her supply ship, Altmark, Kapitän Langsdorff had the ship’s tailor make a woolen uniform for him.

In 1954, Powell and Pressburger, who had continued to collaborate since their 49th Parallel days, were in Argentina attending a film festival. From there, they went to Uruguay to do research for a film on the famous 1939 naval battle, which they judged would make a suitable topic for a commercially successful film. But they were eager to frame the story from a human interest perspective, and when given a copy of Captain Dove’s memoirs, they resolved to use it as the basis for the story. They completed the film in 1955. Dove served as a technical advisor to the film, and another captured merchant ship master, Captain Bernard Lee, played the role of Dove.

Langsdorff’s gentlemanly ways are further highlighted in the film by a contrast with the brutish behavior of other German naval captains. Some of the British prisoners had been held on Altmark and were transferred to Graf Spee during the replenishment. One remarks bitterly on the contrast: now they were being given clean and spacious quarters, but on Altmark they had been confined in a stinking hold. Their conversation is interrupted by a group of German officers and men coming into their room and presenting them with Christmas decorations. Germans and British alike celebrate amiably until the battle alarm sounds and the Germans leave. The lights from the Christmas ornaments allow the British to continue to see even when British gunfire destroys Graf Spee’s lighting system.

By combining the thrill of a naval battle, for which they were allowed to film on actual warships, with the story of growing friendship and respect between Dove and Langsdorff, Powell and Pressurger created a film that succeeded on several levels. The British movie-going public, coping with lingering post-war austerities and the decline of their overseas Empire in real life,[xviii] was eager to relive the historic victories of their nation during its “finest hour”. The Rank Organization, Powell and Pressburger’s corporate backers, decided to hold back the film’s release for one year so that it could be part of the 1956 Royal Film Performance. The film opened to critical acclaim and also garnered high box office receipts.

Cover of 1956 novel, The Enemy Below. Source: dfordoom-movieramblings.blogspot.com/2015/07/the-enemy-below-1957.html

Movie poster from 1957 movie of the same title. Source: dfordoom-movieramblings.blogspot.com/2015/07/the-enemy-below-1957.html

In The Sea Chase, the captain had been cashiered from the German Navy and, while a German patriot, was not serving in a military capacity. In the Battle of the River Plate, the captain was not a submariner, but rather the commander of a battleship. With the U-Boats widely identified in the public consciousness as the main threat to Allied survival, the full transformation in recognizing the human face of the enemy would involve humanizing a German submarine commander. This development took place a year after the release of Powell and Pressburger’s film, in the American movie, The Enemy Below. In that film, the U-Boat captain himself is shown to be a German patriot, weary of war but still willing to defend his country, and decidedly, if carefully, contemptuous of the Nazis.

The Enemy Below was adapted for the screen from a novel by Denys Rainer of the same title. Like Monsarrat, Rayner had spent the war in command of a variety of Royal Navy anti-submarine vessels. Shortly before publishing his novels—The Enemy Below was one of two based on his experiences—Rayner had published Escort, a memoir of his wartime experiences in the Battle of the Atlantic. His first-hand experience is reflected in the details of his novels.[xix]

However, The Enemy Below is a tale of an encounter that seldom happened in actual wartime, the duel of a single submarine with a single anti-submarine surface ship. More commonly, once sufficient warships became available to the Allies, two or more of the escort ships would cooperate in hunting the submarine, the one using its “Asdic” or Sonar underwater acoustical equipment to help guide the other to the submerged U-Boat. As such, the duel of one vessel against another was an apt subject for dramatic treatment in film.

In keeping with the dramatic device of presenting the encounter as a duel, the film establishes a narrative rhythm, going back and forth between the point of view of the German submarine commander, Peter von Stolberg, and the Allied destroyer escort captain, John Murrell. (The film switches the nationality of the Allied vessel from British to American, doubtless for market-driven reasons.)

The reinterpretation of the U-Boat commander’s image, includes lines given to his adversary, the Allied captain. One of the popular conventions of naval tales is that the captain escapes the loneliness of command in conversations with a trusted confidant, the ship’s surgeon. In The Enemy Below, Captain Murrell’s conversations with the doctor are a vehicle for the exposition of the Captain’s back-story, one of personal grief he holds out of view under the surface of his persona as a competent, unruffled commander. These conversations reveal Murrell’s view of life. In one such conversation, where the captain and the doctor muse about what life will be like after the war, Murrell acknowledges that the ultimate enemy below is not only the enemy below the surface of the waves, but rather the enemy below the fragile crust of civilized behavior. Whereas the doctor looks forward to a return to normalcy, the captain is more pessimistic:

Murrell: Yes, but it won’t be the same as it was. We won’t have that feeling of permanency that we had before. We’ve learned a hard truth.

Doctor: How do you mean?

Murrell: That there’s no end to misery and destruction. You cut the head off the snake; it grows another. Cut that one off; you find another. We can’t kill it as it’s something within ourselves. You can call it the enemy if you want to, but it’s part of us. We’re all men.

The inference of this revelation is that Murrell recognizes, in the universal human propensity for evil, a link between himself and his German foe. Later in the same scene, he gives explicit expression to that recognition:

Murrell: I’m just doing what I have to do, like that German captain out there. I don’t like the job but maybe he doesn’t, either.[xx]

Naturally, the film’s main work of reinterpreting the image of the German U-Boat commander is not in oblique inferences from the words of the American captain, but in scenes involving the German commander directly. The Enemy Below focuses even more attention on the character of von Stolberg than had been given to Kapitän Langsdorff in The Battle of the River Plate. The screenwriter, William Mayes, endowed his U-Boat commander with a fully three-dimensional personality.

In an early scene, when the film is still establishing the character of each of its protagonists, Von Stolberg barely conceals his scorn when one of his younger officers, Leutnant Kuntz, displays Nazi ideological fervor. Later, alone with his trusted executive officer, Korvettenkapitän Heine Schwaffer, von Stolberg expresses contempt for the overgrown Hitler-Jugend type of zealot sent to his crew. This scene merits close analysis:

(Setting: The command area of the U-Boat)

Von Stolberg (toweling himself off after having been topside in the foul weather): Whose watch is next?

Von Holem (a subordinate officer): Leutnant Kuntz, Herr Kapitän.

Von Stolberg (over intercom): Leutnant Kuntz report forward.

(Von Stolberg looks up and sees a sign posted on an overhead bar. He looks surprised and displeased. The sign reads, “Fuehrer befiehl und wir folgen”—The Fuehrer commands and we follow.” Apparently, it has just been put in place by Kuntz, the ardent Nazi.)

Kuntz: You wanted me Herr Kapitän?

Von Stolberg: Yours is the next watch topside. We have a signal on the FMB. I think it’s a false echo. But to check its reaction you will zigzag twice an hour until daybreak. If it moves in closer, you will awaken me immediately.

Kuntz: Jawohl Herr Kapitän! (salutes)

As von Stolberg walks off, he passes the newly-posted sign. Von Stolberg’s body language (he is seen from behind) suggests irritation, and he throws his towel over the word Fuehrer, as if to efface it. Then he goes into his cabin and invites his executive officer to join him.

Von Stolberg: Schwaffer!

Schwaffer: Mm?

Von Stolberg: Come in Heini. (Schwaffer enters)

Von Stolberg: Ah, that Kuntz annoys me. Remind him that we do not salute at sea.

Schwaffer: He’s new here, Herr Kapitän. He will tire of it.

Von Stolberg: He’s new… like our new Germany: a machine.

Schwaffer (looking a bit uncomfortable): Herr Kapitän, do you think we are wise in risking that image to be a false echo?

Von Stolberg (pouring a drink): Wise? Expedient. Time is important, and we would travel too slowly under water. In 48 hours we rendezvous with Raider M. We take the captured British code book and we go home with it. And this is the important thing. Not the code book. But because when we have it, we can go home. (He lifts his glass in a toast) Auf dein Wohl (drains his drink).

Schwaffer (drinking with him): Zum Wohl, Herr Kapitän.

Von Stolberg (making a face) Tastes like oil and bilge and green mold. Sit down Heini. Tastes like a U boat. I’ve been in the U boats too long. There was a time I went to sea with a fresh heart. But that was many years ago. Now I can only thing of going home. (Offers another drink) You want more?

Schwaffer (Covering his glass in a polite gesture of refusal) No more, Herr Kapitän.

Von Stolberg: You think I take too much. Just enough to sleep. I cannot rest without it. I think too much. (Raises his glass in a toast) Never think, Heini. Be a good warrior, Heini, and never think. You pay a penalty for thinking. You cannot rest. (Drains his glass, puts it down, and takes a framed photograph from his shelf.) I taught these sons of mine to be good warriors. Country, duty, ask no questions. (Shows Heini the photograph.) One of them is at the bottom of the sea, this one is a cinder in a burned airplane. And I am glad, that is the way for warriors to die, young and with faith. I have lived too long…

We’re friends, Heini?

Schwaffer (looking non-plussed): I’ve been with you since I was a cadet.

Von Stolberg: That’s not what I asked you.

Schwaffer: I do not know. Sometimes I’m afraid of you. Many times I do not understand you. I’m not certain we are friends.

Von Stolberg (animatedly): We are friends. Believe that. We are friends. Because we are friends, I tell you something: (lowers his voice) I’m sick of this war. It’s not a good war. You don’t remember the first one. I was a Faehnrich in the U-boats and, oh, how proud I was! We went out in those little sardine tins, and if we submerged, we couldn’t always be sure we’d come up again. Oh it was a good game we played. The captain would look through his periscope and sight a target , and then he did arithmetic in his head and said, “Torpedo los”! And you know something: sometimes the torpedo wouldn’t even leave the tube! And if it did, we were most lucky to hit something. And now, I look in the periscope and it gives me the distance and the speed. I pass this information to the attack table. The machinery turns, the lights flash, and we get the answer. The torpedo runs to its target. And there’s no human error in this. They’ve taken human error out of war, Heini. They’ve taken the human out of war. (pause)

War was different then. It put iron in the country’s backbone. It gave the brave memory, and even in defeat, it gave them honor. But there is no honor in this war. The memories will be ugly, even if we win. And if we die, we die without God. Do you know that, Heini?

Schwaffen: (after a beat) I listen to what you say, Herr Kapitän.

Von Stolberg: (lying down on his bunk): It’s a bad war. Its reason is twisted. Its purpose is dark. It’s not for a simple man.

(Von Stolberg closes his eyes. Schwaffen ponders for a moment, then gets up and covers the sleeping captain with his blanket, turns off the light, leaves and closes the curtain behind him.)[xxi]

This scene encapsulates the difference between a wartime depiction of a German Kriegsmarine officer and the new approach of the 1950’s:

- Von Stolberg is war-weary, more excited about going home than about fighting.

- He is disillusioned. It is dangerous to think in these dark times.

- He himself criticizes the “New Germany” in terms that could have been borrowed from Allied discourse: The New Germany is dehumanizing. It is soul-less. It has not given Germans a good cause for which to fight.

- He himself contradicts the assertion of the German army belt buckle, “Gott mit uns”. The so-called New Germany has alienated itself from God. Death is so close; and allegiance to Hitler has put Germany on the course of damnation, dying without God’s consoling presence.

This last point, especially, suggests the American milieu of the 1950’s. Americans of that decade were a very church-going people. They identified religious loyalty with the cause of freedom. True, Franklin D. Roosevelt had already identified Religious Freedom as a key component of the American vision, as far back as his 1941 “Four Freedoms” speech. But in the 1950’s, American theism took on new connotation, thanks to the Cold War. Following classic Marxist critique of religion, the Soviets proudly proclaimed their atheism. In 1954, acceding to President Eisenhower’s request, the American Congress added the phrase “Under God” to its Pledge of Allegiance. While the American Supreme Court safeguarded the right of American citizens to practice no religion, in the popular eye, to be an American was practically synonymous with being a believer.[xxii]

In the film’s final scene, Von Stolberg’s religiosity again comes to the fore. The German submariners are, at this point, all prisoners on an American vessel, but they are being well treated and have been given fresh clothing. They are standing at attention at the rail of the ship, prepared to perform a burial at sea for their dead Executive Officer, whose shrouded body is lying on a plank. As the men sing the traditional warrior’s bereavement song, “Ich hatt’ einen Kameraden”, the Kapitän recites the religious liturgy of committal. Unlike so many films, which curtail the time devoted to religious ceremonial, The Enemy Below presents the full liturgy. Von Stolberg intones the traditional formula for his deceased friend with gravity, infused with sincerity:

(von Stolberg) Nachdem es Gott, dem Allmächtigen, nach seinem unerforschlichen Ratschluss gefallen hat, unser Kameraden Heini Schwaffer für sein Vaterland sterben zu lassen und nach einem Leben voll Treu und Plifchterfüllung in sein himmlisches Vaterhaus aufzunehmen, ist es unsere traurige Pflicht, den geliebten Kameraden hier auf hoher See den Wogen des Meers zu übergeben.

It bears emphasis that the film’s characterization of Kapitän von Stolberg is considerably altered from that in Rayner’s novel. In that earlier iteration of the story, the submarine commander is an aristocratic Prussian Junker. He is disrespectful of Nazis because they are low-born, socio-economically; but he does not express opposition to Nazi ideology. At one point in the shifting game of hunter and hunted, he indulges in ethnic stereotyping, opining that his Germanic thoroughness can be counted on to defeat the intelligent improvisations of his British adversary.

Nowhere are the divergences from novel to film more blatant than in the ending of the story. In the novel, after both dueling captains have succeeded in sinking the other’s warship, they find themselves in the same lifeboat. But the conflict continues. Von Stolberg erroneously thinks that the German surface ship with whom he was about to rendezvous is the closest combatant, and that within a short time, all the British will be prisoners. He addresses the British captain as such. But in this instance, Captain, Murrell has out- thought him. Murrell has correctly inferred what the submarine was up to and has signaled his own command as to the likely coordinates of the German surface vessel. At the moment that von Stolberg claims the British as his prisoners, British vessels are sinking the German raider. While that is happening, over the horizon, the British and German crews fight it out using fists and makeshift clubs until a British vessel comes into view, settling the matter as a victory for the British side.

In the film iteration of the story, the relationship could not be more different. Near the end of the encounter, each of the combatant’s ships is sinking and both crews have abandoned their respective ships. The Americans, already in lifeboats, are rescuing the swimming German submariners, helping them aboard. The only men remaining on board their vessels are the two captains and the badly wounded German Executive Officer, Schwaffer. Von Stolberg pulls Schwaffer to safety, leading him out of the submarine onto its conning tower.

There, for the first time, von Stolberg sees Murrell, standing on the bridge of his own burning and sinking vessel. Each captain has previously been depicted as wondering about the other, trying to get into the other’s mind, and now they belatedly see each other. What emotions will they show? The movie focuses on this first face to face, encounter. Von Stolberg looks at Murrell for a long minute, recognizing that he is facing his dueling opponent, and, with a meaningful expression, he offers him a salute. Morrell returns the salute with great respect. They have truly seen each other’s faces.

The sympathy thus engendered leads Murrell, at great personal risk, to remain on his burning bridge, fetch a rope, and throw it to von Stolberg. The two captains cooperate to save Schwaffer, and then von Stolberg climbs the rope to Murrell’s bridge. Likewise braving danger, since the submarine is rigged to explode momentarily, the Americans guide their lifeboat back to their vessel and rescue all three of the officers.

True to the framing of the combat as a personal duel between the two captains, the final moments of the film, after the conclusion of Schwaffer’s burial at sea, are a time of connection for Murrell and Von Stolberg. Murrell walks up to Von Stolberg, who is standing at the fantail of the ship and looking out at the ocean. He offers him a cigarette, which von Stolberg accepts. Murrell lends von Stolberg his own lit cigarette to use in lighting the one he has proffered. Then they speak:

Von Stolberg: I should have died many times, Captain, but I continue to survive, somehow. This time it was your fault. (smiling ruefully)

Murrell: I didn’t know. Next time, I won’t throw you the rope.

Von Stolberg hands back the cigarette, and shakes hands with Murrell. “I think you will.”

Both smile faintly and turn to face the foaming wake.[xxiii]

This final note is one of improbable but definite camaraderie—suitable for the America of 1957, ready to embrace the “Good German” as a brother in arms against the Communist menace.

How true to history is this 1950’s presentation of a U-Boat captain? While after the war, surviving German veterans were eager to portray themselves as non-Nazi, that defense rings hollow with respect to captains of U-Boats.

Most of the captains, unlike the cinematic von Stolberg, were young men, perhaps in their late 20’s or early 30’s. Their period of character formation was during the Nazi era, not before. Moreover, the U-Boat arm as a whole expanded rapidly during the war. Only 57 submarines were in the Kriegsmarine at the start of the war. During the war, many hundreds were built and launched. There were not enough pre-Nazi Reichsmarine veterans to be more than a small percentage of the 40,000 men of the submarine force.

A measure of the fervor of the U-Boat crews is their condition, and the condition of their vessels, at the end of the war. In his historical memoir, Raynor reported that his command was given charge of two captured U-Boats at the end of the hostilities. The Germans serving aboard had clearly not given up the fight:

The two U-Boats that surrendered in the Portsmouth command

were in excellent condition, outside and within. Morale was

good and their crews waited only for the new boats. They may

have hoped that if the war had gone another six months they

would prove the saviours of the nation. Such hopes of course

were nonsensical. Germany was utterly defeated.[xxiv]

Still more ardent were the two submarine commanders[xxv] who ignored the surrender order and accomplished an arduous trans-Atlantic crossing, much of it underwater, to arrive in a hopefully-friendly right-wing Argentina. The U-530 under Oberleutnant Otto Wermuth arrived in Mar del Plata, Argentina, in July, 1945, and surrendered there. Heinz Schaeffer, commanding the U-977, held out still longer. He only reached Argentina on August 17, 1945, three months after the Nazi Reich had come to an end. In his memoirs, published seven years after the war, Schaeffer (of course) denied having been a Nazi. But he also explained that he took the boat and those of its crew who were willing to accompany him because he was fearful of returning to an Allied-administered, “Morgenthaued” Germany. This is a reference to the propagandist claim of Josef Goebbels about a prominent Jewish member of the Roosevelt administration, Henry Morgenthau, Jr. Attempting to sustain the flagging zeal of the German military, Goebbels threatened that if America were allowed to conquer Germany, Morgenthau’s plan would result in the destruction of all German cities, the reduction of Germany to pastureland, and the castrating of German males. For Schaeffer to have believed this fanciful propaganda suggests that he was more ideologically inflamed than he later claimed.[xxvi]

In sum, most of the U-boat captains, post-war revisionism notwithstanding, were likely to have been hard-core Nazis. The film depictions analyzed here are significant, not as illustrations of the history of the Second World War, but rather as reflections of American and British anxieties and aspirations in the decade that followed.[xxvii]

III. Echoes of Earlier Eras

In the six decades since the release of The Enemy Below, there have been relatively few Anglo-America cinematic depictions of Kriegsmarine personnel. The most important new chapter in the imaginative recreation of the world of the U-Boat was not a British or American production, bur rather the German film, Das Boot.

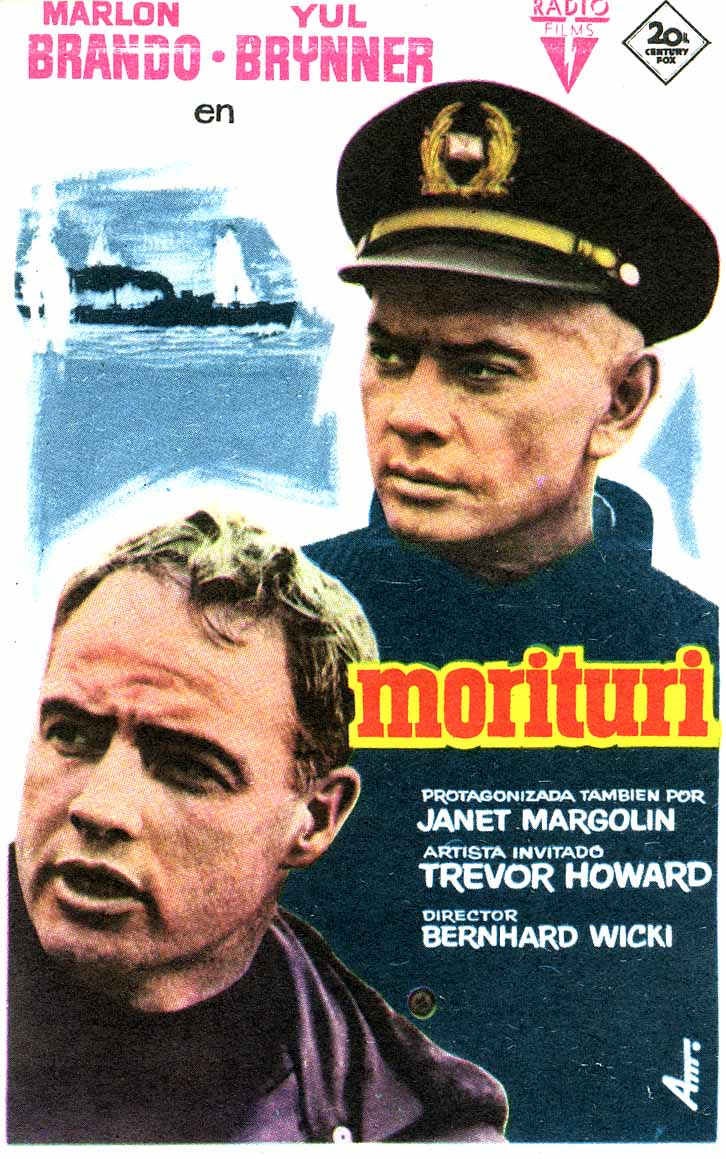

Two American films are (at least partially) within the scope of this essay. For its 1965 film, Morituri, (also known as The Saboteur: Code Name Morituri) Twentieth Century Fox engaged an Austrian expatriate, Bernhard Wicki, as director. Wicki had been imprisoned in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1939 for his membership in an anti-Nazi youth group. After his release, he relocated to neutral Switzerland.

Morituri is reminiscent of The Sea Chase. Like the 1955 film, it featured a patriotic German merchant ship captain, Captain Mueller, portrayed by Yul Brynner, who has suffered career setbacks on account of his forthright anti-Nazism. Again, as in the earlier film, the villain is the first officer, an ardent Nazi . Adding to the dramatic mix is the protagonist of the film, portrayed by Marlon Brando. His character, Robert Crain, is a pacifist German expatriate living in India who is pressured by the British into booking passage on the ship and helping the Allies to capture it. The ship is carrying a cargo of rubber, badly needed by all sides for their war effort. The main dramatic conflict is between Mueller, who would scuttle the ship rather than allow it to fall into Allied hands, and Crain, who plots to prevent the scuttling. At the end of the film, Crain convinces Mueller to allow his damaged ship to be rescued by the Allies.

Evidence of the film’s 1960’s provenance is the role of “Esther”, a German-Jewish woman played by Janet Margolin. Esther is a passenger aboard the merchant ship. When Captain Mueller allows her the use of his cabin, she accuses him of wanting to take advantage of her sexually. She assumes that, as a German, he would share in the racist Antisemitism of the Nazis. He rejects her accusation brusquely, asserting that it ought not be incredible that he regards her as simply a fellow human. Esther’s anger is explained in the course of the film by the revelation of her back-story. She had been sexually abused by the Nazis. As the plot progresses, she is also the object of lecherous affections by several members of the mutinous crew aboard Captain Mueller’s ship. The incipient sexual openness of films, increasing throughout the 1960’s, is reflected here, as is the higher public consciousness of the Holocaust, brought forcibly to the world’s attention in 1961 with the Israeli apprehension and trial of Adoph Eichmann.

Critics hailed the performances of Brando and Brynner, but criticized the pacing and plotting of the story. Ultimately, Morituri has sunk into near-obscurity.

For the purposes of this essay, it is noteworthy that Morituri is evidence that the dramatic device of making the “Good German” the captain, and the true Nazi, his subordinate, a novelty in the 1950’s, had become a trope by the next decade.

Movie Still from U-571, depicting the American crew, in German uniforms, enduring a depth charge attack in their captured U-571. Source: www.mediacircus.net/u571.html

In 2000, a French-American consortium developed a story by Jonathan Mostow into a technologically flashy, but conceptually old-fashioned, U-boat movie, U-571. The story is loosely based on several British and American naval exploits in the Battle of the Atlantic, recovering the secret German Enigma encoding machine from U-boats. In the film U-571, the Americans have located a damaged U-boat awaiting a rendezvous with its tender. The Americans quickly re-configure one of their submarines to look like a U-Boat, put out from Norfolk, Virginia, and reach the stricken sub just before its German tender arrives on the scene. An away party of Americans successfully defeats the U-Boat crew and collects the Enigma, but then, the German ship, having arrived, destroys the American submarine. The few members of the away party are forced to take cover in the U-boat, quickly learn how to operate it, repair its considerable damage, and fend off an attack from a German destroyer. Of course, they do all of that.

One of the characters of U-571, of great importance for the unfolding of the plot, is the commander of the German submarine. He is captured and ferried over to the American submarine, but when the American boat is destroyed, he survives and swims back to U-571. He is brought aboard and masquerades as a common electrician. On board the commandeered submarine, he does his best to subvert the Americans, twice nearly accomplishing the destruction of the boat, before one of the Americans kills him. The commander could have come from Lifeboat. He is able, devious, resourceful, a formidable and implacable foe. The only alternatives are to kill him or be killed by him.

Critics pointed out similarities between U-571 and other submarine films, such as The Cruel Sea and The Crimson Tide. It is, indeed, closely genre-bound. Among the films surveyed in this essay, U-571 is most reminiscent of Crash Dive. As in the 1943 film, the protagonist is an Executive Officer, who learns in the course of the story how to step up to the higher level of command. As in Crash Dive, U-571 contains a poignant scene in which one crewmember sacrifices his life to save all the others. Again, the later film highlights the patriotism of the one African-American serving in the crew. As befits a film made after the Civil Rights movement transformed American consciousness, though, the African American cook in the later film, portrayed by T. C. Carson, refers to his color seriously rather than jokingly. He taunts a captured Nazi submariner: “It’s your first time looking at a black man, ain’t it? Get used to it!”

In addition to the slightly additional prominence given to the African American crew member in U-571, as compared to Crash Dive, another nod to the turn of the century provenance of the film is in the scenes involving the Executive Officer and the Chief Petty Officer. The navy is a strongly hierarchical organization, but American democracy is more egalitarian. In practice, this can lead to an interesting dynamic in the relationship of an officer to a chief petty officer, who is not a commissioned officer but rather a high-ranking enlisted man. The Chief Petty Officer Klough, played by the veteran actor Harvey Keitel, knows both his men and his boats. In a key scene, after Lieutenant Tyler, played by Matthew McConaughey, confesses that he does not know the solution to the existential problem facing the away team in its commandeered U-Boat, Klough gives Tyler a valuable “pep talk”. Finding a private place to talk, he first he asks for, and receives, permission to speak frankly. Then he explains that the persona of confidence is vital in a commander, even if he is internally unsure, because only that persona will keep the crew from disintegrating. Tyler learns the lesson, and his confidence is what allows him to rescue his crew, defeat the German destroyer pursuing them, and fulfill his mission.

Now, the wisdom of a rookie officer taking good advice from a seasoned “non-com” is nothing new, but it was not a feature of the older films surveyed here. Its appearance in a film of this genre points to the increased individualism in American society after the traumas of Vietnam and Watergate.

The film also offers a compliment to the German foe that was not a feature of earlier films. At one point, Tyler orders Klough to take the boat deeper than any American boat had dived. Every submariner knows that with increased depth, the water pressure on the boat’s hull grows exponentially. After a certain point, the hull will fracture and everyone aboard will drown. Klough plainly doubts the wisdom of the order, but he obeys it, and the U-Boat, built to dive deeper than any of the American submarines of that era, survives. Klough offers a positive assessment of German engineering: “Man, those Krauts sure know how to build a boat!”

Critics hailed the film’s strong script and applauded its technical effects. But British critics, and the British public in general, took heated exception to the film’s implicit claim that the capture of the Enigma machine was an American accomplishment. In historical fact, the British had done so first. HMS Gleaner captured three rotors of an Enigma machine from one of the crewmembers of U-33 off the coast of Scotland in 1940, In May, 1941, HMS Bulldog recovered an entire machine, plus valuable codebooks, from U-110. Later in 1941, the British also captured U-570 and recovered another one of the machines. When the Americans seized an Enigma on board U-505, captured in 1944, the machine was no longer the item of principal military value, but rather its accompanying codebooks. The American film did pay tribute to the British achievement in an end-title, but that was too little and too late to satisfy the critics.[xxviii]

As if this evidence were needed: U-571 serves as an additional cautionary tale that Hollywood and history have a loose friendship. Feature films are a form of commercial entertainment, and are marketed with entertainment values paramount. These films, even those that are historical dramas, are not committed to historical accuracy. They do have some historical value. But often, insights about the people making the films, their perspectives, and the times that shape them, are the most valuable historical lessons to be gleaned from “history-inspired” films. That is, after all, the principal thesis of this essay.

IV. Epilogue: Can an Alien Enemy have a “Human Face”?

The theme of “seeing the face of the enemy” appears in science fiction settings, too. That is of course, a different genre than the war story, but one particular science fiction work for television merits attention here, because it is closely related to one of the films discussed in this essay.