Apr 13 2024

From Time to Time: Turning a curse into blessings. The Bernheims after Passau in Cape Town and San Francisco (Part 2 of 2)

by Anna Rosmus

Anna Rosmus uses archival material and interviews to follow the paths of former Passau residents. Quotes not cited are from her conversations and correspondence.

This piece is the second of two on the Bernheim family of Passau. Read the first stage of their story in Passau here.

Temporary exile in and from the Saar Basin

Felix Bernheim, who had fled to his sister Helene in Saarbrücken in 1933, barely managed to hang on to life. His son, Anthony Bernheim, recalls that he made a living “by providing character descriptions based on handwriting, and fortune telling based on tea leaves on the bottom of [a] tea cup.”

After January 13, 1935, when more than 90% of the Saarland electorate voted for reunification with National Socialist (NS) Germany, thousands of German expatriates and other political targets fled to France. Among them were Helene Wertheimer and her family. At first, they moved to Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, in the northeast. After World War I, France had been relatively open for Jewish immigrants. The passports of Alfred and Bertha Bernheim were confiscated, however. On December 10, 1935, the couple returned to Buchau.

On June, 28, 1939, they joined Helene and her family. At that time, after a significant increase of refugees from NS-Germany and the Spanish Civil War, immigration was strictly limited, and internment and detention camps for refugees spread terror.

In the spring of 1940, when Germans invaded the Third Republic, less than half of its approximately 350,000 Jews were French citizens. According to an armistice agreement, signed on June 22, Germany occupied northern France and the entire Atlantic coastline, down to the border with Spain. The newly established Vichy government in the South cooperated with Germany. The so-called “Statut des Juifs” (Jewish Statute), passed in October 1940 resp. June 1941, excluded Jews not only from public life, but it removed them from civil service and the military as well as from commerce and professions such as medicine, law, and education.

Life for Helene Wertheimer and her family was rough. After she managed to have both parents released from an internment camp, all five moved to southwestern France. As foreign nationals, they were assigned to live in the village of Castelmaurou, near Toulouse, where they arrived on December 20, 1940.[1] Marie Clauzolles, née Laurens, widow of Joseph Clauzolles, owned a rural estate and a vineyard. She recalled leasing one room and a very small kitchen to them.[2] Leaving the village was not permitted. In 1942, persecution and arrests began. When Lutz did not report for forced labor on September 1943, he went “underground” in a different province. Helene and her daughter hid in a very small building on the remote vineyard, that lacked even basics such as electricity and a toilet.[3] From May, 9 until July 31, 1944, SS and other German forces occupied the village. Three weeks later, Toulouse was liberated.[4]

Starting Over in South Africa

South Africa, then a British Colony, differed somewhat. While some Jews may have been among its early settlers, a steady flow of Jewish immigrants from Europe did not arrive until the British occupied the Cape in 1806. For many years, Cape Town remained the main center of Jewish life in South Africa. From 1933 until 1935, Louis Gradner, a Jew from Poland, was actually mayor of Cape Town.[5]

At that time, South Africa’s immigration policy towards Jews from Western Europe was relatively lenient. Once a passport and an affidavit, signed by a South African citizen, were submitted to the immigration authorities, Jews were free to enter the country.

Its society, however, was not only colonial and racially deeply divided, but many Afrikaners sympathized with the Third Reich, and organizations such as the “Grayshirts” and the “Ossewabrandwag” were openly anti-Semitic. The Quota Act of 1930 intended to curb the arrival of Jews.

In May 1933, the country’s Jewish community created the South Africa Fund for German Jewry. It helped refugees find jobs as well as accommodations. Assistance like that was essential, especially after September 1934, when Jews were no longer permitted to take more than RM 10 out of Germany.[6] In April 1935, Felix Bernheim boarded a refugee ship, possibly in Marseilles. On the 17th, he arrived in Cape Town, and before long, he started a business, selling ground coffee.

In September 1936, when South Africa announced that starting in November, each immigrant would have to deposit £100 pounds, instead of an affidavit, various organizations rushed to charter a boat. On October 8, the SS Stuttgart set sail, with 537 passengers on board. At the end of October, just before they docked, dramatic protests erupted.[7] Among the protestors were Professor Hendrik Verwoerd, the apartheid architect, and Daniel Malan, who would become the first prime minister of that regime in 1948. The latter boldly claimed to act in the best interests of Jews, because the potential for conflict would rise, when their population would increase too much.

In 1937, the so-called Aliens Act further restricted German-Jewish immigration. Else Kirstein and her daughter Margot, Bernheim’s Deggendorf cousins, were among the lucky ones. Tim Rudnick, a son of accountant Maurice Rudnick, wrote on March 8, 2021:

My mother, Margot, and Elsie reached Cape Town on a Union-Castle Liner in 1937, and were sent to Southern Rhodesia. I am not sure when the remainder of the family arrived, but it included Max and Martha Stern, Herbert, their son in law, and his mother. As Germans, they were treated well, but had to obey a parole order, report to the police station on a regular basis until the end of the war.

As soon as World War II started, the South African Holocaust and Genocide Foundation (SAHGF) pledged that the “Jewish community would do everything in its power to assist the Union and its allies in the fight for victory.”[8] It raised funds, and it encouraged Jews to join the Union Defense Forces. By January 1943 8,366 Jewish men and 542 Jewish women had enlisted.[9]

Felix Bernheim was one of them. When he and his business partner could no longer obtain fresh coffee beans, they substituted chicory. On January 6, 1943, in accordance with the British Nationality in the Union and Naturalization and Status of Aliens Act from 1926, Felix was naturalized as a South African citizen.[10]

When Felix began his service in a South African unit of the British Air Force, his business partner took control of their coffee business. According to his son, Anthony Bernheim, however, Felix recalled that his partner seized “all the assets, leaving Felix nothing when he returned from his military service.” That meant, Felix had to start all over again. This time, as a citizen, at least he could utilize his Passau experience by opening “Felicity Stores”, a clothing enterprise.

On Friday, March 23, 1951, Felix Bernheim celebrated his 45th birthday. At 10:15 AM, at the Claremont Synagogue of Cape Town, he married Natalie Miriam Greene from Birmingham in the United Kingdom. After the ceremony, Dorothy and Maurice Blair, Miriam’s sister and brother-in-law, hosted an 11:00 AM reception at their home on “L’Avenir,” Avenue De Mist, Rondebosch, Cape Town.

Anthony Nicholas Bernheim was born in 1952. He grew up in Cape Town, and recalled on March 14, 2021:

Until I was about 11 or 12 years old, I have no memory of my parents ever setting foot in a synagogue or discussing religion. However, they brought in a tree every year at Christmas time. I did know that I was Jewish but did not know much more than that. We lived in a working class neighborhood, where only one other family was Jewish. I first experienced discrimination, from the neighborhood children because of being Jewish. Occasionally, my parents were invited to a Seder at Passover, and I have vague memories of attending two Seders (most likely Orthodox) at homes of family friends. When I turned 11, my parents decided that I needed to have a Bar Mitzvah. The only synagogue close by at that time was the Rondebosch Orthodox Synagogue, so that is where it was held on September 18, 1965. My parents hired an Orthodox Israeli teacher to prepare me for the Bar Mitzvah services.

Thereafter, an American Rabbi arrived in South Africa and founded the Reform congregation in Cape Town, where my mother started to attend the services (with me) for the High Holy Days. My parents did not get actively involved in the Jewish Community, and we did not have any religious symbols in our home. It seemed to me that my father was more focused on the survival of his business than on religion or the cultural traditions that are practiced by secular Jews.

Tim Rudnick recalled on March 8, 2021:

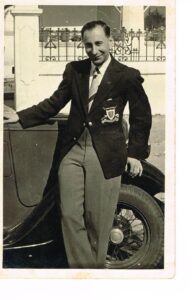

My dad worked for a group of accountants, and one of the clients he was assigned to was Felix Bernheim. They did get to know each other well. Felix liked old cars, and my dad recalls a photo of him in a rare car, called a Spider, together with a member of the Moos family in the Netherlands, while on holiday there.

In 1952, my dad moved to Bulawayo, in what was then Southern Rhodesia, to progress his career, as the economy there was strong. Although he briefly returned to Cape Town, he emigrated to Bulawayo permanently in 1957.

And there, Maurice Rudnick met Margot Kirstein. The couple married on November 11, 1959, in the progressive Bulawayo Synagogue. Anthony Bernheim remembers a trip to Southern Rhodesia, in 1960. It was a family visit. Photos show the former Deggendorf cousins together.

On March 14, 2021 Anthony stated:

Growing up in Cape Town was hard for me. There was not only discrimination because we were Jewish, but also because we lived in a working class community.

When I was quite young (8-11 years old), my father attempted to tell me war stories from his time in the military. My mother shut that down quite quickly. No real or meaningful discussion about the war or Holocaust was allowed, although I did know that I was Jewish, and that my father had fled Germany because he was Jewish. Nor did they have many friends in Cape Town. The parents of some of my friends became their friends.

My immigrant parents did not have many friends in Cape Town. The parents of some of my friends became their friends.

My mother’s sister lived in Johannesburg. She had two daughters and one son. That family came to my Bar Mitzvah, but one daughter did not attend. In fact, she had fled South Africa. (That story is in a book The Song Remembers When by Hilary Claire). No one spoke about why my cousin Hilary had fled the country (at least in my presence). However, I found out later that she and her husband were working in a cell for the African National Congress. In a very simple way at that time, I began to connect my understanding of the Holocaust with my understanding of apartheid. So began my questioning of apartheid, and at 13 years old, I decided that I needed to leave South Africa.

Whereas others may have caved in, acceded to local demands, Anthony Bernheim doggedly pursued his path. He admitted,

Going to school and to university in Cape Town were not the best years of my life. I did not receive much support from my school teachers, nor at the university. Two professors connected with me in particular ways. One, possibly at a risk, spent some time during our private meetings helping me to better understand the political situation in South Africa, and another occasionally invited me to his home, where I got to know his family. (There was always a concern at the university that someone in each class might be an informer for the South African security police, so I was quite careful with friendships.)

Starting in December 1972, the end of my second year at Architecture School at the University of Cape Town, and during summer break in the southern hemisphere, I decided to take a three-month trip to Europe with a friend. My goal was to start in England, travel through Europe, and end up in Israel, meet with family members (many of whom I had not previously met), and to research countries/cities that could become my future home. We met Janis[[11]] in Florence, Italy, and spent some time together in Athens, Greece.

Architecture School requirements included working in an architect’s office and traveling to see buildings. In 1974, I obtained a position in an architect’s office in London for most of the year, and visited Janis in the San Francisco Bay area for about three months, returning to Cape Town in February 1975. That was when I decided to make the San Francisco Bay Area in the U.S. my future home. During that visit I also started to make contacts in my own field of Architecture and Planning.

I had always been interested in the social aspects of architecture. As an architecture student in South Africa, I noticed that the most unhealthy materials (e.g., asbestos) were used for housing the Black population (government housing provided in the segregated townships). My self-chosen projects in my fifth year of study were schools, as I could see that education was a key component of change in South Africa, and my final project, my thesis project, was the design of a self-help preschool in a Black township near Cape Town.

I was very naïve at the time! The project was never built; by the time I left the country in July 1977, weeks after I had graduated with a Bachelor of Architecture degree from the University of Cape Town. However, I did work closely with the community to select the site and to understand their needs for the school. During one of my site visits, I was “entertained” by the Black security police, wanting to know what I was doing in a Black township, and also wanting to meet my Black friends with “similar ideas.” They never got to meet anyone.

In the meantime, Anthony’s father, Felix, ran Felicity Stores to make an income, but his passion was the work he did as a handwriting expert. Anthony remembers that

he maintained he was self-taught. He was an expert witness in court cases, where he [even] testified about the author of forged documents. He also prided himself on being able to describe people’s character from their hand writing.

When Felix died, on November 5, 1982, he was 76 years old. His widow, Miriam, returned to Birmingham, England, where she passed away on April 3, 2004. She was 88.

In relentless adaptation, Alfred, Bertha, Helene, Siegbert and Felix, all five Passau Bernheims, had managed not only to survive the Shoah, but to enable all their respective descendants to gain new footing in fields of their own choosing.

Going “Green” in San Francisco

In 1969, Cape Town had a total population of 750,000. Approximately 25,000 were Jews. After Johannesburg, it was the second largest Jewish center in South Africa. In addition to 12 orthodox congregations, Cape Town had two reform congregations. From 1970 until 1992, approximately 10,000 Israelis immigrated. During the same period, however, some 39,000 Jews left South Africa.[12] Among those was Felix Bernheim’s only son, Anthony.

He recalled on March 14, 2021:

On arrival in the San Francisco Bay Area, I set about getting work in various architects’ offices, getting licensed in California as an architect. During this formative period, I thought that I should go back to university and get a Master of Architecture degree so that I could learn what other U.S. architects knew and become more competitive at finding work. While working part time for an architectural firm designing affordable housing projects, I was also attending the University of California, Berkeley, School of Architecture. My employer, who was also the chair of the School of Architecture at the time, suggested that I take one class in Building Ecology. For that class I wrote a paper on why vinyl asbestos tile flooring was a human health hazard. Through some additional efforts that I made, that product was withdrawn from the market six months later.

On June 2, 1981, Bernheim became a U.S.-citizen. Three years later, he received his Master of Architecture degree from the University of Berkeley, California. In 1985, when Bernheim was 32, his son, Micah Bernheim Burger, was born.

For over 30 years, Anthony has pioneered integrated, sustainable building practices. His expertise promoted not only a significantly healthier indoor air quality, but the FAIA, LEED Fellow made a name for himself as an architect addressing a wide range of building types and master plans.[13] Looking back, he summarized on March 14, 2021:

During my many years working at SMWM, opportunities arose for me to help projects become healthier and more sustainable. In many cases, the client asked some questions or SMWM thought I might know something. Each opportunity presented another step in my professional and personal development of sustainability practice.

However, the key to my development was writing and presenting peer reviewed papers for international and local research and scientific publications on my work I. I also took on speaking at architectural and building conferences. The big obstacle I had to overcome was my shyness. I had to learn to speak in public. By the 1990s, I had met the founder of the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), and helped him develop the first sustainability manual for green buildings. Then I helped to form the Northern California Chapter of the USGBC, and have served on the local USGBC Board and committees, and for five years on the national USGBC Board of Directors.

The work I started to do in the late 1970s involves healthier built environments for all building types. It includes reducing or eliminating the sources of pollutants; designing the heating, ventilating, and air conditioning systems; testing the systems and training the building engineers prior to occupancy; and setting the buildings up for environmentally preferable green cleaning during the life of the building.

Improved health of people and of the planet includes energy and water efficiency (with related carbon emission reductions). Long-term sustainability is based on providing triple bottom line solutions.[14]

In South Africa I learned about social justice. In the U.S. I learned about environmental responsibility. I have combined both of these principles, along with financial responsibility, in my professional practice as an architect.

Bernheim’s projects have led to healthier environments.

In the 1990s, he was the architect’s project manager and the sustainable building practices leader for the new San Francisco Main Library, one of the first major public projects in the U.S. to have the indoor materials tested for chemical emissions. For the State of California Capitol Area East End Complex office building he collaborated as an architect with other indoor air quality professionals on the development of project specifications, for testing to improve building products for chemical emissions to reduce indoor air chemical concentrations to building occupant health. This work has led to improving building product emissions, and the way third-party certifiers evaluate products, and has provided the basis for the indoor air quality requirements of the new California and national green building codes and standards.[15]

Today, the architect lives in San Francisco, California. He is married to Sara Tung from Southern California, whose parents fled China at the end of the Communist Revolution in 1949.[16] Anthony’s son, Micah, is a design strategist.

Anthony Bernheim is the past chair of the U.S. Green Building Council Northern California Chapter (USGBC-NCC) Board of Directors. He was a member of the USGBC National Board of Directors, Treasurer, Vice-chair of the USGBC Green Buildings and Human Health Working Group, and Co-chair of the USGBC Classroom to Boardroom Diversity Mentoring Initiative.

Currently, Bernheim is the Healthy & Resilient Buildings Program Manager for the San Francisco International Airport. Recently, he wrote “Clean Air: Good Health” and “Ambient Outdoor Air Quality,” two chapters for [the] Wiley Publications books “Sustainable Healthcare Architecture” and “Sustainable and Resilient Communities” respectively.

“In recognition of a lifetime of service, commitment, and advocacy for the principles of sustainable design and preserving the earth’s natural resources,” Bernheim was honored with the AIA California Council’s 2004 Nathaniel A. Owings Award. Five years later, the USGBC Northern California Chapter handed him the David Gottfried Special Achievement Award for being “an individual whose career and contributions to the industry demonstrate exceptional passion, leadership, and commitment to green building”. In 2012, Bernheim received the “Breathe California Clean Air Award” for his work on “green” buildings, and in 2020 the “Airports Going Green Award”, recognizing “Leadership in Development Practices for High Performance Buildings, Representing Outstanding Achievement in Pursuit of Sustainability within the Aviation Industry.“[17]

In spite of such laurels, the trailblazing architect remained as humble as determined. On March 14, 2021, he wrote:

In many ways, I was very lucky professionally. Opportunities presented themselves, and I was able to build on them. Working on large public projects, being published, speaking at conferences, writing chapters for books, developing relationships through my continuing contribution to the US Green Building Council and support from their founders – all contributed to the work that I am doing now at the San Francisco International Airport. In a way, I was preparing for this opportunity.

While my work on human health in the built environment was just part of my work previously, it became front and center last year as the COVID-19 pandemic started, and I was asked to help develop ways to make the indoor environment at the Airport healthier and safer. So, while working on health in the built environment at this airport, my goal is to help improve its environment campus wide, to become more sustainable and resilient for the long-term, and thereby to improve health for passengers and employees as well as to improve global health.

In Memoriam

By the end of 1939, more than 117,000 Jews had left Austria, and more than 300,000 fled Germany. Most of them were young, vocationally trained or college-educated. Many, if not most of those who fled to neighboring countries, were captured, and many of the 100,000 who initially found refuge, were killed after May 1940, when Germans invaded.[18]

Mathilde Bernheim, Alfred’s mother, died on May 21, 1941. She is buried in the Rusthof cemetery[19] of Leusden near Amersfoort.

When Albert and Rosa Loose, the older sister of Alfred Bernheim, received a summons of Joodse Raad,[20] Hedwig Loose and their oldest grandson, Peter, accompanied the elderly couple to the train station.[21] They were sent to Westerbork.[22] On May 4, 1943, both arrived at SS-Sonderkommando Sobibor, an extermination camp in the Lublin province of Poland, where they were officially declared dead three days later.[23]

Julie Loose, the widow of Albert’s brother, Max, was imprisoned in the Munich barracks camp at Knorrstraße 148 from January 2, 1942, and deported to Theresienstadt on July 29, where she perished on April 7, 1944.[24]

Gerda Moos, née Stern, the younger daughter of Martha Bernheim, and aunt of Margot Rudnick, and her husband, Kurt, emigrated to the Netherlands on February 6, 1939. They lived in the Hillegersberg suburb. Most likely to rescue their very young daughter, Yvonic, Max traveled to Paris with her.[25] Gerda was declared dead in Auschwitz, Poland, on September 21, 1942.[26] Her husband, Kurt, was deported from Drancy,[27] France, on September 18, 1942 and declared dead in Auschwitz, on December 31, 1941.

Tim Rudnick added on March 8, 2021:

My brother Nicholas has some pictures of my mom and her parents. Elsie died 2006 in Bulawayo, at the age of 98, and Herbert Kirstein died there at the age of 65. My Oma, Martha Stern, was a lovely woman, she was a milner, and also did some beautiful embroidery work, some of which still exists, I think. She passed away in Bulawayo in the early 70s, approximately 95 years old. Her husband, Max Stern, whom I never met, was quite instrumental in keeping in contact with Elsie’s sister [and her husband]. They were captured in France, en route to Switzerland from the Netherlands. Both passed away in the camp from disease.

My sister said Yvonic fell ill, so her parents had to stop their journey, and take her for medical treatment. While there, her parents either had to flee or were captured. Yvonic, was taken [in] by a French farming family, and brought up Catholic. She bears a striking resemblance to Elsie, and now lives in Dijon, where she is married to François Duriez.[[28]]

Max was in touch with someone in Buenos Aires, who had a network to trace Jews to find out their fate. He also wrote to Albert Einstein, a distant relative, for the US government to assist in the evacuation of Jews – I think from the Netherlands. The reply was that they felt the support was more urgent in other areas.

Anthony Bernheim, Charlotte Fassin, Uri and Amos Barneah at the location of their grandparents’ former department store

In 2008, various members of the extended Bernheim family traveled to Germany from England, France, Israel, the Netherlands and the Unites States, to get better acquainted with one another, and to learn about the past of their mutual ancestors. After visiting Bad Buchau, some accompanied all four living Bernheim cousins to Passau, where Georg Höltl welcomed them at two of his hotels as Guests of Honor. The city administration treated them to a luncheon in a traditional restaurant, where in all likelihood, Alfred and Bertha Bernheim used to dine with friends and family. During a walk through the pedestrian zone, they realized that the prison, where Felix was held in 1933, was on the same street where Hitler and Himmler had once lived. And just around the corner, in front of the former Merkur department store, reporters briefly interviewed them.

In 2012, Anthony obtained a German passport for himself and his son.

On March 14, 2021, he wrote:

My parents did not discuss their lives prior to or during World War II, or even how they met (although we have since found out some information from my cousins). Discussing the Holocaust was not done in the 1960s through 1980s in South Africa. It became more acceptable in the late 1980s in the US. So thanks to you – by reading your books, spending some time with you in Baltimore, and participating in the trip that you arranged for my family in Passau in 2008 – I was able to put my parents’ lives into context. I am now better able to understand and appreciate my parents and what they did for me. The gifts they gave me included a safe home, an appreciation of right and wrong, and a sense of social justice. So while I value their efforts, I thank you for what you have done to help me appreciate my parents.

Notes

[1] On November 27, 1956 the village mayor testified that Alfred and Bertha Bernheim, Helene’s parents, came with them.

[2] Shoshana Barneah, Siegbert’s daughter-in-law, learned about that time from Helene in 1972. She recalled on March 5, 2021: “Helene lived below her parents, and she mentioned that she used to knock on the ceiling with a broom, when her parents were speaking German loudly. It was a reminder to stop. She also told me that their neighbors were very kind towards them, and used to warn them, every time when Germans arrived.”

[3] Marie Clauzolle testimony from March 25, 1958. Courtesy of Margaux Fassin, Helene’s great-granddaughter.

[4] In December 1946, Alfred and Bertha joined heir son Siegbert Bernheim in Palestine. For details about that period see: Rosmus, Anna: Exodus – Im Schatten der Gnade. Aspekte zur Geschichte der Juden im Raum Passau. Dorfmeister, Tittling 1988, pp. 69-71

[5] https://www.jta.org/1933/11/05/archive/cape-town-picks-a-jew-for-mayor

[6] Kenkmann, Alfons, Rusinek, Bernd-A.: Verfolgung und Verwaltung – Die Wirtschaftliche Ausplünderung der Juden und die Westfälischen Finanzbehörden. Münster 1999, p. 19

[7] For details see: Mendelsohn, Richard and Shane, Milton: The Jews in South Africa, an Illustrated History, Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg & Cape Town, 2008, pp. 110 and 111.

[8] For details see: Sichel, Frieda H.: From Refugee to Citizen: A sociological study of the immigrants from Hitler-Europe who settled in South Africa, A.A. Balkema, Cape Town, 1966

[9] Dmitri Abrahams, archivist at the South African Holocaust and Genocide Foundation (SAHGF), “Finding traces of German Jewish refugees in South African archives” in the Cape Jewish Chronicle from October 4, 2019;

[10] The Department of the Interior published Certificate of Naturalization number 22370 in the Government Gazette from January 28, 1944.

[11] Janis Rochelle Burger from South Euclid, Ohio, had a Bachelor of Arts degree in psychology from Boston University and a Master of Public Health degree from the University of California, in Berkeley.

[12] https://www.anumuseum.org.il/jewish-community-cape-town/ Retrieved on March 3, 2021

[13] He “was the Sustainability Manager for The Allen Group, and the Director of Sustainability, AECOM Architecture, where he collaborated on the development of the AECOM ecoSystem, a dashboard toolkit used to guide integrated building practices from project inception through post occupancy of high-performance buildings that are energy-efficient, provide comfortable, safe, and healthy environments, utilize resource-efficient products, have reduced environmental footprints, and strive to be ‘living’ and ‘regenerative’ buildings.” See: https://www.linkedin.com/in/anthony-bernheim-a5bb627/

[14] The triple bottom line concept, developed by the UN Brundtland Commission, formerly known as the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), states that to solve for sustainability we need to solve for environment responsibility, social equity, and financial responsibility (Planet, people, profit).

[15] See: https://www.linkedin.com/in/anthony-bernheim-a5bb627/

[16] Sara holds an MA in History and an MBA from the Graduate School of Business, at Stanford University. “In addition to being refugees,” Sara wrote on March 14, 2021, “both sets of parents had also lost family members left behind and had emigrated to other countries (in my parents’ case, the U.S.). We also have shared experiences living under the authoritarian governments of apartheid South Africa and China.”

[17] https://sfoconnect.com/about/news/sfo-manager-wins-national-sustainability-award

[18] “Refugees” in: Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Washington, DC.

[19] Amersfoort General Cemetery, as it is occasionally called, is a civilian and military cemetery for victims of WWI and WWII. Included are 238 soldiers killed in action from the British Commonwealth, Belgium, France, and Poland, military victims from Italy, Hungary, Romania, Portugal, Yugoslavia, Greece, and Czechoslovakia, as well as 865 soldiers from the Soviet Union.

[20] The Joodse Raad, a Jewish council, had to mediate the occupation government’s orders to the Dutch Jews and, beginning in July 1942, to help with the selection of Jewish deportees from the Netherlands to work camps. In September 1943, most staff of the Joodse Raad was deported as well.

[21] On July 4, 2013, Anjes Brooijmans wrote that Peter’s widow, Marianne, told her how often her traumatized husband talked about that event, even during the final days of his own life.

[22] Established by the Dutch government in October 1939 to intern Jewish refugees who had entered the Netherlands illegally, the camp continued to function after the German invasion in 1940. From July 1942 until September 3, 1944, 97,776 inmates were deported from Westerbork.

[23] This information is based on Anfragekarte (inquiry card), ITS Object id: 27778712, which directs researchers to Tracing and Documentation File number 625 299 at the International Tracing Service archives in Bad Arolsen, Germany. The dates are also reflected on a list of victims from the Netherlands, “In Memoriam – Nederlandse Oorlogsslachtoffers”, Nederlandse Oorlogsgravenstichting (Dutch War Victims Authority), `s-Gravenhage.

[24] See: Gedenkbuch – Opfer der Verfolgung der Juden unter der nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft in Deutschland 1933-1945. For May 18, 1945, Dr. Franz Loose and his wife in New York City and Walter Frank with his wife, Fanny, née Loose, in Newark, NJ, placed an obituary for their mother in the Aufbau.

[25] According to Anjes Brooijmans, Yvonic was born in Rotterdam on May 22, 1939, and sent to a Jewish orphanage in Paris, France. During an attempt to escape to Switzerland, a nurse took Yvonic out of the train, and passed her on to the Catholic Pointier family in Ennemain, within the Somme department of northern France.

[26] The information is based on a list of Jews from Hillegersberg and Schiebroek who perished during the Holocaust. According to Item 1066775, a “Page of Testimony” in the “Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names” of Yad Vashem, Carla Weiss in Tivon erroneously declared on April 28, 1999 that her cousin, Gerda, died in France, “Shot trying to escape to Switzerland.” Another error on that page lists Gerda as born in 1906.

[27] Located in a Paris suburb, the Drancy internment camp confined Jews. Between June 22, 1942 and July 31, 1944, 64 trains deported 64,759 French, Polish, and German Jews to extermination camps. See: http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/this_month/resources/drancy.asp.

[28] Yvonic and her husband adopted two children. Anne was born in 1969, Remi in 1971. Both were nearly two years old.

Comments Off on From Time to Time: Turning a curse into blessings. The Bernheims after Passau in Cape Town and San Francisco (Part 2 of 2)