Nov 2011

Reinhard Zachau

Death Images in The Baader Meinhof Complex

Abstract

The paper explores the different aesthetic strategies The Baader Meinhof Complex uses to approach the RAF trauma. By incorporating several of Gerhard Richter’s paintings for interpreting original press photos, the movie creates a unique style based on modern art theory, which establishes the film as a central player in the RAF mourning process.

I. Introduction

In his review of the 2008 movie Der Baader Meinhof Complex Ulrich Kriest writes that by focusing on style and images rather than on content and substance the movie capitalizes on the fashionable image the RAF has gained with the current post-Wall generation.[1] Since film is essentially an image-oriented medium, Kriest questions whether it is capable of capturing the core of the RAF, which was known for its brief violent acts, but also its lengthy theoretical manifestos. In this contrast Kriest captures the ongoing debate about the artistic representation of RAF terrorism. In looking over the large body of films about the RAF, it becomes obvious that the focus of the debate has indeed shifted away from the political discourse of the RAF and the original flood of words, whether by the RAF or their many interpreters, has been replaced by an extraordinary number of images. By ignoring a discussion of the political roots of the RAF Thomas Elsaesser claims that we avoid the discussion about the role of capitalism in Western societies.[2]

The Baader Meinhof Complex is the last example in a lengthy series of feature films and documentaries attempting to address the RAF history by straddling the interests of two generations, the first post-WWII generation and the generation Golf/Berlin. In its ambitiously comprehensive goal of appealing to both post-WWII generations the Baader Meinhof Complex movie is the first in attempting to capture the entire ten years of RAF activity from 1967-77. Aspects explored in earlier films were the relationship between the Ensslin sisters (Marianne and Juliane), Andreas Baader (Baader), RAF members hiding in the GDR (The Legend of Rita), the Herrhausen assassination (Black Box BRD) and most often the events surrounding October 18, 1977, the kidnapping of Martin Schleyer and the hijacking of the Landshut plane (Mogadischu, Deutschland im Herbst, Todesspiel).

Thus the stakes for The Baader Meinhof Complex were high from the beginning and its ambitious attempt to authoritatively interpret the RAF history will ultimately influence and define our interpretation of the events.[3] The almost forty-year long fascination with the RAF myth has shaped both post-war German generations. Inge Stephan places the obsession with the RAF in a line with two other traumatic experiences in German history, the holocaust and German unification. To highlight its significance Stephan dedicated an entire volume to the RAF in her three-book series on visual representation of traumatic periods in recent German history, NachBilder.[4] Elsaesser also emphasized the power of movies as particularly suited to dealing with tragic events as they can interpret subliminal and traumatic elements since the moving image can recall memory and traumatic experiences.[5] As Svea Bräunert wrote, basing the mourning process on movies works well within Germany’s consensus-driven society with its tendency to interpret West German terrorism films as part of the foundational trauma on which to build the Berlin Republic.[6]

The unresolved traumatic core of the RAF-debate resurfaces whenever a major movie or public event, such as the 2005 “KunstWerke” exhibit,[7] attempts to define to what extent the RAF constituted a threat to the foundation of the Federal Republic. What became apparent from these debates was that between 1967 and 1977 nobody in West Germany was left untouched by the RAF activities. The activities of the RAF need to be seen as part of a larger political shift, of the power change from the war generation to the next generation, in Germany referred to as the “Sixty-Eight” generation. Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s staged interview with his mother in the movie Germany in Autumn (1978) is still one of the most chilling examples of this debate, when she longs for a “benevolent dictator” in light of the West German inability to deal with the RAF-crisis.[8] This polarization between the older generation raised during Nazi totalitarianism and the first post-WWII generation brought up in a democratic state is the source of this conflict. Surveys reveal that a significant number of citizens were “sympathizers”, to recall the popular term used at that time.[9] Time has erased the memory of why the Baader Meinhof Group was ever popular; in fact it has changed our memory to the point that the current generation no longer knows why the RAF ever appealed to intelligent and sensitive people. By asking why these “preposterous and repulsive figures” [10] who announced the advance of a revolution, were not considered “political porn”, we are able to explore the core of our history with the RAF.

The younger generation’s lack of awareness was the reason for creating the movie. Bernd Eichinger, the producer of The Baader Meinhof Complex, and the film’s director, Uli Edel, both belong to the first post-WWII generation and are contemporaries of Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof, which is also Fassbinder’s generation. Eichinger and Edel met at Munich’s film academy, where they considered themselves “anti-authoritarian”, as were about eighty to ninety percent of students during the late sixties.[11] Eichinger has since become one of Europe’s most prominent filmmakers with movies such as Christiane F, which was also directed by Uli Edel.

Since Eichinger had gained a reputation for falsifying historical facts in Downfall about the Hitler saga, most reviewers were concerned that The Baader Meinhof Complex would take equal liberties with the truth.[13] Eichinger asserted however that he faithfully followed Stefan Aust’s book The Baader Meinhof Complex and changed only minor details.[14]

The issue of veracity in The Baader Meinhof Complex dominated the critical discussion from the beginning. In anticipation of this reaction, Eichinger says he intended his movie primarily for two viewer groups: audiences abroad and the younger generation at home, his own children, not the post-WWII generation that experienced the RAF times themselves.[15] Eichinger repeatedly refers to its internationally positive reception, especially in the United States. However, since German movies in the United States usually appeal to a different audience than they do in Germany, the charge of “dumbing down” the story for an international audience remains valid. Whereas facts about the RAF are mostly unknown to non-German audiences, Germans of the Baader-Meinhof generation will look for a new interpretation of the events in the movie.

II. Aesthetic concepts

The Baader Meinhof Complex incorporates several overlapping aesthetic concepts that include artistic thoughts of the original RAF members themselves. Gudrun Ensslin, Ulrike Meinhof’s rival in leading the RAF, had given each member of the core group a code name based on Hermann Melville’s novel Moby Dick; Ahab stood for Baader and Starbuck for Holger Meins. As we recall, Ahab is the tyrannical captain of the whaling ship “Pequod” who is driven by a monomaniacal desire to kill Moby Dick, the whale that had maimed him on a previous voyage. As a result Ahab ultimately condemns the crew of the Pequod to death by his obsession with Moby Dick. During her imprisonment in Stammheim high security prison Ensslin had read the novel and made the RAF connection to Melville’s tragic tale when she realized their likely fatal end. By using Melville’s novel as a model for the RAF, she became the first to mythologize the group. Ensslin’s recommendation influenced Meinhof whose notes indicate she was also reading Moby Dick in her prison cell.[16] Both recognized the tragic element of the RAF’s monomaniac reach for power, “Größenwahn”, as Helmut Schmidt called it.[17] Thus Theodor Adorno’s belief that antagonisms in society should be replicated in the structure and content of art [18] finds its application in The Baader Meinhof Complex. Ensslin’s linking the RAF to the biblical saga of Ahab and Leviathan elevates the Baader-Meinhof story into a timeless tragic tale of man versus society. Stefan Aust reproduces this tragic structure in his book The Baader-Meinhof Complex by dividing the text into five dramatic parts, “Paths into the underground” (exposition of the story), “Splendor of terror” (the terror develops), “Costume of fatigue” (the tragic turn), “Court Session “ (giving up hope), and “Fall 1977” (the end).

As movies are governed by images, whether authentic or reconstructed, the presentation, recreation and editing of those images, establishes the event in the collective memory. The dramatist Leander Scholz, a member of the second post-WWII generation, is convinced that the RAF texts will not survive but the images that he still remembers will.

Eichinger uses recreated images as a major structuring device, thereby shifting the emphasis away from manifestos. In his highly visual movie most viewers will not grasp the full scope of action at first, but they will relate to the emotional intensity of the events. Heinrich Breloer had been one of the first to show the attack on Hanns-Martin Schleyer in his docudrama Todesspiel (Death Game); however, Breloer’s long shots allowed less immediacy than Edel’s close-ups.[20] Eichinger’s claim that he produced an “objective” movie with high documentary power, “what the film tells is authentic”, cannot be taken at face-value although Eichinger backs his claim up with original TV footage, which was incorporated in some of the reenactment scenes.[21] With its image-based scenes, the film turns the RAF story into an action movie with the emphasis on characters, which “immerse” the viewer in intense close-up scenes.[22] These scenes, accompanied by a powerful musical score, generate a very personal movie with its dizzying litany of dates and locations, and “the ever-present blast of gunpowder.”[23] The result is a new heritage film, as Lutz Koepnick calls it, which does not challenge history as auteur films of the Sixties did, but uses Hollywood techniques in order to represent a “historic consensus”.[24]

However, this general statement needs to be modified since there are several instances where the film achieves an uneasy intensity normally not found in Hollywood movies. This intense proximity to the protagonists has been called political pornography[25] and achieves a degree of sympathy for the protagonists. Frank Schirrmacher described Eichinger’s reenactment method as a cinematic cloning of an entire world, where the recreated scene is almost indistinguishable from the original.[26] This is especially true for Andreas Baader, who as the leader of the group had achieved the highest degree of iconization. Thorwald Proll described Baader as a movie buff with aspirations of looking fashionable since he himself had written movie scripts inspired by French nouvelle vague films [27] such as Breathless.

With his interest in avantgarde cinema, Baader lived in his own artificial world of movie characters such as James Dean, Jean Paul Belmondo and Marlon Brando.[28] While Ensslin saw the RAF more along mythological lines, perhaps due to her upbringing in a protestant minister’s family, Baader’s perspective was more radical, innovative and reminiscent of the West German radical leftist Sponti-scene of the nineteen-seventies. It is obvious that Jean-Paul Belmondo’s character Michel in Breathless along with Clyde Barrow in Bonnie and Clyde became a model for Baader and later also for Ensslin during their time in Paris. The Parisian underground lifestyle shown in Breathless also began to appeal to Ensslin, which she emulated along with Baader.[29] They appear to be kindred spirits with their preference for fast cars and avant-garde fashion. One particular scene in the 1966 movie The Battle of Algiers became the model for the Berlin bank raids in which three banks were robbed simultaneously.

Baader’s and Ensslin’s reenactment of cinematic fantasies appeals to the current “Generation Berlin” that has been brought up on movie fantasies and has trouble separating art and life.[30] Several other scenes resemble film scenes as well, such as the baby carriage scene, which stopped Schleyer’s car and looks like a scene from an Eisenstein movie.[31] It seems indeed that the RAF considered themselves artists who wanted to turn West Germany into a stage for a didactic play in Brecht’s tradition and saw themselves as actors in a play.[32] Their existence depended largely on spectacular actions such as bomb explosions, which stopped life like photoflashes to record the moment for their and our collective memory.[33] The current generation Berlin mythologizes the RAF as seventies pop culture icons, which West Germany never had.[34] At this point the heritage movie turns into a nostalgic movie glorifying the seventies.

III. Mediation

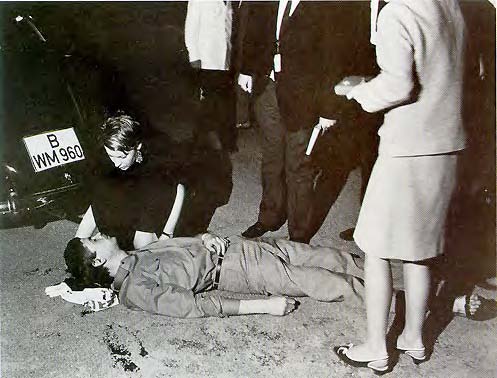

No previous RAF movie attempted this degree of recreating its history with a calculated emotional response. In order to achieve its goal The Baader Meinhof Complex employs several strategies. It is shot in a nouvelle vague look which cameraman Rainer Klausmann created by copying authentic press photos.[35] With refined film technology, reenactments are a common method to recreate original black and white photographs.[36] One of the best examples of an iconic image the movie uses is Jürgen Henschel’s June 2, 1967 photograph of Benno Ohnesorg’s death, which still represents the most dramatic moment of the first fatal shooting victim of a police officer. As witness of the event, Henschel’s photo stands out among others with its use of flash photography highlighting the pietá effect of the well-composed shot. This original photograph shows the climax in the chain of events when the woman assisting Benno Ohnesorg, Friederike Dollinger, turns to the photographer with an expression of desperation. In comparing the Larssen photo with Henschel’s the attraction of the latter becomes apparent. In Henschel’s photo the flash captures the plea for help in the woman’s face while cradling Ohnesorg’s head, whereas Larrsen missed the “pregnant” moment because Dollinger had turned her head back to the dying Ohnesorg.

In recapturing and reenacting this scene, Edel does not use the bright flash of Henschel’s original but instead immerses the scene in uniquely obscure light, which removes the unevenness of the flash. Edel explains:

[37]The French call it cinema vérité. When we put the lights on a set, we would only enhance the natural or available light rather than adding dramatic “movie light.” And we avoided dolly shots or contrived camera angles. Most of the film was shot with a hand-held camera, giving the actors as much freedom as possible. They didn’t have to follow the camera because the camera followed them.

Frank Schirrmacher called the lighting effect “heartbreaking” since it creates a heightened sensibility in the viewer. The light makes the movie look more like a science fiction movie, “as if the figures were shown through an aquarium or a clear water surface,“[38] a cool and modern effect, which “hurts our eyes.” The effect is mesmerizing. With his technique Klausmann’s lighting transcends the intended authenticity and creates a film that seems more perfect than a documentary, as the complete shot below shows.

As the scene sequence demonstrates, Klausmann framed his shot with the original photographer inserted into the scene, thereby adding another layer for the current viewer that did not exist in the original. The effect is that we are constantly reminded of watching a mediated event.[39] The cool and distancing light is also reflected in the actress’s expression that no longer shows the shock of the original photograph.

Edel uses TV sets and doors or window frames to show the mediated images of Ulrike Meinhof. An important example is Meinhof’s 1972 jump out of the window of Berlin’s Institute for Social Studies where she assisted Andreas Baader in shooting his way to freedom. The frame serves as an important internal device in the movie to structure Meinhof’s biography since she left her regular life behind with this jump to begin her career as an underground terrorist.

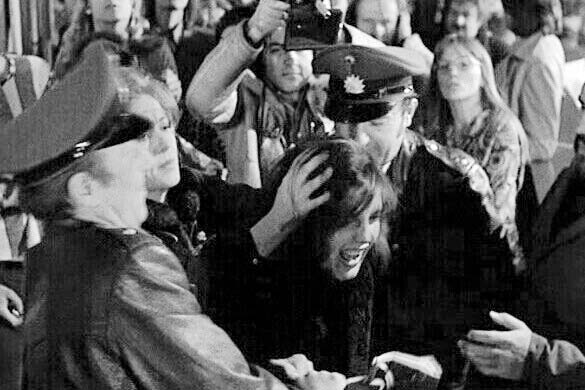

The picture showing Ulrike Meinhof’s arrest in 1972 has a similar effect. As in the Ohnesorg photo, Meinhof’s original arrest photo seems raw and unrefined with the flash highlighting her face, along with the jagged and crude movements of the arresting policemen. The aggression in the authentic photo originates clearly in the police, not with Meinhof because the picture shows the presentation of her for the media.

This image of Meinhof’s arrest influenced the writer Heinrich Böll’s 1974 novel and the 1975 movie version The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum, in which Volker Schlöndorff presents a similar scene in the arrest of the fictional Katharina Blum character. Schlöndorff’s movie shows a fictionalized story about the very first phase of the RAF, which is based on Heinrich Böll’s relationship with Ulrike Meinhof who he had defended in a Spiegel article. Although no terrorist himself Böll was considered a “fellow traveler”. Like his fictitious character Katharina Blum, he was hounded by the press. While Böll protested the search of his house and arrest of his guests, Katharina Blum knew no other way to defend her honor than by shooting the journalist responsible for fabricating stories about her connection with terrorists. Böll’s story demonstrates how during those days of overreacting police and press in West German any ordinary person could be regarded as a terrorist.

Edel copies Schlöndorff’s scene in framing his action for his Ulrike Meinhof character through the camera lens. As in the Ohnesorg sequence, Edel again portrays Meinhof’s arrest scene in his signature uniform light. A single policeman uses his hand to touch Meinhof’s shoulder lightly, to support her sagging torso rather than to present her to the camera as in the original photo. Edel centers on her expression, which seems subdued; he interprets her arrest as a mental and physical breakdown. Unlike in the original photo and Schlöndorff’s movie, Edel’s Meinhof does not show any reaction, but only exhaustion. Her tears at her arrest do not show her as weak but as human.[40] As her aggressive emotions have disappeared we recognize the filmmakers’ attempt to change the revolutionary posture of Meinhof into a slumping and sad woman who has given up.

A similar pattern of inter-medial interpretation can be seen in the arrest scene of Andreas Baader, Holger Meins and Jan Carl Raspe, which is framed by a picture of a girl taking a photo of the event. We witness a sequence of shots, first the advance of the police, then Raspe’s arrest, which is followed by Baader’s and Meins’s retreat into one of the garages, followed by the shooting of Baader, and finally the arrest of Meins and Baader. By assuming the child’s point of view, the camera copies the location of the original police photo and makes the girl the key witness for this scene. As a ten-year old, this child is the witness for all of those viewers who were children during the nineteen-seventies, Eichinger’s intended target audience.

In order to extract Meins and Baader from the garage where they had barricaded themselves, the police used teargas, which blurred the arrest scene. In the Meinhof arrest scene Klausmann’s camera had focused on her face and invited identification and sympathy with the victim, which was reinforced by her submissive expression, with no hint of the aggression shown in the authentic photograph. However, in Baader’s and Meins’ arrest scene, the camera does not close in, but pulls back to a long shot which obscures Baader’s shooting in a foggy teargas scene. By focusing on the girl as its point of view, the movie does not provide the identification that it did with the medium shot of Ulrike Meinhof’s arrest.

IV. Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter used the same shot in his painting “Arrest 2 (Festnahme 2)”, which is part of his cycle “October 18 1977” where, in typical Richter fashion, the scene shows a copy of the original press photo.[41] “Festnahme 1 and 2” are part of a fifteen-part painting cycle, all executed in Richter’s grey and black style and arranged like a mini-film with subsequent shots. They are difficult and irritating to explore since the viewer cannot distinguish many details in the fuzzy brush-over paintings.[42]

Like Böll Richter belongs to the older war generation who survived the Nazis, but unlike Böll, the East German Richter knew firsthand what Communism meant. By focusing on the death of the terrorists, Richter wants to show the sadness he experienced when he was looking at these images.[43] This sadness reflects the sadness he experienced as the communist system was collapsing, which he saw as the end of an era but also as the end to the idea that humans can change society by ideological concepts. As an expression of his own mindset in the 1980s, Richter’s cycle of paintings is a powerful illustration of conceptual art. Although many of Richter’s original photos were based on color photographs, all fifteen are washed in muted grays to express an overall notion of despair.[44] Although Uli Edel and Rainer Klausmann were only interested in representing the original setup of Baader’s arrest scene, the resulting long shot shows an amazingly similar effect to Richter’s. The blurring in Richter’s painting has been replaced by the tear gas.

Edel’s attempt to distance the viewer from the action is further reinforced in one of the final scenes in the movie, showing Gudrun Ensslin’s suicide in her Stammheim prison cell. This scene is strikingly similar to Richter’s almost identical painting entitled “Hanged” (“Erhängte”) of the same scene. Richter’s rendition is closer to the original press photo of the body hanging in front of the window, with a black curtain pulled to left side, disguising the body. Richter frames the figure through an exaggeration of the blanket, which is now a black curtain to the left of the image, and the bright white of the wall that runs along the right side of the frame.[45] When the image originally appeared in the magazine Stern, Ensslin’s body was depicted in a full-frontal shot in which all but the window frame behind her and the ground beneath her feet was cropped. A tape measure ran the length of her body in a gesture of scientific rationalization. The resulting photograph is a medium shot of Ensslin hanging by her neck from the bars of her jail cell. The painting’s blurred effect is so pronounced that only the barest photographic fact remains visible; yet one detail of “Hanged” continues to haunt: On the wall facing Ensslin’s face but also facing ours, is a frame which could be either a mirror, a window, a picture under glass, or even an oil painting.[46]

Edel shows the scene in a carefully balanced framed shot, including the attending physician on the left and the prison guard in the right foreground. As in Baader’s arrest scene, Richter’s obscured image strains our eyes and forces the viewer to search for clues in order to comprehend the image. Edel achieves a similar effect through balance and subdued lighting. We recall Schirrmacher’s description of the movie lighting as science-fiction-like and heartbreaking,[47] which seems fitting for a movie that focuses increasingly on death scenes, and which underscores the overall tragic narrative.

V. Recontextualizing the images

In some of its most sensitive scenes The Baader Meinhof Complex movie shows an uncanny interpretation of artistic renditions. As Roland Barthes wrote, Gerhard Richter’s artistic concept proves that death is the essential form of photography.[48] The repainting of the police-commissioned photographs of the RAF in the October 18, 1977 cycle revives the repressed trauma in the minds of their viewers, since so many of the RAF photographs were, according to Storr, all but inaccessible to the public. Therefore these recovered images remain a potential agent in the process of witnessing unresolved traumatic historical events. Richter writes that instead of provoking horror, the paintings cause grief: [49]

[T]he public posture of these people: nothing private, but the overriding, ideological motivation. And then the tremendous strength, the terrifying power that an idea has, which goes as far as death. That is the most impressive thing, to me, and the most inexplicable thing; that we produce ideas, which are almost always not only utterly wrong and nonsensical but above all dangerous. (Gerhard Richter: The Daily Practice of Painting)[50] For Richter the terrorists’ death marked the emancipation from “the illusion that unacceptable circumstances of life can be changed by this conventional expedient of violent struggle,” from “ideology,” and from the cycle of “deadly reality, inhuman reality; our rebellion; impotence; failure; death.” [51] As Richter’s paintings pull the viewer into the scene, so do the movie shots; in fact, the movie ends with an interpretation of Martin Schleyer’s death scene. His body is dropped on a pillow of dry fall leaves with subdued amber light resembling the color of Meinhof’s family scenes at the beginning of the movie.

By using artistic interpretations of the RAF images, the movie incorporates various stages of the mourning process. It turns into an epitaph for the RAF dead, both culprits and victims as in Hans-Peter Feldmann’s photo cycle “The Dead” (“Die Toten”, 1998) in the exhibition held in 2005 at the Berlin Kunst-Werke entitled “Regarding Terror”. It becomes apparent that the generational shift from Böll’s war generation to the postwar “Sixty-Eight” generation of Baader and Meinhof and to the current post-Sixty-Eight generation of Eichinger’s children has been translated into an aesthetic concept in The Baader Meinhof Complex. While Böll felt an affinity with the Sixty-Eighters, Richter’s concept finds greater resonance with the generation “Berlin” that has been dealing with WWII on a different level by working through its traumatic consequences. The overwhelmingly positive reactions to Richter’s and Feldmann’s exhibits in Germany affirm that The Baader Meinhof Complex found indeed an appropriate way to present the RAF.

Notes

1 Kriest, Ulrich: Der Baader Meinhof Komplex. Film-Dienst, 12/19/08. http://www.filmzentrale.com/rezis2/baadermeinhofkomplexuk.htm

2 Elsaesser, Thomas. Terror und Trauma. Berlin: Kadmos Kulturverlag, 2007. Print.

3 In German the term “Deutungshoheit” is used which defined the meaning and connotations of a political term.

4 Stephan, Inge and Alexandra Tacke (Hrsg.). NachBilder der RAF. Köln, Weimar, Wien: Böhlau, 2008.Print

5 Elsaesser, Thomas. Terror und Trauma Berlin: Kadmos Kulturverlag, 2007. Print.

6 Braeunert, Svea. “Replaying Terror: Prosthetic Memories of the RAF and the German Heritage Film.” Manuscript, 2009.

7 „Zur Vorstellung des Terrors“ Berliner Kunst-Werke 2005: http://www.artnet.de/magazine/zur-vorstellung-des-terrors-in-den-berliner-kunstwerken/

8 Fassbinder, Rainer Werner et al. Germany in Autumn (Deutschland im Herbst, 1978) Film.

9 Conrad, Vera (with Ulrich Steller und Regine Wenger). Filmheft Der Baader Meinhof Komplex. Education GmbH. Herrsching, 2009. Print.

10 Knörer, Ekkehard: „Terror.“ 24.09.2008. http://www.perlentaucher.de/artikel/4953.html.

11 Filmheft. Edel seems to have played a bigger role in Munich’s anti¬establishment groups than Eichinger. In Munich both were at a considerable disadvantage in their political development in comparison to the action in West Berlin with its precarious political status as a US outpost, which may explain their more moderate political perspective.

12 Edel is chiefly known in the United States for the movie Body of Evidence, which showcased Madonna.

13 Hake, Sabine. “Historisierung der NS-Vergangenheit. Der Untergang”. NachBilder des Holocaust. Böhlau: Cologne, 2078, 188-218. Print.

14 Herold’s assistant e.g. was added to give him a dialogue partner.

15 In its attempt to serve many different viewer groups The Baader Meinhof Complex elicited a similar German reaction as the NBC production Holocaust in the nineteen-seventies when critics contended that the holocaust should not be reenacted on TV.

16 Aust, Stefan. Der Baader-Meinhof-Komplex. Hoffmann und Campe Verlag, Hamburg, 2008. Print.

17 Schmidt, Helmut. “Interview.” Todesspiel, dir. by Heinrich Breloer, 1997. Film.

18 Adorno, Theodor W. “Rede über Lyrik und Gesellschaft” Noten zur Literatur, hg. v. Rolf Tiedemann, Frankfurt/M. 1981, 49-68. Print.

19 Tacke, Alexandra. „Bilder von Baader“. Inge Stephan, Alexandra Tacke (eds.). NachBilder der RAF. Köln/Weimar/Wien: Böhlau 2008: 62-87. Print.

20 Kurbjuweit, Dirk. “Bilder der Barbarei.” Der Spiegel, September 8, 2008. Print.

21 Filmheft, op. cit.

22 Filmheft, op. cit.

23 Yue, Genevieve: “World Gone Wrong.” Reverse Shot 25, http://www.reverseshot.com/article/baader_meinhof_complex 24 Koepnick, Lutz. “Reframing the Past: Heritage Cinema and Holocaust in the 1990s.” New German Critique 87 (Fall 2002), 47-82. Print.

25 Kriest, op. cit., Knörer, op. cit.

26 Schirrmacher, Frank. “Der Baader Meinhof Komplex.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 14. September 2008. Print.

27 Filmheft, op. cit.

28 Tacke, Alexandra (with Inge Stephan). „Einleitung“. Inge Stephan, Alexandra Tacke (eds.). NachBilder der RAF. Köln/Weimar/Wien: Böhlau 2008, 7-23. Print.

29 World Gone Wrong, op. cit.

30 Berendse, Gerrit-Jan. “Schreiben im Terrordrom. Gewaltkodierung, kulturelle Erinnerung und das Bedingungsverhältnis zwischen Literatur und RAF-Terrorismus.” edition text + kritik 2005. Print.

31 Elsaesser, op. cit., 83.

32 Elsaesser, op. cit., 100

33 Elsaeser, op. cit., 23

34 Elsaesser, op. cit., 25

35 Filmheft, op. cit.

36 Therefore Steven Spielberg’s movie Saving Private Ryan is seen as superior to authentic photographs.

37 Edel interview under http://www.baadermeinhofmovie.comcastcrew/edel_interview.html

38 Schirrmacher, op. cit.

39 Edel copied a number of framed scenes from Breloers Todesspiel.

40 Kothenschulte, Daniel. “Belmondo Baader”. Frankfurter Rundschau, September 17, 2008. Print.

41 Dettweiler, Marco. “Wenn Terroristen-Bilder verwischen”. Der Spiegel, February 20, 2004.http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/gesellschaft/0,1518,286889,00.html

42 Richter chooses his images from a cache of photographs he collects which are then projected on a large screen, where he copies them meticulously onto the canvass. At this enlarged stage they are unbearable in their detail, as Richter states, and subsequently, he obscures them again in his process by brushing over the image again with grey white paint.

43 Storr, Robert. Gerhard Richter: Doubt and Belief in Painting. The Museum of Modern Art, New York 2003. Print

44 World Gone Wrong, op. cit.

45 Guerin, Frances. “The Grey Space Between: Gerhard Richter’s 18. Oktober 1977”, Frances Guerin. The Image and the Witness: Trauma, Memory and Visual Culture. London, New York: Wallflower, 2007

46 Horowitz, Gregg. Art and Mournful Life. Stanford 2001: 165.

47 Schirrmacher, Frank, op. cit.

48 Roland Barthes in Storr, op. cit.

49 Guerin, op. cit.

50 Richter Gerhard. The Daily Practice of Painting: Writings 1960-1993. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995: 194. Print.

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W. “Rede über Lyrik und Gesellschaft,” Theodor Adorno. Noten zur Literatur, Rolf Tiedemann (ed), Frankfurt, 1981: 49-68. Print.

Aust, Stefan. Der Baader-Meinhof-Komplex. Hoffmann und Campe Verlag, Hamburg, 2008. Print.

Der Baader Meinhof Complex. Paramount DVD, 2009

Karin Bauer, edt. Everybody Talks About the Weather . . . We Don’t: The Writings of Ulrike Meinhof. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2008. Print.

Berendse, Gerrit-Jan. “Schreiben im Terrordrom. Gewaltkodierung, kulturelle Erinnerung und das Bedingungsverhältnis zwischen Literatur und RAF-Terrorismus.” edition text + kritik 2005. Print

Black Box BRD, dir. by Andreas Veiel. 2002. Film.

Braeunert, Svea. “Replaying Terror: Prosthetic Memories of the RAF and the German Heritage Film” Manucript, 2009.

Conrad, Vera (with Ulrich Steller und Regine Wenger) Filmheft “Der Baader Meinhof Komplex,” education GmbH. Herrsching, 2009. Print

Der Baader-Meinhof-Komplex. Dir. Uli Edel Paramount Home Entertainment 2009. Film

Dettweiler, Marco: “Wenn Terroristen-Bilder verwischen”. Der Spiegel, February 20, 2004. http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/gesellschaft/0,1518,286889,00.html

Eichinger, Katja. Der Baader Meinhof Komplex. Filmbuch. Das Buch zum Film. Hoffmann und Campe, 2009. Print.

Elsaesser, Thomas. Terror und Trauma. Berlin: Kadmos, 2007. Print

Hake, Sabine: “Historisierung der NS-Vergangenheit. Der Untergang”. NachBilder des Holocaust. Böhlau: Cologne, 2078: 188-218. Print.

Henatsch, Martin. Gerhard Richter: 18, Oktober 1977. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 1998. Print

Kligerman, Eric. “Transgenerational Hauntings: Screening the Holocausts in Gerhard Richter’s ‘October 18, 1977′” Paintings. Gerrit-Jan Berendse and Ingo Cornils (eds.) Baader-Meinhof returns: History and Cultural Memory of German Left-Wing Terrorism. German Monitor 70. Rodopi: Amsterdam, New York, 2008: 41-63. Print

Knörer, Ekkehard: „Terror.“ 24.09.2008. http://www.perlentaucher.de/artikel/4953.html.

Koepnick, Lutz. “Reframing the Past: Heritage Cinema and Holocaust in the 1990s.” New German Critique 87 (Fall 2002). 47-82. Print.

Kothenschulte, Daniel. “Belmondo Baader”. Frankfurter Rundschau September 17, 2008.

Kriest, Ulrich. „Der Baader Meinhof Komplex“. Film-Dienst, 12/19/08. http://www.filmzentrale.com/rezis2/baadermeinhofkomplexuk.htm

Kurbjuweit, Dirk: “Bilder der Barbarei.” Der Spiegel, September 8, 2008. Print.

Nord, Cristina. „Der Spuk geht weiter: Seit es die RAF gibt, gibt es Filme über die RAF. Damals wie heute ist es schwer, sich den Affekten zu entziehen, die mit ihnen einhergehen. Traumata lösen sich ja nicht durch Aufklärung -sie verschwinden, wenn man lange genau drüber redet.“ taz 20. September 2008:19. Print.

Richter Gerhard. The Daily Practice of Painting: Writings 1960-1993. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995. Print.

Schirrmacher, Frank. “Der Baader Meinhof Komplex.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 14. September 2008. Print.

Schmidt, Helmut. “Interview.” Todesspiel, dir. by Heinrich Breloer, 1997. Print.

Schwartz, S: “Gerhard Richter: ‘October 18, 1977’.” New York Review of Books 49, no. 6, April 11 2002: 16-18.

Seeßlen, Georg. „Der ist an allem schuld!“ epd film, December 19 2008.

Stephan, Inge and Alexandra Tacke (Hrsg.). NachBilder der RAF. Köln, Weimar, Wien: Böhlau, 2008. (Literatur -Kultur -Geschlecht. Studien zur Literatur-und Kulturgeschichte. 24). Print.

Storr, Robert. “Gerhard Richter. Malerei”. Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit. 2002. Storr, Robert. Gerhard Richter: Doubt and Belief in Painting. The Museum of Modern Art, New York 2003. Print.

Storr, Robert. “Gerhard Richter ‘October 18, 1977’.” The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2002.

Tacke, Alexandra. „Einleitung“. Inge Stephan, Alexandra Tacke (eds.). NachBilder der RAF. Köln/Weimar/Wien: Böhlau 2008, S. 7-23. (With Inge Stephan) Print.

The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum, dir. Volker Schlöndorff, 1975.

Todesspiel, dir. Heinrich Breloer, 1997.

Trnka, Jamie H. “The Struggle Is Over, the Wounds Are Open”: Cinematic Tropes, History and the RAF in Recent German Film New German Critique. 2007: 1-26. Print.

Zachau, Reinhard, Forty Years of Böll Scholarship. Literary Criticism in Perspective. Camden House: Columbia, South Carolina, 1994.

Leave a Reply