I’m not one for long, verbose titles; I prefer to let my artwork (if a blog post could be considered such) stand on its own. I suppose that’s why The British Museum and The National Gallery appealed to me, because these museums are arranged in such a way that the art and artifacts are privileged over their context and allowed to speak for themselves. Information is available at both museums for those who want to learn more about an individual piece, but signage is simple and audioguides are discreet.

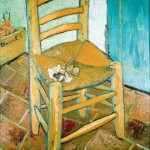

I devoted most of my time spent at The National Gallery to the 18th-20th centuries exhibit, which featured works by Monet, Manet, Picasso, van Gogh and Degas. The piece which affected me most viscerally was Vincert van Gogh’s “Sunflowers,” a painting which I had seen many times on postcards, coasters, prints hanging on water-damaged walls or in the only remains of my mother’s abandoned art degree – in her art books. Seeing this work in person was an incredible experience. Having the opportunity to experience the thoughts, emotions and perceptions of one of the world’s most renown artists though one of the world’s most renown pieces of artwork affected me very deeply. What struck me about works in both museums, but “Sunflowers” in particular, was the work’s enduring relevance diachronically. Though styles and historical contexts are particular to a piece of art and remain fixed, its meaning is mutable. This, I feel, is the true beauty of art.

At The British Museum, I had a similar reaction to seeing and touching part of a column which came from the Parthenon. It is amazing how these artifacts have managed to remain in tact and meaningful for thousands of years. One sign that caught my attention was one which told the story of how Lord Elgin brought pieces of the Parthenon back to England in 1806. The signage, as well as other historians and archaeologists, claims that Elgin essentially saved the artifacts from further destruction and preserved them by bringing them to England. However, now that Greece has the means to afford an appropriate Acropolis Museum, there is much debate regarding the British Museum’s collection of artifacts, uncluding a number of friezes.

Both The National Gallery and The British Museum seem to honor artwork and artifacts over their historical context. Though considering where these pieces came from is crucial in understanding their meaning, perhaps where they are going, such as the friezes and sections of column of the Parthenon, and their relevance to our culture in the present and future is what should be more important.