In an ideal world all vocabulary would be learned contextually, but when trying to learn Latin in a limited amount of time, we usually need flashcards. Guest writer Alex Lee (alexlee@uchicago.edu) describes how to study the DCC Core Latin vocabulary using a nifty piece of software called Mnemosyne, and the electronic flashcards he made for it using the DCC Latin core. Mnemosyne allows for targeted and adaptive use of the cards.

Learning any language involves acquiring a large amount of vocabulary. For this reason, I think it is very useful for Latin and Greek students to put time and effort into systematic vocabulary study.

Learning any language involves acquiring a large amount of vocabulary. For this reason, I think it is very useful for Latin and Greek students to put time and effort into systematic vocabulary study.

One effective way to accomplish this is with flash cards. These days, however, we have the additional option of using special software that removes much of the tedium from the process. More importantly, such software can calculate the best time to present cards for review (using a spaced-repetition algorithm). In this way words can be committed to long-term memory as efficiently as possible.

The value of systematic vocabulary study?

One might reasonably question the benefits of systematic vocabulary study. Strong arguments have been made that vocabulary is better learned in context – that one really acquires new words through actual use. On this view, in which there is a clear distinction between the memorization of word definitions and the actual acquisition of those words, the memorization of vocabulary only helps insofar as it reduces the amount of time spent looking up words. The words thus memorized are not learned or acquired in the real sense, i.e., one is not able to understand and use these words directly and fluidly. Instead, one’s understanding of the word is mediated by the definition that has been memorized.

I’m actually very sympathetic to this view, and I think that any word that has been memorized must be reinforced by actual use, in a meaningful context. Indeed, in the post-beginner stages, new words should be acquired through extensive reading. At the beginner level, however, and when the words in question are core vocabulary words, the systematic study of these words will serve an important boot-strapping purpose. Students will expend less time and energy trying to figure out the meanings and forms of basic words, and they will be less overwhelmed in trying to understand the texts that they encounter. Because the memorized words appear so frequently, it shouldn’t take long before the initial “vocabulary-list understanding” of each word is converted into actual acquisition.

Mnemosyne

The software that I recommend to my students is called Mnemosyne. It is free, it runs on multiple platforms (Windows, Mac OS X, and Linux), and it has a fairly simple interface.

Mnemosyne keeps cards in a virtual deck. You can add new cards individually, or you can import them in bulk from some other source. Cards are organized according to tags. Each card can have multiple tags, and these tags can be hierarchical. For example, all DCC Latin Core Vocabulary cards begin with the tag CoreLatin, and under this grouping they are tagged according to frequency (CoreLatin::1-200, CoreLatin:201-500, and CoreLatin::501-1000) and semantic grouping (e.g. CoreLatin::Measurement).

In the remainder of this post I will describe how to set up and use Mnemosyne to study the DCC Latin Core Vocabulary. (There are similar software packages out there, such as Anki, but I am not as familiar with them.)

This is meant as a sort of quick start guide. For more details and explanation of other features, take a look at the Mnemosyne documentation.

Installation and setup

Go to the download page and fetch the appropriate package for your platform. The installation procedures for Windows and Mac OS X are fairly typical. (Linux users, however, might need to do some additional work, but I assume they will be able to handle that.)

Settings

When you run the software for the first time, select the Configure Mnemosyne… item, which is located under the Settings or Preferences menu. The configuration options are divided among three tabs: General, Card appearance, and Sync server. For options under General, I use the following:

I also recommend looking at the options under Card appearance and setting a larger font.

Import cards

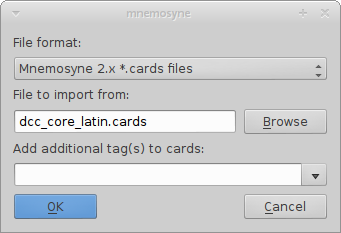

Now you want import the DCC Latin Core Vocabulary cards into your deck. Download the file dcc_core_latin.cards online here. In Mnemosyne, go to File → Import…, choose the file format “Mnemosyne 2.x *.cards files”, and for the file itself click on the Browse button and select the dcc_core_latin.cards file that you downloaded.

Now that you have imported these cards, you can view them using the card browser. Go to Cards → Browse cards…. You should see something like this:

(The filename in the box will look different, depending on where the downloaded file is located on your system.) Leave the additional tags blank, and press the OK button. An additional information window will pop up; you can just click OK again.

Usage

Activating cards

The tags that have been attached to the cards make it possible for you to mark only a subset of cards as “active” at any given time. For example, go to Cards → (De)activate cards…, and in the right-side pane unselect everything except for 1-200. Click OK.

Now the software will only present you with cards with the tag CoreLatin::1-200, which means that you are studying the cards for the words that fall in the top 200 in the frequency rankings. (There are actually more than 200 such cards, but that is because I have split a handful of entries from the list into multiple cards, e.g., longus -a -um and longē.)

In fact, there are twice as many cards as you might expect, because each word can be presented in two ways: for recognition (Latin to English) and for production (English to Latin). The relevant check-boxes are located in the upper left pane, within the item labeled Vocabulary. Most people probably want to start with recognition only, so uncheck the Production box for now.

Learning new cards

At this point the software will prompt you with a Latin entry in the upper box. Try to think of the correct answer and then click the “Show answer” button (you can also press spacebar or enter). The answer will be revealed in the lower box.

Now you need to grade your response (you can click on the button or press the corresponding number key):

- If I had no idea about the answer, I typically select 0.

- If I did not get it right but am getting some vague notion of the answer, I select 1.

- If I think I knew it well enough to remember for a day or two, I select 2 or 3.

- If I knew the word, I select 4.

- If I knew the word immediately and with great ease, I select 5.

Cards that are graded with 0 or 1 will be presented to you again on the same day. If I am in the process of learning a new card, I usually have to grade it as a 1 several times, so that it keeps reappearing within the same session, until I have an initial knowledge of it.

Cards that are graded with 2–5 will be scheduled for subsequent days. The higher the grade, the longer it will be until you see that card again.

Reviewing cards

Cards that you have not yet learned sit in the “Not memorised” pile, while cards that you learned in previous sessions might appear in the “Scheduled” pile (see the status bar at the bottom of the main application window).

If you previously learned a card, the software might decide that you now need to review it. In this case the card will be “scheduled” for today. When you are presented with the card, you must once again grade your response:

- If I forgot the card, I select 1 (sometimes 0 if I totally forgot it).

- If I remembered the card, but just barely or with great difficulty, I select 2 or 3. This means the interval was probably a bit too long.

- If I was able to remember the card correctly, though perhaps with some effort, I select 4. This means the interval was just right.

- If I remembered the card very easily, I select 5. This means the interval was probably too short.

Mnemosyne will keep a record of your progress with each card. The goal is to show you a card just before you are going to forget it again, as this is supposed to be the best time to review a piece of information in order to promote long-term retention.

Try your best to set aside a chunk of time each day to (a) review previously-learned cards and (b) learn new cards (if you have any new cards pending). Mnemosyne will take care of all the prompting and scheduling; you just have to sit down and go through the cards!

Studying for quizzes (using the cramming scheduler)

Let’s say that you need to study for an upcoming quiz. In this case you want to see all of the active cards, regardless of when they are scheduled. And you don’t want your responses to each card to be recorded by Mnemosyne, because that would mess up the long-term learning schedule for those cards.

In these situations you want to use Mnemosyne’s “Cramming Scheduler”. Go to Manage plugins… under Settings or Preferences, and enable the “Cramming scheduler”. While this plugin is active, all cards will be shown, and no scheduling information will be saved. When you are done studying for the quiz, don’t forget to go back and disable the Cramming scheduler.

Long term memorization

At a little over one thousand words, the DCC Latin Core Vocabulary is a substantial yet manageable list. My hope is that with the aid of Mnemosyne, we can make it as easy as possible for students to start memorizing these words.

The use of tags allows subsets of the Core Vocabulary to be enabled incrementally. For example, students can start with the CoreLatin::1-200 group of highest-frequency words. Once those are learned, they can activate the CoreLatin::201-500 group, and after that the CoreLatin::501-1000 group.

After cards are learned for the first time, however, Mnemosyne will continue to present them again for review; but each card will be presented at appropriate intervals. If students are diligent about taking a few minutes each day to review cards, they can easily make steady progress toward committing these words to long-term memory

Alex Lee (alexlee@fastmail.net) is a PhD candidate in Classics at the University of Chicago. He has a strong interest in Latin and Greek language pedagogy – in particular, the implications of language acquisition theory and the use of technology as an aid to teaching. His dissertation examines the argumentative and rhetorical function of images in Plato’s Republic.

My favourite commentary is R. Deryck Williams’ Aeneid, which dates from 1973 and is now published by the Bristol Classical Press. I think that the main reason that I love it is that it is the work of a man who himself loved Virgil both wisely and well. This love shines on every page. It is a deeply civilized edition, constantly slipping into quotations from English poetry which set the Aeneid in its place near the font of European literature. It is odd that, as reception gains a more and more firm foothold, editors have become increasingly uptight about including literary parallels from the Renaissance and later in their texts. Williams read the Aeneid once a year – each time, he used to say, wondering whether Aeneas would bring himself to abandon Dido – and his understanding of the poem as a whole informs the edition throughout.

My favourite commentary is R. Deryck Williams’ Aeneid, which dates from 1973 and is now published by the Bristol Classical Press. I think that the main reason that I love it is that it is the work of a man who himself loved Virgil both wisely and well. This love shines on every page. It is a deeply civilized edition, constantly slipping into quotations from English poetry which set the Aeneid in its place near the font of European literature. It is odd that, as reception gains a more and more firm foothold, editors have become increasingly uptight about including literary parallels from the Renaissance and later in their texts. Williams read the Aeneid once a year – each time, he used to say, wondering whether Aeneas would bring himself to abandon Dido – and his understanding of the poem as a whole informs the edition throughout.