The DCC Core Latin and Greek Vocabularies are now available in Polish translation, thanks to the efforts of a wonderful Association of Classical teachers called Ship of Phaeacians. They can be followed on Twitter at @statekfeakow . The work was carried out by Statek Feaków, Agnieszka Walczak, and Marcin Kołodziejczyk. Thanks are due to them, and also to our Drupal developer Ryan Burke, who made the translation module work so that all translations can be linked to the same nodes, and created the views. This is the second of our international collaborations for translating the core vocabularies. The Greek core is already available in Portuguese thanks to Caio Camargo. Next month we plan to put up the Chinese translations as well, following the DCC seminar in Shanghai June 12-14. Would you like to help create a new translation in another modern language? Please let us know!

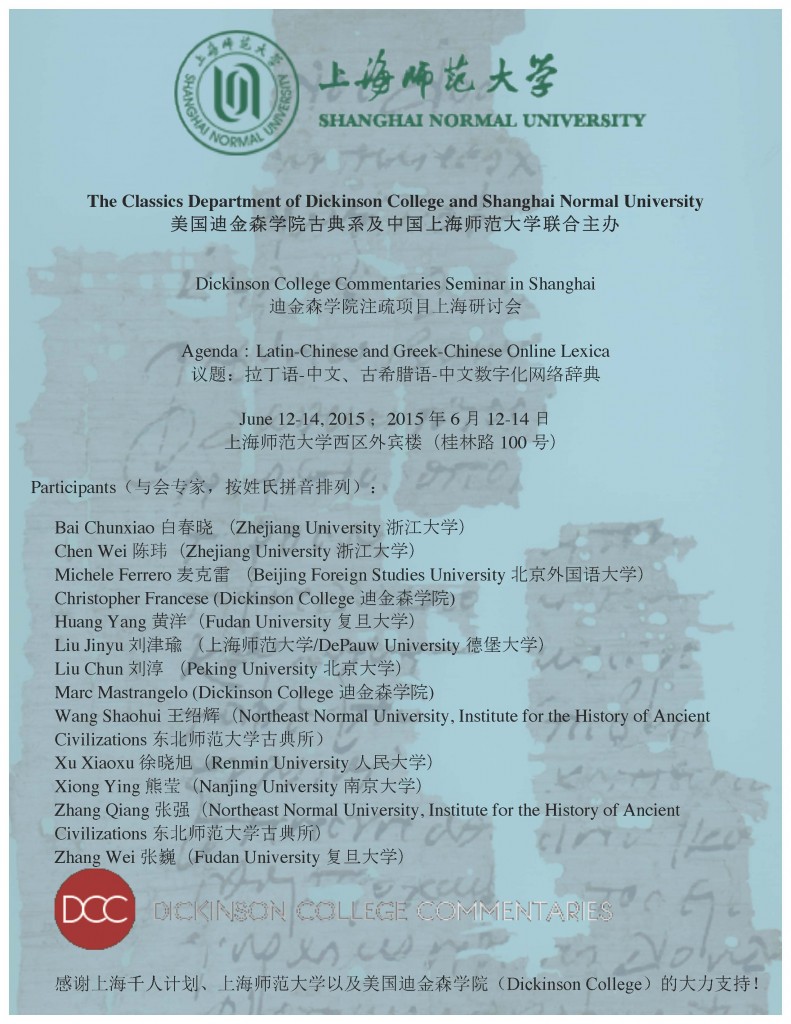

DCC Shanghai Seminar June 12-14

A stellar line up of Chinese scholars of the western classical tradition will meet in Shanghai next month to create Latin-Chinese and Greek-Chinese versions of the DCC Core vocabularies, and to form a plan for future collaboration and resource creation. Can’t wait! Thanks to Jinyu Liu of DePauw University for coordinating the event, and Shanghai Normal University for hosting!

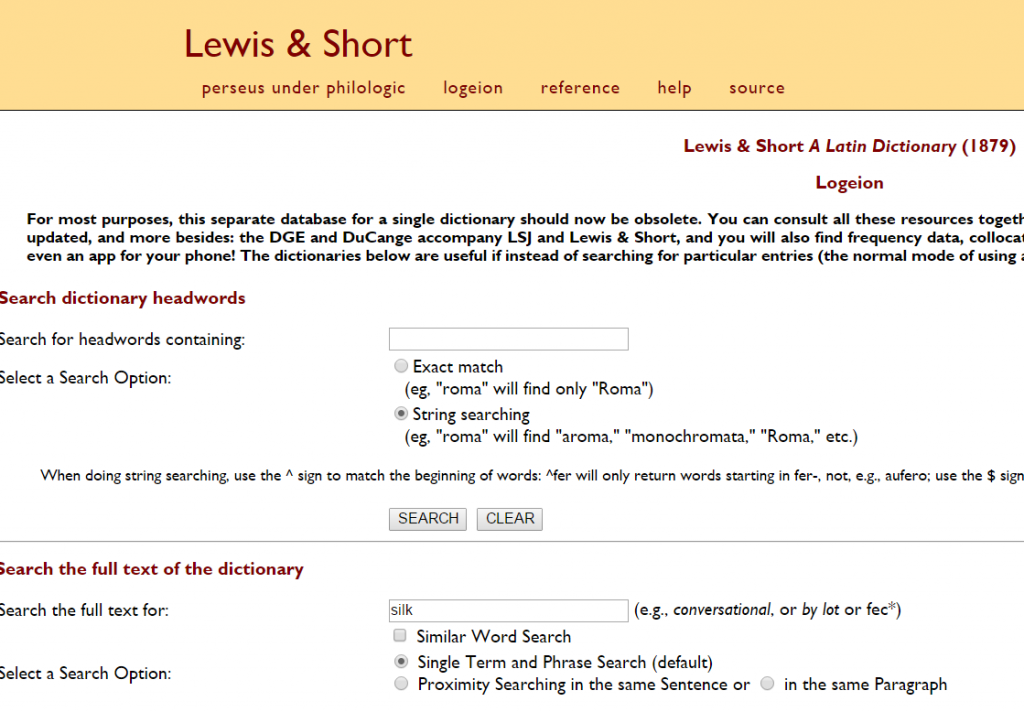

Searching in Lewis and Short

A little known but extremely useful resource for Latin composition is the digitization of Lewis & Short done at the University of Chicago:

http://perseus.uchicago.edu/Reference/lewis.html

Search the FULL TEXT of this dictionary for an English word to find every entry in Lewis & Short where that English word appears. Sort through the various Latin words that pop up until you find one that approximates what you want to say.

For example, a search for “silk” yields the following cornucopia of terms, all classically attested, or at least attested within the generous limits of L&S.

- birrus n., Aug. Serm. Divers. 49), = πυρρός (of yellow color), a cloak to keep off rain (made of silk or wool)

- bombycinus , a, um, adj. bombyx, of silk, silken (cf. sericus): vestis, Plin. 11, 22, 26, § 76: panniculus,

- bombycinus (page 243) 14, 24; Dig. 34, 2, 23, § 1.—Subst.: bombȳcĭna, ōrum, n., silk garments, Mart. 11, 50, 5; 8, 68, 7; App. M. 8, p. 214, 6.—And

- bombycinus (page 243) 11, 50, 5; 8, 68, 7; App. M. 8, p. 214, 6.—And bombȳcĭnum, i, n., a silk texture or web, Isid. Orig. 19, 22, 13. bombylis , is,

- bombyx (page 243) (f., Plin. 11, 23, 27; Tert. Pall. 3), = βόμβυξ. The silk-worm, Plin. 11, 22, 25, § 75 sqq.; Mart. 8, 33, 16; Serv. ad Verg. G. 2,

- bombyx (page 243) Verg. G. 2, 121; Isid. Orig. 12, 5, 8; 19, 27, 5.— Meton. That which is made of silk, a silken garment, silk: Arabius, Arabian (the best), Prop. 2, 3, 15: Assyria bombyx,

- bombyx (page 243) Orig. 12, 5, 8; 19, 27, 5.— Meton. That which is made of silk, a silken garment, silk: Arabius, Arabian (the best), Prop. 2, 3, 15: Assyria bombyx, Plin. 11, 23, 27, §

- holosericus (page 859) holosericus , a, um, adj., = ὁλοσηρικός, all of silk: vestis, Lampr. Heliog. 20; Vop. Aur. 45; id. Tac. 10; Cod. Th. 15, 9, 1. —Collat. form,

- metaxa (page 1140) metaxa or mătaxa, ae, f., = μέταξα and μάταξα, raw silk, the web of silkworms. Lit., Dig. 39, 4, 16; Cod. Just. 11, 7,

- necydalus (page 1196) necydalus , i, m., = νεκύδαλος (deathlike), the larva of the silk-worm, in the stage of metamorphosis preceding that in which it receives the name of bombyx: primum eruca fit, deinde, quod vocatur bombylius, ex eo necydalus, ex hoc in sex mensibus bombyx,

- Seres (page 1678) 11, 27, 11; Claud. in Eutr. 2.— sērĭ-cum, i, n., Seric stuff, silk, Amm. 23, 6, 67; Sol. 50; cf. Isid. Orig. 19, 17, 6; 19, 27, 5;

- sericarius (page 1678) or belonging to silks: textor, Firm. Math. 8: NEGOCIATOR, Inscr. Orell. 1368; 4252.—As substt. SERICARII, silk- dealers, Inscr. Fabr. p. 713, 346.— SERICARIA, ae, f., a slave who took care of silk, Inscr. Orell.

- sericarius (page 1678) SERICARII, silk- dealers, Inscr. Fabr. p. 713, 346.— SERICARIA, ae, f., a slave who took care of silk, Inscr. Orell. 2955. sericatus , a, um, adj.

- sericoblatta (page 1679) sericoblatta , ae, f. Sericus, a garment of purple silk, Cod. Just. 11, 8, 10; Cod. Th. 10, 20, 13; 10, 20, 18. sericum , i,

- vellus (page 1965) Calp. Ecl. 2, 7.— Of woolly material. Wool, down: velleraque ut foliis depectant tenuia Seres, i. e. the fleeces or flocks of silk, Verg. G. 2, 121.— Of light, fleecy clouds: tenuia nec lanae per caelum vellera ferri,

English search is not, I believe, available on Logeion, which is the successor to this site. Hopefully this older one will be kept around for a good while longer. I don’t know anything as good online for searching in English for Latin words. Thanks to Helma Dik and the U. Chicago team for all their work!

Learning from older school editions of classical texts

Here is my talk from CAMWS 2015 on digital text annotation, for those many who were unable or disinclined to come to an 8:00 p.m. (!) session. Please leave a comment if you like.

The field of digital classics is very focused right now on the unsolved problem of how to present scholarly editions of Latin and Greek texts online, and in particular how to represent the apparatus criticus and link to manuscript evidence. Not enough attention, I would suggest, has been paid to the question of how to best present classical texts for ordinary students and readers of Latin and Greek in the digital realm.

Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae, Book 1, ed. Max Bänziger (Monumenta Informatik) with links to manuscripts and citation links. http://monumenta.ch/latein/

A deluge of plain text is not going to do it, I think we would all agree. Readers and learners typically want to know “what does this word mean?” and “what’s going on with the grammar here?” Plain digitized texts, or texts enhanced with links to manuscript images like this one provide no guidance on these matters, since they are designed for advanced scholars.

The main focus in tool development for readers to deal with these questions has been automatic parsers linked to dictionaries, like nodictionaries.com, the Alpheios plugin, or the Perseus Word Study Tool. But the unreliability of those tools, not to mention their perceived role as crutches, has given them a poor reputation among teachers and thoughtful students alike.

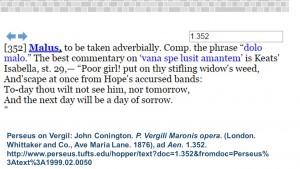

Perseus on Vergil: John Conington. P. Vergili Maronis opera. (London. Whittaker and Co., Ave Maria Lane. 1876), ad Aen. 1.352.

Another tack has been to digitize older, public domain commentaries like Conington’s Vergil. Perseus includes several such works. But whatever the merits of these works in their day, they are often opaque to learners and readers now. Older commentators tend to assume an audience that has already been well-trained in Latin, and just needs a little reminder of a common construction, or might enjoy an apposite quotation from Keats.

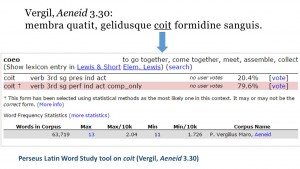

The Perseus Word Study tool is designed to provide more basic information. It does its best to guess which dictionary head word a given form derives from, then gives a brief definition, with links to Lewis & Short, and a series of suggested parsings. It guesses the correct parsing based on frequency, and includes a voting feature that lets you select which parsing you think is best, and what definition you think best for the context.

This voting feature is slowly improving the accuracy of the Word Study Tool, but even if the parsing happens to be right (which it is not in this particular case), the dictionary data itself is often not helpful, because the choices are the very brief “short defs” and the full fire hose of Lewis & Short.

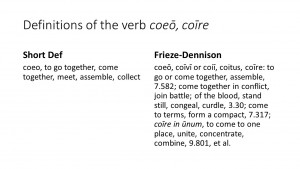

A good but under-used solution to this problem of too little or too much is the author-specific dictionary of the type that is contained in many older school editions, such as Henry Simmons Frieze’s editions of the works of Vergil.

This is his version of the Aeneid, revised in 1902 by Walter Dennison. Freize published a full dictionary to all the works of Vergil in various revisions over the 1880s and 90s, and Dennison revised it slightly to focus on the Aeneid material only for this edition.

Note that Frieze includes all the principal parts, with macrons; a number of Vergilian definitions not included in the Short Def, and citations for all the particular senses. Frieze spent his career at the University of Michigan teaching Vergil and other Latin authors, and working on his Vergil editions. His translations are expert, and his philological acumen at a very high standard.

Frieze does equally well in the sphere of proper names, where automatic tools are often helpless to distinguish between homonymous figures. This is precious intelligence for readers of Vergil. In 2014 I set out to properly digitize Frieze’s Vergilian dictionary with the ultimate goal of creating running vocabulary lists for the whole Aeneid.

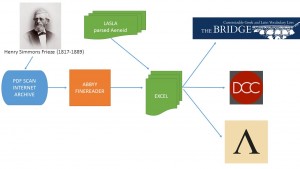

The process went as follows. The .pdf scan from the Internet Archive went through a OCR program called ABBYY Finereader. The resulting text went into an Excel spreadsheet. To Frieze’s definitions we added frequency data derived from a human inspection and analysis of every word in the Aeneid. This work was carried out by teams at the Laboratoire d’Analyse Statistique des Langues Anciennes (LASLA) at the Université de Liège in Belgium.

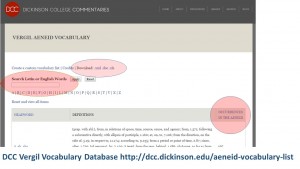

Once this process was complete and the spreadsheet made, it was uploaded into Drupal, where the database version on DCC can now be searched, ordered by frequency, and downloaded in various formats. It can be reused at will under a Creative Commons license. It will also form the basis for the running lists in our edition of the Aeneid now in development.

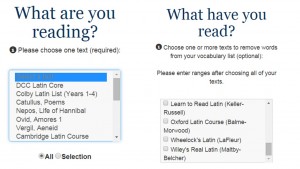

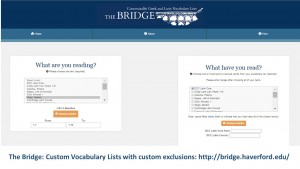

The Bridge, developed at Haverford, allows the making of accurate vocabulary lists for custom ranges of text

Putting the information in a spreadsheet keyed to LASLA lemmata made it possible to share with The Bridge, a new tool developed by Bret Mulligan at Haverford College. This allows the user to specify a particular line range and get vocabulary lists, either all words, or with certain words excluded, like the DCC Core vocabulary, or the vocabulary of a common introductory textbook.

The important thing to emphasize is that the lists include not the headwords that are statistically likely to appear in the passage, but (barring minor textual difficulties) those that actually do, and no others. I also put a column in the spreadsheet listing the headwords as used by Logeion, and thanks to Helma Dik is it also available there.

The facilities are now starting to exist by which accurate lexical information such as this can be shared by the community of classicists, and the Bridge and Logeion are in the vanguard of this development. By excavating and reclaiming more author-specific dictionaries we can all contribute to this positive change and get the resources that students and readers need. Effective digitization of older hand-made tools can be more effective than the creation of new automatic tools.

II. Goodell’s Greek Grammar

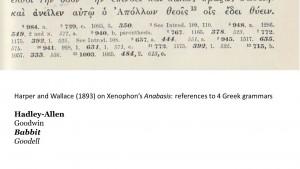

Harper and Wallace’s edition of the Anabasis annotates with references to four different school grammars

Perseus cross-references to grammars: not tied to specific words, and pointing to advanced grammars only

Another nice feature of older school editions that can be usefully recuperated in the digital realm is reference to grammars. A learner or reader is likely to ask, what’s going on with the grammar in this passage? What rule covers this? Or is it somehow exceptional? This question was sometimes dealt with in older school editions by simply giving a citation from a widely-used grammar book–or to four of them, as in the case of Harper and Wallace’s edition of Xenophon’s Anabasis–and relying on the student to go look it up. In olden days, perhaps they did. The internet allows for much easier cross-referencing of this kind. Sometimes Perseus operates in this way, as with T. Rice Holmes’ Caesar Gallic War, Perseus makes the cross-references clickable.

More common in Perseus is a kind of general reference to grammars for an entire page, typically to a large discussion of “the tenses” or “the cases.” Here we see a page of Thucydides with references to Smyth’s discussion of the article, and the cases, and similar links Kühner-Gerth, and Goodwin’s Moods and Tenses. None of this is keyed to a particular word or phrase in the text. Another issue here is that all the Greek grammars at Perseus are advanced.

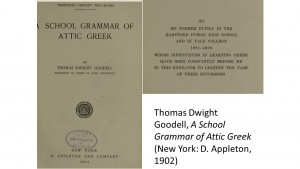

In fact none of the more elementary Greek grammars like those referred to by Harper and Wallace have been digitized properly, to my knowledge. While reading Harper and Wallace’s edition of the Anabasis two summer ago I became aware of Thomas Dwight Goodell’s excellent School Grammar of Attic Greek (1902), whose dedication speaks to the attitude of a gifted teacher.

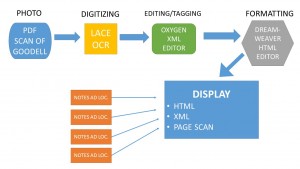

With help from Bruce Robertson at Mount Allison University and some of my students I set about digitizing Goodell. This involved the hand-correction and tagging of the raw OCR output provided by Robertson’s Lace, which in turn went back into Lace and improved its accuracy. This corrected output was then tagged in XML using Oxygen, and converted into html. The html pages were edited by Meagan Ayer, and the navigation created by Ryan Burke at Dickinson.

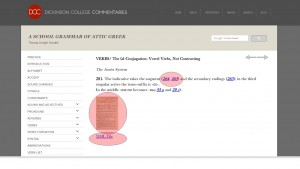

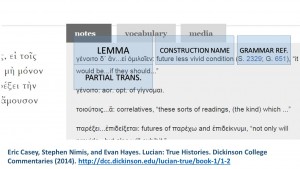

Now we have an easily navigated, attractive Greek grammar, including page images, downloadable XML, and linked cross-references. We can now link directly to that in the notes fields of DCC.

The aim here is to simplify annotation, and obviate the need to re-explain grammatical features. It has the pedagogical value of not being a crutch, in that the reader must make his or her own connection between the passage at hand and the relevant rule. The typical annotation of this type has four elements: the lemma, the name of the construction, the grammar cross-reference, and a partial translation. One could remove the second and fourth of these elements.

The internet has made all of us potential publishers, and there are many classical teachers out there creating resources for their own students and sharing them with the world. The future, I believe, lies in collaboration, but not just collaboration between ourselves. We should also open ourselves to collaboration with men like Henry Simmons Frieze and Thomas Dwight Goodell, and adapt their durable work to the needs of contemporary readers and students.

Liberating the Text

Gregory Crane has written a fierce new manifesto directed at editors of classical texts, in which he urges scholars to “liberate textual data from corporate control” by publishing editions only in open (Creative Commons) licensed venues and only in TEI-XML tagged formats, thus making them interoperable and freely accessible to a global audience. He laments the lack of progress in this direction, noting that TEI encoding has been around since the 1980s, and open licenses since the 1990s. The main culprit, he says, is academic politics, and the perceived need to publish under an established university press to receive formal academic credit. The publishing of critical texts only in book form is “preventing Classical Greek and Latin from shifting to a fully open intellectual ecosystem.”

The solution he proposes is for scholarly editors to publish their work themselves:

If editors wish to work on their own to create editions of Greek and Latin texts, they should buy a TEI-aware XML editor and learn how to produce a modern edition. Anyone smart enough to edit an edition of Greek and Latin is smart enough to understand the necessary TEI XML.

Why TEI? Working in interoperable TEI XML will allow for competing editions to be compared:

Here the goal is to have as many TEI XML transcriptions as possible and to help researchers visualize the degree to which different editions differ and to be able to compare different editions.

The ideal of a universal, interoperable apparatus criticus that collates all textual variants and conjectures of scholars based on existing print editions is probably, he admits, an unattainable one. He argues instead for a more pragmatic approach to apparatus, one that allows for word search that links to page images of the original print resources:

Here our goal is to have a maximally clean searchable text but not to add substantive TEI XML markup that captures the structure of the textual notes — the structure of these notes tend to be complicated and inconsistent. Our pragmatic goal is to support “image front searching,” so that scholars can find words in the textual notes and then see the original page images.

Another proposal is to create a series of open-licensed textual commentaries that collate the textual variants that are deemed most significant:

Strategy one: Support advanced graduate students and a handful of supervisory faculty to go through reviews of recent editions, identifying those editorial decisions that were deemed most significant. The output of this work would be an initial CC-BY-SA series of machine-actionable commentaries that could automatically flag all passages in the CC-BY-SA editions where copyrighted editions made significant decisions. In effect, we would be creating a new textual review series. Because the textual commentaries would be open and available under a CC-BY-SA, members of the community could suggest additions to them or create new expanded versions or create completely new, but interoperable, textual commentaries that could be linked to the CC-BY-SA texts. Here the goal is to create an initial set of data about textual decisions in copyrighted editions and a framework that members of the community can extend.

Crane imagines the objection that all this infrastructure is not really needed, since those who use critical editions of classical texts have access to all that they need, and that nobody else really needs scholarly critical editions of classical authors. But this view he sees as essentially suicidal for advanced research that is publicly funded:

If we think that specialists at well-funded academic institutions alone need access to the best textual data, we should express that position clearly so that the federally funded agencies and private foundations know where we stand.

Rather, scholars have an obligation (the word occurs four times) to share their ultimately public-funded work with the public that has ultimately paid for it. The driving force behind this passionately argued essay is a profound sense of duty, a commitment to “our obligation as humanists to advance the intellectual life of humanity.”

My questions and comments are as follows:

- As someone dedicated to creating high quality CC-BY-SA digital commentaries on classical texts I applaud the vision, clarity, and passion of this essay. I believe with Crane that, as he has expressed in other venues, digitization is philology in the truest and highest sense. Digitization is a central intellectual and (again, Crane is correct) moral challenge facing our profession right now. If his essay shakes loose a few more philologists from unthinking acquiescence in the status quo, then it will be a victory.

- Why are scholarly editions and apparatus criticus the highest priority? Why not work on wresting better translations and commentaries from copyright, and from the brains of working scholars? Though I hesitate to say it for fear of being seen as lacking scholarly seriousness, we already have digitized texts that are good enough for most purposes, and for most authors significant textual issues can usually be dealt with in the context of an explanatory commentary. There is a significant need for new translations, however. For example, neither Livy nor Polybius have ever been translated into Chinese. This means that two of the seminal and central texts for the study of the Roman Republic are simply not available at all to a large portion of humanity. Even in the much better-served realm of English, public domain translations are often all but unreadable, if not downright misleading. Why not direct some funding and some of the scholarly energies of classicists in that direction?

- If we can think of the translation audience as the biggest and (arguably) most important circle, then the next concentric audience ring must be ancient language learners. What this group needs above all are well annotated editions with linguistic explanations, interpretations, and links to grammatical and historical reference works. One of the best ways for classical scholars to fulfil their duty to openly disseminate their findings would be to apply those findings to texts, summarizing research findings found in articles and monographs and making them directly relevant to the serious students who take the time to work their way through a dialogue of Plato or a book of Homer in Greek or a speech of Cicero in Latin. Existing open resources for this are woefully inadequate.

- Finally, if we progress to the innermost circle of textual editors and research scholars, I would like to have some more specificity and examples of the ways in which TEI-XML will allow for interoperability. A recent article in the Journal of TEI by the classically trained Desmond Schmidt suggested that true interoperability of digital scholarly editions via TEI is not really possible, given the subjectivity of tagging. But even if we can all stick strictly to the EpiDoc standards, how does this benefit us in practice? Can we see an example of a pair of correctly tagged editions of the same text from different sources, and what what benefit this interoperability provides? It seems that the minimal tag set proposed for apparatus criticus in the current EpiDoc standards for external apparatus criticus should make this theoretically feasible. But when it comes to in-line commentary, to the actual connecting of a scholarly discourse to a particular passage in a classical text via TEI-XML, the EpiDoc guidelines are a stub. And in the XML tagged commentaries on Perseus, like that of Greenough et al. on Caesar’s Gallic War, there doesn’t seem to be any clear interoperable linking with the Latin text itself. But maybe I’m misunderstanding the tags. I would love to be able to see a few examples of TEI-compliant commentaries on classical texts, and then a demonstration of how the effort needed to produce such bears actual fruit. Then I would consider the large investment of time and money required to put the DCC commentaries into TEI-XML.

Thank you, Dr. Crane, for this bracing and inspiring essay!

Goodell’s School Grammar of Attic Greek

In an earlier post I bemoaned the lack of a fully digitized school grammar of ancient Greek, and kvetched that the existing Greek grammars digitized at Perseus lack something important, namely, the English index to those works. The index is how most of us consult Greek grammars, and this lack, combined with an occasionally dodgy search capability in Smyth apud Perseus, made it seem desirable to fully digitize a good Greek grammar, including the index. We chose one that is I suspect much better for learners than Smyth, and now I am proud to say that it is done and up.

May I present to you Thomas Dwight Goodell, A School Grammar of Attic Greek (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1902). Goodell’s orientation is nicely seen in the dedication of the book:

The content, with its judicious selection of detail and clear explanations, shows the dedication of a gifted teacher.

The original scan came from the Internet Archive. Our version was created in 2013–2014 with support from the Roberts Fund for Classical Studies and the Mellon Fund for Digital Humanities at Dickinson College. Bruce Robertson of Mont Allison University performed the OCR using Rigaudon, the output of which is available on Lace. At Dickinson the OCR output was edited and the XML and HTML pages created by Christina Errico. Ryan Burke created the web interface, and Meagan Ayer edited and corrected the HTML pages. The content is freely available for re-use under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license.

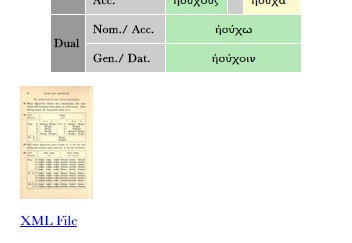

I hope you can find some use in it. Each section is given its own page, which results in widely different lengths of pages, and also sometimes some inconvenience when a single topic is covered over many chapters. On the other hand, we included page images at the foot of every page to allow you to look over several chapters at once, and also to check the accuracy of the transcription. The pages are also available as XML.

Page images are available as clickable thumbnails at the foot of the page, and there is a link to an XML version.

Navigation is via the English or Greek index, by chapter, or by full text search.

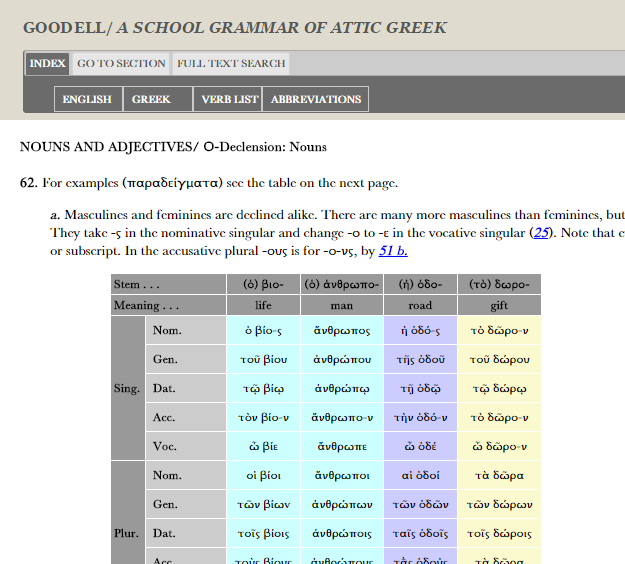

Megan Ayer made a few alterations to the original text. She corrected small typos, clarified abbreviations, and created tables in html with unobtrusive color coding to aid in readability.

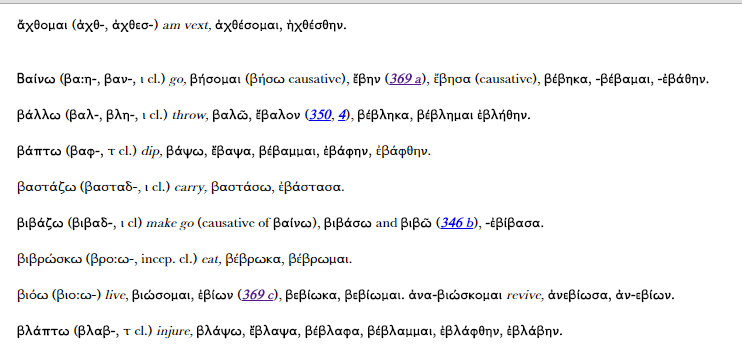

Another nice feature is the verb list, a quite extensive list of principle parts, with hyper links to further discussion elsewhere in the book. The font, New Athena, was likewise chosen for readability. Normally we would have used Cardo, but the issue with the character “rho + rough breathing” in Cardo has still not been resolved.

We made the decision not to put this content into Drupal, essentially for reasons of cost. I see the desirability of a Drupal-based Greek grammar, and someday we may be able to achieve it, but for now it is straight html.

Though the content has been carefully edited, there may be errors or infelicities, and I would be most grateful to be notified. Please comment here if you have suggestions, or shoot me an email.

A New Latin Macronizer

Felipe Vogel has released a new Latin macronizer, Maccer, and I thought I would take it for a spin and share the results. It works based on a database of previously macronized Latin texts (some provided by DCC), and is still in development.

For my test I figured I would use an unusual text I have been working on lately, Historiarum Indicarum Libri XVI, about the Portuguese exploration of the Far East in the 16th century. It was published by the Jesuit humanist Pietro Maffei in 1588, and the Latin is excellent and full of interest. Book 6 is a fascinating ethnography of China, informed by reports from Jesuit missionaries who visited and lived in China over a number of years. The last print edition was 1751: Joannis Petri Maffeii Bergomatis E Societate Jesu Historiarum Indicarum Libri XVI (Vienna: Bernardi, 1751), and thanks to a tip from Terence Tunberg (who introduced me to this text) I tracked it down on the site of the Dresden Library. Since there is no fully digitized text, my students and I transcribed Book 6 this past fall. Here is an excerpt, with no macrons.

E Sinarum provinciis maxime occidua est Cantonia. Eo priusquam pervenias, multae occurrunt insulae; quas praefecti regii praesidiis et classibus tenent: neque ipsorum iniussu progredi advenas Cantonem est fas. Fernandus Andradius, ut exponere coeperam, cum ad Tamum insulam pervenisset, post diuturnam moram, transitu aegre tandem impetrato, cum duobus expeditis et egregie ornatis navigiis, cetera classe ad Tamum relicta, Cantonis portum invehitur, ac magistratuum permissu Thomam legatum exponit, cui aedes et lautia de more attributa. Ibi Fernandus, mira lenitate ac iustitia contrahendo cum incolis, haud ita difficili negotio aditum ad ea commercia nostris aperuit.

With Vogel’s macronizer this becomes

Ē ✖Sinarum prōvinciīs maximē ✖occidua ✪est ✖Cantonia. Eō priusquam perveniās, multae occurrunt īnsulae; quās ✖praefecti ✖regii praesidiīs et classibus tenent: neque ipsōrum ❡iniussū prōgredī ✖advenas ✖Cantonem ✪est fās. ✖Fernandus ✖Andradius, ut expōnere ✖coeperam, cum ad ✖Tamum īnsulam pervēnisset, post diūturnam moram, trānsitū aegrē tandem ✖impetrato, cum duōbus expedītīs et ēgregiē ✖ornatis nāvigiīs, cētera classe ad ✖Tamum ✪relictā, ✖Cantonis portum invehitur, ac magistrātuum ❡permissū ✖Thomam lēgātum expōnit, cui aedēs et ✖lautia dē mōre ❡attribūta. Ibi ✖Fernandus, ✒mīrã ✖lenitate ac iūstitia ✖contrahendo cum incolīs, haud ita ✖difficili negōtiō aditum ad ✒eã commercia nostrīs aperuit.

The symbols mean this:

| ✖ | unknown word, i.e. not yet in Vogel’s database. |

| ✒ | ambiguous: uncertain vowels marked with a tilde (~). |

| ✪ | guessed based on frequency. |

| ❡ | prefix or enclitic detected attached to a known word. |

| ☛ | invalid characters detected. |

I made sixteen corrections in 92 words.

21 words were flagged as unknown, 10 of those were proper names (Sinārum, occidua, Cantonia, praefectī, regiī, advenās, Cantonem, Fernandus, Andradius, coeperam, Tamum, impetrātā, ornātīs, Tamum, Cantonis, Thomam, lautia, Fernandus, lēnitāte, contrahendō, difficilī). I made 9 corrections in that group, leaving alone most of the proper names for now.

3 words were guessed based on frequency, all correctly (est, est, relictā).

3 words were marked as “prefix detected,” all correctly macronized (iniussū, permissū, attribūta)

2 were marked as having invalid characters (mīrā, ea), had tildes over the vowel, and had to be corrected by hand.

Only two words were incorrect but not flagged as in any way problematic (cēterā, iūstitiā). In both cases it was an ambiguous first-declension -a. The other vowels in those words were correct.

The hand-corrected result is as follows:

Ē Sinārum prōvinciīs maximē occidua est Cantonia. Eō priusquam perveniās, multae occurrunt īnsulae; quās praefectī regiī praesidiīs et classibus tenent: neque ipsōrum iniussū prōgredī advenās Cantonem est fās. Fernandus Andradius, ut expōnere coeperam, cum ad Tamum īnsulam pervēnisset, post diūturnam moram, trānsitū aegrē tandem impetrātā, cum duōbus expedītīs et ēgregiē ornātīs nāvigiīs, cēterā classe ad Tamum relictā, Cantonis portum invehitur, ac magistrātuum permissū Thomam lēgātum expōnit, cui aedēs et lautia dē mōre attribūta. Ibi Fernandus, mīrā lēnitāte ac iūstitiā contrahendō cum incolīs, haud ita difficilī negōtiō aditum ad ea commercia nostrīs aperuit.

I would call this very good results, and it should be possible to do even better given a larger database. In theory we could do even better than that by marrying a parser and a dictionary like LaNe that has quantities accurately marked. If all goes well I hope to embark on such a project this fall with the help of a Dickinson Computer Science senior student. The other thing I would like to see is an editing environment that would make inserting macrons as easy as clicking on the vowel. This would really help in the inevitable process of hand correction.

Thank you Felipe, for this amazing tool!

Exporting and Sharing Digital Scholarly Editions

Desmond Schmidt’s recent article in the Journal of TEI about how to create a truly portable and interoperable digital scholarly editions came at an opportune time for me. DCC is entering into a relationship with Open Book Publishers in Cambridge to exchange our (Creative Commons licensed) content. They will publish some of our commentaries as books and eBooks, and we will publish some of their book commentaries as multimedia, web-based editions. But how to actually make the transference?

We are starting by delivering Bret Mulligan’s commentary on Nepos’ Life of Hannibal. OBP needs it in a format they can use and set in InDesign and publish in EPUB. But how should the transfer happen? How can we actually share the open licensed scholarly content of DCC so it can actually be re-purposed and pe-published in different formats? Not easily, it turns out. Our commentaries are just html pages in Drupal, not XML based and TEI tagged documents, and thus, in the view of one early critic of the project, “not truly digital.” XML-TEI is intended as a universal standard for editing and tagging documents of all kinds, and not adopting that for our project was at the time a decision based on cost. Anyway, after various investigations on the OBP side it turned out the best way for us to get our commentaries is to OBP deliver the via . . . wait for it . . . Microsoft Word–with all the labor and possibilities for error that that involves.

Wouldn’t things be better if our texts were marked up in XML-TEI? No, according to Schmidt. He argues, in effect, that TEI is actually hindering the sharing of digital scholarly editions. The problem is the subjectivity of TEI tagging and the diversity of the tags themselves, which in Schmidt’s view makes true interoperability of scholarly editions in TEI a pipe dream. The solution he proposes, as I understand it, is to get all the tags and metadata out completely and into separate files, preserving the text as plain text (in multiple versions if we are dealing with revisions or variants). He is evidently developing an editing environment which ends up creating zipped files that completely separate the text itself, annotation data that points back to the text, and metadata. A few choice quotes:

Syd Bauman (2011), one of the original editors of TEI P5, has since observed that interoperability of TEI-encoded texts today—that is, the exchange of unmodified TEI files between different programs—is “impossible.” (9)

One obvious remedy to this problem is to remove the main source of non-interoperability, namely the embedded markup itself, from the text. By removing it, the part which contains all the significant interpretation can later be added or substituted at will. (21)

What remains when the markup is removed is a residue of plain text that is highly interoperable, which can be exchanged with other researchers, just as the files on Gutenberg.org are downloaded by the tens of thousands every day (Leibert 2008). However, if one suggests this to someone who regularly uses TEI-XML, the immediate objection is made that this will solve nothing, because even plain ASCII texts are still an interpretation of what the transcriber sees on the page (e.g. Sperberg-McQueen 1991, 35). This point, although valid to a degree, misses an important distinction. (22)

And it goes on in this interesting vein. I would love to hear from people who are wiser and more experienced than I am about Schmidt’s critique of embedded TEI annotation and his proposed solution. In the meantime, I need to go format some stuff in Microsoft Word.

Dickinson College Commentaries Seminar in Shanghai, June 2015

I am pleased to announce the very first DCC seminar in China, to be held in Shanghai, June 12–14, 2015. The event will be hosted by Shanghai Normal University and is being organized by Marc Mastrangelo, Professor of Classical Studies at Dickinson, and Jinyu Liu, Associate Professor of Classical Studies and Chair of the Classical Studies Department at DePauw University. Prof. Liu also holds the title of Shanghai “1000 plan” Expert/Distinguished Guest Professor at Shanghai Normal University.

The event will bring together Chinese scholars of the western classics around a project to create Chinese version of the Dickinson College Commentaries websites. The plan is to begin by producing a Mandarin version of our core vocabularies for Latin and Greek, with the hope of stimulating more wide-ranging collaborations in the future. In addition to Professors Mastrangelo, Liu, and myself, participating scholars will include Liu Chun (Peking University), Chen Wei (Zhejiang University), Bai Chunxiao (Zhejiang University), Huang Yang (Fudan University), Zhang Wei (Fudan University), Wang Shaohui (Northeast Normal University, Institute for the History of Ancient Civilizations), and Xiong Ying (Nanjing University).

The inspiration for the project was a fascinating panel at the APA (2014), “Classics and Reaction: Modern China Confronts the Ancient West,” in which scholars from both North America and China (including Prof. Liu) describe the current flowering of the western classics in China, while also explaining the limitations of available resources.

We hope that a Chinese DCC will provide resources, for free and in Chinese, but also create a space for collaboration between Chinese and Western classical scholars. A Chinese DCC could provide free access to high quality scholarly resources for Chinese speakers who want to engage with western classical texts directly, both through translations and in the original, with Greek-Chinese and Latin-Chinese vocabularies, and interpretive notes on individual passages.

Generous support for the seminar is being provided by Dickinson College, The Roberts Fund for Classical Studies, Shanghai Normal University, and DePauw University.

Fall Colloquium for Classical Culture Dickinson College

The Delta Theta chapter of Eta Sigma Phi at Dickinson College invites contributions for the inaugural Fall Colloquium for Classical Culture, taking place on December 5, 2014 at Dickinson Classical Studies Department. All undergraduate students are welcome to participate.

The colloquium is intended to provide the opportunity to present original research on any aspect of the ancient Greek and Roman world (e.g., language, literature, art, archaeology, history, religion, philosophy, or reception). These papers may be drawn from new work, but students are also encouraged to submit papers written in previous semesters. This is an excellent opportunity to learn how to present your own scholarly work, field questions, and gain positive feedback. Furthermore, it is the hope of the organizers that students who participate will submit an abstract to the national Eta Sigma Phi undergraduate conference, which will take place in April, 2015 at Richard Stockton College.

Students should submit an abstract (no more than 250 words) to Lucy McInerney (mcinernl@dickinson.edu) by 5:00 p.m. Monday, November 24, 2014.

In the abstract, students should state the question they intend to investigate, what body of evidence they will use, and what conclusion(s) they will draw.

Each student will have 10 minutes to present the papers, and a question and answer period will follow each presentation.

Eta Sigma Phi, founded in 1914 at the University of Chicago, is a national classics honorary society for students of Latin and/or Greek who attend accredited liberal arts colleges and universities in the United States. The Delta Theta chapter has been active for many years, and is excited to host this first Fall Colloquium for Classical Culture.