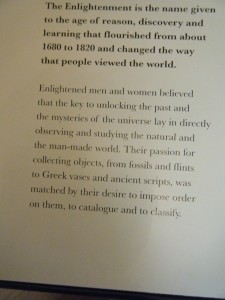

A plaque in the British Museum tells us, “Enlightened men and women believed that the key to unlocking the past and the mysteries of the universe lay in directly observing and studying the natural and the man-made world. Their passion for collecting objects, from fossils and flints to Greek cases and ancient scripts, was matched by their desire to impose order on them, to catalogue and to classify”. Let’s put on our mathematics hats on and visit the transitive property for a second. Math isn’t my strong suit but I think it works. People from the Enlightenment believed in prospering and discovering more about the world around them by collecting ideas from others. The English people have prospered and discovered more about the world around them by collecting ideas (and goods as demonstrated in the museum itself) from others. Can we not substitute the English for the people in the Enlightenment then? By my understanding of the transitive property we can. And if we do that, the British Museum puts the British people on display fantastically.

Signage in the Enlightenment room

Our class seems to be throwing around ideas about how British the British Museum really is. I’ll try to give the topic as good a go as the rest of the class has done. I think the British Museum is actually the perfect name for a museum that showcases a country that has borrowed or stolen ideas from other cultures from which they can prosper by showcasing artifacts that they have borrowed or stolen from other cultures from which they prosper. That’s an incredibly wordy way to say that the name fits because Britain itself is a lot like the exhibits the museum has: a forum of borrowed ideas and items. Not convinced? Look around at the people who are at the museum. First off, it’s incredibly crowded. Good luck getting through to see the Rosetta Stone, Cleopatra’s artifacts, the Easter Island statue, or the dancing Shiva. The crowd doesn’t simply consist of British people admiring what they have taken from other cultures. Walk through the crowd and listen to all the different languages that surround you. Chinese, Japanese, Russian, French, something that sounds like Hebrew, and, of course, English- you name it, you’ll probably hear it. Aware of this, the museum offers all of those languages on all of its important postings so that everyone who visits can navigate the museum as easily as possible (which, due to its size, isn’t very possible despite the amounts of maps available for use). As soon as you step out of the museum, you see a hot dog stand and a macadamia nut vendor and feel very much in ‘British’ London. But look around at the surrounding shops and restaurants on surrounding streets. Again, there are multiple Chinese, Thai, Indian, French, and Middle Eastern places all within walking distance (if not eyeshot) of the museum. Not only are these populations present in Britain today but they have also been influential in British history for quite some time. We’ve discussed in group discussions how today’s Britain has been shaped by the colonies it’s imperialized, by the countries it’s traded with. For years, Britain has been formed by borrowing ideas from other countries- it only makes sense that the British Museum would be composed of the work of other countries as well. In that vein, the British Museum is incredibly British in my mind.

Just some of the languages listed on a sign reminding us not to touch what's on display

So if the museum is British and thus displays the British quite intensely, I’m interested in what the museum wants us to deduce from the exhibits. What does the museum think is British and how does it want to display the culture to us? Clearly, it wants visitors to see a culture that is rich in intellect, has an appreciation for the arts, and is open and proud of its diversity. I would argue that that is in line with what Britain wants to portray itself as to the world: a welcoming place in which diversity can thrive. As our last class discussion demonstrated, the success of that endeavor is debatable to say the least. But the museum at least strives to guide everyone through its walls in as equal a way as is possible by listing so many different languages on its signage. Maybe if we look hard enough, that same helping hand might be around the city as well. Maybe. Just don’t get swept away in the crowd while trying to spot such a sign.

1 response so far ↓

Brandon R. // Aug 31st 2009 at 05:20

I thought this was a great post, Audrey; it’s important to see this museum with regard to the British who designed and curated the exhibits.

I am not convinced that the guiding mantra of the museum was to gather these objects (I found there to be fewer instances of borrowed/stolen “ideas”) for the purpose of creating a distinctly British identity. At the time of this museum’s founding, Britain was at the height of its power. Surely they wanted to display this influence and power in the world, to the world. Or, at the very least, show the British public just how great their country could be. You could imagine the public wanting to become more “cultured” or “enlightened” by visiting this museum. They could look at places around the world to gain 1) some appreciation for diversity and 2) reinforce their pride for Britain’s exploits.

I will take a step back and mention the “Living and Dying” exhibit. This is about as close as I can get to agreeing that the British want to forego any self-righteousness and truly understand and compare different cultures from around the world. This exhibit discusses one topic (living and dying) and how it is understood by different societies around the world (including the BRITISH). That kind of face-to-face interaction proves the most effective, in my opinion.

Please let me know if you have any disputes with what I’m arguing. I think this is an important topic to grapple with and one that can be addressed from a multitude of lenses and perspectives.

(Again- really nice post!)

You must log in to post a comment.