The notion of ‘identity’ cannot be pinned down as having one definition. For the purpose of this post, I define identity as a socially and personally created label one can embody, shed, defend, create, and mold (not necessarily used at all–or at least not in this order). When used in terms of immigration, the presence of identity can move in one of many ways:

1. Relying on the Traditional and Comfortable

Mrs. Suri, one of the minor characters in Tarquin Hall’s Salaam Brick Lane resides in London, yet she remains solidly committed to the Indian views and traditions regarding marriage. She lives in a city among millions of people from all backgrounds. She does not adapt; she surrounds herself with the familiar. Some would confuse this with stubbornness. Committing to the comfortable is a choice you make when you reflect on your own identity. You can let outside perceptions to mold how you carry yourself, or you can resist. The latter results in a situation similar to that of Mrs. Suri. You stick to your identity you created for yourself long before immigrating to a new place defined by very different identifying features.

2. Voluntary Adaptation

The Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in London has in many ways voluntarily adapted itself as a modern place of worship set several thousand miles away from India and, more importantly, the Ganges River (one of, if not the most important site in Hinduism). They expect non-Hindu visitors to the mandir, as indicated by an extensive exhibit tracing the main tenets of the religion. Certainly, places like St. Paul’s or Westminster Abbey have taken on a revised role as a tourist attraction, but you will not find there a museum describing the history or practices of Christianity; that’s left for the history books. The massive Hindu temple stands out in its relatively modest surroundings (except for a slight view of Wembley Stadium in the distance), so naturally it will garner some attention. The mandir, however modern, does not seem to lose much of its traditional identity. Hinduism thrives there; thousands are said to pray in the building during the day and more so during holy days.

The BBC has a link to some of the other ways Hindus have had to adapt to a new identity in 21st century, but I am unable to access it on my computer. I suggest taking a look, for it looks informative and will certainly give a much more comprehensive understanding than I can.

3. Hesitatant Adaptation

While the Hindus have voluntarily adapted themselves to modern London, the Sikh community – as understood after a visit to the Gurdwara Sri Guru Singh Sahaba in Southall – has taken some hesitant steps as enforced by British law. For example, one of the five tenets of Sikhism calls for the carrying of a sword for the defense of the weak, justice, and as a representation of God. British law forbids this, so this tenet cannot be fulfilled in 21st century Britain. A second tenet of Sikhism calls for uncut hair, as to symbolize, in part, one’s comfort with how he/she was physically created by God. For many jobs in Britain, one’s hair must be cut and trimmed, and some Sikhs decide to cut their hair accordingly. They lose part of their identifying features as a Sikh when faced with the new identity demanded of them by surrounding British culture. The gentleman who showed us around the gurdwara expressed his desire for all Sikh men to be allowed to carry their ceremonial swords, for, on that day, the two conflicting identities can coexist without having to forego one or the other.

Post-colonial literature points to this hesitant adaptation, but from a different perspective. Buchi Emecheta’s Second Class Citizen traces the difficulties several Nigerians face when trying to willingly adopt the British culture. Racism, prejudice, and misconceptions form a glass ceiling that essentially blocks the immigrants from moving away from their status as a ‘second-class citizen’. The hesitation can be drawn from the communities themselves or from a host identity defined by prejudice; one party cannot take full blame for the contrast between different peoples.

_________________

The construction of identity in the London of 2009 immediately appears like a forever mixed jumble of different practices, rites, and customs fighting for its own place of comfort. I see it as being in a state of disequilibrium, where the role of prejudice and anti-immigration compete with the openness and accommodating nature of some Londoners. Some want to enjoy their own separate community and their own traditions; others are willing to adapt and let their surroundings mold their identity. Neither is wrong, neither will prevent one from having a fulfilling life.

Whew.

I still question my views on this topic, for it is a dense subject to write about. I look forward to the day I come to some brilliant understanding of identity construction and its adaptation/resistance when facing a new identity. Until then, I remain confused, frustrated, and exhausted.

Tags: Brandon

So I’m a bit behind in the posts, and I actually have things I’m supposed to write about rather than just blab on about feet or other nonsense. Qualls wanted us to look at immigrant communities. By wondrous fate, Audrey and I came across a Jewish festival in Regent’s Park. The festival was called Klezmer in the Park, a Jewish music festival. The MC was fantastic and quite hilarious; he even sang a Yiddish rendition of of New York, New York. He brought up an interesting point though: what would an English rendition sound like? With my humble German abilities, I was able to ascertain that he was not speaking in a direct translation, and I wonder how a song(in general) gets changed, either culturally or linguistically, when it comes to a different country. This seems to apply even more prevalent for a song like New York, New York, which is so heavily tied into the culture of a city and its lexical nuances. Back to immigrant communities. It was quite a sight to see, truly. Jews and non-Jews; British and non-British; all dancing and laughing together in Regent’s Park. Such a feet would not have been possible or even dreamable only a short time ago. And yet there it was, in all of its schmutzing glory. What I did find interesting though, was half way through the concert, the MC calls all the male bachelors too silly to avoid his gaze up on stage. While up there, they were bombarded with what I can only imagine were questions a Jewish mother would ask (I have no such mother, so I’m not really sure). What was sad was that no one liked the Jewish men, rather preferring a gardening British non-Jew (evidently Jewish men don’t do well with their hands, I’ll have to ask Barron). But I think this brings up an interesting idea, and one we have touched on before: how do you maintain your cultural identity while continuing to integrate (thus attaining privileges like a festival in the park). How do you maintain a culture that is based around the maternal family line if people are marrying non-Jewish women? While the festival did not speak for the entire British-Jewish community, I would like to believe that it had some microcosmic properties. Next Audrey and I went to Queen Mary’s Garden; it was quite lovely, beautiful flower patches with little roads cutting into the wooded areas, very nice for intellectual conversations and peaceful walks of contemplation, recommended to all.

Now onto what I wanted to talk about: tourists. Bloody tourists. So buddies of mine arrived here a week or so ago, and it’s really startling how loud and boisterous they are. But in saying this, I have to laugh because I cannot be so bold as to say I have transcended the lines of tourist and Londoner–that would be absurd. How snobby does that sound? Quite. I wouldn’t go as far as to say I’m going native, but I think I’ve definitely fallen into a slot of participant observation. But I mean, this is the dream. If I could do ethnographic work for the rest of my life, earning enough to eat and not get trench foot, I would die a happy man. Saddly I realize that isn’t the case, and I’ll just end up behind some desk. So I’ve got to play dress up for as long as I can before the bell tolls, hopefully not making too much of a fool of myself in the process. Keep calm, carry on.

Anyway, cheers

Tags: Andrew R

September 7th, 2009 · 1 Comment

A description under Cradle to Grave by Pharmacopoei states:

“Cradle to Grave explores our approach to health in Britain today and addresses some of the ways that people deal with sickness and try to secure well being.”

It is an understatement when I say that I was surprised to see an exhibit titled “Living and Dying” which is located in Wellcome Trust Gallery in the British Museum. The gallery explores how people around the world deal with “the tough realities of life and death.” The exhibit further explores health challenges shared by many through out the world, and the ways that those individuals might deal with them based on their cultures, beliefs, and areas of residence. Creatively displaying visual representations of photography, quotes, documents, captions, and instillations the exhibit investigated people’s reliance on relationships in order to maintain their well-being. Exploration of people’s relationships with each other, the animal world, ancestors, land and sea for their well being are included.

As I walked down the stairs of the British Museum to the ground floor expecting to see the Aztecs (Mexicana) exhibition featuring tribal sculptures, history, and art instead I was greeted by Cradle to Grave. The central installation consists of two lengths of fabric illustrating the medical stories of a man and a woman. Created by Susie Freeman, who is a textile artist, David Critchley, a video artist, and Dr Liz Lee, a general practitioner, each piece contains over 14,000 drugs representing the estimated average prescribed to every person in Britain in their lifetime, tucked away in ‘pockets’ of knitted nylon filament. This specific piece explored the approach to health in Britain and the personal approach of the piece demonstrates that maintaining well-being is more complex than just treating illness. With 14,000 drugs, the artists included photographs and some treatments that two individuals have gone through. The common treatments for the man and a woman included an injection of vitamin K and immunisations, and both individuals have taken antibiotics and painkillers at various times. Other treatments were more specific such as for asthma and hay fever that the man suffered from when younger and quitting of smoking at seventy due to bad chest infection. The piece showed his death from a stroke at the age of seventy-six, “having taken as many pills in the last ten years of his life as in the first sixty-six.” The woman’s treatments included contraceptive pills and hormone replacement therapy. She was successfully treated for breast cancer. She is still alive at eighty-two although she does suffer from arthritis and diabetes.

Trying to figure out the purpose of the exhibit, I believe the artists are trying to explore the factor of living in the “modern” society and how treating an illness is not the only factor that needs to be taken into account. By representing two individuals, a male and a female, in the British society through photographs with their own captions written down, and objects such as contraceptive pills, a glass of wine, and needles allowed the viewers to relate in some way to the lives these characters have led and how it affected their health.

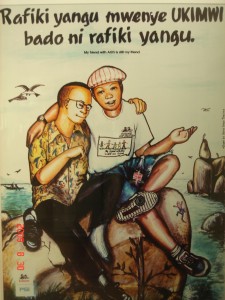

Surrounding the installation, representations of health in countries such as Tanzania, China and India were included. “Facing HIV/AIDS” explored the approaches these communities have to the AIDS epidemic. The stigmas attached to being diagnosed with AIDS in these societies prevent many from seeking treatments; therefore, the need for education programmes, community workshops and poster campaigns which aim to make it easier to discuss and practice safe sex. “Praying for Health” showed how certain communities use prayer and traditional medicine to treat their illness. In contrast to the British healing, it is a very different approach. Focusing more on the person and the higher being rather than the pharmaceutical companies and the business aspect, societies in Tanzania, India and China focus on the being and their needs. Although the treatment of such illnesses such as HIV/AIDS can not be done only through traditional healing, their approach should serve as a guide to western societies where a more humane way to treat patients. There needs to be an infusion between the two worlds.

"My friend with AIDS is still my friend."

Tags: Jeyla · Museums