Entries Tagged as 'Museums'

September 22nd, 2010 · 1 Comment

I have a fondness for paintings, so its only natural that I gravitate towards museums such as the Tate Modern/Britain and the National Gallery. Some of the pieces I’ve seen from these particular museums have been no less than extraordinary. At the TM, I saw works by Monet and Pollock, discovering once again the beauty in blurred lily pads and splattered paint. But as the TM is also a purveyor of contemporary art, I was also able to see recent works that are – at times painfully – trying to subvert and re-express artistic theories. One of the more outstanding contemporary works I saw at the TM was a video installation by Carolee Schneemann. Made in 1964, Meatjoy is a manipulation of the filmic image as a veritable representation of reality into an exercise on sexual discourse that strives to create the notion that “sex” is in our own skin. Half naked men and women wrestle on the floor and arrange themselves in strange positions, as a hardly discernible voiceover of a woman is heard on the soundtrack. Gradually the cuts become more rapid, and people offscreen begin to throw meat and poultry at the “subjects.” Its shocking, even disgusting. But there is no nudity. Some images evoke sexual acts – but they are not sexual in and of themselves. Anyway, I didn’t particularly “like” the film, but it was interesting – and certainly shocking. You can view a short clip of it here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D6AK9TI3-LU

Since the Tate Modern is a global museum and most of its exhibitions are free, there were a lot of people. The escalators and large spaces reminded me of a shopping mall. Its quite a contrast with the Charles Dickens museum, yet both are museums, right?

At the Tate Britain, I was greeted with a smaller crowd. The day that I went to the Tate Modern I was tired, and trying to view the artworks with an open mind is hard to do when there are hordes of people blocking the works from all angles. TB had no such problems. It itself is an impressive museum with an emphasis on British art (duh) but with a respectable collection of international modern art. I even saw a Mondrian painting. I must’ve been sitting in front of it for nearly half an hour. The painting’s greatest virtue is precisely that it is straightforward and pure. In this sense, its somewhat ironic to call it a piece of abstract art. I like it very much, and was impressed at the evocative power of a most primordial form. The painting even looks like a tatami, a seeming reference to the qualities of humility and tranquility that are intrinsic to Japanese culture.

Mondrian: Composition C (No.III) with Red, Yellow and Blue

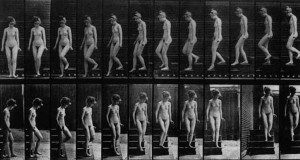

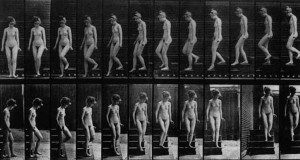

I saw advertisements about an exhibition at the TB exclusively on Eadweard Muybridge, arguably the first person to invent the ontological nature of the cinema. Enough said. The entrance fee was 10 pounds but I didn’t mind. The Muybridge was a fantastic exhibition, much more extensive that I had imagined; there must been at least six rooms. I also appreciated that there was a chronological order to the exhibition, beginning with Muybridge’s photographs from his early years to the prints from the zoetropes in his later. A proper tribute (and indeed, much deserving) to a pioneer who, although recognized in cinema history, unlike the Lumiere Brothers and Edison/Melies/Porter, is seldom talked about among academics and critics. Just looking at his prints, you realize how much of an influence he has had on the history of the medium. So grateful to have caught this. London has been good to me. If anything, one perk of living in the city is, simply, the range and accessibility you have to the arts.

Print of Woman Descending the Stair - Duchamp may have taken inspiration from this...

Mondrian photo courtesy of Tate Britain

Muybridge courtesy of har-avantgarde.blogspot.com

Tags: 2010 Sean · Museums

September 21st, 2010 · 1 Comment

The British Museum. Bang. Zoomph! Woop. Boom! The biggest statues, the coolest marbles, the most languages per stone, a whole bunch of the Parthenon. Beowulf. The museum is like a pirate’s hoard. It is everything awesome that the Brits could find and lug back to their island, displayed in a massive ceiling’d amalgamation of rooms with entirely uncoordinated and impossible to follow numbers that follow no logical pattern. Doesn’t get much better than that. Cleopatra’s body is there! Things that just have no business being there are all just hanging out at the British Museum and it is like it’s no big deal. You wander through the museum, stumbling upon gigantic Egyptian and Greek statues portraying God’s and mythical battles.

This brings me to an interesting point that I am sure has been discussed throughout these blogs ad nauseum. It is this British idea that somehow these priceless objects belong in the British Museum and not, say, back in their respective countries of origin. I’ll refer here to a quote from a plaque in the Greek portion of the museum.

“The Parthenon sculptures in the British Museum were brought to England by Lord Elgin and bought for the Museum in 1816. Elgin’s removal of the sculptures from the ruins of the building has always been a matter of discussion, but one thing is certain- his actions saved them further damage by vandalism, weathering and pollution. It is also thanks to Elgin that generations of visitors have been able to see the sculptures at eye level rather than high up on the building.”

Okay, let’s ignore the last sentence as the Museum is clearly grasping at straws. Obviously, the sculptures could be at eye level in Greece. Instead I’d like to focus on the phrase ‘one thing is certain.’ So that is to say that it isn’t certain that the sculptures should be back in Greece. As if both countries have a legitimate claim to the sculptures and it is a matter of debate, instead of a simple matter of Britain not wanting to give the sculptures back.

The other museum that I found truly blog-worthy is called the Welcomme Collection. It was of interest for a number of reasons. First was simply the content. One of the major exhibits I explored was on medicine, exploring its history. But what really set this museum apart was the way it was presented. The first thing I saw upon walking into the exhibit was a massive plastic model of a person, entirely consumed by bulbous fat. It had no head or features besides legs. And then there was thorough analysis on the side. This wasn’t a museum designed to wow in the way the British Museum did. It was supposed to provoke thought. The exhibit pointed out how humans had evolved in an environment in which we had to walk considerable distances and could not eat very often. And that through technology we eliminated this need to walk while also increasing the availability of calorie-rich foods. And that many developments (such as a remote control, automatic can opener) were designed to remove any sort of exercise from day to day life. But at the same time, humans are inventing products such as stationary bikes to increase artificial exercise. In the next room I came upon three chairs in glass. Two were dentist’s chairs, one from 1900 and the other from before that. The third chair was a torture chair covered in blades and hooks from Ancient China. The plaque on the side did not explain the connection between the three, but it was a shocking exhibit all the same. The final thing of interest about the Welcomme Collection was the clientele. It was mostly young people, teenagers and mid-twenties, and a seemingly alternative culture. Girls with pink Mohawks and black leather jackets, that sort. Another really cool exhibit contained an actual metal chastity belt from centuries ago, which I did not realize existed.

These two museums are particularly interesting when juxtaposed. The British Museum needs no explanation. It’s exhibits are shockingly valuable and famous. The Welcomme Collection provokes thought and puts together interesting and obscure objects.

Tags: 2010 Michael · Museums

September 20th, 2010 · No Comments

The Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington is unique in that instead of focusing on one style or type of art, the exhibits at the Victoria and Albert include diverse forms of decoration. I use the term decoration broadly because the museum is essentially a collection of decorative items and artifacts, including porcelain, tapestry, and other furnishings, mostly from the 16th century onward. Also featured are exhibits on sculpture, but that is for another blog.

The museum bills itself as “the greatest museum of art and design”, and in that respect it fulfills its mission. It would be overly simplistic to say that the Victoria and Albert is simply a collection of the conspicuous consumption of the well heeled before the 20th century, but not completely off the mark. The luxurious possessions which comprised the museum included silver and gold gilded tea sets, large tapestries, and detailed porcelain. For example, there was an exhibit on Chinoiserie, which despite its name, was not specifically a Chinese craft. In fact, Chinoserie was a combination of Japanese, Chinese, and Indian motifs designed and produced in Britain in the mid 18th century.

A section which interested me in particular was the exhibit containing artwork and artifacts involving Johnathan Tyers, an ambitious entreprenuer from the 18th century. Tyers really loved George Friedrich Handel, so much that he commissioned a statue of him for placement in Spring Gardens near Vauxhall.

Taken from (http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O34256/statue-handel/), by Louis Francois Roubiliac.

This statue features the composer playing the lyre of Orpheus, a mythical figure whose music calmed even the most savage beast. Tyers wanted this statue to be placed in the heart of the Gardens, possibly as symbolism of his campaign to convert the gardens from its earlier seediness. Today, I stopped by the gardens, a five minute walk from the Vauxhaul station on the Victoria line, hoping to see the product of Tyers’ toils. But unfortunately the previous gardens had been razed in order to build housing, and when that housing had been demolished the gardens were not restored to their previous glory. The park had clearly reverted to its seedier nature, judging by the sight of a homeless man passed out on a park bench holding a bottle of whisky…

Tags: 2010 Tyler · Museums · Uncategorized

September 20th, 2010 · 1 Comment

On a whim (and because it is the last required museum I haven’t visited), a few of us visited the Sir John Soane museum a couple of Wednesdays ago. Having had no introduction to the museum, we were slightly confused as we arrived at our destination. The man at the gates of this unremarkable-looking English town house first complained that there were eight of us and asked kindly that we “not go around together.” He then had the ladies put their purses into plastic bags to be carried around with them. I had to sign the entire group in on a huge log book and we were off!

We entered the museum but instead of being greeted by an introduction or explanation, we came to room upon room of art and sculpture. The rooms were oddly shaped and almost all lit by giant skylights in the ceilings. As I later learned, John Soane was an architect and he intended his home to serve as an educational space and and inspiration for his students. All of the spaces are top lit so as to allow as much space as possible on the walls for art work. Here’s a picture that gives you an idea of just how packed the museum is. It also shows the high ceilings and circular skylight which was a feature of almost every room.

http://www.creative-freelance.org.uk/reviews/soane.html

I have to say, this was the strangest museum I visited while in London and it was also my favorite. It was unlike any other place we went and it seemed to me quintessentially British. It was inexplicably quirky and reveled in its own strangeness. It was unexpected and unclear and a bit odd.

My impressions of the other museums are as follows:

Victoria and Albert: Interesting but without a cohesive character, unless you count imperialism as a unifying force.

National Portrait Gallery: Anything after 1600 was interesting, anything before was all the same. Admittedly not the most nuanced view but without a bit more context for the portraits I was viewing in the Tudor and Stuart Halls, I was bored by them. I especially enjoyed the Victorian era stuff.

British Museum: Also a product of imperialism but more educational than the Victoria and Albert because I think that the curative work was more focused on teaching us about the places Britain had stolen from. I thought that the podcasts were especially good since they made an effort to contextualize the pieces.

National Gallery: In general, I really enjoyed the artwork. I was disappointed by the Japanese Bridge that they have. Not Monet’s best effort.

Cabinet War Rooms: I enjoyed the War Rooms more for the place than the museum but since the place is so historically important, I found it interesting.

Natural History Museum: The attraction here was more the building than the exhibits themselves which was striking. There are mosaics all over the walls of animals, plants, and fossils. The best exhibit here was also the most mundane. The giant collection of minerals was my favorite part of the museum. It took up an entire hall and held over a hundred cases of any rock or mineral you’d ever want to see.

Tags: 2010 Daniel · Museums · Uncategorized

September 19th, 2010 · No Comments

I’ve said this before but I’ll say it again, in case anyone has missed it: I’m a huge Anglophile. If it’s English, it’s pretty much guaranteed that I’ll love it. Coming to the UK has literally been the fulfillment of a lifelong dream. A huge part of why that is lies in the museums it has to offer.

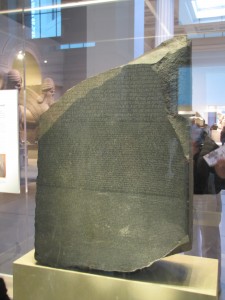

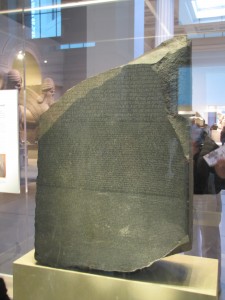

As an English major specialising in 19th Century British Literature and a Medieval & Early Modern Studies Major focusing on Shakespeare and the history of the Tudor dynasty, I’ve been most excited about the museums whose collections have items specifically to do with my areas of interest. These are not always the ones you would think: for example, the British Museum turned out to be somewhat disappointing to me [not to discount its quality or credit at all: I mean, the Rosetta stone was pretty damn cool, as were the Lamassus that I studied in my summer art history course and then got to see in the flesh . . . errr, in the stone?] but the highlight of my visit was the following:

a bust of Shakespeare

and

Engravings of Henry VIII

[all photos, unless otherwise mentioned are personal]

Disappointing, no? I thought so.

On the other hand, I was magnificently surprised by the museums we visited in Greenwich. Having no interest in science whatsoever, I thoroughly enjoyed walking around the Greenwich Observatory, particularly the Octagonal (?) Room:

The Queen’s House too was a lovely surprise. Unfortunately, I left my camera in my bag which I checked when we came in, but imagine this scenario:

The Queen’s House too was a lovely surprise. Unfortunately, I left my camera in my bag which I checked when we came in, but imagine this scenario:

Elizabeth has somewhat unwillingly accompanied her friends into the Queen’s House. No sooner does she enter the first gallery but with whom does she come face to face?

That’s right. My good buddy Henry the Eighth (photo courtesy: http://www.nmm.ac.uk/visit/exhibitions/on-display/the-tudors-at-greenwich-gallery)

That’s right. My good buddy Henry the Eighth (photo courtesy: http://www.nmm.ac.uk/visit/exhibitions/on-display/the-tudors-at-greenwich-gallery)

I enjoyed the Museum of London and the Docklands Museum too but (as I later discovered) because I had picked up some sort of stomach flu, I wasn’t really in the best state of mind to appreciate them fully. I plan to revisit the Museum of London tomorrow – if I’m up to it, for now I’ve got some weird ear, nose and throat infection – and take lots of photos (I had my camera with me when we went as a class, but it decided to die halfway through the Plague presentation). I particularly enjoyed looking at their Vauxhall Gardens presentation and the recreation of Dickens’ London.

I have already expressed my opinions of the National Portrait Gallery elsewhere (http://blogs.dickinson.edu/norwichhumanities/2010/09/national-portrait-gallery-my-two-pence/) but will emphasise again the sheer joy I experienced seeing up close and personal paintings that I’ve looked at in textbooks countless times, particularly this one:

[Elizabeth I coronation portrait- http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw02070/Queen-Elizabeth-I?sText=queen+elizabeth&submitSearchTerm_x=0&submitSearchTerm_y=0&search=ss&OConly=true&firstRun=true&LinkID=mp01452&role=sit&rNo=2)

[Elizabeth I coronation portrait- http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw02070/Queen-Elizabeth-I?sText=queen+elizabeth&submitSearchTerm_x=0&submitSearchTerm_y=0&search=ss&OConly=true&firstRun=true&LinkID=mp01452&role=sit&rNo=2)

I’m uncertain whether or not to call our visits to places like Stonehenge, Wesminster Abbey, the Tower of London, or the Roman Baths (in Bath) “museum visits” but, while I had a tremendous time at all of this sites HUGELY significant to my areas of interest, I couldn’t help but notice that they had been “tourist-ized.” Case in point: at the Tower of London, as you look at the stairs where the bones of the two murdered Princes (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Princes_in_the_tower) were supposedly found, you would hear sound effects on a loop which included such gems as “Mother! Where are you?” and “I thought I was supposed to be king.” This made it feel more like Disneyland and the walkthrough of Sleeping Beauty’s Castle than anything else I’ve seen here so far. Also, they look “interactive displays” perhaps a bit too far:

Yes. An electronic counter which allows visitors to vote on who they think murdered the princes. Besides the sheer cheesiness of this attraction, I’m quite irritated to see that Richard III is still getting the rotten end of the stick. Our dear tour guide John agrees with me on this!

Yes. An electronic counter which allows visitors to vote on who they think murdered the princes. Besides the sheer cheesiness of this attraction, I’m quite irritated to see that Richard III is still getting the rotten end of the stick. Our dear tour guide John agrees with me on this!

Beyond the sometimes-unbearably touristy nature of the Tower’s displays, it was still incredible to stand in the buildings where so much history – history that is of particular interest to me – went down.

I’ve gone to quite a few museums by myself as well. Much as I love our group, sometime it’s nice to go at your own pace or go somewhere that not everyone would want to go. Holly and I experienced this in our visit to the Jane Austen Centre in Bath which, for us, having taken English 399 with Professor Moffat on Austen, didn’t really contain anything we didn’t already know (thanks, Moffat!) but was good fun nonetheless:

On one of our free days, I hit two museums I particularly wanted to see: the Tate Britain (NOT the Tate Modern *shudder*) and the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace.

First of all, I wanted to see the Tate specifically for a portrait of Elizabeth I that I had read was in their collection which, upon visiting, I discovered was either an error on my part or had been taken off display. Nevertheless, I enjoyed wandering around the galleries, particularly when I came across these two pictures, side by side:

On the top, “Ophelia” by Sir John Everett Millais and “The Lady of Shallot” by John William Waterhouse on the bottom.

Both of these paintings are iconic to me and a print of the “Ophelia” adorns the door to my bedroom at home.

As for the Queen’s Gallery, I was thrilled to go for several reasons. First, I wanted to see Buckingham Palace without being a total tourist about it. Second, the current exhibition was entitled Victoria and Albert: Art and Love and I think Victoria and Albert have one of the sweetest love stories in history.

Third and most important, one of the core components of the exhibition was works by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, my ALL TIME FAVOURITE artist, a court portrait painter who painted at least 120 works for Victoria and her family. Again, the special joy here was seeing up close and personal works that I have previously drooled over in textbook or digital format, such as these two :

:

Victoria and Albert, by Winterhalter.

Victoria and Albert, by Winterhalter.

From the Royal Collection (http://www.royalcollection.org.uk/microsites/vanda/MicroSection.asp?themeid=841)

This is, obviously, not a final account of my museum experiences in London and England as a whole. I fully expect to enjoy more in the next few days (hopefully, if I can get myself feeling better) and many repeat visits over the course of the year.

Tags: 2010 Elizabeth · Museums

September 18th, 2010 · 1 Comment

Many blogs and class discussions have centered upon the use (and in some opinions, misuse) of public funds for the museums. No funds have been squandered quite as much as those used for the Sir John Soane museum. Outside the building there is a plaque proudly proclaiming that over 6 million pounds had been raised, primarily via the national lottery, to restore the illustrious home of the architect Sloan, most famous for designing the London Bank (I only found this out because it was one a small plaque inside).

taken from http://blog.londonconnection.com/?p=2799

Honestly, the museum is a huge waste of money. It is like colonial Williamsburg in the sense that it’s a preservation of an older house from a past time, except that it’s completely misrepresentative of early 19th century architecture because it’s too well-designed. Soane’s house is architecturally impressive – many roofs feature intricate designs and the different rooms have many different magnificent qualities. However, there is nothing explaining the various architectural concepts (at least that are clear enough to museum-goers, or just me). There are only few plaques explaining, or even defining, pieces of art or sculptures, which are arranged in hodge-podge and haphazard fashion. Yes, the architecture is impressive. However, it is truly ridiculous to spend 6 million pounds, of public money, to preserve and restore a bit of tiny, though spectacular architecture.

The British Museum, though certainly more expensive, is far more educative than the Soane museum. It not only contains incredible items from world history – it organizes and explains them, giving them far greater meaning then random objects that look cool (or don’t). Because it serves a purpose, it is worth the public money required to fashion such an institution.

Clearly, the Soane Museum best exemplifies the reverse robin-hood syndrome (stealing from the poor, giving to the rich, a common criticism of the publicly-funded museums) because it’s so obscure and not educative that it really serves no purpose to the poor but does cater to rich architecture fanatics and people who already know enough about artifacts and art that they don’t necessarily need plaques explaining them.

There are simply too many better uses for 6 million pounds, the public sponsorship of the Soane museum is, in my opinion, un-sound. What do I make of this then? I think the preservation and sponsorship of the Soane museum highlights England’s obsession with its past, and more specifically, a superficial past. Just as the Imperial war museum champions Britain’s involvement in WW II and skirts over that whole Africa colonialism bit, the Soane museum makes late 19th and early 20th century Britain look classy, as this is a model house from that time. It also simply echoes what we’ve seen before: Britain loves its past, and making it look good.

Tags: 2010 ChristopherB · Museums

September 15th, 2010 · 2 Comments

Unless you have previous knowledge of the museum beforehand, the John Soane Museum will initially confuse you. Expecting to see another massive and imposing building, the Soane Museum is actually just an inconspicuous house located amidst the London city chaos. Without much of an introduction, I wandered inside holding my purse in a clear plastic bag—the reason for which I learned later on—immediately into Sir John Soane’s past. I wandered through the intricate maze of tall and narrow doorways and winding staircases, coming across only a small number of plaques describing Soane and his belongings. I gradually learned he was an English architect, remembered most for his remarkable skill and his design of the Bank of England.

John Soane’s house was incredible. The detail in the architecture was intricate and the colors and designs were nuanced and distinct. Besides the building itself, the objects it housed seemed for the most part entirely out of place. For example, a large open room, extending from a stone basement to a glass roof, exhibits a myriad of ancient Greek stone architectural pieces. Apparently the room is intended for students to wander through feeling as if in Greece while learning about the architecture. Although I appreciated the museum by the end of my personal tour, I could compare it to another museum I visited in Boston and did not enjoy it nearly as much.

Greek Architecture Exhibit, John Soane Museum

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, Massachusetts is similar to the John Soane Museum in that it’s a personal home that displays the past owner’s invaluable possessions. Isabella Gardner was not an architect like Soane, but rather a remarkable art collector, patron of the arts, and philanthropist. Unlike the Soane Museum, the Gardner Museum offered a tour as soon as the visitor entered—something vital when there’s an apparent lack of plaques, brochures, and audio guides. Furthermore, the organization and presentation of the pieces in the Gardner Museum was more effective. Instead of a disorganized jumble, Gardner’s rooms centralized the visitors’ focus on one main piece and designed the rest of the art in the room to reflect and elaborate on the piece’s expression. For example, one room displays a striking, passionate sort of painting, while other sculptures, drawings, plants, and the room’s decoration further emulate the painting’s dark, mysterious emotions.

Painting in Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

In the end, I enjoyed the John Soane Museum as an exploration of one man’s architectural talent and creativity, the rare objects he collected, and his life in 18th and 19th century England. However, it became a challenge when I compared it to another somewhat similar museum that I much preferred over the Soane.

Tags: 2010 Mary · Museums

September 14th, 2010 · 3 Comments

We’ve already talked about the elitism that we’ve seen in museums such as the National Portrait Gallery and the National Gallery, and I’m sure that everyone has at least a passing familiarity with the debate over the Elgin Marbles. (If not, Stephenie wrote a small book about it a few days ago, so just keep scrolling down the page.) I don’t want to beat the imperialism theme over the head too much, so I’ll try to take a different angle here. What has struck me about so many of the museums that we’ve visited has been the vast collections of stuff housed within their walls. Isn’t this the point of musuems? you might ask. Well, yes. But I feel like the size of the collections and the way that they are displayed here just screams “materialism” more loudly than any museum that I’ve visited previously.

Apart from the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum is the best example of this. The array of exhibits in this museum is incredible–everything from fashion to theatre, jewelry, micromosaics, sculpture, medieval art, and every silver dish ever manufactured in the British Empire. Wandering through (the floor plan made absolutely no sense to me, so I just walked around), my eyes started to glaze over because of the sheer number of artifacts displayed. In the silver rooms, for instance, there were cases packed so tightly with pieces that there was not enough room for display cards; interested viewers had to pick up a card that was chained to the outside of the case. And underneath all of these cases, which took up a pretty substantial area, were drawers full of more pieces that didn’t fit in the displays. It was insane. The V&A had some amazing pieces, but the opulence and materialism on display there were astounding.

Although some of the other museums that I visited were much smaller and were actually house museums, I noticed this same glorification of materialism. The Sir John Soane Museum is a wonderfully eccentric home that Soane, a nineteenth-century architect, designed specifically to hold his collection of artifacts and his “cabinet of curiosities.” It’s really neat to walk through and see all of the peices that he has hiding in the nooks and crannies of his home (one room has extendable walls that fold out from the permanent walls. There are currently sketches by J.M.W. Turner that are displayed on these hidden walls). His collection includes several pieces of Greek and Roman statues, wonderful works of art by Hogarth and Canaletto, and even an Egyptian sarcophagus. But again, I got the sense that there were just so many things packed into such a small space. And I had to wonder, like Stephenie, how he came by all of these treasures and why he needed a room full of Roman busts. It seemed as though he had collected all of these things simply because he could. Thankfully he had the foresight to turn his home into a museum so that his collection would be accessible to the public to come and learn from it, but the thought still lingered. The Wallace Collection left a similar feeling, although a large portion of the collection housed there comes from other parts of Europe.

I firmly believe that these huge, opulent collections are only possible because of Britain’s imperial past. They had access to so much of the world, and they had the power and the weapons to take artifacts from all of these places (even if the Elgin Marbles were supposedly sold legally). As the strongest nation of the nineteenth century, Britain was able to amass all of the silver found in the Victoria and Albert Museum, and all of the pieces of sculpture housed in the Soane. The money was there and the artifacts were ripe for the taking, so materialism (and I think fascination with exotic cultures, especially with the Orient) naturally followed. I’m not trying to say that this is right or wrong, and Americans as a whole definitely value the consumer and material wealth. It’s just what has really struck me from the museums that I’ve visited.

Tags: 2010 Holly · Museums

September 11th, 2010 · 2 Comments

While visiting the British Museum several nights ago, I noticed an interesting behavior exhibited by different ethnic groups, depending on the culture focused on in a given room. The exhibits that I was looking at that particular evening (Ancient Greeks and Ancient Asians) were rather diverse, and it was precisely this diversity that alerted me to this phenomenon. While wandering through room after room of Greek artifacts, I noticed that Asian visitors (with only very few exceptions) would pass through these rooms without stopping to actually look at many, if any, of the artifacts. I slowed my pace considerably through the remainder of the exhibit, to observe the most number of people, and sure enough, Asian visitor after Asian visitor passed through the rooms, only occasionally stopping to look at one artifact, or more likely, take a picture, before moving on. Compared to visitors who looked to be of European/American ancestry, the difference is stark. These people generally took their time through the exhibits, stopping to gawk at an exceptional pot or other artifact, and generally going at a more suitable pace for such a wonderful museum (in my opinion).

Intrigued by this, I moved on to the Asian exhibits to see if I could find a similar trend there. Sure enough, I did, but it was almost completely reversed. In this case, the Asian visitors were the ones that were slowing down to look at everything, while the people that were zipping through were almost entirely Caucasian. This is exactly what I expected to find, as my hypothesis prior to entering the Asian room was that people, whether consciously or subconsciously, care more about cultures closest to their own, and are therefore more interested in the history of these cultures. This is why those of Euro-American heritage took their time through the Greek exhibits, but zoomed through the Asian room, while the Asians exhibited the opposite behaviour.

All this may either be evidence for or against the British Museum. This small, unscientific experiment of sorts seems to show that people don’t care about other cultures, at least not as much as their own. It’s very easy to extrapolate this to all sorts of things (for example, various imperialist wars in the Middle East, religious intolerance all over the world, etc.), but I don’t want to make this post too upsetting, so I won’t dwell on sad things, and get back to the Museum. I’d rather think that this phenomenon shows that the Museum has something for everyone. No matter where you’re from, you’ll find a piece of our history at the British Museum. I’d like to think there’s a bit of hope left in the world, so I thoroughly believe that this latter theory more true than its predecessor.

Interestingly, to finish things off, I travelled to the Americas section of the museum to see what kind of demographics it attracted, to compare to my observations in the Greek and Asian sections. I found that no one, no matter who they were or what they looked like, just buzzed through. Everyone was transfixed by the Native American headdresses and canoes, but I found no Americans in the exhibit (It’s surprising how easy we are to pick out, once you live in another culture for a while). This seemed exactly contrary to my other findings, as going off of my findings, you would expect to see a whole gaggle of Americans in the part of the museum dedicated to their history. On closer inspection however, this makes perfect sense. The vast majority of Americans are not of any measurable Native American descent. Instead, we’re predominantly from Europe and Asia, which incidentally are the exhibits in which I found all the “missing” American visitors. This “exception” seems to in fact further prove the rule, as Americans, as part of a “melting pot,” still associate closely with the history of their international forefathers.

Tags: 2010 MatthewM · Museums

September 11th, 2010 · 2 Comments

London’s diverse museums all have an element of British imperialism. The three which best show this are the Wallace Collection, the Sir John Soane Museum, and the British Museum. Yet, each takes a different approach to them: the British Museum is the standard artefact with didactic label, the Soane shows the spoils of an imperialistic age in the wonderful cabinet of curiosities method, and the Wallace Collection arranges its collection as a wonderful combination of the two.

The Rosetta Stone, which has been a centerpiece of the Egyptian repatriation demands.

We’ll start with the British Museum. Perhaps the most controversial collection because of the Elgin Marbles, most of the collection could probably be at the center of a repatriation argument if a government decided to challenge the museum. Instead of noticing that the museum was a shrine to British imperialism, my first thoughts (once I pulled myself away from the medieval galleries) were about the museum’s role in the ongoing battle over countries reclaiming their artefacts. My general beliefs on repatriation are simple: the works belong wherever they are going to get the best care, which, unfortunately for the vast majority of the ancient objects, is not in their countries of origin. For example, there is no way that Egypt can assume responsibility for its antiquities; the ones there are deteriorating alarmingly. While Hawass has done a good deal for Egyptian antiquities, their facilities still are nowhere near those of the British Museum’s facilities. Furthermore, shouldn’t objects that have influenced the whole of history be where the most people have access to them? Surely that is here, in London, not in Cairo?

One of the Elgin Marbles

Unfortunately, that argument is no longer valid for the Elgin Marbles (although, while not as an unpredictable environment as Egypt, Greece does have its problems which could threaten the marbles). Greece has a new acropolis museum that is a perfectly suitable house for the marbles. So, why do I still believe they belong in London? Aside from the whole no-objects-can-leave-England-law and the incredible galleries they are currently housed in, there a couple of reasons. Firstly, their provenance, unlike that of the Italian krater the Met repatriated to Italy, shows them to have been purchased legally versus outrightly stolen. We may not agree with the way they were handled in the 19th century, but because we have a different understanding of the proper way artworks should be sold/purchased does not mean we can go back and make amends with everything. The world’s great museums would be emptied. Secondly, where they are now, they are more accessible. If Greece didn’t have almost as many as the BM, I’m sure everyone would feel differently about the issue. (Well, except for Greece, which would still demand them all, even in the BM only had one.) Because repatriation has become such an important issue, I do believe that even if English law did not forbid it, the marbles would never go back to Greece because once the BM accepts Greece’s arguments, the watershed for repatriation will be open and museums will be scrambling to quadruple check their works’ provenances, possibly wasting valuable resources.

It was only after my second visit to the British Museum that I wondered about some of the works’ provenances. However, from the moment I stepped into the Sir John Soane, all I wanted to do was demand to see some of the provenances of various works, as well as pick up the objects to examine them and the way that they were removed from their original locations. I think part of the reason that it took a second visit to the BM to question it was as one of the leading museums in the world, it has more authority as the stellar, but smaller, Soane. The traditional layout of the BM commands respect, whereas the Soane is easy to mistake for a pile of junk haphazardly arranged. Except, it is the exact opposite: the Soane has incredible pieces. (I could have died of joy looking at the random Gothic bits.) Because of the arrangement- a life size cabinet of curiosities- it is easy to forget that all of the works can point to the achievements of Soane and his time, noticeably imperialism. When walking through, one’s mind is trying to take in everything and is not assisted by didactics, the larger picture is sometimes lost, unlike at the BM, where the layout and didactics remind you almost constantly that while the museum is “British”, the majority of the collection is not. Furthermore, the Soane’s arrangement allows one to feel closer to the objects. Indeed, it is easy to get away with a close examination of the work on the wall and touching them. In the BM, the viewer is often annoyingly separated from the work by class or a rope barrier.

If the BM is arguably the most controversial museum because of its collection, then the Soane is the most overlooked for controversy. Lots of the works were supposedly removed from crumbling sites. Were the sites crumbling before or after the works were removed? Did the dealers have explicit permission? These questions are largely overlooked; in fact, lots of information is overlooked, which adds to the feel of a cabinet of curiosity.

The Wallace Collection

The Wallace Collection is like the Soane in that it started as one cohesive collection and has grown, as well as that it shows the way the works were staged by their original collector. However, unlike at the Soane, the Wallace Collection does an amazing job of showing lots of works in a way that is not as overwhelming. The collection is mostly housed in period rooms, which add to the atmosphere of the museum, greatly enhancing the works. Instead of wondering about whether the objects should be repatriated, the collection sets up the works in such a way that the viewer is not distracted by theoretical questions on museum practices. (Unless said viewer gets bored of Rococo and armour.) Furthermore, the collection focuses on European art, which focuses it a bit more than the other two museums. If anyone is interested in armour, the Wallace’s collection is superb and world-renowned. Instead of wandering around the museum pointing to works I wanted to examine for causes to repatriate, I wandered the Wallace wondering why certain works were hung together and why anyone would want rooms upon rooms of Rococo art, much less why I was wondering around them when there were three outstanding armouries downstairs that were calling me.

Yet, part of me wonders if Britain didn’t have it’s imperial past, would I be able to see this quality of art and artefacts. If I were able to, would I wonder about the provenance and history of each work as much?

Tags: 2010 Stephenie · Museums

[Elizabeth I coronation portrait- http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw02070/Queen-Elizabeth-I?sText=queen+elizabeth&submitSearchTerm_x=0&submitSearchTerm_y=0&search=ss&OConly=true&firstRun=true&LinkID=mp01452&role=sit&rNo=2)

[Elizabeth I coronation portrait- http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw02070/Queen-Elizabeth-I?sText=queen+elizabeth&submitSearchTerm_x=0&submitSearchTerm_y=0&search=ss&OConly=true&firstRun=true&LinkID=mp01452&role=sit&rNo=2)

:

: Victoria and Albert, by Winterhalter.

Victoria and Albert, by Winterhalter.