Entries Tagged as 'Museums'

September 11th, 2010 · 1 Comment

Throughout our time here so far, I’ve been to museums that I’ve loved and loathed. Regardless of how I felt about the collections, each museum seemed to say something about England, as well as demonstrate amazing educational programs. (I’ve decided to tackle the issue of museums in two separate blogs. I’m not going to deal with repatriation and provenance, both issues have been on my mind a good deal at a couple of the museums, most noticeably the British Museum and the Sir John Soane museum, in a second blog. This one will be more general and focus a bit on educational programming within the galleries.)

Firstly, thinking back to over two weeks ago, the Greenwich Observatory was an interesting museum. It wasn’t one of my favourites, partly because of the collection, most of which I did not really care for. However, the excellent interactive bits throughout the exhibits were engaging. It did a good job explaining the importance of Greenwich time and it’s relationship to the development of shipping. (I probably know more about longitude now than I ever needed to know.) Unlike the other museums I’ve visited, the achievements it highlighted, were an integral part of the build-up to imperialism vs the spoils of imperialism.

Prime Meridian

The Tate Modern would be my next least favourite. I like some modern art, but it is not normally my first choice to spend an afternoon admiring. (Unless it is a Kandinsky show.) Throughout the Tate, I felt that some of the space had been wasted, especially on the floor where the membership room was located. The main galleries were nice, but offered very little in terms of supplemental didactic materials that could further engage the viewer- all of that was outside of the gallery. While the interactive bits were very interesting, they could easily distract from the art itself. (The seemingly endless reel of video shorts seemed to confirm this.) Yet, I admired the activities for the younger children which engaged them and put the art on their level. By separating the modern art from its other collections, the Tate seems to promote its standing: it is worth more than a gallery add-on in the main building.

The Tate Modern

The Guildhall Art Gallery, by comparison, offered very little interactive displays. By the time I had visited here, I was so use to in-depth descriptions, a wide audience, crowded galleries, and fun didactics, that the seemingly empty gallery caught me off guard. It was nice to see the Roman Amphitheater; the room’s set-up was incredible with recreations of the gladiators. However, the gallery’s art collection was lacking. It mostly seemed to be lesser works of second-tier artists or smaller copies of major artworks created later in an artist’s career. I believe that the gallery was trying to show the positives of British art in the last 200 years, but the gallery failed in this mission because it failed to hold one’s attention for long. Furthermore, the special exhibitions were too text panel heavy. (Balance seems to haunt this gallery.) The panels were informative, but when 3/4 of a panel is devoted to reproducing a picture which is hanging next to the panel, there is a problem. The viewer is drawn to the reproduction, not the actual artwork, defeating the point of the gallery.

The National Gallery is one of my favourites that I have visited, partly because of the Wilton Diptych and partly because there is one spot where my favourite Holbein and a Vermeer are both in one’s line of sight. The collection is outstanding and the works seem to represent the majority of art history. Well, my favourite bits at the very least. While there are not as many interactive activities, the didactics are engaging and there are educational options available. Instead of only seeming to be the spoils of imperialism, the collection has a truly British feel, partly because so many of the works are ones that directly relate to English history rather than the history of far off places. Furthermore, it’s easily accessible and not hidden like the NPG; it’s prominent position on Trafalgar Square also helps with accessibility.

The Wilton Diptych

(For more information: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/english-or-french-the-wilton-diptych)

The Victoria & Albert would be tied for my second favourite museum thus far with the National Gallery and the British Museum (which I’ll discuss in my other museum post). I spent almost 2.5 hours in the new Medieval and Renaissance Galleries, which were not only gorgeous, but held some incredible pieces. (Can I please just have one grotesque figure?! Just one…) Several people have noted that the sheer amount of stuff in the museum is overwhelming. Outside of the M&R Galleries, I would agree with this. Here, the museum seemed to be addressing this issue, trying to open up the galleries and spread out some of the pieces. Furthermore, the excellent listening stations found throughout the galleries were a perfect mix of in-depth and cursory information, allowing the viewer to pick and choose the information they heard based on their interests. (Highlight: listening to Gregorian chants while viewing the different altarpieces, all of which were stunning.) The V&A proudly displayed artworks which combined to tell the story of the world through art. Unlike the British Museum, it did not claim to be a solely British institution, which I think in some ways helped make the museum a more open place. Furthermore, because it is an artistic school as well, it’s collections are all educational, adding to a different responsibility for its didactics and what is should be collecting. It filled gaps through its amazing replicas gallery, which included some of the most famous works ever created.

Misericord, Victoria & Albert

When taken together, the museums not only provide one of the most stellar examples of museum education in practice, but also serve to tell the triumphs of the British Empire and to highlight the triumphs of the larger artistic international tradition. If London is a city of the world, then its museums reflect this.

Tags: 2010 Stephenie · Museums

September 11th, 2010 · 3 Comments

As you probably all already know, I come from a really big family. For my time in the UK, that means SOUVENIRS. By the truckload. Seriously, I won’t be surprised if I have to check an extra suitcase just full of trinkets to bring home to my parents, siblings and cousins. Pretty much everywhere we go, I look through the gift shops to see if anything grabs my attention. So far, I’ve collected novelty mugs, decks of cards, pens, pencil sharpeners, magnets, Christmas ornaments…and I’m not even halfway done.

So after all this time spent in the gift shops, I’m starting to notice a few patterns. It goes without saying that the kitschier the gift shop, the more touristy the location. I mean, I doubt that many actual Londoners (outside of elementary school students on field trips) visit the Tower of London, just like I doubt many Londoners would want the beaded Union Jack change purse I bought my sister in the gift shop there. How many people who actually live in Stratford want overpriced chocolate with Shakespeare’s face on it when they could just go to Tesco? How many people who actually live in Bath want Christmas ornaments of Roman soldiers, or leather bookmarks with a gold embossed likeness of the baths on them? I think by this point we can all stop a tourist trap – or at least a tourist destination – a kilometer away.

On the other hand, we’ve seen some gift shops that don’t seem to cater directly, or exclusively, to out-of-towners. Take the V&A, for example. It’s full of fun jewelry and stationary and other knick-knacks that don’t scream “I WENT TO THE V&A.” A lot of the gifts focus on the art displayed in the museum, rather than reminding us of the museum itself. The National Gallery is the same way – greeting cards and tea pots with prints on them, coffee table books centered around a particular artist – Monet, for example – rather than the content of the collections. Its gifts, in short, aren’t just advertisements. The British Museum was the most interesting of all – it has sections for many of the nations the museum represents. I’m serious. You can buy sequined notebooks and pens from “India.” You can buy colored pencils in sarcophagus-shaped tins from “Egypt.” On the one hand, these items aren’t really “souvenirs” – nothing about them suggests that you went to England and all your little brother got was this lousy [fill in the blank]. This suggests that the museum expects to get a lot of traffic from Brits, if not Londoners themselves. (Could there be a class issue here, as well?)

As a sidenote, is it just me or is it a little disturbing that the British Museum gets to profit off tacky trinkets they designed after the priceless artifacts they’ve copped from the same countries they’re now selling these trinkets in the name of? Whatever. I guess what I mean is , it’s interesting to see which of London’s historical sites are at least as much for British citizens as they are for tourists. By my estimation, I’d say the National Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery, the V&A, the Tate and the British Museum expect to cater to many Brits. Appropriate, since they’re all subsidized. And since they have the most valuable and, in my opinion, the best collections of any of the sites we’ve been to, I guess this is just more evidence that Brits have good taste.

Tags: 2010 MaryKate · Museums

September 9th, 2010 · 4 Comments

In addition to its collection of British royal armour, the White Tower Museum at the Tower of London had an incredible collection of armour and weaponry from countries including China, Japan, Germany, and Russia. Of particular interest to me was a helmet and a dagger, both of Indian origin. The dagger, also known as a Katar, is decorated with a scene which includes the Hindu deities Krishna (playing the flute) and Vishnu. Both serve a cerimonial purpose and were not meant for use in battle.

What suprised me when reading the plaque next to these items was the was the lack of detail in describing how these items were obtained. The plaque in question simply stated that the helmet and dagger were given as a diplomatic gift to the East India Company, who then donated it to be exhibited in British museums such as the White Tower. Without explaining the influence of the East India Company in colonial India, little context is given to the aquisition of these “diplomatic gifts”.

First, the East India Company was known to use violence to achieve its trade monopoly on the Indian Subcontinent. In many cases, the company hired local mercenaries, also known as Sepoys (although I dont remember if the term was used in the description of the Rebellion of 1857 in White Teeth). This divide and conquer strategy, pitting the local population against each other, allowed the company to profit extensively through exploitative trade and working conditions as well as consolidate power throughout the subcontinent.

Also, many of the so called treaties that were formed between the East India Company and the local ruling classes were later violated by the company, so to term any gifts from the local nobility as “diplomatic” is to completely whitewash the lack of concern that the company held for these agreements. These treaties were often formed under duress or fear of violence, so the local ruling class likely had very good reason to give the invaders valuable gifts that they would normally retain for posterity.

I asked a curator in the museum if he had more specific information on how these two treasures were obtained by the East India Company, but unfortunately he was unable to tell me anything about the object besides it being on loan from another museum in the UK. He also interestingly stated that the items were donated to a museum because the company had no use for them.

Do you think that describing these items as diplomatic gifts is appropriate?

Tags: 2010 Tyler · Museums · readings

September 9th, 2010 · 2 Comments

The British Museum is probably the best place in the world to get a historical narrative of the collective human race. This is probably because at the end of the 18th century when the museum was founded, the British Empire was at its peak and the government wanted to show its citizens items from the mysterious and exotic reaches of the empire. So throughout the century items from all over the world were shipped to London.

We can still see all of those items there today, and I have already spent many many hours exploring the museum’s diverse and extensive collection. I really enjoy the opportunity to listen to the podcasts (the history of the world in 100 items) on my journey through the museum. It was while listening to the podcast today about the Chinese Han Lacquer Cup that I began to notice something. Although the podcast references the items role in its specific country of origin, its primary goal is to show the listener where the piece fits in the history of the human race, as most items represent an idea or new technological skill.

This is a very globalizing force because all of the objects, whether Greek, Chinese, or Roman, are discussed in a way that illustrates them as items of human creation rather then objects of any specific empire or nation. In fact the museum tends to make the pieces culturally neutral as well by making most rooms look exactly the same. Each room has a glass case on each wall with perpendicular glass cases jutting out into the center of the room. In the middle occasionally there will be a larger item of more significance. As an avid attendee of American museums, I am spoiled by the Metropolitan Museum’s ability to change the layout and design of each room depending on what culture is on display.

Perhaps this monotonous layout is designed to do what the podcast also attempts to do, make it one universal history unified in the museum by carbon copied rooms. This then gets to the debate brought up all over the world of whether or not those items even belong in the British Museum, but that is entirely too much to discuss in one blog.

Tags: 2010 MatthewG · Museums

Taken from dickensmuseum.com

If you’re a fan of Dickens you must make your way to 48 Doughty Street (it’s only a fifteen minute walk from Arran), and visit the Dickens House Museum. And if you’re not, well, you still should if only because it isn’t everyday that you can see the working milieu of one of the greatest fiction writers ever to live. Evidently, the museum isn’t as large as the other ones we’ve been too, but what it lacks in breadth it makes up for by its dedication in preserving many of Dickens’ possessions. If, however, you are looking for a contextual study of Dickens and London politics, you may be disappointed. Rather, those interested in the author’s biography would seem to be the ideal viewers. Indeed, one of the more interesting aspects of the house is the presentation of the women in Dickens’ life, and how they affected his work. For instance, an entire room is devoted to his sister-in-law, Mary Hograth, who died prematurely at the age of seventeen in Dickens’ own arms. Apparently, Dickens had a bit of a crush. One of the notes describes how smitten Dickens was with Hograth (her death had impeded the serial publication of the next chapter in Pickwick Papers), how he had viewed her as his little sister, even calling her – very mawkishly – as the manifestation of an angel. If I recall correctly, other information cards described Dickens long love affair with a young woman. This may all sound conspiratorial. I thought so too. But a quick Google search will confirm the points. Besides, the museum is run by the Dickens fellowship, the largest organization committed to commemorating all things Dickens. There are even some attempts at amateur criticism, with some notes trying to draw parallels between Dickens’ life and his art, juxtaposing lines from the novels against real incidents. For an “institution” that is meant to honor the author, I found it commendable that the inclusion of such amorous, if you will, details were given proper exposure. It was clear to me that the museum wasn’t interested in providing another grandiloquent version of Dickens’ life. More precisely, there was an aim to be more objective and encompassing, and less inhibitive. I am no Dickens expert so there very well may be much scholarship on this already, but I thought it would be an interesting paper topic to reinterpret Dickens’ novels through a history of his sexuality (Paging Professor Moffat!).

Again, the museum is small in scope and clearly lacks the sumptuous settings of others. But if you find museums such as the Victoria and Albert exhausting, the Dickens House may prove to be a refreshing alternative.

Tags: 2010 Sean · Museums

As a political period in the history of British royalty, the British Regency began when King George III was declared unfit to rule in 1811. During the Regency, King George III’s son held the powers of the King, until he was crowned King George IV after his father’s death in 1819. However, art historians oft define the Regency as beginning in 1789, the start of the French Revolution. Throughout the French Revolution, ideals such as nationalism were promoted through paintings and portraits which glorified famous battles and military leaders such as Napoleon Bonaparte. But how did these aesthetic changes affect portraiture in non-Revolutionary Britain?

Picture courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw03241/Thomas-Hope?LinkID=…, by Sir William Beechey

This portrait of Thomas Hope was painted by Sir William Beechey and first exhibited in 1799. Thomas Hope was born in 1769 into a Dutch merchant family, and his personal interests show a marked interest in foriegn culture. He travelled extensively throughout the Near East, including what is now Turkey and Syria.

In this portrait, Hope is dressed in clothing that was customarily worn throughout the Ottoman lands, but not in Western Europe. Interestingly, it is noted in the exhibit that Hope coined the phrase “interior design”, and this portrait was commissioned in order to be placed into his home, which also served as an exhibition for his design ideas.

This portrait serves to exalt the oriental aesthetics that Hope used in his own designs, and to portray a cosmopolitanism that was in fashion during this time of expanding world commerce. It is also important to note that as European colonial powers such as Britain and France increased their influence in lands such as Egypt during the Napoleonic era, interest in exotic products that were produced by these cultures also increased.

Tags: 2010 Tyler · Museums

September 8th, 2010 · 1 Comment

Today, I visited The Sir John Soane Museum, which I must say is not your typical museum. It is located in the building that its architect namesake built especially to house his collection of priceless artifacts in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. Like many museums of the time, the owner’s philosophy for museum organization was basically to just cover the entire building in artifacts. The current museum staff has put a lot of effort into maintaining this philosophy, for better or for worse. Unfortunately, no picture can do the museum justice (which sounds better than just saying that the museum doesn’t allow pictures, which is an assumption that I made, not a fact), so you’ll have to go to the museum yourself to realize exactly how overwhelming it is. Every surface is covered in pieces from everywhere from Ancient Egypt and Greece through the Middle Ages. While this method of displaying art has historical value and is a good way of showing a lot in a small space, I’m not sure I’m a fan of it. Not only is it overwhelming, but it doesn’t do the art justice. All over the place are pieces that would normally be by themselves in a case, like the sarcophagus of Seti I, one of Egypt’s early princes. Instead, they’re all jumbled together, which makes it hard to appreciate them. Also, the way in which some pieces were displayed, especially ancient clay pots placed around the mezzanine between the ground floor and the basement, was clearly very unsafe, if preservation of the art is the goal, which it should be. It would be far too easy to destroy a priceless piece of pottery just by accidentally bumping it on your way past. A painting displayed in direct sunlight also comes to mind as a piece displayed in a unsustainable way. It’s interesting to compare the Soane Museum to other museums that we have visited in London, because most museums take very good care of their art, locking it in temperature-controlled glass cases. One of the few things I like about the Soane’s method is that it’s very easy to relate to the art because you can actually feel it if you want to (since there were no signs saying “Do Not Touch”, though that does not mean that I touched anything, because I understand basic preservation techniques) and it’s right in front of you. Either way, I believe the museum was a very good learning experience, and would recommend it to anyone visiting London.

Tags: 2010 MatthewM · Museums

September 7th, 2010 · 4 Comments

While visiting the museums of London over the last two weeks, I’ve noticed that several of them seem to have only been opened for the purpose of showing off how powerful the British Empire was at its height. This is especially pronounced at the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. While I’m normally not much of a fan of imperialism, or any act of a bigger country dominating a little country, both of these museums have made me start to appreciate British Imperialism much more.

Let’s start with the British Museum. The British Museum may be seen by outsiders as a huge building filled with artifacts that the British stole from all the places they conquered. This isn’t completely true… Some of the pieces were stolen from countries that were never part of the Empire. In fact, there have been high-profile claims on British Museum artifacts from countries on four of the seven continents. The most notable claims are on the Rosetta Stone (which is their coolest artifact, in my opinion) and the Elgin Marbles, which are parts of the Athenian Parthenon. Luckily for London tourists, in 1963, Parliament passed the British Museum Act of 1963, which prevents any object from leaving the museum’s collection once it has entered it. This allows the British Museum to continue to be a concentration point for really cool artifacts, like original Roman letters, the Rosetta Stone, and parts of many ancient structures. On the flip side, I understand why countries would want their artifacts back. It’s their history, and it makes sense that they want it back. However, from my point of view as a visitor to London, I’d much rather walk 2 minutes from the Arran House to see the Rosetta Stone than have to fly the whole way to Egypt.

From what I’ve seen of it, The Victoria and Albert Museum isn’t quite so overwhelmingly imperialistic, though that might be because I wasn’t able to visit the international sections of it (yet). From what I have seen, a lot of the materials was donated or otherwise given to the museum, as opposed to the British Museum’s acquisition by domination feel. All the same, the V&A made me feel like it was trying to show me how awesome England was in its heyday, and was probably first started to glorify the power of the Empire. Now, it serves as the world’s largest decorative arts and design museum, covering varieties of art like glass, ceramics, metalwork, stained glass, theatre and performance, along with sections on Victorian English home furnishings and more “traditional” pieces like paintings and sculpture from ancient through modern times. Even now, it is a very daunting place (I only got lost two or three times), but at the same time, it is a very fun place. Where else in the world can you see an Apple computer and a 1980’s Save the Miners mug on display in the same museum as priceless jewelry from centuries ago and costumes from the musical version of The Lion King?

Tags: 2010 MatthewM · Museums

September 6th, 2010 · 3 Comments

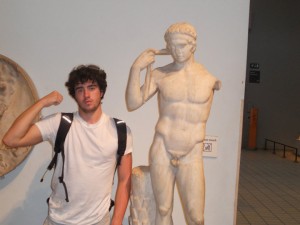

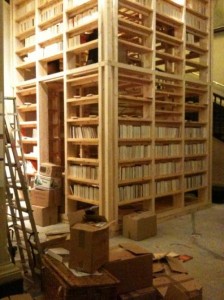

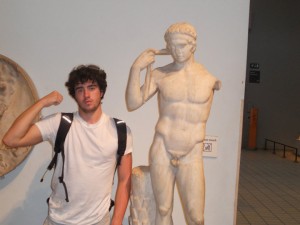

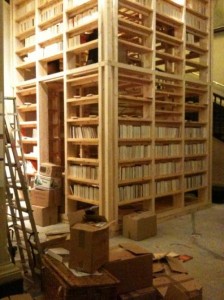

When going to the Victoria and Albert Museum the first rule is: do not get a map. It is completely useless. It will only make you more confused (if that is at all possible). The Victoria and Albert is like no other museum I’ve ever been to. Instead of the sparse but well cataloged rooms of the British Museum or the abstract instillation art of the Tate Modern, there is just “stuff.” It feels as if one has stumbled into a very eccentric, very wealthy old man’s closet. There is a vague sense of organization, but the curator has not stuck to a strict order. Instead one is assaulted with a variety of priceless artifacts. To top the disorganization of the rooms is the disorganization of the building itself. The rooms flow into one another like a maze. From the moment I walked in I should have known that it was going to be a completely new experience — immediately outside of the tube station there was an exhibit filled with treasures that would have been centerpiece at many smaller museums. I then continued into the fashion exhibit which was filled with a barrage priceless vintage clothing from across the world. From there we went through the sculpture hall to the one piece that I felt summed up the museum as a whole: a book tower. It was a multi-storied wooden structure just filled with a random assortment of books — everything from romance novels to Chaucer to Russian literature. This disorganization and jumble of priceless and random books should have been an indicator that my day was about to get a lot more impressive.

(courtesy of http://www.vam.ac.uk/things-to-do/blogs/11-architects-build-small-spaces)

(courtesy of http://www.vam.ac.uk/things-to-do/blogs/11-architects-build-small-spaces)

The madness of the Victoria and Albert reached its pinnacle in the Medieval and Renaissance section where upon a cursory browsing I stumbled upon a little journal tucked away behind a wall. This journal was not accompanied with any great display or paired with a painting or some other artifact — it stood on its own. This unassuming little book turned out to be a Da Vinci journal. If it had not been for the presence of a gold plaque indicating that it was something special I would not have even read the explanation. However, it was a room full or gold plaques and priceless artifacts and it was a completely fluke that I stopped and looked. From this point on, I just gave up. I was too incredulous to take the Victoria and Albert seriously. In a world where small local museums are starving for artifacts the Victoria and Albert have so many that they just cannot display them to their full potential. I personally wish that the Victoria and Albert would loan out items to eliminate the clutter and share their wealth. This would make the museum less overwhelming and it would allow more people to view more fascinating treasures.

Tags: 2010 Amy · Museums · Uncategorized

When I visited the National Portrait Gallery the other day, I was pretty bored by the Tudor and Stuart portraits. If only we had portraiture of the ‘true lives’ of those figures rather than just stuffy, formulaic paintings. However, I was much happier when I finally got to the meat of the museum and started to see some literary and philosophical heavy hitters pictured. When we went on our Bloomsbury walk, I enjoyed hearing about the lives of the many interesting people who’ve lived here. It was neat to go one layer deeper at the Portrait gallery and see some portrayals of the society we’d heard about. In particular, I found a painting by Augustus John of Lady Ottoline Morrell. (Exhibit A):

#mce_temp_url#

The caption informed me that Lady Morrell was a socialite who entertained the likes of Aldous Huxley at her home in Bloomsbury. I was initially attracted to the photograph for its unattractiveness. Ms. Morrell seems to have some serious defect of the mouth in this portrait. A search of the NPG’s collections reveals two facts about Ms. Morrell’s likeness. First, the portrait I saw hanging in the gallery was accepted in lieu of taxes by Her Majesty’s government in 1990 and subsequently given to the gallery. Second, the Augustus John portrait is one of several hundred portraits of Lady Morrell which the museum holds (I got to page 6 of 60 of portraits before I stopped looking). None of the other portraits seemed to show the same deformed mouth as this one. And this, the one portrait with the markedly unattractive feature was the painting chosen for inclusion in the gallery. Curious.

I next came to a portrait of Aldous Huxley which showed him as a young man. Beneath the painting was a caption which informed me that Huxley had written the collection of essays, The Doors of Perception, while on mescaline. Fun fact there. Here’s the portrait of Huxley…. (Exhibit B):

#mce_temp_url#

All of this made me wish I could have been hanging around Bloomsbury during the days of Woolf, Huxley, and Morrell. Of course, they probably wouldn’t have let me in….

Tags: 2010 Daniel · Museums