September 21st, 2010 · No Comments

England’s religious identities are many. The influx of Muslims, Sikhs, and Hindus over the past century has turned the nation into a melting pot of both cultures and faiths. With the complexity of the social makeup of the city, it’s hard to pin down a “religious identity” for the whole of London. That being said, I think that one place of worship certainly has to be regarded as the national symbol for faith and strength- St. Paul’s Cathedral. While the religious denotations of the church are ever present, I don’t think the fact that it is a place of Christian worship is necessarily what gives it its majesty or its importance to Londoners across the metropolis. It is, above all, a symbol of a culture; strong and resilient, huge and complex, beautiful in its intricacies. There are two major times in London’s history during which the citizens of the city- Christian or not- have needed St. Paul’s.

Rebuilding after the Great Fire-

The Great Fire of 1666 ravaged the city whole. It gutted the mostly wood-lined streets and left a smoldering heap in its wake. The old St. Paul’s Cathedral (on whose ashes Wren’s St. Paul’s is built) was utterly destroyed. Wren sought to bring a new, majestic design to the table- he wanted a Renaissance-style dome to crown his masterwork and to be visible for miles around. While the design was initially scoffed at, his beautiful dome was completed and stood as the tallest structure in the city for three centuries. The cathedral is a symbol of Christianity, to be sure. But it is also, almost more importantly, a symbol of London’s rebirth from the depths of the catastrophe of 1666. The visible and towering symbol of Britain’s strength most certainly gave Londoners hope that their city was not only being restored, but taken to new heights.

The Blitz-

In terms of pure physical damage to the city, the only event that comes close to the devastation of the Great Fire is the Blitz. Nazi bombers annihilated much of the city in waves of attacks, night after night. Much of the history of the city was lost in the bombing raids, but the most important symbol of London’s strength miraculously remained. The iconic photograph of St. Paul’s, seemingly engulfed in flames but standing tall and true, is the embodiment of the church’s significance. Wren built the cathedral from the ashes of one fire with the intention that it would be a symbol of the strength of God and the strength of the city. The fact that the symbol itself resisted a second fire, an even greater test of resolve, is testament to its stature as the guiding light of London’s people. Christian or Muslim or Sikh, it’s impossible for Londoners not to stand in reverence (or, at least, in awe) of this building.

http://www.johndclare.net/wwii6b.htm

Tags: 2010 Patrick

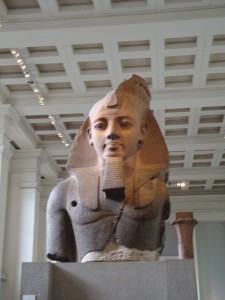

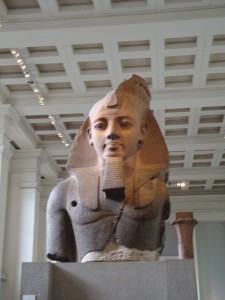

When discussing the sphinx of Taharqo at the British Museum, the Kushite king of Egypt, the narrator of A History of the World states that “it makes sense to keep using a language of control that everybody is accustom to accept.” This is in reference to the fact that during their reign in Egypt, the Kushites adopted Egyptian customs to appease the people they were controlling. In response, the Egyptians likewise attempted to absorb the Kushites into their own culture, “blandly calling the reign of the Kushite kings the 25th dynasty, thus quietly incorporating them into an unbroken story of an eternal Egypt.” It’s clear to me from this that naming something, the smallest thing – the ethnicity of an emperor, the description of a statue, the favorite food of a people – is away to secure power. Speakers in history will always maintain their superiority.

These strategic cultural “inclusions” smack of what Tarquin Hall points out of imperialism in Salaam: Brick Lane when Aktar states in frustration “you people are quite capable of making absolutely anything English if you choose to do so” (247). Imperial nations absorb parts of a culture they conquer to please the people, water it down, and spit it back out as only barely recognizable, a part of the empire. This is what I sense other people worried of Afro-Carribbean culture in their analyses of the Nottinghill Carnival, and possibly with good reason. What was once a celebration of culture could easily become a sort of spectacle for dominant groups. Maybe people come to the carnival to party rather than celebrate a culture. Maybe they come looking for something “authentic” and tokenize Afro-Caribbean culture rather than really respecting it.

I’ve been seeing this pattern all over England. There are curry shops everywhere. I’ve had more opportunity to buy it that than fish and chips. I keep seeing women on the Tube in head coverings, but otherwise wearing Western clothing, and I have to wonder if England and it’s vestiges of imperial culture are somehow swallowing other cultures as well. I see mixed race couples, and wonder what they call themselves since hybrid identities like Asian-American don’t really seem to exist in Britain the way they do back home.

I have always been taught that assimilation is a tool for silencing so marginalized groups can’t write their own history. In the United States, when someone tells you to speak English, straighten your hair, and embrace the American Dream, it really means your people are ugly and unimportant; pretend to belong and maybe we will tolerate you. But at the same time, the absorption of different cultures in England really could be a compromise. I haven’t heard any racial slurs yet. The fact that there is so much diversity and interracial mingling without conflict suggests that people don’t feel marginalized. Rather being coerced or having their customs forcibly erased, maybe new immigrant English consciously choose to adopt some dominant customs as a way to gain acceptance Maybe assimilation in this case is really the kind of cultural sharing that a society needs to operate peacefully. But my American instincts are still tell me to run before I start saying sorry every 5 seconds and can’t talk about money.

Tags: 2010 Jesse · Uncategorized

September 15th, 2009 · 1 Comment

Today I visited the British Museum. Yes, I know, I am probably the LAST person to go there. But to be honest, I was really putting it off. Now that may seem strange to you, since if you’ve been keeping up with my blog, you know I ADORE museums. Yet, for some reason the idea of museum that I could spend my entire life trying to see the entire collection of, just didn’t get me going. I was told it was a history museum, told it was vast, told it was cool. But still. I’m not a history museum fan and I guess the past month has really museumed me out. With all that being said, I LOVED it.

Egypt Wing of museum

And I loved it for several different reasons. The first and less detailed reason was what I faced when I first ventured into a gallery. It was the Egypt wing. I am not a fan. I don’t dislike all the mummy cases and pharaoh busts, they just aren’t really my thing. But back in Brooklyn, at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the museum that I have been going to since my stroller days, the first place where I took an art class, and where I spent my summer interning, there is a HUGE Egypt wing. And suddenly, there I was, middle of the British Museum Egypt wing, in London, in England, in a FOREIGN COUNTRY, and home, all at once. I didn’t stay in the wing long, but the small boost of Brooklyn love I got from the wing was just what I needed before we embark on our new adventure to Norwich.

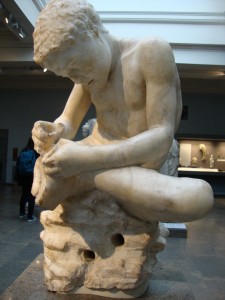

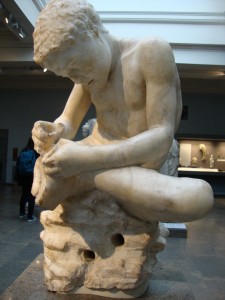

The Greece Wing of the British Museum

Another reason I loved it was on the pure artistic level. As a museum lover and art minor, walking into the museum facing the Greek statues and really analyzing them art historically was so amazing. I really took my time looking a few pieces rather than trying to see everything in the overwhelming collection. I noted the realism in the Hellenistic section of the Greece wing. I got right up close to the statues and looked at the small details, the way the flesh was rolled where the body curved, or the controposto (weight distribution), or the way the head resting on the elbow really had the right weight. Even the way the lighting on the marble gave it a warm yellow hue, almost like the warmth of skin and the human body, making the figures see that much more alive and real. Often I found myself inching closer and closer to a figure wanting to touch the marble, wanting to feel the coolness of it just to remind myself it was not warm flesh.

There was on statue of a small boy, Marble statues of a boy, the so-called ‘spinaro.’ This one was one of the most touching. The boy was pulling a torn out of his foot. And the expression on his face was just right, to show a little boy’s concentration and fascination. Having a little brother myself may have biased me towards this sculpture over others, and maybe it was just another thing in the museum that made me feel at home. But really, even the way to boy was crouched over suited the narrative of the piece.

On another note, the British Museum has so many connections to our course here in London. Aside from its fame Reading Room that relates to the literary history of this area, there is always the basic collection as a representation of all the different communities and cultures present. With a wing from almost every continent, the British Museum has very few things that could be considered wholly “British.” But at the same time, isn’t that really what we have learned here this past month, that NOTHING really is WHOLLY British? I think it is. In essence, the British museum encompasses our whole class and our final conclusion that there is no British identity. That there are only many pieces from many different elements of people’s lives that use to help with their personal identification.

Tags: Megan · Museums

September 15th, 2009 · No Comments

Identity is a concept that has never been a favorite of mine. I find that it is used too often and inappropriately. I have heard identity used to encompass individuals, cities, cultures, even nations, but to me how can this one word and concept be that encompassing? For me it is not all-encompassing. It is something decided on an individual level. Qualities that compose one’s identity can be shared on various levels, such as city, culture, similar interests, et cetera. Trying to label a larger group as a single identity, in my opinion at least, is impossible. Similar characteristics in individual identities found in larger groups such as a religion or culture are labeled as an identity. Technically this is correct, that identity consists of characteristics A, B, and C, which are all found within members of the larger group. My issue with this is that there is more to their identities than this all encompassing group identity. This is where I feel as though identity changes from a useful individual concept into a misnomer.

Our time here in London has cemented my opinion concerning identity. The city is a vast collection of numerous people and as such thousands of identities. It is wrong to try and label the city or groups of individuals here under one identity. Especially when you consider how quickly identities can change and how quickly they can be reassigned or misconstrued. Appearance is one way that identities can be misconstrued or changed. If one dresses in a certain way than their identity is predetermined before they are even allowed to introduce themselves. Relying on identity of a group to understand the individuals of the group is not a sure way of actually understanding them. Identity is a way that we attempt to label individuals and groups. As we explored various parts of London including the Hindu Mandir and Sikh Gurdwara, I found that we discussed their cultures and ways of life instead of their identity in London. It was too hard to give them an identity, but we could discuss cultural differences, ways of life and attempts to transition into British society.

Identity is something that cannot be relied on to convey thoughts on London. It is nearly impossible to label one identity for an entire group. Identity is on an individual level. Exploring London has helped me further understand what used to be my confusion about identity.

Tags: Kimberly

September 14th, 2009 · 2 Comments

When you think about identity the person you are, the person you wish to become you never truly recognize that ultimately you have no control on your identity. What makes up one’s identity; Race/ethnicity, gender, sexuality, class, job, degree? The list can go on forever, and the major commonality among all of these aspects of one’s identity is that they are all socially constructed. You never get to decide what you wish to be, and it is unique. Of course not anyone person in the world is the same, but an individual is never able to define themselves without conforming to society in one way or another.

In the novel Second Class citizen Adah is trying to escape her confined gender role as a woman in Nigeria. In order to do so, she flees to Europe in search for a better life. She discovers that her societal role in Europe is far worse than it was in Nigeria and she is further oppressed because of what her identity. If we examine the oppression that Adah faces in both Nigeria and Europe we can get a better understanding of identity. In Nigeria the only obstacle that Adah faced was the fact that she was a woman. Adah was a much respected woman in her society, but because of her gender she faced oppression that affected her subjectivity in society. It is this reason that led her to flee to Europe. However when she arrived in Europe other parts of her identity was realized. In Nigeria Adah was just a rich woman, but in Europe Adah was a middle class black woman. This realization of her racial identity is something she never had to acknowledge because in Nigeria she wasn’t a minority, but when entering Europe her identity becomes altered. In essence she has not control of her identity because identity is not self defined. Identity is defined by society.

Everyone in this world from birth is given their name, gender, and sex. As they grow they are allotted a certain number of social constructions to add to “their identity.” No one born in today’s world can exist without being defined by society, and even choosing to remain as an “other “or remained undefined you are still conforming to a societal role. The human race has become so compliant on social construction, that they have become our norm. And what makes matters worse is that so many people are unable to realize that by simply existing they are being forced to conform to society. To answer Jeyla’s question, Identity is always societal defined.

Tags: Anthony

September 14th, 2009 · 1 Comment

“Identity would seem to be the garment with which one covers the nakedness of the self, in which case, it is best that the garment be loose, a little like the robes of the desert, through which one’s nakedness can always be felt, and, sometimes, discerned.” – James Arthur Baldwin.

We all identify ourselves whether it be through our gender, sexuality, nationality, race, economic status. Sometimes we make up our identity but often we feel pressured to identify with a certain group in order to feel a sense of security and comfort although having a certain identity does not always guarantee one comfort with the majority of the society. It has taken me a long time to gather my thoughts on identity because it seems that many “categories” of identity are superficial. Therefore, whenever I discuss identity, I try to focus on the individual. On individual’s “comprehension of him or herself as a discrete, separate entity.” As James Arthur Baldwin stated, identity is a garment that most of the the time covers the true individual. By our need to identify oneself we limit our being.

Upon arriving to London, it seemed that most of the society identified themselves by simply their economic status. In a country where monarchy and class are in their prime, there seems to be a focus on whether one identifies as being in the higher, middle, or lower class. While being in London, we have been discussing the construction of identity for the individuals who have immigrated to England and the effect that migration has had not only on the first generation but on the second generation as well. We have read works such as White Teeth by Zadie Smith that explores the migration and adaptation to postcolonial Britain, where the identities of the characters are defined not only by their economical status but also by the color of their skin, their cultural beliefs, their religions, their upbringings. In White Teeth, the author decided to introduce a wide array of cultures present in North London and explore how they mixed in a country like England which is a country “with immigrants.” Englishman Archie Jones, the family from Bangladesh, the Iqbals, biracial Irie Jones who struggles with not only her identity, but her hair, Alsana Begum, the wife of Samad Iqbal, second generation brothers Millat and Magid who are expected to be unaffected by the Western culture are all part of this mix. Some of their challenges include keeping their traditions and religions as part of their identities. Yet again such task is very “superficial” where one assumes that religion and cultural traditions are not present if one is also adapting to their current country of residence. Second generation characters such as Millat, Magid, and Irie struggle between the expectations of their parents and the society with their own wishes and their own chosen identities. They were not able to wear “the loose garment” and shed their given identities due to their historical past whether it be their origin, national past, or family history.

Irie Jones is introduced to us as a biracial teenager a daughter of the Englishman Archie Jones and Clara Jones, a former Jehovah’s Witness. Being a teenager and wanting to escape her given identity and fit in with the majority of the English society, she goes as far as straightening her hair but literary burning all of her curly hair off. Her need to limit her being by fitting into one category or the other causes her struggle. As readers we are exposed to Smith’s recollection of Irie, her obsession by the typical white family, her constant need for the separation from her parents, her need to look different in order to attract male attention. Alsana Begum, who was also married to Samad Iqbal, struggled by having the identity of a Bangladeshi wife. Although we as readers can see Alsana trying to break the barrier of being a quiet, submissive wife especially when it comes to making decisions regarding her twin sons, she is unable to break the barrier. She is reminded of her role, her identity by her friends, her husband, and her children. Alsana’s story is a great representation of what masculinity meant in postcolonial Britain where male superiority has existed for centuries, it is even more interesting that she was an immigrant whose own culture also places a focus on masculinity. Therefore, her struggle with her identity can not escape her. Neither Irie nor Alsana are aware of their separate entities of being individuals. They are so caught up in the identities given to them by their families that they forget to live. They forget to be themselves. Their identities are the opposite of being fluid, they are trapped.

After trying to explore identity in White Teeth, I am still questioning identity. Is identity something that we ourselves choose or is it always the result of the society?

Tags: Jeyla

September 12th, 2009 · No Comments

This post is in response to the excerpt that Professor Qualls shared with us from his upcoming book. In this introductory chapter, he raises several key points which translate into our discussions about race, ethnicity and identification in London.

First, he uses the term “identification” rather than “identity.” I feel that this terminology is much more appropriate – even somehow liberating – in that it implies a choice and agency whereas the term “identity” connotes a sense of inescapability.

Second, Professor Qualls claims that “[a]s with memory, urban identifications are both internally and externally manufactured.” This can be seen in London, especially. The language barrier and cultural difference that immigrants inevitably experience coming to a foreign country certainly play a role in this “process of identification.” It is reasonable that immigrant communities would identify much more readily with a community that theirs their cultural, religious and linguistic traditions. It is the external forces, then, that cause problems.

Indeed, Qualls mentions that “[i]dentification can be either categorical or relational.” When outsiders (external forces) categorize or imagine relationships between immigrant groups where none might exist at all*, they are essentially “othering” those populations, isolating them from the rest of society and making it virtually impossible for any foreigner to feel comfortable here, let alone the possibility of “assimilation” – which I think is a completely ethnocentric idea to begin with.

It is not the responsibility of immigrant populations to adapt to the country in which they are residing, so long as they learn to respect that country. But this is a two-way-street. Locals must also learn to respect those immigrant populations which whom they share their space.

Particularly in London, these unique immigrant communities are what makes the city uniquely “London.” Or, to, yet again, quote Qualls: “maintaining past traditions was essential to the stability and happiness of the population, which in turn would reflect well on the central regime.”

*Some of you may remember the story Andrew Fitzgerald, Andrew Barron and I shared with you at the beginning of the course: At our market in Elephant and Castle, we witnessed an altercation between a darker-skinned customer and a white, cockney fruit and veg vendor. The vendor called the customer a “Paki” and obviously had no legitimate basis for determining this man’s ethnicity. Just because the customer had darker skin, the cockney vendor “related” him to a Pakistani. This is a dangerous comparison which only serves to fuel racism.

Tags: Anya

September 12th, 2009 · 1 Comment

How do you write about something that inspires you? How do you describe something that reminds you why you love to create? How do you interpret something that teaches you the importance of people of all classes? Well I guess you could start by giving it a name: The Pitmen Painters play at the National Theater. Now I am not a theater person myself. And although we have seen quite a few plays up to this point, Troilus and Cresida, Alls Well That Ends Well, Arcadia, none of them have sparked my interest enough to blog about them until the Pitmen Painters last night. It was so much more than a play about the struggle of the lower classes, or the search for IDENTITY in London society, or even the importance of art to modern society; it was about DISCOVERY. It touched on the heart of what it meant to strive for more, without even knowing you were striving for more, yet knowing you DESERVED more.

While the theme of artistry was what I related to the most in the play (which I will go into more detail about later on), the idea of class and personal identity separate of class identity was another theme I found moving. The class system has traditionally been very prominent in British culture. As we have seen in our various reading thus far in the class, it is still very much an existing prejudice here in London. Although we have spent most of our time studying the prejudices against many immigrant and ethnic communities of more middle to lower classes, this play focused on the disadvantage lower class uneducated miners. As these men took this art class, and began to create and fmailiaritize themselves with art, they still tried to retainer their IDENTITY as miners. Yet, when their instructors strives to use them to prove that all “lower classes” are capable of artistic achievement, the miners reject this, and strive for their own individual identities as artists, separate from other people of their class. In this way I think that the play was able to capture the essence of what we have learned from our readings, visiting various religious sites, and seeing the immigrant communities and markets. Essentially, how does one balance personal identity with group identity. At what cost to the group—whether it be religious, class, ethnic, or other social structure—does one get to be an individual, or a Londoner? Or a native? Or British? In the same way that these miners tried to maintain both identities and form a new one, migrating and immigrant groups to London must find a balance between who they were in their group, and who they want to be to fit in in London. The play also touched on a another more personal level. As an artist myself, I found the play to be especially moving on an artistic level. Since I have been to London, I have hardly drawn and have certainly not embarked on any larger scale artistic projects. There have been reasons and justifications of course, too busy, too tired, not enough space. But Oliver’s struggle to balance the pressures of his role in society as a miner, with his desire and growing passion for art and learning reminded me that art is more than a hobby. When Helen Sutherland confronts Oliver about his artistic future, she does not try to sway him by reassuring him of his talent or artistic ability, instead she tells him that he “thinks like an artist.” Art is not a thing you do, it is who you are. I found this to be one of the most touching parts of the play. It reminded me why I create. It’s not because I like to, or want to, or even because I am good at. No, I create because I have to. ART is not something I do, it is WHO I AM.

If you’re interested in my own personal art, check out my weebsite: MNL.

Tags: Megan · Theatre

I feel very fortunate to have been to both a Sikh Gurdwara and a Hindu temple in such a short period of time. Truly there are not two better examples of divergent immigrant communities than the Sikh and Hindi. Both religions originated from South Asia but due to differences in their philosophies, have taken to life in England quite differently. The followers at Wembley’s Shri Swaminarayan Mandir seem eager to embrace life in England, while the Sikh Gurdwara in Southall seems more intent on just existing wherever they are. Have these two religions been changed by England, or is it something about their inherent beliefs that have created these two different situations? Unfortunately for this blogger, the answer is: both.

A possible argument can be made for how long each religion has existed. In terms of age, Hinduism is one of the oldest religions to still be widely practiced in the world. Sikhism on the other hand is only an infant in comparison, starting around 1500. However, we cannot judge these two communities based on how long they have been in existence, but rather how long they have existed in their new homeland. Living in a country unlike India, there have undoubtedly been compromises that both religions have had to make in order to survive at the minimum in England. For example, followers of Hinduism in England have to come to terms that many of their non-believing coworkers, neighbors, etc. are very likely to have beef in their diet. On the other hand, Sikhs strictly forbid any kind of abortion, and yet must live in a country where it is tolerated. Therefore, we must consider not the original religions of Sikhism and Hinduism, but the new Sikh/British and Hindu/British identities they have certainly formed. According to the BBC (and their respective links here and here), both the Sikh and Hindis had their first large waves of immigration to England at around 1950, therefore we can not only say that both communities has the same amount of time to develop, but were affected by factors of the same time period. The differences in how their communities have adapted then must be caused by fundamental differences in their religion and how the reacted to life in England.

Thankfully, there are more than enough differences between both their religions and their England-based temples to ascribe these differences to. The largest of these differences is each religion’s sense of humility and how in turn that mentality changes the way each community acts in a capitalist society. As I was guided around each temple with my classmates and was able to look at my surroundings, this factor immediately struck me. The temple itself was furnished very modestly. While there were some places that were elaborate, the most impressive room was the main prayer hall. Although this was the place that an entire of community of Sikhs met to pray, the room was meant to hold the Sikh prayer book, not take away from it. To do this, the entire room was draped in white cloth and the only vibrant color in the entire room was displayed around their holy text. While the building was quite large, every part of it served a function and according to our guide cost around 17 million pounds.

In the case of the Gurdwara, the people who worked at the temple did not even have someone who was trained as a tour guide for their temple. The person that ended up showing us around was purely a student of the religion, and talked to us as such. The focus of his talk (from what I could hear, as he was speaking almost directly to Professor Qualls) was on the philosophies of his faith. What seemed to matter most to the man was the Sikhism’s emphasis of community and how those that followed the religion were part of the community without prejudice. The idea of a tightly knit community seems to be just what Sikh’s in England desire. Although they are immigrants just like the Hindis, they are without a doubt the minority religion of people from India, with there being slightly less than twice as many Hindus than Sikhs. In order to retain their relevance within England, it seems that Sikhs have pushed idea of a unified Sikh community to the level of the 5 K’s, five items that represent the pillars of Sikhism. While caring for and protecting the weak has always been a part of the Sikh religion, it would seem that in their immigration to England, Sikhs expanded this ideal in order to protect their people who in an instant became an even smaller minority than they already were. In addition to wanting to preserve the Sikh community, it seems that the philosophy of Sikhism does not mesh well with British capitalism. Take for example when we were told that we would be getting a free lunch. Most of us couldn’t understand why a temple would give out a free lunch to anyone who came to the temple. Our incredulity was well justified, as it was hard to imagine a group of people working towards pure charity rather than profit. It is likely for these reasons that Sikhism in England has not matched Hinduism in cultural influence.

Some of the students grumbled about how some of the money that went towards building the Gurdwara should have gone to the surrounding community, but those grumbles only fell to the wayside when we entered the Hindu temple. Although the Gurdwara was a large building, the Hindu temple looked to be almost twice as large, the reason for that being the temple’s head-first dive into capitalism. Upon entering the temple, the first thing you are immediately greeted with is the Cultural Center’s gift shop. The temple was also able to provide an actual tour guide who in many ways was the opposite of the Sikh guide. Instead of explaining about the fundamentals of Hinduism, the man instead explained about the magnificence of the building we were in, and how the materials that it was built from came from only the best places in the world. As a class we were shocked by the 16 million pound cost of the Sikh temple, but it is easy to imagine that a building of the Hindu temples grandeur easily cost hundreds of millions of pounds. While it seems that the Sikhs wish to believe in charity and modest (Pride is actually one of their five “vices”), the Hindus have no problem proving to everyone how great they are. In a country where it is up to each person to create his/her own success, Hinduism seems to be more of a fit than Sikhism.

While we now can possibly guess the reasons behind how these two different religious communities act, there is still the question of reason. Are these communities acting as such in order to assimilate with British society, or are they just trying to survive? It seems that each of the religious groups have chosen different paths, as the Hindus aim to thrive and the Sikhs simply want to exist. Is one choice more effective than the other? Will the Hindu’s give up too much of their beliefs in order to succeed? Will the Sikh’s reluctance to reach outside of their community force them to fade into irrelevancy? Only time will tell, but we can be certain that England will keep calm and carry on, with or without them.

Tags: Paul

It is strange to think that we have only been in London for three weeks. We have packed enough into our days to make it feel as though we’ve been living here all summer. I realize that three weeks is hardly sufficient time in which to study the culture of a city, especially when said city has been around for 2000 years. All the same, our quest towards understanding the cultural significance of the modern city has brought us fairly far along. We are now being asked to define the identity of the people of the city of London.

I have a few problems with this question. How can we define something that is infinitely changeable? Modern society is an amalgam of different parts; British culture is, to use a term hitherto heard only in the realm of AP U.S. History, a “melting pot” of peoples. The identity of the British people has never been a fixed thing. Whether due to the Britons, the Romans, the Saxons, the Normans, or now the influx of various Indian and Afro-Caribbean peoples, the influences that effect British culture are constantly shifting. So too are the identifying characteristics of the citizens of this country.

I believe that the people themselves cannot be identified. With influences coming in from so many different cultures how can we pigeon-hole them all into one all-encompassing character? I would rather consider the identity of Britain as a country, not as a people. The people influence the identity of the country, not the other way around. If I was asked to provide images of what I believe defines Britain’s identity many pictures would surface. Sure, Stonehenge, Westminster Abbey, St. Paul’s Cathedral would all make the list. However, after many of our field trips I would add the Sikh Gudwara, the Hindu Temple, the smells of roasting food wafting out of Chinatown, and the costumes, and colors, and the sound of steel drums and rock music blasting out of the Notting Hill carnival. These brief snatches of cultural differences morph together to form the character of modern Britain while the people themselves retain their individual identities.

What interests me more than my opinion, is the opinion of the individuality of the British people. Reading Salaam, Brick Lane opened my eyes to just how differently these cultural discrepancies can be perceived. Tarquin Hall is, for better or worse, obviously fascinated by the residents of Brick Lane and the additions they bring to the identity of Britain. However, the other characters (Mr. Ali, Sadie, and some unnamed Cockney cab drivers to name a few) had wildly different opinions. The Cockney cabbies viewed all immigrants, whether they’d been in Britain for years or days, as invaders that had no right to call themselves Englishmen. Sadie considered any and all immigrants from India and Asia as not fit to live in Britain, and even Mr. Ali, himself Bangladeshi, saw all the new immigrants from his own country as ignorant, uneducated hicks. He had lived in London for thirty years and was for all intents and purposes British. His children were born in London. They are British citizens. Yet to those who had been here longer he was just as ignorant and uneducated as the newly arrived immigrants from Bangladesh. What none of these characters stopped to consider is that their ideas, their cultures, their different religions are all effecting the current identity of the country as a whole.

Whether immigrating from India or Israel, Romania or even the United States, every new person changes the identity of Britain a little. While I don’t believe the identity of the British people as a whole can be defined, we can discern the character of the country in this moment. Soon, however, it will change again, as influences pour in from other parts of the globe and other ways of thinking.

Tags: Campbell