September 11th, 2010 · 2 Comments

London’s diverse museums all have an element of British imperialism. The three which best show this are the Wallace Collection, the Sir John Soane Museum, and the British Museum. Yet, each takes a different approach to them: the British Museum is the standard artefact with didactic label, the Soane shows the spoils of an imperialistic age in the wonderful cabinet of curiosities method, and the Wallace Collection arranges its collection as a wonderful combination of the two.

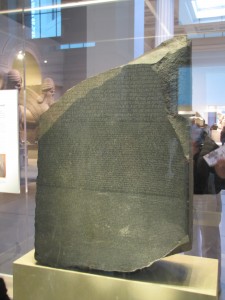

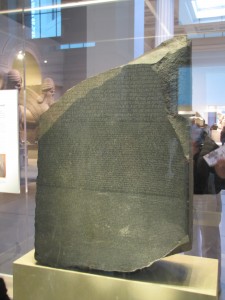

The Rosetta Stone, which has been a centerpiece of the Egyptian repatriation demands.

We’ll start with the British Museum. Perhaps the most controversial collection because of the Elgin Marbles, most of the collection could probably be at the center of a repatriation argument if a government decided to challenge the museum. Instead of noticing that the museum was a shrine to British imperialism, my first thoughts (once I pulled myself away from the medieval galleries) were about the museum’s role in the ongoing battle over countries reclaiming their artefacts. My general beliefs on repatriation are simple: the works belong wherever they are going to get the best care, which, unfortunately for the vast majority of the ancient objects, is not in their countries of origin. For example, there is no way that Egypt can assume responsibility for its antiquities; the ones there are deteriorating alarmingly. While Hawass has done a good deal for Egyptian antiquities, their facilities still are nowhere near those of the British Museum’s facilities. Furthermore, shouldn’t objects that have influenced the whole of history be where the most people have access to them? Surely that is here, in London, not in Cairo?

One of the Elgin Marbles

Unfortunately, that argument is no longer valid for the Elgin Marbles (although, while not as an unpredictable environment as Egypt, Greece does have its problems which could threaten the marbles). Greece has a new acropolis museum that is a perfectly suitable house for the marbles. So, why do I still believe they belong in London? Aside from the whole no-objects-can-leave-England-law and the incredible galleries they are currently housed in, there a couple of reasons. Firstly, their provenance, unlike that of the Italian krater the Met repatriated to Italy, shows them to have been purchased legally versus outrightly stolen. We may not agree with the way they were handled in the 19th century, but because we have a different understanding of the proper way artworks should be sold/purchased does not mean we can go back and make amends with everything. The world’s great museums would be emptied. Secondly, where they are now, they are more accessible. If Greece didn’t have almost as many as the BM, I’m sure everyone would feel differently about the issue. (Well, except for Greece, which would still demand them all, even in the BM only had one.) Because repatriation has become such an important issue, I do believe that even if English law did not forbid it, the marbles would never go back to Greece because once the BM accepts Greece’s arguments, the watershed for repatriation will be open and museums will be scrambling to quadruple check their works’ provenances, possibly wasting valuable resources.

It was only after my second visit to the British Museum that I wondered about some of the works’ provenances. However, from the moment I stepped into the Sir John Soane, all I wanted to do was demand to see some of the provenances of various works, as well as pick up the objects to examine them and the way that they were removed from their original locations. I think part of the reason that it took a second visit to the BM to question it was as one of the leading museums in the world, it has more authority as the stellar, but smaller, Soane. The traditional layout of the BM commands respect, whereas the Soane is easy to mistake for a pile of junk haphazardly arranged. Except, it is the exact opposite: the Soane has incredible pieces. (I could have died of joy looking at the random Gothic bits.) Because of the arrangement- a life size cabinet of curiosities- it is easy to forget that all of the works can point to the achievements of Soane and his time, noticeably imperialism. When walking through, one’s mind is trying to take in everything and is not assisted by didactics, the larger picture is sometimes lost, unlike at the BM, where the layout and didactics remind you almost constantly that while the museum is “British”, the majority of the collection is not. Furthermore, the Soane’s arrangement allows one to feel closer to the objects. Indeed, it is easy to get away with a close examination of the work on the wall and touching them. In the BM, the viewer is often annoyingly separated from the work by class or a rope barrier.

If the BM is arguably the most controversial museum because of its collection, then the Soane is the most overlooked for controversy. Lots of the works were supposedly removed from crumbling sites. Were the sites crumbling before or after the works were removed? Did the dealers have explicit permission? These questions are largely overlooked; in fact, lots of information is overlooked, which adds to the feel of a cabinet of curiosity.

The Wallace Collection

The Wallace Collection is like the Soane in that it started as one cohesive collection and has grown, as well as that it shows the way the works were staged by their original collector. However, unlike at the Soane, the Wallace Collection does an amazing job of showing lots of works in a way that is not as overwhelming. The collection is mostly housed in period rooms, which add to the atmosphere of the museum, greatly enhancing the works. Instead of wondering about whether the objects should be repatriated, the collection sets up the works in such a way that the viewer is not distracted by theoretical questions on museum practices. (Unless said viewer gets bored of Rococo and armour.) Furthermore, the collection focuses on European art, which focuses it a bit more than the other two museums. If anyone is interested in armour, the Wallace’s collection is superb and world-renowned. Instead of wandering around the museum pointing to works I wanted to examine for causes to repatriate, I wandered the Wallace wondering why certain works were hung together and why anyone would want rooms upon rooms of Rococo art, much less why I was wondering around them when there were three outstanding armouries downstairs that were calling me.

Yet, part of me wonders if Britain didn’t have it’s imperial past, would I be able to see this quality of art and artefacts. If I were able to, would I wonder about the provenance and history of each work as much?

Tags: 2010 Stephenie · Museums

September 11th, 2010 · 1 Comment

Throughout our time here so far, I’ve been to museums that I’ve loved and loathed. Regardless of how I felt about the collections, each museum seemed to say something about England, as well as demonstrate amazing educational programs. (I’ve decided to tackle the issue of museums in two separate blogs. I’m not going to deal with repatriation and provenance, both issues have been on my mind a good deal at a couple of the museums, most noticeably the British Museum and the Sir John Soane museum, in a second blog. This one will be more general and focus a bit on educational programming within the galleries.)

Firstly, thinking back to over two weeks ago, the Greenwich Observatory was an interesting museum. It wasn’t one of my favourites, partly because of the collection, most of which I did not really care for. However, the excellent interactive bits throughout the exhibits were engaging. It did a good job explaining the importance of Greenwich time and it’s relationship to the development of shipping. (I probably know more about longitude now than I ever needed to know.) Unlike the other museums I’ve visited, the achievements it highlighted, were an integral part of the build-up to imperialism vs the spoils of imperialism.

Prime Meridian

The Tate Modern would be my next least favourite. I like some modern art, but it is not normally my first choice to spend an afternoon admiring. (Unless it is a Kandinsky show.) Throughout the Tate, I felt that some of the space had been wasted, especially on the floor where the membership room was located. The main galleries were nice, but offered very little in terms of supplemental didactic materials that could further engage the viewer- all of that was outside of the gallery. While the interactive bits were very interesting, they could easily distract from the art itself. (The seemingly endless reel of video shorts seemed to confirm this.) Yet, I admired the activities for the younger children which engaged them and put the art on their level. By separating the modern art from its other collections, the Tate seems to promote its standing: it is worth more than a gallery add-on in the main building.

The Tate Modern

The Guildhall Art Gallery, by comparison, offered very little interactive displays. By the time I had visited here, I was so use to in-depth descriptions, a wide audience, crowded galleries, and fun didactics, that the seemingly empty gallery caught me off guard. It was nice to see the Roman Amphitheater; the room’s set-up was incredible with recreations of the gladiators. However, the gallery’s art collection was lacking. It mostly seemed to be lesser works of second-tier artists or smaller copies of major artworks created later in an artist’s career. I believe that the gallery was trying to show the positives of British art in the last 200 years, but the gallery failed in this mission because it failed to hold one’s attention for long. Furthermore, the special exhibitions were too text panel heavy. (Balance seems to haunt this gallery.) The panels were informative, but when 3/4 of a panel is devoted to reproducing a picture which is hanging next to the panel, there is a problem. The viewer is drawn to the reproduction, not the actual artwork, defeating the point of the gallery.

The National Gallery is one of my favourites that I have visited, partly because of the Wilton Diptych and partly because there is one spot where my favourite Holbein and a Vermeer are both in one’s line of sight. The collection is outstanding and the works seem to represent the majority of art history. Well, my favourite bits at the very least. While there are not as many interactive activities, the didactics are engaging and there are educational options available. Instead of only seeming to be the spoils of imperialism, the collection has a truly British feel, partly because so many of the works are ones that directly relate to English history rather than the history of far off places. Furthermore, it’s easily accessible and not hidden like the NPG; it’s prominent position on Trafalgar Square also helps with accessibility.

The Wilton Diptych

(For more information: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/english-or-french-the-wilton-diptych)

The Victoria & Albert would be tied for my second favourite museum thus far with the National Gallery and the British Museum (which I’ll discuss in my other museum post). I spent almost 2.5 hours in the new Medieval and Renaissance Galleries, which were not only gorgeous, but held some incredible pieces. (Can I please just have one grotesque figure?! Just one…) Several people have noted that the sheer amount of stuff in the museum is overwhelming. Outside of the M&R Galleries, I would agree with this. Here, the museum seemed to be addressing this issue, trying to open up the galleries and spread out some of the pieces. Furthermore, the excellent listening stations found throughout the galleries were a perfect mix of in-depth and cursory information, allowing the viewer to pick and choose the information they heard based on their interests. (Highlight: listening to Gregorian chants while viewing the different altarpieces, all of which were stunning.) The V&A proudly displayed artworks which combined to tell the story of the world through art. Unlike the British Museum, it did not claim to be a solely British institution, which I think in some ways helped make the museum a more open place. Furthermore, because it is an artistic school as well, it’s collections are all educational, adding to a different responsibility for its didactics and what is should be collecting. It filled gaps through its amazing replicas gallery, which included some of the most famous works ever created.

Misericord, Victoria & Albert

When taken together, the museums not only provide one of the most stellar examples of museum education in practice, but also serve to tell the triumphs of the British Empire and to highlight the triumphs of the larger artistic international tradition. If London is a city of the world, then its museums reflect this.

Tags: 2010 Stephenie · Museums

September 3rd, 2010 · 5 Comments

As someone who wants to work at a museum, I enjoy different ones (even on a day where I visit four) and seeing how they formulate their exhibitions and present their collection. I also enjoy seeing how children interact with museums, as I want to combine museum education with my love of medieval art. The National Portrait Gallery, however, was not the best museum I have been to thus far. In fact, the quality of the art aside, I was largely disappointed.

Going in, I expected the portraits to be largely of the elite ruling class and others who had some power, whether political, artistic, or scientific. The collection was predominantly white elites (mainly males). This is understandable, as that was who was most likely to be in a position of power through the majority of England’s history. While portraits are not as readily available of the lower classes, they do exist. The NPG seemed to overlook this fact until very recent history. (Even then, the portraits chosen to be featured in the permanent collection tended to have an element of celebrity rather than being chosen for the lesson they can teach about daily life in a given period.) After finishing the Tudor section, my interest levels were in automatic decline and the museum had very little to reverse that. Its one redeemable feature was the interactive computer stations that went past the simple didactics in the collection. Yet, even that was lacking: it was written for an average adult.

There should have been a version of the interactive stations specifically designed (and easily accessible) for children. (Supposedly there was a map for children, but I did not see any families with one. Did anyone??) The NPG is a family destination: tourists (who make up a presumably large part of the museum’s audience) do take their children there (I witnessed several families) and there needs to be something more that acknowledges this more interwoven into the permanent collections. Instead of a dad timing his son to see how long he could walk from one end of a wall-long portrait to the other, I should have witnessed a dad engaging his son with a museum map for children. (This is something that I have seen in almost every other museum on this trip, which made the issue more obvious to me. If a family chose not to use the available map, then the museum still has the responsibility to help engage a wider audience.)

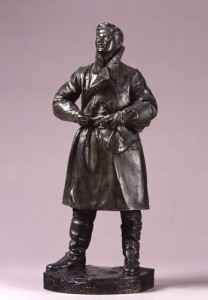

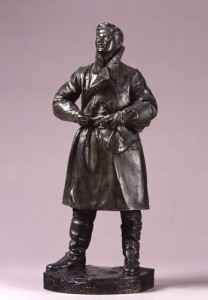

One of the few portraits that spoke (amidst the celebrity portraits) to me was a small model of a full-scale statue of Albert Ball by Henry Poole. Ball, a WWI pilot, shot down 43 enemy planes before being killed in action. At 21, he is one of the few people who appeals to a largely universal audience: English viewers for his patriotism, history buffs (WWI geeks specifically), art historians for his glimpse into war-era art, younger children of all backgrounds because of his heroic story (everyone loves a good hero, yeah?), 20-somethings who wonder if they can make a difference, and wanderers because of the persona that radiates from the work itself, capturing the power and passion of a young hero. Yet, even the portrait I liked the most stuck true to the NPG’s “requirements” for display: white and elite. (The portrait was given by Ball’s father, Sir Albert Ball). It did, however, lower the average age of the collection’s sitters by a few years… Picking a younger sitter for a comic book-esque family guide would have engaged the children. Who better than a WWI hero to be the leader? (This could easily be inserted in the visit with a small map and identifying pictures on didactic panels to let families know that a certain portrait would be more interesting for a younger audience.)

Albert Ball by Henry Poole, 1920s, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait.php?locid=50&page=1&rNo=6

After visiting the NPG’s education website (http://www.npg.org.uk/learning.php), I realize that there are educational activities available for families; I do want to give them some credit. However, I wish there were more in the gallery on a daily basis rather than on weekends or just for school groups.

To recap. The negatives: a lack of engaging material (even the interactive bits got boring after a short while, and specifically for the younger members of the audience) and a less than diverse “cast” of sitters. The positives: the collection itself (overall stellar artworks) and the opportunity to think up some (hopefully) creative activities that if I were the Curator of Education I would consider adopting. (Who knows? Maybe I will borrow these from myself in the future at an internship…) Oh, one other thing, what was up with the atrocious color scheme in the Regency wing? It detracted from the experience for me because there were times I noticed the wall color before the portraits, which should never happen, especially at a major national institution!

Tags: 2010 Stephenie

September 3rd, 2010 · 1 Comment

Upon entering the National Portrait Gallery at its opening, I was struck by the immense size of the collection. For an art museum that had so narrow a focus, I was not expecting three full floors of work.

Beginning at the top floor, the museum took a chronological approach to the presentation of the portraits. One started going through rooms filled with portraits of the Tudors and ended observing portraits from the last decade on the bottom floor. The collection portrayed royalty, politicians, writers, musicians, artists, scientists, and other notable figures. Some of the artwork was surprisingly cynical in nature, while most were glorifications of their subjects. The term ‘national’ clearly was referring to the United Kingdom and not just England, given the presence of figures like James Joyce. Also, the collection seemed to feature figures that were mainly associated with the UK, as Handel was featured despite the fact he was born, and grew up, in Germany. A clear emphasis was placed on the rich and famous, while relatively none of the works portrayed the lower classes. Also, no one associated with the British Empire, such as Gandhi, was included.

The portrait I decided to focus on was that of Sir Francis Drake, located on the second floor. As we were not allowed to take pictures in the museum, I have provided a link here: http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw01932/Sir-Francis-Drake?search=ss&firstRun=true&sText=sir+francis+drake&LinkID=mp01357&role=sit&rNo=o

The painting of the famous navigator is not particularly flattering or, quite frankly, well painted. He stands before the observers at an odd angle, holding an oddly (aka poorly) shaped globe resting on a table for balance. Drake is dressed in a garish pink outfit, with a cape that looks too stiff too be real. His arms appear to be different sizes, and legs appear to be much larger than his torso. Looking at his face, his cheeks appear to be inflated, making him look more like a comical figure than the daring naval admiral and pirate that he was. He stands with a slight arrogant look, as if ready to take over the world (something his nation would effectively try to do in the coming decades). Looking at the portrait, it is hard to get over the poor quality of the painting. With the dismal proportions, poor color scheme, and lack of inspiration, you would almost wonder if the artist is unknown because he or she was ashamed of the work.

I picked this painting because I was so struck by its poor quality, particularly in relation to many of the other works in the National Portrait Gallery. One could almost see the work as an accidental representation of the British Empire’s colonial overreach. With the country moving so quickly to expand, one can understand the rush to make heroes out of these new explorers, evident in this portrait of Sir Francis Drake. Unfortunately, just as the Empire was built on a weak moral foundation, the picture falls victim to poor artistry. Therefore, one could read the portrait as a representation of the weaknesses of imperialism… or one can just see it as a really bad painting.

Tags: 2010 Andrew

January 22nd, 2010 · 1 Comment

So this is by no means what I am doing or my presentations; however, I felt it would be of interest to you folks anyway. Over winter holiday, I went to visit the MHS (Museum of the History of Science) to see their exhibit on the art that has come out of steampunk movement, both and England and worldwide. It was fantastic, and I definitely recommend it as it is running until February 21st.

For most people, the idea of steampunk (and the movement surrounding it) is quite foreign, so I will do my best to explain what I believe it to be. I stress that this is strictly my interpretation, as it is a severally decentralized idea with many interpretations. The way I see it there are three major aspects of steampunk. The first being the history surrounding it. The second is the art that has come from it, both literature, music and painting. And the third, is the DIY(do it yourself).

It is difficult to pinpoint when “steampunk” first originated. The OED places the term steampunk around 1987 by Jeter in Locus; it being based off of the previous genre of cyberpunk, which is is an entire different subject. Despite its fairly modern coinage, steampunk has arguably been around since the Victorian era (whence it is based). Works from Jules Verne to H.G Wells sought to look into the future of technology, using what understanding they had around them. In more modern works, steampunk looks at modern technology and wonders how the Victorian era would have created it. How would our society have benefits or been illed if the social atmosphere of the 1800s had continued to present day?

As the art exhibit showed, steampunk is still inspiring people today to push the boundaries of what art is. There were beautifully remastered keyboards, fitted with wood panels and type-writer letters, a light fixture that was simply amazing. There were, however, less practical aspects such as a teleportation device. This blending of functionality and impractically is a keystone of the steampunk dogma. It doesn’t truly matter if something makes sense; it is almost as if steampunk asks us to question the rationality of our modernity.

The exhibit itself is very well laid out and organized, and it is a great forum for learning more, seeing its capabilities, and talking with international artists about their motivations and techniques. If anything it was great simply for the people-watching aspect. I will not embarrass myself by putting up the picture of my get up, but needless to say I went in full nerd glory. What was nice about the experience was that dressed up and not dressed up basically gave each other the same looks of curiosity– anthropologists observing a foreign culture. It felt as though there was a mutual understanding of appreciation and acceptance.

What I found most amusing about the whole experience was the music that has come out of the steampunk movement. As with many DIY groups, the instrumentation was weird to say the least. While it wasn’t at the show this guitar is probably one of the neater things I have seen. You even have entire bands devoted to steampunk such as Abney Park.

Do it yourself comes into play for obvious reasons as there isn’t really a plethora of steampunk outlets. But it also works as a means of expression. Once you’ve sown together your first frock coat, or even your first button, there is a strange sense of pride seldom found in modern activities, not unlike finishing a painting or running a 5k. Obviously with our budges as they are arts and crafts probably aren’t on the top of anyone’s list, but it is interesting to see how much you can create with recycled goods. While it is by no means on par with Dickinson’s removal of the lunch trays (or the creation of a sushi bar), I would argue that steampunk is up there in the sustainability zone.

I think my only quarrel with the whole idea is that people often forget about the societal norms of the Victorian era. As we have learned there certainly were social reform movements going on through Queen Victoria and Prince Albert such as the opening of parks and the support of artistic movements. Overall, however, the Victorian era was set by ridge social ques and mass oppression. At the exhibit a young female artist tried to explain to me how the Victorian era was a period of femenistic empowerment, which is absolute bollocks. The idea of sexual equality is something only sense in period pieces when a director needs to have a head strong, coy female lead so as to attract a larger demographic (cough Guy Ritchie cough). For that matter, sexuality in general was severally hampered. Showing your calves, man or woman, was considered an outrageous fopaux.

Much as its brother genres of the science fiction realm, it allows us an interesting thought-experiment and temporary escape. But the modern interpretation of steampunk has drifted further away from its Victorian roots. This decentralization is both a blessing and a curse, as it allows for vast array of artistic expression. It is for that reason that it is so amazing something like the exhibit at the MHS could have been put together and still seem cohesive.

If you’d like some more info on steampunk feel free to ask me anything. I don’t claim to know too much, so here are some sites that know better.

http://www.steampunkmuseumexhibition.blogspot.com/

http://brassgoggles.co.uk/blog/

cheers

Tags: Andrew R

September 19th, 2009 · 4 Comments

The Sir John Soane Museum was the last thing I was able to squeeze in before leaving for Norwich. The museum was interesting, however I do not think it was very educational. It was essentially just peering in on Sir John’s house and his collection, but there were very few signs telling the museumgoer about the relics that were scattered around the house. The architecture was amazing as was the collection, and like most of my classmates I would love to live there if it were not so narrow in parts of the house. However, I do not see its relevance to the course. Why Professor Qualls did you choose to throw it onto our list? I am having a hard time saying anything about the museum because I do not see how it fits into the theme for this class. Honestly, I have learned more from the museum’s website than I did in the actual museum. The website has the entire collection on it with blurbs about the history of each piece. However, unlike most other museums the website does not display a mission statement or any of the museums goals. I believe that every museum should have a mission statement. This makes helps the curators organize exhibits, artifacts, and information panels. With out a strong goal relics are just crammed together, like in the V&A, or there is very minimal educational material, like the Sir John Soane Museum.

I never thought of myself as particularly interested in museum studies, but after visiting all these museums I can see what foundations need to be there for a museum to work. Out of all the museums we visited I feel that the Docklands museum did the best job in presenting and preserving its artifacts and its history while doing a great job educating its visitors. The museum has a clear goal: to educate the public on the history of the docklands. It also has a clear pathway that one can choose to fallow at their own pace, while the British museum had no path way and tended to get very congested at various parts of the exhibits. These large crowds of people greatly affect the safety of the artifacts that the museum is trying to preserve. People should not be allowed to touch, feel, hug, and take pictures of ancient Egyptian sculptures. These crowds are also not good for the safety and education of the museumgoer. Old women or men should not have to be pushed around to have a glance at the mommies, and one should be able to easily see and read the information panels next to the relics if they choose to do so. At least The Sir John Soane museum limited the number of people in the museum at one time in order to protect the artifacts and the people (as it would probably be a fire hazard for too many people to crowd into that building). Maybe the British museum can look to the Soane museum for advice and limit the number of people in the mummy room at one time and increase security. While perhaps the Sir John Soane museum can fallow the British museum’s model and provide more information on the artifacts within the house.

Tags: Rebecca

September 15th, 2009 · 1 Comment

I believe that this is a very important question that we must ask ourselves in order to understand museums and London in general. England is one (or maybe the only one, I am still trying to find out) of the countries in the world that has so many big museums which you can enter for free.

Apparently, museums in London used to be private, but in December 2001, the 15 main ones, such as the British, the Imperial War, the Tate Modern, were made public by Tony Blair’s administration. Many supporters of ‘New Labour’ considered this policy to be one of the major achievements of the party’s agenda. The government at the time was seeking to increase museum audience across the multicultural spectrum. They thought that by making the museums free of charge, they would receive not only a larger audience, but a more diverse one. Why museums? As I mentioned in an earlier post, museums have proven to articulate the ideology of the state and work as institutions that reclaim the national identity, much needed to rule a country.

After some time, research showed that, while making the museums public had increased tourism, they did not attract new audiences, but rather more frequent visits by the same crowd as before (mostly white and upper middle class art lovers).

This makes me wonder why there are so many people in London who might have never attended any of these museums and why not? They’re free! But giving further thought to the matter, I realized that the museum is not going to receive more Africa-descended people by exhibiting African masks. The same way Latin American people in London are probably not going to go to the British Museum’s exhibition of Moctezuma. The Victoria&Albert Museum’s fashion exhibit attracts young designers, but that is probably the most “exotic” audience they have.

What is access to culture then? How do we define it? It is certainly not only a matter of financial access, as we can see. I think that, again, it has to do with how people are located in the structure, and how much cultural capital they have. Once more, it might also be strongly related to being able to afford the time to visit a museum.

Tags: Azul

September 15th, 2009 · No Comments

-

-

Regents Park

-

-

Christ’s Church

-

-

The Silver Exhibit in the V&A

-

-

Having a Good Time at the Fitzroy

Like many of my classmates I decided it would be worthwhile to summarize all of my discoveries this month in London. During this post I will focus on six main themes found within London: Parks, Churches, Pubs, Other Religious Institutions, Theatre and Museums.

Parks

Each park that I visited had its own distinct characteristics that separated it from any other. Green Park was the first I visited and after perusing a few others, I realized there was nothing that exciting about it. Located right across from Buckingham Palace, Green Park certainly provides a good place to go and take a break from the busy atmosphere of the area. Besides this however there is not much going on and I would recommend that potential park goers walk the extra distance over to St. James Park.

In addition to the large number of waterfowl heckling people for food which offers consistent entertainment St. James offers some picturesque flower beds throughout and various monuments along the way. It has the relaxing atmosphere of Green Park with a bit more excitement sprinkled in.

Regents Park offers a completely different feel from Green or St. James. Located in a separate area of London, Regents Park has a history of being used by a higher end crowd. I could tell this immediately from the feel of the park. The decorative shrubbery and elegant architecture throughout gave me a feeling that Regents is not as well used as other parks.

Since I was one of the members of the Parks group that gave a walking tour of Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens I could go into a lot more detail about these two green spaces but I will choose not to in an effort to be concise. In summary Hyde Park is the largest green space in London and is often used for larger events such as concerts, festivals etc. It also contains a large number of monuments throughout including the 7/7 memorial and the Diana Memorial Fountain. Kensington Gardens is home to a variety of key monuments but is not as well trodden as Hyde. Overall it makes for a quieter atmosphere, more conducive fo reading or “snogging”.

Regents Park were my two favorite green spaces in London. Regents, is both beautiful, and extremely large and I continually felt the need to go back and explore. Kensington Gardens appealed to me in that it was quainter than Hyde Park but contained a like amount of history and monuments throughout. Although I would be content spending a length of time in any London green space Regents and Kensington would be my top choices.

Theatre

Overall I enjoyed going to the theatre on so many occasions. What better place to do so than in London after all? Here I will discuss my favorite performances and theatre venues.

All in all I enjoyed all but two of the performances we saw. The two Shakespeare productions at The Globe Theatre were fantastic. Although I did not particularly enjoy reading Troilus and Cressida it made a huge difference to be there so close to the actors. The fantastic drum chorus at the end really sealed the deal. As You Like It was probably my favorite show I saw here in London. Although it is one of Shakespeare’s simpler plays the actors really made it jump off the page. Being down it the pit was fantastic because of all the ad-libbing and constant interaction with the crowd. I even felt traces of Touchstone’s saliva on my arm at one point.

The other Shakespeare performance I saw, All’s Well That Ends Well, was lackluster. Although the Olivier was my favorite performing venue (this is what an auditorium style theatre should be like…why can’t Dickinson have something like this?) the play itself was odd and ended on an abrupt and odd note.

The other play we saw at the National Theatre, The Pitmen Painters, was fantastic. Although I was dozing a bit because of the Benadryl I took right before the show, the actors kept my attention and I appreciated that the play was based off of a true story.

Easily the oddest play we saw was Arcadia. An extremely intelligent performance the play juxtaposed two different periods in time and created a singular storyline in which the plot was based. Overall it was an entertaining performance that made me think early and often.

Finally there was Blood Brothers. The lone musical I saw produced feelings of disbelief, anguish and held back laughter. The ridiculous 80’s sound track and creepy narrator just didn’t do it for me. I think it’s safe to say that I was not the only one from Humanities 309 who was a bit surprised to see just about everyone in the audience give it a standing ovation.

I had a very positive experience with the theatre here. I would go back to the globe again and again. I loved being that close to the action. I would also enjoy seeing another show in the Olivier. There really is so much to choose from here. It’s simply a matter of figuring out your tastes and saving your money so you can see a lot of performances.

Churches

From Westminster Abbey to St. Paul’s Cathedral we saw most of the major churches/cathedrals during our month in London. St. Paul’s was easily my favorite. From the fantastic crypt to the hundreds of stairs up to the tower it had so much to offer in the way of history and mystique. Westminster Abbey fascinated me primarily because of all the literary figures that had been buried inside as well as the room that was dedicated to “The Order of the Bath”. Other churches that I really enjoyed taking a look at were: “St. Martin in the Fields” which sits just outside Trafalgar Square and Nicholas Hawkesmoore’s “Christ’s Church” which is located in very close proximity to Brick Lane.

Other Religious Institutions

Overall the Sikh Gurdwara was my favorite place that we visited. I appreciated the simplicity of the religious doctrine as well as the conviction and honesty with which our tour guide, Mr. Singh spoke. The morning was capped off with a fantastic sit down meal together in which everyone was served the same food and drink.

I had different feelings about the Hindu Mandir. It was clear to me from the very beginning that the Hindu religion is not nearly as modest as Sikhism nor are they trying to be. From the extremely decorative prayer room, to the museum located right in the center of the Mandir I never felt particularly comfortable inside.

The only religious institution I wish we had gotten a chance to visit is a Mosque. I had been to one many years ago but I did not remember a whole lot from my experience. I wonder how much more lively the East End, and all parts of London would be if Ramadan were not taking place during our time here.

Museums

I could go on and on about museums so I will attempt to stay as concise as possible.

The British Museum was massive, convenient since it was so close to the Arran House but a little one dimensional at times. One of my favorite exhibits at the British Museum was a special exhibit on Living and Dying that drew information from all different time periods and cultures.

The National Gallery was fantastic. Although I have a hard time appreciating some visual art the gallery kept my attention for a number of hours. Seeing so many famous works of art was phenomenal.

The Tate Modern was my least favorite museum here. Although I am trying I have a hard time understanding modern art. After about 45 minutes in this museum it ended up being too much for me.

The Cabinet War Rooms/Churchill Museum were two of my favorites. The realization that I was standing in one of the most important places in World War II history was unbelievable. The War Rooms felt so authentic. I really felt as though I had been taken back in time to the 1940’s while inside.

The Victoria and Albert was easily my favorite museum in London. There was so much variety inside and so much to see. I could have easily spent a few days inside. Two of my favorite exhibits were the silver and jewelry exhibits. I’m not sure what this says about me as a person but I found it unbelievable that individuals could even own such treasures. I also enjoyed the laid back atmosphere of the V&A staff. At most of the other museums I visited I felt like I was doing them a disservice simply by being there. Although I understand that taking pictures of an object in a museum doesn’t do it justice I like to be able to have the option of doing so.

The Sir John Soane museum interested me but it wasn’t really my cup of tea in the end. It also had a stuffy atmosphere to it that I didn’t really appreciate.

One thing I can draw from my experience at museums here is that each and every one has something that distinguishes it. With so many museums I thought that it would be impossible to avoid some overlap but I never really felt that. Cheers to London and its museums.

Pubs

Finally we have pubs. What would London be without it’s public houses? In some cases pubs are the true museums of London, designating what an area was like in the past and what type of clientele it attracted. During my month here I had a chance to visit a few pubs and get a general sense of what some possible differences could be. It is clear to me that each pub brings something different and unique to the table. The Marlborough Arms was convenient being so close to the Arran House and was a great place to enjoy a pint over a meal with friends. The Court was conducive to socializing in a different way. The music was louder, the people louder and the drinks cheaper. Other places I visited offered other things that made them stand out as well. One thing that i’ve learned about pubs is that it’s hard for one to please everyone. Since everyone has different tastes and desires when it comes to pubs you are better off going to one with a small cohesive group.

To conclude this novel I would just like to say that I think we saw a lot of different faces of London this month. I realize there is much more to see here but between walking tours throughout the city, trips to major monuments and museums and individual exploration I have learned a ton about London, it’s history and where it is going. I look forward to more London explorations in the future but for now, ON TO NORWICH!

Tags: Churches and Cathedrals · Henry · Pubs · Theatre

September 14th, 2009 · 3 Comments

After all of this time spent in museums in London, especially the British Museum, I find myself asking just one question: How are they still allowed to keep this kind of stuff? I mean, I can’t exactly speak for the Greek government, but I imagine that they would want the sculptures taken from likely the most important structure in Ancient Greek history back. Oh wait, Yes I Can. Despite the fact that England’s age of Imperialism is most certainly gone and past, it is peculiar and almost funny to see that certain citizens of Britain are still holding to the imperialist mentality decades after their actual country gave it up.

In 1801, the Earl of Elgin decided that in order to prevent pieces of the Parthenon from being burned to obtain lime, he was going to excavate pieces of the temple and its sculptures to put under his protection. The only problem is that in order to protect them, he took them out of the country and sold them to the British Museum. Masked under the cause of protecting cultural artifacts, it is apparent today that it was nothing more than a trophy to liberate from Greece and its people. In fact today the term elginism means the practice of plundering artifacts from their original setting. So why is it that despite Greece’s continuous calling for the return of these artifacts that are rightfully theirs, England seems reluctant to give them up?

The answer seems to lie with everyone’s favorite blog topic: identity. There are some opinions that state that as a center of world heritage, Parthenon sculptures are better off in the British Museum that in the actual Parthenon. This probably would have been a valid argument at around the time that the marbles were actually stolen, but is laughable today. Playing the role of cultural center of the world, British supporters insinuate that Greece is in some sort of corner of the planet that doesn’t see anyone other than its inhabitants. This is the 21st century. There are few people who live in Europe who cannot in a moment’s notice hop on a plane and be in Greece within a 24 hour period. The truth behind the matter is that there are those in Britain (mostly likely A.N. Wilson is one of them) that yearn for the time that their country moved and shook the very foundations of the planet with its actions, enabling to go into countries and plunder what they pleased. Instead, they live in a country whose capital city is kept afloat by the tourist dollars of the very people that they ruled not a few hundred years ago. Whether legal at the time or not, it is long overdue for the marbles to be returned and for some individuals to live in the present, regardless of whether they work in museums.

Tags: Paul

September 14th, 2009 · 1 Comment

Today Sarah and Alli ventured into the Cabinet War Rooms and the Churchill Museum. From remarks from our classmates, we thought it would be a quick trip through, but it most certainly was not! The museum was packed full of video footage, interactive exhibits, artifacts, and sheer information. For us to fully read and thoroughly explore the place, it probably would have taken us about 3 hours. Since it was the most interactive and technology-based of all the museums we had gone to in London, we would like to further discuss the use of these ideas.

Both of us have worked with museums and exhibits this summer, so neither of us can help it but to look at exhibits with a more critical eye. The Churchill Museum, only just recently opened in February 2005, relies on its “cutting-edge technology and multimedia displays” to bring Churchill’s story to life. The displays include a 15 metre-long interactive lifeline that, by sliding your fingertips along a strip, you can access information from every year of Churchill’s life.We felt the most effective interactive display was a touch-screen poll that initally asked the guest’s opinion on a certain aspect of Churchill’s life, such as “Do you think Churchill was a good wartime leader?” You were then offered more information on your topic and then reasked the question to see if your opinion changed.

We then thought about the importance of technology in museums and what it has added to the visitor experience. Technology has improved museum exhibitions in many ways: visitors can access historical documents, watch video footage, play “educational games” to learn information, and the museum is able to house much more materials through databases than they could before. It also allows visitors to choose whether they would like to view more information or “do research” or they can decide to move on. In this way, the experience is much more “tailor-made” for the visitor, allowing them to explore their own interests.T

The use of technology comes at a price. First of all, many museums do not even have the funding to afford such displays set up, even though it would benefit them greatly. Many museums, whether they are being rennovated or newly opened, are almost expected to have some sort of technology involved. Also, as we all know too well, the use of technology often comes with glitches and is susceptible to malfunctioning. The 15 metre interactive timeline was a great idea, but we could not really figure out how to use it! For two 20 year-olds who grew up using technology, we can’t even imagine older folks trying to figure out some of these displays.

Overall the technology benefitted our experiences in the Churchill Museum. We noticed most of the visitors engaged with the interactive media and we learned a whole lot more than we expected to. However, museums need to carefully evaluate their reliance on technology-based exhibits. The ideal exhibit would be a balance of both the traditional artifact-based model with some elements of technology to enhance the objects and the concepts presented.

Tags: Alli · Sarah