September 20th, 2010 · No Comments

Many of us have already talked ad nauseam about the rules governing Tube behaviour. No eye contact. All extremities and personal belongings to yourself. Never strike up a conversation with your fellow passengers (unless it is to moan about a delay or some noisome activity going on in a station).

However, we have also observed many exceptions to these rules, mostly in the form of young couples and Public Displays of Affection in varied locations and to varying degrees of intensity.

Beyond this, I have noticed that the LGBT community- particularly lesbian couples and cross-dressers/transgendered individuals- is extremely present here in London. As a group, they seem much more open and accepted here in London than some of the other cities I have been in. What the cause is, I don’t know- perhaps it has to do with the laws (I believe gay marriage is legal in England)? As someone who has and has had LGBT friends, I heartily applaud the apparent acceptance the community enjoys here.

[From one of the LGBT London support sites: http://www.pinknews.co.uk/images/kulgbt.jpg]

[From one of the LGBT London support sites: http://www.pinknews.co.uk/images/kulgbt.jpg]

Anyway, as I was making my way back to the Arran House one day, I had an encounter with a lesbian couple that broke almost all the English rules of behaviour (not THAT kind of encounter . . . don’t get too excited, gentlemen)

I was transferring from one line to another and noticed two women in front of me holding hands and I remember thinking to myself “Awww, how sweet. I wonder if they’re sisters? Or . . . are they a couple?” While the TV show The L Word may be set in Los Angeles, I have not seen many gay couples – particularly lesbians- who feel comfortable enough to openly express affection in public.

We ended up in the same Tube car and the only open seat happened to be next to one of them. The other, a heavier woman, sat opposite and, within seconds of the doors closing had started fighting with the teenage girl sitting next to her (who, interestingly, looked and sounded to be foreign, not White-British). I quickly assessed the situation: both women were black, but the heavier one (who clearly was the femme in the relationship) was strongly taking on the Angry Black Woman persona while her partner (who was very butch) didn’t interfere except to say, “Do you have a problem with my girlfriend?” The butch lesbian was the one sitting next to me, so I turned to her girlfriend sitting across from me and asked if she wanted to switch seats with me so they could sit together. She seemed very surprised and pleased that I had offered but declined- I think she wanted to make the person sitting next to her uncomfortable for a little while longer (she said as much herself) and then leaned over and kissed her girlfriend next to me. As she continued arguing with her neighbour and generally drawing attention to herself, her girlfriend sitting next to me struck up a conversation, asking where I was from. As it turns out, she had visited the States once and stayed not 10 minutes from where I grew up! When the train got to their stop, both women took hands (the heavier one glaring daggers at her antagonist- frankly, I couldn’t decipher what the cause of contention was but it sounded like the issue had arisen from the woman’s size – maybe taking up too much seat room? – her race or her obvious sexual orientation) wished me a pleasant stay in England and departed.

After they got off the Tube, the girl who had been fighting with the heavier woman glanced at me suspiciously and then looked away. I’m still not certain what my crime was, that I was talking to people on the Tube at all, that those people were lesbians, or that they were black. Perhaps a combination of all three.

Since that incident, I have seen several more obviously-lesbian couples and some obviously-cross dressing or transgendered men walking around on the streets. From what I have observed and experienced, it seems to me that the gay community here is much more open, much more free about expressing affection and- as I experienced on the Tube- much more willing to break with the established rules of English social behaviour. And yet, the irony is there were still the restraints of other behavioural roles – the gay persona as well as the racial persona- coming into play. Perhaps the moral is that all people – English, American, black, white, gay, straight, whatever – are always adhering to some expected social code. We can reject some and embrace others but one is always present and guiding our public behaviour.

As a dedicated people watcher, I found this whole experience and the attention it made me pay to individual couples just fascinating. I tried very hard in my relation of it to use as netural and widely accepted terms as possible, hoping to cause no offense to anyone on any account.

Tags: 2010 Elizabeth

September 11th, 2010 · 2 Comments

While visiting the British Museum several nights ago, I noticed an interesting behavior exhibited by different ethnic groups, depending on the culture focused on in a given room. The exhibits that I was looking at that particular evening (Ancient Greeks and Ancient Asians) were rather diverse, and it was precisely this diversity that alerted me to this phenomenon. While wandering through room after room of Greek artifacts, I noticed that Asian visitors (with only very few exceptions) would pass through these rooms without stopping to actually look at many, if any, of the artifacts. I slowed my pace considerably through the remainder of the exhibit, to observe the most number of people, and sure enough, Asian visitor after Asian visitor passed through the rooms, only occasionally stopping to look at one artifact, or more likely, take a picture, before moving on. Compared to visitors who looked to be of European/American ancestry, the difference is stark. These people generally took their time through the exhibits, stopping to gawk at an exceptional pot or other artifact, and generally going at a more suitable pace for such a wonderful museum (in my opinion).

Intrigued by this, I moved on to the Asian exhibits to see if I could find a similar trend there. Sure enough, I did, but it was almost completely reversed. In this case, the Asian visitors were the ones that were slowing down to look at everything, while the people that were zipping through were almost entirely Caucasian. This is exactly what I expected to find, as my hypothesis prior to entering the Asian room was that people, whether consciously or subconsciously, care more about cultures closest to their own, and are therefore more interested in the history of these cultures. This is why those of Euro-American heritage took their time through the Greek exhibits, but zoomed through the Asian room, while the Asians exhibited the opposite behaviour.

All this may either be evidence for or against the British Museum. This small, unscientific experiment of sorts seems to show that people don’t care about other cultures, at least not as much as their own. It’s very easy to extrapolate this to all sorts of things (for example, various imperialist wars in the Middle East, religious intolerance all over the world, etc.), but I don’t want to make this post too upsetting, so I won’t dwell on sad things, and get back to the Museum. I’d rather think that this phenomenon shows that the Museum has something for everyone. No matter where you’re from, you’ll find a piece of our history at the British Museum. I’d like to think there’s a bit of hope left in the world, so I thoroughly believe that this latter theory more true than its predecessor.

Interestingly, to finish things off, I travelled to the Americas section of the museum to see what kind of demographics it attracted, to compare to my observations in the Greek and Asian sections. I found that no one, no matter who they were or what they looked like, just buzzed through. Everyone was transfixed by the Native American headdresses and canoes, but I found no Americans in the exhibit (It’s surprising how easy we are to pick out, once you live in another culture for a while). This seemed exactly contrary to my other findings, as going off of my findings, you would expect to see a whole gaggle of Americans in the part of the museum dedicated to their history. On closer inspection however, this makes perfect sense. The vast majority of Americans are not of any measurable Native American descent. Instead, we’re predominantly from Europe and Asia, which incidentally are the exhibits in which I found all the “missing” American visitors. This “exception” seems to in fact further prove the rule, as Americans, as part of a “melting pot,” still associate closely with the history of their international forefathers.

Tags: 2010 MatthewM · Museums

September 3rd, 2010 · 1 Comment

First, who’s not in the National Portrait Gallery? Minorities! Honestly, even without the prompt, it would have been a slow realization that as we walked through room after room of white faces, something was missing. There was one freed slave portrayed in the audience of an abolitionist convention, and that was about it as far as paintings of minorities at the Gallery go.

Second, and more broadly, working class people are not in there. This, to me, is less upsetting as it’s just a natural consequence of the fact that only the upper crust can afford to have portraits commissioned. Hours after visiting the Gallery, though, the lack of minorities still rankles, for one simple reason. If a black or Asian or Latino family came to visit the Gallery, and one of the children asked their parents “Why don’t any of these people look like us?” the parents would have no good answer.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

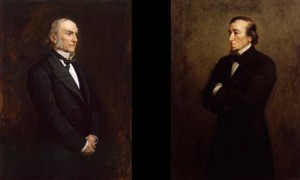

We were supposed to pick one portrait that we found particularly affecting. As a political science major who has taken British History 244, though, I could not resist going with the dueling portraits of William Ewart Gladstone and Benjamin Disraeli. Gladstone was the pillar of 19th century liberalism, while Disraeli was his counterpart on the right.

credit: youreader.com

This is exactly how the two portraits (by the same artist, Sir John Everett Millais) appear in the Gallery. In the Victorian era, the two were the titans of Parliament, serving as Prime Minister six times collectively. There is much, much more on their epic personal and political rivalry here:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/disraeli_gladstone_01.shtml

A favorite quote of mine on their lack of mutual respect, from Disraeli is “The difference between a misfortune and a calamity is this: If Gladstone fell into the Thames, it would be a misfortune. But if someone dragged him out again, that would be a calamity.”

Their respective portraits contain subtle and not so subtle bits of political imagery. First, Gladstone is facing to his left, while Disraeli is facing his right. The rest of what follows may be a bit of armchair psychology, but I believe it speaks volumes about both men.

– Gladstone has his hands folded, while Disraeli’s arms are folded in an aggressive posture. Disraeli was far more warlike as prime minister.

– Gladstone is looking towards the sky, while Disraeli’s gaze is a bit more earthward. This is in line with both men’s fundamental outlooks on life: Gladstone considered himself a great Christian moralist, while Disraeli preferred to concern himself with more earthly issues, considering Gladstone to be out of touch with the nitty-gritty of the world.

While the placing of these two portraits together obviously has an intended effect, that does not make the effect any less powerful. While standing in front of the two portraits, I felt like I could almost feel the hate flowing between these two great men, a great moment for a politics junkie like me.

Tags: 2010 Dennis · Museums

When discussing the sphinx of Taharqo at the British Museum, the Kushite king of Egypt, the narrator of A History of the World states that “it makes sense to keep using a language of control that everybody is accustom to accept.” This is in reference to the fact that during their reign in Egypt, the Kushites adopted Egyptian customs to appease the people they were controlling. In response, the Egyptians likewise attempted to absorb the Kushites into their own culture, “blandly calling the reign of the Kushite kings the 25th dynasty, thus quietly incorporating them into an unbroken story of an eternal Egypt.” It’s clear to me from this that naming something, the smallest thing – the ethnicity of an emperor, the description of a statue, the favorite food of a people – is away to secure power. Speakers in history will always maintain their superiority.

These strategic cultural “inclusions” smack of what Tarquin Hall points out of imperialism in Salaam: Brick Lane when Aktar states in frustration “you people are quite capable of making absolutely anything English if you choose to do so” (247). Imperial nations absorb parts of a culture they conquer to please the people, water it down, and spit it back out as only barely recognizable, a part of the empire. This is what I sense other people worried of Afro-Carribbean culture in their analyses of the Nottinghill Carnival, and possibly with good reason. What was once a celebration of culture could easily become a sort of spectacle for dominant groups. Maybe people come to the carnival to party rather than celebrate a culture. Maybe they come looking for something “authentic” and tokenize Afro-Caribbean culture rather than really respecting it.

I’ve been seeing this pattern all over England. There are curry shops everywhere. I’ve had more opportunity to buy it that than fish and chips. I keep seeing women on the Tube in head coverings, but otherwise wearing Western clothing, and I have to wonder if England and it’s vestiges of imperial culture are somehow swallowing other cultures as well. I see mixed race couples, and wonder what they call themselves since hybrid identities like Asian-American don’t really seem to exist in Britain the way they do back home.

I have always been taught that assimilation is a tool for silencing so marginalized groups can’t write their own history. In the United States, when someone tells you to speak English, straighten your hair, and embrace the American Dream, it really means your people are ugly and unimportant; pretend to belong and maybe we will tolerate you. But at the same time, the absorption of different cultures in England really could be a compromise. I haven’t heard any racial slurs yet. The fact that there is so much diversity and interracial mingling without conflict suggests that people don’t feel marginalized. Rather being coerced or having their customs forcibly erased, maybe new immigrant English consciously choose to adopt some dominant customs as a way to gain acceptance Maybe assimilation in this case is really the kind of cultural sharing that a society needs to operate peacefully. But my American instincts are still tell me to run before I start saying sorry every 5 seconds and can’t talk about money.

Tags: 2010 Jesse · Uncategorized

September 12th, 2009 · No Comments

This post is in response to the excerpt that Professor Qualls shared with us from his upcoming book. In this introductory chapter, he raises several key points which translate into our discussions about race, ethnicity and identification in London.

First, he uses the term “identification” rather than “identity.” I feel that this terminology is much more appropriate – even somehow liberating – in that it implies a choice and agency whereas the term “identity” connotes a sense of inescapability.

Second, Professor Qualls claims that “[a]s with memory, urban identifications are both internally and externally manufactured.” This can be seen in London, especially. The language barrier and cultural difference that immigrants inevitably experience coming to a foreign country certainly play a role in this “process of identification.” It is reasonable that immigrant communities would identify much more readily with a community that theirs their cultural, religious and linguistic traditions. It is the external forces, then, that cause problems.

Indeed, Qualls mentions that “[i]dentification can be either categorical or relational.” When outsiders (external forces) categorize or imagine relationships between immigrant groups where none might exist at all*, they are essentially “othering” those populations, isolating them from the rest of society and making it virtually impossible for any foreigner to feel comfortable here, let alone the possibility of “assimilation” – which I think is a completely ethnocentric idea to begin with.

It is not the responsibility of immigrant populations to adapt to the country in which they are residing, so long as they learn to respect that country. But this is a two-way-street. Locals must also learn to respect those immigrant populations which whom they share their space.

Particularly in London, these unique immigrant communities are what makes the city uniquely “London.” Or, to, yet again, quote Qualls: “maintaining past traditions was essential to the stability and happiness of the population, which in turn would reflect well on the central regime.”

*Some of you may remember the story Andrew Fitzgerald, Andrew Barron and I shared with you at the beginning of the course: At our market in Elephant and Castle, we witnessed an altercation between a darker-skinned customer and a white, cockney fruit and veg vendor. The vendor called the customer a “Paki” and obviously had no legitimate basis for determining this man’s ethnicity. Just because the customer had darker skin, the cockney vendor “related” him to a Pakistani. This is a dangerous comparison which only serves to fuel racism.

Tags: Anya

[From one of the LGBT London support sites: http://www.pinknews.co.uk/images/kulgbt.jpg]

[From one of the LGBT London support sites: http://www.pinknews.co.uk/images/kulgbt.jpg]