September 21st, 2010 · No Comments

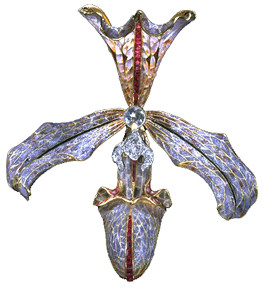

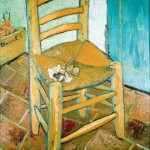

The way I feel about England’s museums (BM in particular) is the same way I feel about Tom Brady. They are both morally flawed, but too beautiful for me to honestly give a damn. So in that spirit lets forget about the mistreatment of Greece and Bridget Moynihan and just admire the physical beauty and inherent cultural value of the objects themselves. Sure, the jewelry collection in the Victoria and Albert represents the opulence, indulgence, and filthy wealth of the upper classes and royalty, but look how sparkly those diamonds are! The intricate cloisonne! The colorful enamel! The gemstones! Don’t hate the tiara because a spoiled rich woman owned it, admire it for its elegant design and exquisite craftsmanship.

Hair ornament in the form of an orchid, made by Philippe Wolfers, Belgium, 1905-7. Museum no. M.11-1962. Image from the Victoria and Albert Museum website

I also must say, setting aside moral issues and countrys’ bruised egos, what is truly in the best interest of the objects themselves is for them to be left alone. Art and artifacts should be handled and moved as little as possible to avoid damage and the acceleration of deterioration. Professor Earenfight, who curates the Trout Gallery and teaches the museum studies course at Dickinson, likes to say that art and artifacts are like the elderly. They are set in their ways, used to their specific atmosphere, and the best thing for them is to disrupt their comfort as little as possible. The bottom line is, virtually all of the objects in London’s museums are priceless and definitely irreplaceable. The transportation of any of these objects across countries and continents is absolutely horrifying from an art conservation/curatorial point of view.

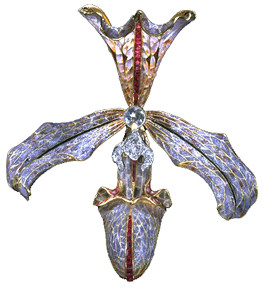

In any case, how great is it that we can get into all of these places for free? Sure, government subsidization lends itself to government censorship, but the fact that I can just wander in off the street, as I am, and walk right up to Jan van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait, or Joseph Wright’s An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, or the ship burial treasure from Sutton Hoo, or the Rosetta Stone and countless other treasures more than outweighs any negative aspects for me. London’s collections are among the finest in the world, and they are open to everyone. Now that’s beautiful.

Tags: 2010 Rachel

September 21st, 2010 · No Comments

The Brits pour money into their precious museums, further proof to my idea that the Brits hold their rich and storied history above all things in this fine country. The Museum of London is probably the best example; a simply laid out but large museum with easy access to the public and several treasured pieces of London history contained within its walls. Like the Museum of London, most museums are easily accessible and a majority of them are free to the public, however it seems like the museums they offer are catered to a good balance of Brits and tourists alike. While walking through a museum like the British Museum or the National Portrait Gallery, it is common to hear a slew of accents from every corner of the room. Italian, spanish, english, you name it, these people are in the museums. Of course this kind of museum experience can only come from the British government pouring tons of money into these places, making them into a piece of history themselves.

The history on display in the museums isn’t only that of the Brits, however. I am sure it took millions upon millions of dollars to acquire the historical objects contained in museums like the British museum. Perhaps this is a testament to not only the Brits appreciation of their own history, but also of the history of the world. London is without a doubt, one of the most international cities in the world. Tourists come from all over to see the sights and people from all corners of the globes live tucked away in various corners of London. All these points lead me to believe that Londoners also take great pride in acknowledging how they themselves are linked to international history and will pay big bucks for precious artifacts to be moved to their museums.

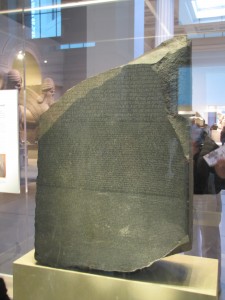

The museums themselves seem to operate like any other public establishment in the city of London. The feeling of being pushed around from queue to queue is ever present, even in a place like a museum. The result is that you kind of have to rush yourself from museums, or as a fellow classmate said in their blog recently you have to learn to “skim” museums. It took me ten minutes just to get a good view of the Rosetta Stone because of all the people crowding around, and everyone seems to have you on a two minute timer to have your look and then move on. Even in a place like the National Portrait Gallery, I got the feeling that if I spent too much time looking at a painting or sitting on a couch (the green leather was incredible) I was going to be the recipient of dirty looks from every direction. Despite being invisibly queued up in most sections of museums, there is usually enough to experience for you to get lost for days.

Overall, the museums are definitely a great aspect of London and I believe that the fact that they are subsidized is a very good thing. It keeps tourists coming and it keeps the English aware and proud of their history and their knowledge of others’. The museums of London helped me to appreciate (like a good Londoner) the value of a trip down history lane.

Tags: 2010 Benjamin

September 11th, 2010 · 2 Comments

London’s diverse museums all have an element of British imperialism. The three which best show this are the Wallace Collection, the Sir John Soane Museum, and the British Museum. Yet, each takes a different approach to them: the British Museum is the standard artefact with didactic label, the Soane shows the spoils of an imperialistic age in the wonderful cabinet of curiosities method, and the Wallace Collection arranges its collection as a wonderful combination of the two.

The Rosetta Stone, which has been a centerpiece of the Egyptian repatriation demands.

We’ll start with the British Museum. Perhaps the most controversial collection because of the Elgin Marbles, most of the collection could probably be at the center of a repatriation argument if a government decided to challenge the museum. Instead of noticing that the museum was a shrine to British imperialism, my first thoughts (once I pulled myself away from the medieval galleries) were about the museum’s role in the ongoing battle over countries reclaiming their artefacts. My general beliefs on repatriation are simple: the works belong wherever they are going to get the best care, which, unfortunately for the vast majority of the ancient objects, is not in their countries of origin. For example, there is no way that Egypt can assume responsibility for its antiquities; the ones there are deteriorating alarmingly. While Hawass has done a good deal for Egyptian antiquities, their facilities still are nowhere near those of the British Museum’s facilities. Furthermore, shouldn’t objects that have influenced the whole of history be where the most people have access to them? Surely that is here, in London, not in Cairo?

One of the Elgin Marbles

Unfortunately, that argument is no longer valid for the Elgin Marbles (although, while not as an unpredictable environment as Egypt, Greece does have its problems which could threaten the marbles). Greece has a new acropolis museum that is a perfectly suitable house for the marbles. So, why do I still believe they belong in London? Aside from the whole no-objects-can-leave-England-law and the incredible galleries they are currently housed in, there a couple of reasons. Firstly, their provenance, unlike that of the Italian krater the Met repatriated to Italy, shows them to have been purchased legally versus outrightly stolen. We may not agree with the way they were handled in the 19th century, but because we have a different understanding of the proper way artworks should be sold/purchased does not mean we can go back and make amends with everything. The world’s great museums would be emptied. Secondly, where they are now, they are more accessible. If Greece didn’t have almost as many as the BM, I’m sure everyone would feel differently about the issue. (Well, except for Greece, which would still demand them all, even in the BM only had one.) Because repatriation has become such an important issue, I do believe that even if English law did not forbid it, the marbles would never go back to Greece because once the BM accepts Greece’s arguments, the watershed for repatriation will be open and museums will be scrambling to quadruple check their works’ provenances, possibly wasting valuable resources.

It was only after my second visit to the British Museum that I wondered about some of the works’ provenances. However, from the moment I stepped into the Sir John Soane, all I wanted to do was demand to see some of the provenances of various works, as well as pick up the objects to examine them and the way that they were removed from their original locations. I think part of the reason that it took a second visit to the BM to question it was as one of the leading museums in the world, it has more authority as the stellar, but smaller, Soane. The traditional layout of the BM commands respect, whereas the Soane is easy to mistake for a pile of junk haphazardly arranged. Except, it is the exact opposite: the Soane has incredible pieces. (I could have died of joy looking at the random Gothic bits.) Because of the arrangement- a life size cabinet of curiosities- it is easy to forget that all of the works can point to the achievements of Soane and his time, noticeably imperialism. When walking through, one’s mind is trying to take in everything and is not assisted by didactics, the larger picture is sometimes lost, unlike at the BM, where the layout and didactics remind you almost constantly that while the museum is “British”, the majority of the collection is not. Furthermore, the Soane’s arrangement allows one to feel closer to the objects. Indeed, it is easy to get away with a close examination of the work on the wall and touching them. In the BM, the viewer is often annoyingly separated from the work by class or a rope barrier.

If the BM is arguably the most controversial museum because of its collection, then the Soane is the most overlooked for controversy. Lots of the works were supposedly removed from crumbling sites. Were the sites crumbling before or after the works were removed? Did the dealers have explicit permission? These questions are largely overlooked; in fact, lots of information is overlooked, which adds to the feel of a cabinet of curiosity.

The Wallace Collection

The Wallace Collection is like the Soane in that it started as one cohesive collection and has grown, as well as that it shows the way the works were staged by their original collector. However, unlike at the Soane, the Wallace Collection does an amazing job of showing lots of works in a way that is not as overwhelming. The collection is mostly housed in period rooms, which add to the atmosphere of the museum, greatly enhancing the works. Instead of wondering about whether the objects should be repatriated, the collection sets up the works in such a way that the viewer is not distracted by theoretical questions on museum practices. (Unless said viewer gets bored of Rococo and armour.) Furthermore, the collection focuses on European art, which focuses it a bit more than the other two museums. If anyone is interested in armour, the Wallace’s collection is superb and world-renowned. Instead of wandering around the museum pointing to works I wanted to examine for causes to repatriate, I wandered the Wallace wondering why certain works were hung together and why anyone would want rooms upon rooms of Rococo art, much less why I was wondering around them when there were three outstanding armouries downstairs that were calling me.

Yet, part of me wonders if Britain didn’t have it’s imperial past, would I be able to see this quality of art and artefacts. If I were able to, would I wonder about the provenance and history of each work as much?

Tags: 2010 Stephenie · Museums

September 11th, 2010 · 1 Comment

Throughout our time here so far, I’ve been to museums that I’ve loved and loathed. Regardless of how I felt about the collections, each museum seemed to say something about England, as well as demonstrate amazing educational programs. (I’ve decided to tackle the issue of museums in two separate blogs. I’m not going to deal with repatriation and provenance, both issues have been on my mind a good deal at a couple of the museums, most noticeably the British Museum and the Sir John Soane museum, in a second blog. This one will be more general and focus a bit on educational programming within the galleries.)

Firstly, thinking back to over two weeks ago, the Greenwich Observatory was an interesting museum. It wasn’t one of my favourites, partly because of the collection, most of which I did not really care for. However, the excellent interactive bits throughout the exhibits were engaging. It did a good job explaining the importance of Greenwich time and it’s relationship to the development of shipping. (I probably know more about longitude now than I ever needed to know.) Unlike the other museums I’ve visited, the achievements it highlighted, were an integral part of the build-up to imperialism vs the spoils of imperialism.

Prime Meridian

The Tate Modern would be my next least favourite. I like some modern art, but it is not normally my first choice to spend an afternoon admiring. (Unless it is a Kandinsky show.) Throughout the Tate, I felt that some of the space had been wasted, especially on the floor where the membership room was located. The main galleries were nice, but offered very little in terms of supplemental didactic materials that could further engage the viewer- all of that was outside of the gallery. While the interactive bits were very interesting, they could easily distract from the art itself. (The seemingly endless reel of video shorts seemed to confirm this.) Yet, I admired the activities for the younger children which engaged them and put the art on their level. By separating the modern art from its other collections, the Tate seems to promote its standing: it is worth more than a gallery add-on in the main building.

The Tate Modern

The Guildhall Art Gallery, by comparison, offered very little interactive displays. By the time I had visited here, I was so use to in-depth descriptions, a wide audience, crowded galleries, and fun didactics, that the seemingly empty gallery caught me off guard. It was nice to see the Roman Amphitheater; the room’s set-up was incredible with recreations of the gladiators. However, the gallery’s art collection was lacking. It mostly seemed to be lesser works of second-tier artists or smaller copies of major artworks created later in an artist’s career. I believe that the gallery was trying to show the positives of British art in the last 200 years, but the gallery failed in this mission because it failed to hold one’s attention for long. Furthermore, the special exhibitions were too text panel heavy. (Balance seems to haunt this gallery.) The panels were informative, but when 3/4 of a panel is devoted to reproducing a picture which is hanging next to the panel, there is a problem. The viewer is drawn to the reproduction, not the actual artwork, defeating the point of the gallery.

The National Gallery is one of my favourites that I have visited, partly because of the Wilton Diptych and partly because there is one spot where my favourite Holbein and a Vermeer are both in one’s line of sight. The collection is outstanding and the works seem to represent the majority of art history. Well, my favourite bits at the very least. While there are not as many interactive activities, the didactics are engaging and there are educational options available. Instead of only seeming to be the spoils of imperialism, the collection has a truly British feel, partly because so many of the works are ones that directly relate to English history rather than the history of far off places. Furthermore, it’s easily accessible and not hidden like the NPG; it’s prominent position on Trafalgar Square also helps with accessibility.

The Wilton Diptych

(For more information: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/english-or-french-the-wilton-diptych)

The Victoria & Albert would be tied for my second favourite museum thus far with the National Gallery and the British Museum (which I’ll discuss in my other museum post). I spent almost 2.5 hours in the new Medieval and Renaissance Galleries, which were not only gorgeous, but held some incredible pieces. (Can I please just have one grotesque figure?! Just one…) Several people have noted that the sheer amount of stuff in the museum is overwhelming. Outside of the M&R Galleries, I would agree with this. Here, the museum seemed to be addressing this issue, trying to open up the galleries and spread out some of the pieces. Furthermore, the excellent listening stations found throughout the galleries were a perfect mix of in-depth and cursory information, allowing the viewer to pick and choose the information they heard based on their interests. (Highlight: listening to Gregorian chants while viewing the different altarpieces, all of which were stunning.) The V&A proudly displayed artworks which combined to tell the story of the world through art. Unlike the British Museum, it did not claim to be a solely British institution, which I think in some ways helped make the museum a more open place. Furthermore, because it is an artistic school as well, it’s collections are all educational, adding to a different responsibility for its didactics and what is should be collecting. It filled gaps through its amazing replicas gallery, which included some of the most famous works ever created.

Misericord, Victoria & Albert

When taken together, the museums not only provide one of the most stellar examples of museum education in practice, but also serve to tell the triumphs of the British Empire and to highlight the triumphs of the larger artistic international tradition. If London is a city of the world, then its museums reflect this.

Tags: 2010 Stephenie · Museums

September 19th, 2009 · 4 Comments

The Sir John Soane Museum was the last thing I was able to squeeze in before leaving for Norwich. The museum was interesting, however I do not think it was very educational. It was essentially just peering in on Sir John’s house and his collection, but there were very few signs telling the museumgoer about the relics that were scattered around the house. The architecture was amazing as was the collection, and like most of my classmates I would love to live there if it were not so narrow in parts of the house. However, I do not see its relevance to the course. Why Professor Qualls did you choose to throw it onto our list? I am having a hard time saying anything about the museum because I do not see how it fits into the theme for this class. Honestly, I have learned more from the museum’s website than I did in the actual museum. The website has the entire collection on it with blurbs about the history of each piece. However, unlike most other museums the website does not display a mission statement or any of the museums goals. I believe that every museum should have a mission statement. This makes helps the curators organize exhibits, artifacts, and information panels. With out a strong goal relics are just crammed together, like in the V&A, or there is very minimal educational material, like the Sir John Soane Museum.

I never thought of myself as particularly interested in museum studies, but after visiting all these museums I can see what foundations need to be there for a museum to work. Out of all the museums we visited I feel that the Docklands museum did the best job in presenting and preserving its artifacts and its history while doing a great job educating its visitors. The museum has a clear goal: to educate the public on the history of the docklands. It also has a clear pathway that one can choose to fallow at their own pace, while the British museum had no path way and tended to get very congested at various parts of the exhibits. These large crowds of people greatly affect the safety of the artifacts that the museum is trying to preserve. People should not be allowed to touch, feel, hug, and take pictures of ancient Egyptian sculptures. These crowds are also not good for the safety and education of the museumgoer. Old women or men should not have to be pushed around to have a glance at the mommies, and one should be able to easily see and read the information panels next to the relics if they choose to do so. At least The Sir John Soane museum limited the number of people in the museum at one time in order to protect the artifacts and the people (as it would probably be a fire hazard for too many people to crowd into that building). Maybe the British museum can look to the Soane museum for advice and limit the number of people in the mummy room at one time and increase security. While perhaps the Sir John Soane museum can fallow the British museum’s model and provide more information on the artifacts within the house.

Tags: Rebecca

September 14th, 2009 · 2 Comments

Yesterday I had a absolutely HORRIBLE experience at the British Museum.

It started off ok, as soon as I entered I got a map and began walking through some of the exhibits. I began my adventure in the Living and Dying Exhibit. I then began to climb up the stairs and headed into the Chinese Ceramics Exhibit. As someone who has practiced throwing pottery for seven years, I have a GREAT respect for ceramic technique and craftsmanship. However, I was not pleased with the woman who had answered her phone in the middle of the exhibit and was having a VERY loud discussion on her mobile. This irked me but what happened next sent me over the edge. After looking at the ceramics I went to the Mummy room. The room was packed with people and screaming children (not that I could blame them because I also felt like screaming). As I began to walk around the room in effort to see the mummies and read the panels next to them people, people were bumping me and pushing me out of the way to take touristy pictures with the sarcophagi. This completely disgusted me; these people have absolutely no respect for museums, the dead, history, nor their fellow museum goers. When my corpse is hundreds of years old I do not want it to be on display for people to take pictures with while they hold their thumbs high in the air. If I were those Egyptian pharaohs, commoners, etc. I would haunt those fools. By the time I left the room I felt as though I was going to have a panic attack: my heart was pounding, my head spinning, I could not focus on anything, and I was beginning to regret the coffee I had right before. The rest of the museum is a bit of a blur, I vaguely remember seeing people leaning on ancient statues. Most of the time I was at the museum I felt as though I was heading against the crowd. The only thing that I distinctly remember after that was almost getting run over by a large group of Asian tourists on my way out the door.

Something needs to be done to the layout and the security of these exhibits to improve the safety of visitors and of the artifacts the museum houses. Photography should not be permitted on the premises and a walking path should be constructed (especially in the Mummy room) to make it smoother and easier for every visitor to see and appreciate the artifacts. The use of mobiles in the museum should be restricted and enforced. There should also be more security protecting the statues and patrolling the area. I would not mind paying an entrance fee to the museum if it meant the museum would change these things.

Tags: Rebecca

September 14th, 2009 · 2 Comments

Here are two very different quotes/poems about the British Museum (especially the Reading Room)

“If an army of monkeys were strumming on typewriters, they might write all the books in the British Museum”

-Sir Arthur Eddington

| At the British Museum

-Richard Aldington

I turn the page and read:

“I dream of silent verses where the rhyme

Glides noiseless as an oar.”

The heavy musty air, the black desks,

The bent heads and the rustling noises

In the great dome

Vanish …

And

The sun hangs in the cobalt-blue sky,

The boat drifts over the lake shallows,

The fishes skim like umber shades through the undulating weeds,

The oleanders drop their rosy petals on the lawns,

And the swallows dive and swirl and whistle

About the cleft battlements of Can Grande’s castle…

I love the-wait for it- juxtaposition of these two quotes. One describes the beautiful “great dome” of the Reading Room and the other yields a sarcastic, even cynical, view of the very same room. I appreciate both for their differences, but I have to say that the British Museum is exceptional.

The sheer size of the building is enough to be completely overwhelming and the collection itself is staggering. When I first walked in and saw the Reading Room and the white floor and walls, I really felt the weight of the great minds of the past bearing down on me. At the time I had also been doing research on Virginia Woolf and George Eliot, two feminist literary figures in the 19th century. Both had studied in the Reading Room and had come up with some amazing pierces of literature there. For me, it bordered on a spiritual experience simply because I was in the presence of progressive thinkers who had so influenced the literary world.

And so that was my first impression of the British Museum and they didn’t stop there…I also began to formulate some questions about the past, present, and future of our own history.

Walking through the museum and looking at the relics and artifacts from ancient empires made me wonder what antiquities future generations will keep in museums from our lifetime. When does it become ok for museums to take bodies from, say, sarcophaguses and put them behind glass? When do our tools become tools of the past? I am still pretty astounded by exhibits and the sheer history that is encompassed in a single place. The funny thing about museums (and this one in particular) is that they paradoxically make these ancient civilizations visual, yet somehow less real. I think this is largely due to the fact that the pots, statues, and other relics sit within a huge and beautifully furnished building. They are simply displayed on stands, under lights, and behind glass. I feel more like I am peering through a window into another time rather than getting the sense that these artifacts were used by people as tools for everyday life. Overall, it was hard for me to marry the idea of ancient artifacts behind glass and it has given me something to think about as I continue to visit more museums while I’m in London.

Cabinet War Rooms

This particular blog will mostly be about how I felt as I walked through the war rooms which were pretty frightening

IDENTITY

Oxford v. Bath |

Tags: Maddie

September 13th, 2009 · 1 Comment

I had hoped that the Victoria and Albert would be something like the British Museum: large, but manageable. I was wrong. Entering the museum via underground tunnel, I was immediately confused as to where in the museum I was. Rather than the simplicity of rooms surrounding a central courtyard that all connected to each other, I was thrown into a maze of staircases, staff rooms, and an entire wing devoted to a cafe which took me several attempts to navigate around. By the end of my visit I was nearly too exhausted to make it back down the tunnel to the tube.

Don’t get me wrong, I did enjoy the museum. The fashion exhibit was, on entering, immediately next to me and it served as a good jumping off point, if not as amazing as I had been led to believe. However, a jaunt around the medieval section soon cheered me up quite a bit. The three story high room filled with plaster casts of ancient and gothic architecture made me particularly happy, especially the cast of Trajan’s column. I’ve studied this column, and I’ve seen pictures, but nothing is as amazing as standing next to it (despite the fact that it wasn’t the original). The sheer size and attention to detail made me dizzy. I had to consciously restrain myself from touching it. After drooling over it for a few minutes, I attempted to enter the other room of casts (in which was housed what looked like a cast of the Colossus of Rhodes), but was thwarted by scaffolding and a sign saying “observe from third floor balcony”. In my search for this mythical balcony I ascended some stairs and turned some corners and got lost. Very lost. So lost that I rounded a corner thinking “how will I ever get out of here and where the hell am I supposed to go next”. Luckily the gods seemed to hear me and deposited me in a safe haven for people like me: the Theater exhibit.

I loved the theatre exhibit, especially the dress-up box of costumes to try on (yes, I’m a geek, but what can I say, it was COOL!). The miniature set models were so well done, and the model of the Theatre Royale at Drury Lane almost sent me into convulsions. Its attention to detail was fabulous, from safety posters to the raked stage, to little men being raised through little trap doors. It gave a wonderful history of theater in London from about 1900 onward, and the exhibit was so interactive that I spent a good 45 minutes in it, and it’s really not that big. However, I eventually found my way out.

It then, however, took me another half an hour to find my way back to the subway. As much as I did enjoy the experience, the museum is trying to do too much at once. Instead of focusing on one type of exhibit or one time period or one country, it has crammed them all into a maze of rooms, leaving the visitor with the feeling of being beaten over the head with a textbook (albeit an interesting one) upon leaving. I think it would be a much more effective museum if it divided its exhibits up into different buildings. It has already separated the Childhood museum from the main one, so why not do it with more? They have enough exhibits in there to house hundreds of museums. Why cram it all into one?

Interestingly, I didn’t find the British Museum exhausting (or at least not as exhausting). Perhaps I find the way the rooms are organized more understandable, or the fact that most of it is linked to archaeology (or in the case of the Parthenon Marbles, stealing in the name of archaeology). The British Museum is not as large an amalgam of ideas as the V&A. The exhibits on ancient Rome and Greece, Assyria and Egypt, and even North America, they are all connected under the tent of archaeology and anthropology. The only problem I have with the museum is its questionable acquisition techniques (most of which have been pointed out to me by Professor Maggidis, so perhaps I am a little biased in favor of the Greeks).

However, I think the hodgepodge of artifacts in both these museums parallels the mishmash of cultures living in London brilliantly. The names “British Museum” and “Victoria and Albert” evoke very nationalistic images, but house such a variety of things, much like modern London. While neither museum specializes in Bangladeshi artifacts or Jewish culture, the fact that they do house so much of non-traditional English stuff shows just how diverse England would like to be. Its next step is to realize the abundance of cultures it already has, and perhaps show those off a bit too.

Tags: Campbell

September 7th, 2009 · 1 Comment

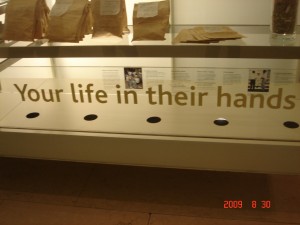

A description under Cradle to Grave by Pharmacopoei states:

“Cradle to Grave explores our approach to health in Britain today and addresses some of the ways that people deal with sickness and try to secure well being.”

It is an understatement when I say that I was surprised to see an exhibit titled “Living and Dying” which is located in Wellcome Trust Gallery in the British Museum. The gallery explores how people around the world deal with “the tough realities of life and death.” The exhibit further explores health challenges shared by many through out the world, and the ways that those individuals might deal with them based on their cultures, beliefs, and areas of residence. Creatively displaying visual representations of photography, quotes, documents, captions, and instillations the exhibit investigated people’s reliance on relationships in order to maintain their well-being. Exploration of people’s relationships with each other, the animal world, ancestors, land and sea for their well being are included.

As I walked down the stairs of the British Museum to the ground floor expecting to see the Aztecs (Mexicana) exhibition featuring tribal sculptures, history, and art instead I was greeted by Cradle to Grave. The central installation consists of two lengths of fabric illustrating the medical stories of a man and a woman. Created by Susie Freeman, who is a textile artist, David Critchley, a video artist, and Dr Liz Lee, a general practitioner, each piece contains over 14,000 drugs representing the estimated average prescribed to every person in Britain in their lifetime, tucked away in ‘pockets’ of knitted nylon filament. This specific piece explored the approach to health in Britain and the personal approach of the piece demonstrates that maintaining well-being is more complex than just treating illness. With 14,000 drugs, the artists included photographs and some treatments that two individuals have gone through. The common treatments for the man and a woman included an injection of vitamin K and immunisations, and both individuals have taken antibiotics and painkillers at various times. Other treatments were more specific such as for asthma and hay fever that the man suffered from when younger and quitting of smoking at seventy due to bad chest infection. The piece showed his death from a stroke at the age of seventy-six, “having taken as many pills in the last ten years of his life as in the first sixty-six.” The woman’s treatments included contraceptive pills and hormone replacement therapy. She was successfully treated for breast cancer. She is still alive at eighty-two although she does suffer from arthritis and diabetes.

Trying to figure out the purpose of the exhibit, I believe the artists are trying to explore the factor of living in the “modern” society and how treating an illness is not the only factor that needs to be taken into account. By representing two individuals, a male and a female, in the British society through photographs with their own captions written down, and objects such as contraceptive pills, a glass of wine, and needles allowed the viewers to relate in some way to the lives these characters have led and how it affected their health.

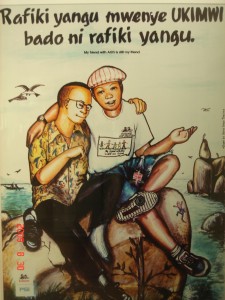

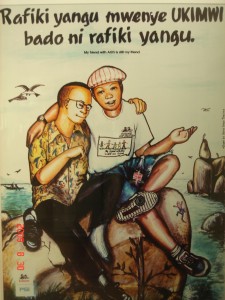

Surrounding the installation, representations of health in countries such as Tanzania, China and India were included. “Facing HIV/AIDS” explored the approaches these communities have to the AIDS epidemic. The stigmas attached to being diagnosed with AIDS in these societies prevent many from seeking treatments; therefore, the need for education programmes, community workshops and poster campaigns which aim to make it easier to discuss and practice safe sex. “Praying for Health” showed how certain communities use prayer and traditional medicine to treat their illness. In contrast to the British healing, it is a very different approach. Focusing more on the person and the higher being rather than the pharmaceutical companies and the business aspect, societies in Tanzania, India and China focus on the being and their needs. Although the treatment of such illnesses such as HIV/AIDS can not be done only through traditional healing, their approach should serve as a guide to western societies where a more humane way to treat patients. There needs to be an infusion between the two worlds.

"My friend with AIDS is still my friend."

Tags: Jeyla · Museums

September 2nd, 2009 · 3 Comments

I’m not one for long, verbose titles; I prefer to let my artwork (if a blog post could be considered such) stand on its own. I suppose that’s why The British Museum and The National Gallery appealed to me, because these museums are arranged in such a way that the art and artifacts are privileged over their context and allowed to speak for themselves. Information is available at both museums for those who want to learn more about an individual piece, but signage is simple and audioguides are discreet.

I devoted most of my time spent at The National Gallery to the 18th-20th centuries exhibit, which featured works by Monet, Manet, Picasso, van Gogh and Degas. The piece which affected me most viscerally was Vincert van Gogh’s “Sunflowers,” a painting which I had seen many times on postcards, coasters, prints hanging on water-damaged walls or in the only remains of my mother’s abandoned art degree – in her art books. Seeing this work in person was an incredible experience. Having the opportunity to experience the thoughts, emotions and perceptions of one of the world’s most renown artists though one of the world’s most renown pieces of artwork affected me very deeply. What struck me about works in both museums, but “Sunflowers” in particular, was the work’s enduring relevance diachronically. Though styles and historical contexts are particular to a piece of art and remain fixed, its meaning is mutable. This, I feel, is the true beauty of art.

At The British Museum, I had a similar reaction to seeing and touching part of a column which came from the Parthenon. It is amazing how these artifacts have managed to remain in tact and meaningful for thousands of years. One sign that caught my attention was one which told the story of how Lord Elgin brought pieces of the Parthenon back to England in 1806. The signage, as well as other historians and archaeologists, claims that Elgin essentially saved the artifacts from further destruction and preserved them by bringing them to England. However, now that Greece has the means to afford an appropriate Acropolis Museum, there is much debate regarding the British Museum’s collection of artifacts, uncluding a number of friezes.

Both The National Gallery and The British Museum seem to honor artwork and artifacts over their historical context. Though considering where these pieces came from is crucial in understanding their meaning, perhaps where they are going, such as the friezes and sections of column of the Parthenon, and their relevance to our culture in the present and future is what should be more important.

Tags: Anya · Museums