Whittaker’s thesis and stance on the reforming of Russia encompasses the two mentalities of Russia: the conservative history under autocracies and the desire for progress. She mentions that because Russians had only ever truly been governed under a strong, authoritarian leadership that there was an expectation of that way of societal structure (as nothing else had ever been implemented) where the state always came before the individual. However, she importantly notes the contrast that was brought about by reforming tsars. Once reforms were initiated into society, people began to demand more and more of their government and continuously wanted more and more reforms for a better way of life (as seen, and referenced in this article, to Mikhail Gorbachev with glasnost and perestroika). Thus, as western ideas flooded into Russia, the Russians constantly asked for more- but still under the mixed ideology of being under an authoritarian government. This left the tsars in a place where they had to continue to modernize Russia culturally yet maintain much of the control that had been taught to them as the way to govern Russian society.

Monthly Archives: October 2014

Peter the Great

Peter the Great strived to shape Russia into a systematic state focused on gaining nationalism through order. Inn 1722 after the Table of Ranks was established to clearly define roles in society however, Peter’s intentions never really formed. Russia’s theme of orderliness is exemplified here. Whether it be house-hold as seen in Domonstroi or general customary law such as the Pravda Russkaia; Russia has always been concerned with the well being of citizens and this was reinforced by the idea of orderliness. The Table of Ranks divided the upper/middle class into categories based on merit. An Admiral, or a chancellor would be a 1 while a artillery man or a college registrar would be a 13 and 14. Ranks were passed down from family and one would marry into a their future husbands rank. Russia has been constantly occupied with turmoil concerning ranks, for instance The Time of Troubles occurred because there was no one in the system to take the throne. Peter the Great intended to leave behind a system in which ranks would be the ultimate decider for claims and fill-ins. One of Peters largest goals was to make Russia more united, thus trying to put in this nationalistic system. He wanted to make Russians, excluded the peasantry, accountable for their state so they took pride in performing their civil duties.

1.) In what ways was “The Table of Ranks” a good idea? bad idea? over ambitious idea?

2.) How did Peter fulfill his goal of making Russia a prouder country?

Peter the Reformer

In general, Peter’s desire to modernize and Europeanize Russia led him to enact changes too quickly without enough thought of the effects on the peasantry. By focusing only on the upper classes of society, Peter created an even sharper division between the elites and the general population. While the elites were forced to embrace modern practices and assimilate these into everyday life, the general population had no understanding of why changes were being enacted, and found the changes to be irrelevant to them. The modernization of Russia was confined to a small group of people in a small area, leaving the rest of the population separate and uninvolved. Peter’s modernization was unnatural in that he did not make plans for it to occur gradually and widespread, but instead imposed many changes extremely quickly, focusing on only a small fraction of the Russian population.

By establishing the Table of Ranks, Peter intended to tie personal interests more closely to the interests of the state. By giving high rank and status to those he deemed to be most useful to society, Peter exercised authority not only over state matters but also over the definition of personal self worth. People were working for the approval of the tsar.

Back to the Land

Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s chapter, “Back to the Land” in Three New Deals discusses the concept of a “back-to-the-future movement” with the revival of “the region” (p 111). Fascism, National Socialism, and the New Deal all had reforms focusing on the decentralization of the state’s population. I found Stuart Chase’s perspective of this movement particularly intriguing. He argued decentralization was ideal for “maintaining and encouraging the handicrafts”(p 118). The main idea behind this movement was to restore the unity between nature and economy. The driving force behind this idea was the belief that a large, industrial economy was more problematic than a smaller, “crisis-resistant” economy (p 118). In Germany, these small regional settlements, landstadt, were overwhelmingly unsuccessful. The failure of landstadt was succeeded by the Industrie-Gartenstadt, which tied a community to large-scale industry.

National Socialist Propaganda used these settlements as a symbol of their architecture. However, these settlements did not contain the necessary power to fulfill this symbolic role (p 136). Schivelbusch ends this chapter by stating this orientation was shared with both Fascism and the New Deal. In what ways do you think these regimes shared characteristics with the National Socialists? If the landstadt couldn’t fulfill the symbolic power for propaganda, what could?

Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. “Back to the Land.” Three New Deals: Roosevelt’s America, Mussolini’s Italy, Hitler’s Germany, and the Rise of State Power in the 1930s. New York: Metropolitan, 2006. 105-37. Print.

Back to the Land: Restoring “Balance” and Morale

In Chapter 4 of Three New Deals, Wolfgang Schivelbusch discussed how the return to and the love for the land was an important component of Hitler’s Third Reich, Mussolini’s Fascist Italy, and FDR’s presidency. The Great Depression and the First World War devastated all three of the nations and balance and morale was completely destroyed. All three of these countries were in search for a response to both events to would build up the economy, as well as the collective community. The land symbolized both wealth and identity, and therefore, it became a crucial component in helping nations recover since it helped restore the balance and morale that was lost after the Depression and WWI. All three systems were in favor of state planning, which is the complete opposite of laissez-faire capitalism, a system that was strongly favored amongst Western nations and the United States.

Schivelbusch stated,”The common denominator among the various ideas in the various countries was the effort to restore some of the qualities of life that had been destroyed or seriously damaged by fifty (in Britain, one hundred) years of laissez-faire capitalism.” (Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Three New Deals, (New York: Picador, 2006), 110.) The revival of regionalism, agriculture, and the decentralization of the economy represent efforts to get rid of the industrialized and capitalist past that “destroyed” these nations in the first place. Furthermore, Schivelbusch added how the land and one’s native soil was seen as “reassuringly elemental and stable” as opposed to “what Edmund Wilson called the ‘gigantic fraud’ of pre-Depression prosperity.” (Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Three New Deals, (New York: Picador, 2006), 115). The way out of the Depression was to revive the “humane” preindustrial society and continue to move forward with technological advances. Would you argue that all three systems were illiberal since they looked for ways to incorporate the pre-industrial past into their modern governments? Why or why not?

The idea of returning to and gaining love for the land in addition to having its economic motives, also had the social motive of creating a community amongst the collective population. One of the many goals of going back to the land was to help create a new type of “organic” and “humane” citizen in contrast to the “mechanized workers” of the industrial period. (Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Three New Deals, (New York: Picador, 2006), 119). However, knowing the history of all three governments, particularly, Nazi Germany, the means used to create a master race were not humane, but were rather systematic. How can we explain this contradiction between nature and “mechanized” culture that pertains to the industrial age? Is there a medium in the case of Nazi Germany? Is there a medium in any one of these three systems or did they all fail to pull away from the “mechanized” culture of the industrial age?

Autarky & Nationalism

In Schivelbusch’s fourth chapter titled “Back to the Land,” the author discussed the term “autarky,” or national economic self-sufficiency, which became the watchword of the 1930s. More than just an economic concept, the idea of autarky was applicable to nationalism as well. Schivelbusch noted that by 1933, nationalism was more than one hundred years old, and its popularity rose and fell in cycles corresponding in contrast with cosmopolitanism. ((Wolfgang Schivelbusch, “Back to the Land,” in Three New Deals – Reflections on Roosevelt’s America, Mussolini’s Italy, and Hitler’s Germany, 1933-1939) (New York: Picador, 2006), 104)) However, the Great Depression led to the rediscovery of the nation and its embodiment (the state). The chaotic times incited a movement of nations looking inward and becoming more introverted and defensive, in hopes of achieving a self-sufficient economy immune to crises like the Great Depression.

Various initiatives were introduced to instill a sense of community and the rebuilding of domestic infrastructure. In general, all three governments hearkened back to times of pre-industrialization and advocated regionalism, decentralization of economic institutions, and the re-agriculturalization of the society. These initiatives were categorized collectively under the ‘back-to-the-land’ movement. The obsession with autarkic ideals was short lived however. While at the time of the collapse of capitalism it was logical to question whether or not industrialization had been a mistake, the presence of this mentality was brief. According to Schivelbusch, the reason for decline in these projects could be attributed to an ebbing in hostility by the middle class towards capitalism and industrial giants (( Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Three New Deals,133 )).

One reason why these initiatives were attempted was to further the development of nationalism by first focusing inward. A quote that I found particularly interesting was spoken by Mussolini about “nationalizing” people. Regarding this question, Mussolini said “After we’ve created Italy, the next task will be to create Italians.” (( Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Three New Deals, 109 )) Do you agree with this idea that the creation of a nation must come before the “creation” of a people? Why or why not? Can you cite other historical examples that demonstrate either side of this argument?

Autarky Envisioned

The idea of autarky was present throughout all of Europe as each nation was affected by the Great Depression. As the Depression impacted each nation’s economy, a new ideology needed to be introduced to the capitalist society. Individuals were against the rapidly growing materialistic and capitalistic world as it could be the only explanation for the Depression. But how was autarky envisioned in the totalitarian state such as Germany and Italy, alongside the democratic United States? In Schivelbusch’s Three New Deals, autarky can be explained beyond the economic standpoint. ((Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Three New Deals, (New York: Picador, 2006) )).

As the Depression hit, the rush to create a self-sufficient economic was significant. If a nation was unable to support themselves the nation would suffer even more. Regionalism was introduced as well as inner colonization. This inner colonization as Schivelbusch explains brought forward the importance of nationalism. The nation must find opportunities in which individuals could become an nation and develop a sense of national pride. Propaganda and public works projects financed by the state were established to find this national pride within the community. Individuals were brought to live in small communities in where there were able to develop a sense of family within the state.

Establishments of public works projects and state-funded propaganda gave the government a new view of nationalism and the impact it could make to suppress the effects of the Depression. While several of these public works projects failed such as the settlements located on the outskirts of major cities, nations were able to develop a national pride that allowed them to gain strength that was needed in WWII.

Blut und Boden — Primordialism in Schivelbusch’s Three New Deals

Primordialism is an ancient form of nationalism that is rooted in mono-ethnic relations. As opposed to modernists who promote an imagined, mental conception of nationalism that is possible between multiple ethnic groups, primordialists assert that nationality is based on a common gene pool which creates physical attachments in a singular people. Beyond imagined community asserted by modernists, primordialists believe blood relations tie individuals together through the bonds of kinship, clanship, and tribalism founded on communal inheritance. Do you believe primordialism (mono-ethnic groups connected through blood ties) or modernism (multi-ethnic groups that feel an affinity for each other through created traditions, e.g. The Pledge of Allegiance) is a more cohesive form of nationalism?

As Schivelbusch discusses in his 4th chapter, “Back to the Land”, ((Wolfgang Schivelbusch, “Back to the Land,” in Three New Deals – Reflections on Roosevelt’s America, Mussolini’s Italy, and Hitler’s Germany, 1933-1939) (New York: Picador, 2006), 104)) primordial nationalism played a large part in the rise of authoritarian regimes of the 20th century. After liberal politics and laissez-faire capitalist economies seemed to lead to the crash of 1929, rejection of industrial and international mechanisms that went along with them was the norm thereafter. To Schivelbusch, loss of public trust in democracies because of the Great Depression was essential for charismatic leaders like Mussolini and Hitler to establish rule through authoritarianism in the 1930s. ((Schivelbusch, Three New Deals, 106)) Nations turned inward instead of outward during national revivals in place of imperialist expansions. The quest for Lebensraum and Fascist colonization would only seem possible after domestic rebuilding and communal reconnection.

In an attempt to imitate the past successes of simpler, pre-modern times regionalism, decentralization, reagriculturalization, and the “organic citizen and society” were all promoted as a return to primordial ties of the homeland in the ‘back-to-the-land’ movement. The Nazi ideology “Blut und Boden” (blood and soil) epitomized this ideology — eugenic authenticity of a naturally superior Volk living on collectively-worked territory. ((Schivelbusch, Three New Deals, 112)) Handicrafts and labor tied to the land were promoted as the basis of an autarkic economy. Mechanical and artificial constructions of industrialization were deemed part of a ‘pseudo-community’ that must be reversed for a return to a more elemental, natural national life. ((Schivelbusch, Three New Deals, 120)) After a complete return to pre-industrial ways of life was eventually rejected as industrialization was increasingly seen as an irreversible mass movement, “a Utopian vision of a new, crisis-resistant synthesis of town and country, industry and idyll” ((Schivelbusch, Three New Deals, 126)) was promoted, espoused particularly by the concept of a non-specified laborer (farmer-factory worker) and Roosevelt’s term ‘rural-urban industry’ which he believed “would be crisis-proof and crisis-resistant”. ((Schivelbusch, Three New Deals, 127)) Do you agree with Roosevelt’s assertion that the most stable, balanced, self-sufficient industry would effectively maintain a bureaucratically controlled equilibrium of natural and artificial products?

The Age of Propaganda

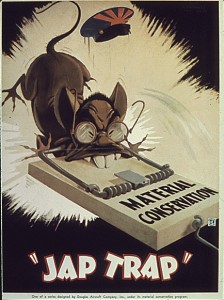

“Jap Trap,” World War II propaganda poster, United States Information Service, 1941–45. Densho Digital Archive, http://www.densho.org/.

“Propaganda can tip the scales,” claims Schivelbusch in regards to state influence in times of political turmoil in his Three New Deals. (85) The usual dialogue on the topic of interwar propaganda mostly elicits imagery associated with the USSR and Nazi regime, but what about the propaganda and control by the United States government? This is an example:

This blatantly racist imagery not only compares the Japanese to rats, it also depicts the rat with the physical stereotypes American’s gave the Japanese during the time. The squinted eyes, protruding teeth, and cartoonishly animated circular spectacles reappeared throughout anti-Japanese propaganda. The simple process of dehumanization of the enemy through animation also appears commonly in the anti-semitic propaganda perpetuated by the Nazis.

The Nazis as well as America assimilated the rat with their enemies. Rats are grotesque, parasitic, and carry disease. Essentially, they are an animal no one loves. It is certainly easier to identify propaganda that is new or foreign, however, after those images are presented repeatedly they become automatically associated with the intended concept and sink into the subconscious. This, in effect, is what makes it so powerful.

If an audience is being persuaded without realizing, can they stop it?

New Man the Hero?

The composition and fate of the hero has been the subject of culture and literature since antiquity. The idea of one individual, surpassing common constraints and achieving greatness has long held an important place in the human psyche. The creation of the New Man, by both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, transformed the concept of a new , modern human being into their own unique ideal. Peter Fritzsche and Jochen Hellbeck argued in Beyond Totalitarianism that the Nazi hero exemplified the optimal Aryan purity and perfection, while Soviet Russia allowed every individual to achieve greatness through self-reformation into the proletarian socialist.

The relationship between the physical body and this transcendent state of being occurred in both ideologies. Soviet Russia concentrated its efforts in creating the ideal proletarian New Man by changing the human body through modernization and mechanization. One example, Bogdanov underwent blood transfusions in order “to create a communal proletarian body.” ((Peter Fritzche and Jochen Hellbeck, “The New Man in Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany,” in Beyond Totalitarianism, ed. Michael Geyer and Sheila Fitzpatrick (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 316)) In this case the individual attempted to change their blood, the very essence of their being, in order to create a New proletarian Man. Although the physical transformation of the body into the New Man faded from mainstream Soviet ideology, the body (this time young, healthy, and robust) remained a secondary indicator of the ideal Soviet New Man. ((Fritzche and Hellbeck, “The New Man” in Beyond Totalitarianism, 320))

Similarly, Nazi Germany utilized the physical as a representation for the important ideas meant to create the New Man. The racial purity espoused by the Nazi Party was meant to guarantee a superior race of human beings capable of world domination; by perfecting the body through race the German people could once more achieve greatness. ((Fritzche and Hellbeck, “The New Man” in Beyond Totalitarianism, 328)) The body must therefore be continuously transformed through generations of racially pure matches in order to create the ideal New Man. Moreover, the idealized Aryan eclipsed racial purity and applied to clothing, exercise, and, diet. ((Fritzche and Hellbeck, “The New Man” in Beyond Totalitarianism, 329)) The New Man relied on physical and aesthetic, not just mental enlightenment; similar to the concept of the New Man in Stalinist Russia.

In both Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany, the regimes attempted to create a New Man by manipulation not only of the mind, but also the body. How does this physical manipulation relate to the construction of the modern state?