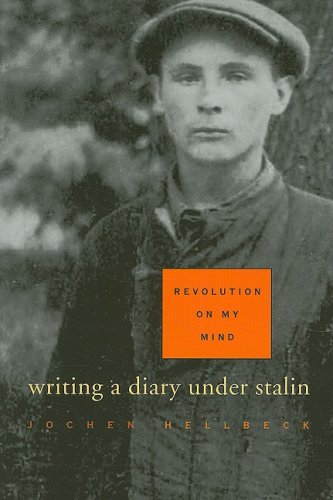

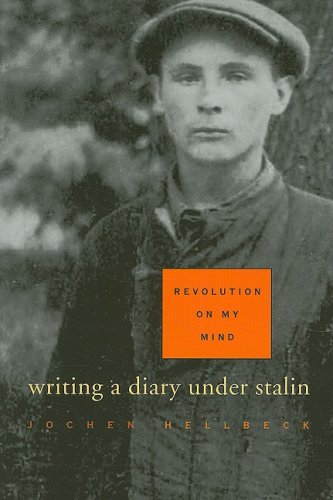

Hellbeck’s interpretation of Podlubni’s diaries depict a man trying to conform to the morals of his state. He goes through many organizations and practices so as to become the ideal Soviet citizen. Each attempt is recorded in Podlubni’s diary. But, at a point in the piece, Hellbeck argues that this private journal may not reflect Podlubni’s true thoughts, but his desired thoughts. He introduces the idea that the diary could be Podlubni’s tool of turning himself, of influencing his own nature.

Has diary writing survived? Is there something comparable now?

Has diary writing survived? Is there something comparable now?

As technology has sped up society, and physical writing has fallen out of fashion, many of the younger generation have turned to electronic styles of diaries, favoring short and typed passages over the traditional form. Today’s most consistent source of social records, it could be argued, would be social networks. Any incident out of the ordinary, and many too that are ordinary, will end up here. But, the public nature of these sites lacks the privacy of Podlubini’s diaries and, therefore, may color the style of ‘reporting’.

Does this influence the blogger any differently than Podlubini is in his diaries?

In his writing, Podlubini attempts to instill and record a set of Soviet morals — a strong will, a good work ethic, patriotic intentions. He records his successes and chides himself at his ideological shortcomings.

“30.12.1933 […] With full confidence I can say that this year I have received nothing. Studied at the FZU— with bad results. Began to study in middle school— also with bad results. I am neglecting my classes horribly, lagging behind in all subjects. I don’t have enough willpower to control myself. Right now I have a big, huge, horrible weakness of will. This is the cause of all my troubles, this is my biggest deficiency.”

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. Stalinism : New Directions.

Florence, KY: Routledge, 1999. p 100.

Podlubni knew that his diaries, like many private possessions at the time, may be confiscated by the State on any grounds and at any time. This is one of Hellbeck’s arguments to caution us away from the complete truthfulness of Podlubni’s records.

So, were these diaries entirely private?

Consider them in the context of popular social networks. Imagine the most cautious user — only friends can see their posts, does not use an accurate identifying picture, and only accepts requests from close, close, friends. Their records can be obtained by any determined individual, similar to the Stalinist state. But, our user runs this risk. On such sites, our user hopes to associate and connect with like-minded individuals. Is this not what Podlubni hopes to accomplish? A connection with the other members of his State through the fashioning of his personality, of his “Stalinist soul”.

Consider them in the context of popular social networks. Imagine the most cautious user — only friends can see their posts, does not use an accurate identifying picture, and only accepts requests from close, close, friends. Their records can be obtained by any determined individual, similar to the Stalinist state. But, our user runs this risk. On such sites, our user hopes to associate and connect with like-minded individuals. Is this not what Podlubni hopes to accomplish? A connection with the other members of his State through the fashioning of his personality, of his “Stalinist soul”.

But, if this is to be an accepted analogy, what of the many users that ‘over-post’ or flood the site with over dramatized postings? Are they just asking for attention, taking advantage of the publicity of the networks? Does this disprove the connection to private diaries?

No. The basis of social sites is to establish oneself on the web. It is a defining of self. While this may be fabricated and unlike the true self, it is often an expression of a self the users want to become. They fabricate an ideal “public self”, similar to Podlubni’s fabrication of a real “Stalinist soul” — a strong individual and a strong worker.

Given the entries we see online today, what morals can be in our souls?

Has diary writing survived? Is there something comparable now?

Has diary writing survived? Is there something comparable now? Consider them in the context of popular social networks. Imagine the most cautious user — only friends can see their posts, does not use an accurate identifying picture, and only accepts requests from close, close, friends. Their records can be obtained by any determined individual, similar to the Stalinist state. But, our user runs this risk. On such sites, our user hopes to associate and connect with like-minded individuals. Is this not what Podlubni hopes to accomplish? A connection with the other members of his State through the fashioning of his personality, of his “Stalinist soul”.

Consider them in the context of popular social networks. Imagine the most cautious user — only friends can see their posts, does not use an accurate identifying picture, and only accepts requests from close, close, friends. Their records can be obtained by any determined individual, similar to the Stalinist state. But, our user runs this risk. On such sites, our user hopes to associate and connect with like-minded individuals. Is this not what Podlubni hopes to accomplish? A connection with the other members of his State through the fashioning of his personality, of his “Stalinist soul”.