Chapter IV of George Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier made many interesting points about poverty and housing conditions in Interwar England. Orwell developed a very in depth study of the living conditions and how this may have affected the psyche of the inhabitants.

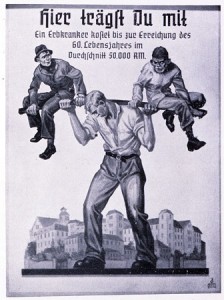

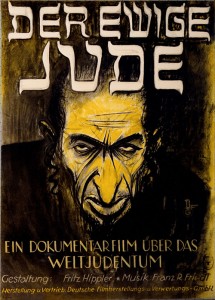

The Interwar Period was very concerned with behavior and order, especially in the wake of the Great War’s chaos. Psychology was one way in which many scholars began to try to understand the actions of both society and the individual. This type of study also began to influence other academic areas, like History, Anthropology and Literature. Orwell demonstrates, in questioning the behavior of this group, how various areas of study had become more interwoven.

Orwell at one point in Chapter IV discusses how some impoverished families portrayed themselves as more economically comfortable. Many Corporation houses seem to have been filled with well-maintained furniture; these items seemed to belong in a more financially stable house—a family that is not living at or below the poverty line. Orwell argues “it is in the rooms upstairs that the gauntness of poverty really discloses itself.” (60) He believes that it is a matter of pride to protect the nicer, more valuable pieces of furniture so that the family can appear to be less impoverished. These had most likely been passed down within the family throughout generations. It is the items that need to be bought every few years or months that were more difficult for these families to afford (i.e. bedclothes), and therefore, fewer families in more desperate financial situations had access to many basic items, like bedclothes.

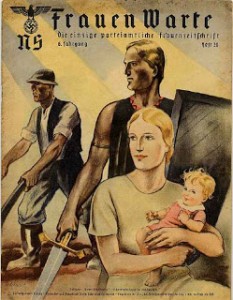

This excerpt shares some similarities with Leora Auslanders’s article “’National Taste?’ Citizenship Law, State Form, and Everyday Aesthetics in Modern France and Germany, 1920-1940.” Both pieces referred to the tendency to “keep up with the Joneses.” How did this idea, needing to present a better image to the public or society, reflect larger themes from this period? Was this a reaction to the chaos of the war? Or a reaction to the uncertainty of the period? Or would this type of behavior have occurred regardless of wars, death and economic troubles?