In this overt example of interwar propaganda, the practice of eugenics is promoted through a poignant visual and textual analogy to agriculture. The double meaning of the key term “seed” is utilized in a comparison between spreading healthy plant seed for a bountiful harvest and spreading healthy human “seed” for the purposes of procreation, specifically the creation of a physically fit, mentally proficient, racially pure population.

The first block of text that appears at the top of the poster, “Only healthy seed must be sown!”, alludes to the exclusionist principles of eugenics. People who were deficient in physical or mental health were considered unfit to procreate. More generally, anyone incapable of making an economic contribution to the state through gainful employment were subject to the scorn of negative eugenics (Mazower, 96). Such members of the population were considered sources of “bad seeds,” so to speak, a threat to the purity and longevity of the nation in question.

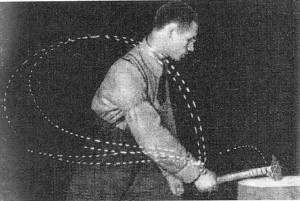

The textual motif of the poster stands in contrast to the bright and optimistic image of the farmer, portrayed as a literally shining example of the robust and productive citizens that eugenicists aimed to create. As Mark Mazower states in Dark Continent, eugenicists “believed that it was indeed possible to produce ‘better’ human beings through the right kind of social policies.” (91) This logic was employed by several European nations during the interwar period, most notably Great Britain, Russia, and Germany, the latter applying the simplistically and deceptively positive term “racial hygiene” to the practice of eugenics. (Mazower, 92).

This poster is a pithy snapshot of the dangerous ideological ground being tread by interwar governments in Europe. While the calculated and “logical” attributes of eugenics (as discussed in class) held several appeals for the recovering European governments after WWI, the concomitant dehumanization of the population in the eyes of the state may have in fact planted the “seeds” of social tension and injustice that helped steer the continent toward WWII. (Mazower, 97-98)

Image Source: http://www.niea.unsw.edu.au//sites/default/files/projects/323.jpg