USING THE LATIN WIKIPEDIA IN INTERMEDIATE AND ADVANCED COLLEGE LATIN CLASSES

by Anne Mahoney, Tufts University, anne.mahoney@tufts.edu

[note: this article is re-published from The Classical Outlook 90.3 (Spring 2015), pp. 68-90. Thanks to the author and to CO‘s editor Mary English for permission to do so.]

Most people are aware of Wikipedia, the open, collaborative encyclopedia. But Wikipedia exists in over 280 languages, not just English, and one of the larger versions is in Latin. Vicipaedia, the Latin Wikipedia (http://la.wikipedia.org), has over 100,000 articles on topics ranging from Gaius Valerius Catullus to Dinosauria to The Simpsons. It is a good general encyclopedia, written in good classical Latin. It’s also a world-wide community of Latinists. In this essay, I will introduce Vicipaedia and give some pointers on working with it: reading, researching, or editing.

I. Overview

Vicipaedia Latina is moderately large, one of the fifty largest Wikipedia versions, with over 108,000 articles. Though it’s only about 1/40th the size of the English version, measured by number of articles, it’s about 1/18th the size of the Dutch, German, Swedish, and French versions and 1/10th the size of the Spanish version. There are about 40 very active editors and 300 regular contributors, making hundreds of edits every day. Vicipaedia contains all of the “1000 Articles Every Wikipedia Should Have,” a list compiled by the broader Wikipedia community. Articles in Vicipaedia are generally not translations from English Wikipedia, but are freshly written in Latin.[1]

Wikipedia, in any language, does not pretend to give the final word on any subject — rather the opposite, in fact. It is a reference work, not a work of scholarship, intended to give general orientation to a subject, with pointers to other resources. Within those limits, Vicipaedia does a very good job; its information is accurate, and every article is required to cite sources, to have links both to and from other Vicipaedia pages, and to have links to resources outside Vicipaedia — assuming they exist: after all, not everything in the world is on the Web. English Wikipedia has more and longer articles, but Latin Vicipaedia, like all the other official Wikipedia versions, maintains the same standards of quality. Wikipedia is one of the best general encyclopedias currently available,[2] and certainly the most convenient; its Latin version is not only a useful reference but a significant work of neo-Latin.

Vicipaedia covers the same range of articles as any general-purpose encyclopedia, but, not surprisingly, it is particularly strong on subjects in classical antiquity. For example, the article on Caesar is long, with illustrations, a time line, and links to copies of Caesar’s own works and Suetonius’s life (outside Vicipaedia). On the other hand, the article on George Washington is much shorter and that on Louis XIV of France shorter still; both of those rulers have major articles in English Wikipedia.

Just like all the other Wikipedia versions, Vicipaedia is a collaborative encyclopedia. Anyone can edit pages, either anonymously or with an official user name. A group of magistratus (called “admins” or “sysops” in English Wikipedia), elected by the community, oversees the project, sending greetings to new users, checking for problems, and so on. Several automated jobs run over the system as well, verifying that pages conform to the basic standards. For example, if a page has no links to other Vicipaedia pages, or no links from other pages, an automated job will notice this and put a flag on the page to notify users of the problem.

Regular contributors to Vicipaedia are classical scholars, teachers, students, and other interested people from all over the world. Some of the most prolific editors are in France, Germany, Switzerland, the Philippines, Taiwan, Britain, Austria, Finland, Canada, and various parts of the US. Our native languages include English, French, Italian, Finnish, Spanish, Hungarian, and German. Some write under our real names, some use aliases or nicknames, and some remain anonymous. We can discuss Vicipaedia and particular articles at the “Vicipaedia Taberna” (a page for general discussion), the discussion pages associated with each article, and users’ own discussion pages. On those pages, conversation takes place both in Latin and in other languages, most often English and German. Vicipaedia is run by consensus; if something needs to be done, users just do it, or if it’s a large or complicated task, we begin by proposing it on a discussion page. Anyone interested joins in the discussion, and once everyone is agreed on what to do, we work together to make the changes. For example, last year a user proposed redesigning the front page. He made a mockup and raised the question in the Taberna. Over the next month, a dozen users discussed the appearance of the page: how to greet users, how many columns to use, what other features should be added. When everyone was content, the new design was put in place.

The first version of Wikipedia was in English, created in January 2001, but versions in other languages followed quickly.[3] Latin Vicipaedia got its first articles on 25 May 2002: Nuntius, giving a brief list of sources for news in Latin; Mensis, defining the term and giving the Latin names of the months, starting from March in Roman fashion; Suecia, because the editor adding these pages was from Sweden; and Iasser Arafat, for whom the entire content at first was “Jasser Arafat praesidens Palaestinensium est.” At the end of its first year Vicipaedia had just a thousand articles. By the end of 2006 it had ten thousand, and during 2007 it began to grow more rapidly. The hundred-thousandth article arrived on 18 December 2013; it was Iosephus Škoda, a brief sketch about a Viennese doctor, 1805–1881. At this writing Vicipaedia has 108,307 articles.

Vicipaedia is not the first on-line collaborative encyclopedia in classics; the Suda On Line started in 1998 and has involved over 150 translators, editors, and programmers.[4] But whereas Suda On Line contributors “must request authorization and must ask to be assigned specific entries” (Mahoney p. 100), access to Vicipaedia is entirely open. Anonymous users contribute every day. And while the Suda On Line is finite and bounded, since it is a translation of and commentary on the existing Byzantine encyclopedia, Vicipaedia is unlimited: it accepts articles not only on classical antiquity and the Bible, like the Suda, but on everything from movies to types of cheese.

II. Reading Vicipaedia

So how can you use Vicipaedia? First, let’s look at how it works. We begin with the front page:

The pull-down menus labelled Ars & litterae, Scientia, Societas, Technologia, and Lingua Latina give access to high-level, general articles that are good starting places. For example, under Scientia are links to such articles as Chemia, Mathematica, Anthropologia, and Philosophia. The front page also shows the month’s featured article, picture, and sound, all chosen by Vicipaedia’s contributors. The featured article here, Gerasimus Lebedev, is about an 18th-century Russian scholar and theater producer; the Latin article is much longer than the article about him in English Wikipedia. Featured articles of recent months have included Plato’s Theatetus, Litterae Civitatum Foederatarum, Canada, and Feles. Below the Pagina Mensis is a section of news, with recent headlines. Key words in each section of the page are hyperlinks to articles within Vicipaedia.

At the top right of this page, and of every Vicipaedia page, is a search box. If you enter the title of an article here, you’ll go directly to that article. Articles often have alternate names — the page whose official title is Publius Ovidius Naso is also called Ovidius and Naso, for example — and if you search for something that is not the name of a page, you’ll get a list of pages whose names match your search terms. Here, for example, is a search on “meow,” which shows that this phrase appears in the articles Feles and Communicatio felium, not surprisingly:

For each page you can see a snippet of the text near the search word, the size of the page in kilobytes (“chiliocteti”) and words, and when it was last changed. There is also a link that would allow you to create a page called Meow.

Finally we come to the articles themselves. Here is a short one by way of example:

The title of the page, at the top and in the browser titlebar, is Quintus Ennius. Some words in the text of the page are hyperlinks to other Vicipaedia pages, such as poeta; these are blue. Others, in red, are links to pages that do not yet exist, such as praetextatas. The page has an illustration, showing Ennius as Raphael imagined him in his painting “Parnassus,” and Raphael’s name in the picture caption is also a hyperlink. A reader — perhaps an intermediate Latin student — who doesn’t know some of the terms in the article, like Naevius or Magna Graecia, has only to follow the links to learn more.[5]

At the far right of the page title, just above the illustration, is a small dot. On this page it’s a green dot, indicating that this page is in good Latin. Other pages may have a red dot, indicating that the Latin is not good, or a larger notice indicating that the Latin is positively poor. Some pages have a yellow dot (or no dot at all), which means that no one has yet judged the quality of the Latin. The convention is that editors don’t grade their own pages, but may grade pages they haven’t written; everyone is encouraged to fix grammatical errors.

At the bottom of the page are names of categories, connecting related pages. For example, Ennius is in the categories of “Poetae Latini” and of “Nati 239 a.C.n.” The category names are hyperlinks to lists of other pages in the same category — other Latin poets, for example. Categories can belong to other, more general categories, as “Poetae Latini” belongs to the categories “Poetae” and “Auctores Latini.” They can also include narrower categories, as “Poetae Latini” includes “Poetae Latini Brittaniae.” Thus the category structure classifies Vicipaedia’s articles by topic, helping readers explore a subject, drill down for more detail, or broaden scope to more distantly related areas.

At the left-hand side, under the heading Linguis aliis, are links to the parallel page in other Wikipedia versions. We see that there are articles about Ennius in Esperanto and Basque (Euskara), among other languages. When you move your mouse over the name of a language, you’ll see the name of that language’s page and the English name of the language. For example, if you mouse over “Euskara,” you’ll see “Ennio — Basque” next to the mouse pointer. A list like this appears in the left sidebar of every page in every Wikipedia version, and you can use it as a quick-and-dirty multi-lingual dictionary: for example, from the English page “Cat,” the links show you that a cat is called chat in French, pōpoki in Hawaiian, paka-kaya in Swahili, mèo in Vietnamese, and, of course, feles in Latin.

The Historiam inspicere link next to the search box above the page title shows the revision history of the page. From the history, we see that this article has been edited 71 times, by fourteen named editors, five anonymous editors, and fifteen automated processes. When it was first created, in May 2003, the article contained a single sentence: “Q. Ennius, poeta, morit. CLXIX ante Ch.” The text was expanded in June 2006; the illustration was added in September 2011. In February 2008 it was judged to be good Latin, and marked accordingly.

You can use Vicipaedia to get general background on a subject, as you’d use any other encyclopedia. Of course, since it is an encyclopedia, students shouldn’t be citing it in scholarly papers, just as they shouldn’t cite Encyclopedia Britannica or other print encyclopedias. But to find out when Ennius lived, or other basic facts, Vicipaedia is convenient. It’s particularly useful if you’re preparing a mini-lecture in Latin, for example about an author a class is just starting to read.

Students can also read the articles on their own. Here is one exercise I have used with intermediate-level students (third semester in college):

You have read the story of Lucretia from Valerius Maximus and from Eutropius, and will next read the version from Titus Livius (usually “Livy” in English). Look up each of these authors in Vicipaedia and answer the following questions about them:

- Quando vixerunt hi scriptores? Quis est maximus natu, quis minimus?

- Quid scripserunt?

- Ubi vixerunt?

- Quid significat “annales”? Qui inter hos scriptores annales scripserunt?

- Libri horum scriptorum non omnes sunt annales. Quid et quales sunt alii libri?

- Follow one link within Vicipaedia from each of the three articles. Which link did you choose? What did you find there? (Links that go out of Vicipaedia are marked with a small arrow — don’t use those for this purpose.)

- Using the “historia” of the pages, identify three named Vicipaedia users who have worked on these articles; find real people, not users with “bot” in their names. Who created the pages? Who was the most recent editor? Look around at their user pages: what can you say about these users?

In this exercise, students are introduced to Vicipaedia and asked to gather information from articles. They are also encouraged to explore: following links within pages, looking at the history of a page, looking at users’ pages. This exploration not only demonstrates some of the tools and conventions of Vicipaedia (and Wikipedia in general) but also gives them a chance to read a bit more Latin.

A later exercise in the same semester was designed to expand students’ awareness of Latin literature:

Return to Vicipaedia Latina. Read the pages entitled Litterae Latinae and Certamen poeticum hoeufftianum; explain briefly what each is about. Choose one name from each page that you don’t already know about (and for which there is a page in Vicipaedia — a blue-linked name rather than a red link); follow the link and read the resulting page. Which names have you chosen? What have you learned about them? You may write these answers either in English or in Latin.

The two pages named here are largely lists of authors. Litterae Latinae says a bit about the main periods of Latin literature, then lists authors from each period. Certamen poeticum hoeufftianum describes the competition, held from 1844 to 1978, and lists all the winners.[6] Students were surprised to find out how much post-classical Latin literature there is, and how many authors they’d never heard of. While articles about major authors like Vergil and Ovid can be quite long, the articles about other Latin authors are generally shorter, so this is a fairly tractable assignment for intermediate-level students.

III. Editing Vicipaedia

In more advanced classes, I have asked students to contribute to Vicipaedia. To do that, it’s necessary to learn how editing works. Anyone who knows Latin is encouraged to edit, just as anyone who knows English is welcome to contribute to English Wikipedia. Students should probably wait until they can write a reasonably correct paragraph — editing Vicipaedia isn’t necessarily a good exercise in Latin 1 or 2 — but high-intermediate to advanced students often enjoy contributing, interacting with other editors, and creating something generally useful.

To get started editing, simply click the “Recensere” link at the top of almost any page. Vicipaedia’s “visual editor” lets you work with the text of a page much as you would in a word processor. It’s also possible to edit the wiki markup directly (with the “Fontem recensere” link) but this is rarely necessary.

The editing display looks much like the page itself, with a couple of tools at the top. Note that the browser title bar now says “Recensio paginae,” to remind you that you are using the editor.

The “Paragraph” tool lets you create section and sub-section headings. The underlined capital A gives a list of character format options: bold, italic, and so on. The next image, which looks like a couple of links of a chain, lets you add a link to another Vicipaedia page. If you click on a word that is already linked, you will see the name of the target page. If you select a word or phrase that is not yet linked, then click this tool, you can supply the name of another page to be linked to, by default exactly the same as the word or phrase you’ve selected. The next tool lets you add a list, like the one-element list under “Vide etiam” in this page. The “Insert” tool helps you add special characters, illustrations, mathematical formulas, or other unusual features. Finally, next to the “Abrogare” button is a tool for page options, in particular for adding the page to suitable categories. Once you’ve made changes, the “Save page” button at top right will be available, and when you click that, your changes will be saved and immediately visible to other readers.

What should a page contain? The conventions for Vicipaedia articles are documented at Vicipaedia:Praefatio and the pages linked there. Pages should always start with a definition or identification of the headword; this is called the “A est B” convention. Examples are “Feles est species parvorum mammiferum carnivorum familiae Felidarum,” or “Arithmetica est disciplina numerorum.” Ideally, a page should include an illustration, references to sources outside Wikipedia (whether on line or not), and links to other pages within Vicipaedia.

Vicipaedia maintains lists of pages needing particular kinds of improvements, and these can be good places to start editing. Students may expand on short pages (called “stipulae” or “stubs,” and in Categoria:Stipulae and its sub-categories), correct poor Latin (see Categoria:Latinitas), add captions for images (see Categoria:Imago sine descriptione), and so on; see Categoria:Corrigenda for a general list of categories of pages needing work. Of course students may also add pages, particularly pages that are linked but do not yet exist (shown as red links).

Here is an assignment I have used with advanced classes:

In this assignment, you will add an article to Vicipaedia, the Latin version of Wikipedia. Begin with the article Quintus Horatius Flaccus. Find a link either in that article, or in an article linked from that article, to a page that does not exist (the link will be red), and create the missing page. Your article should be at least 50 words long, preferably at least 100, so choose a topic about which you can write that much.

Some tips on the process:

- If you don’t already have one, create an account for yourself, so that your edits can be identified. Do this with the “conventum creare” link at the top of the page. If you already have a global account in Wikipedia, it will also work in Vicipaedia.

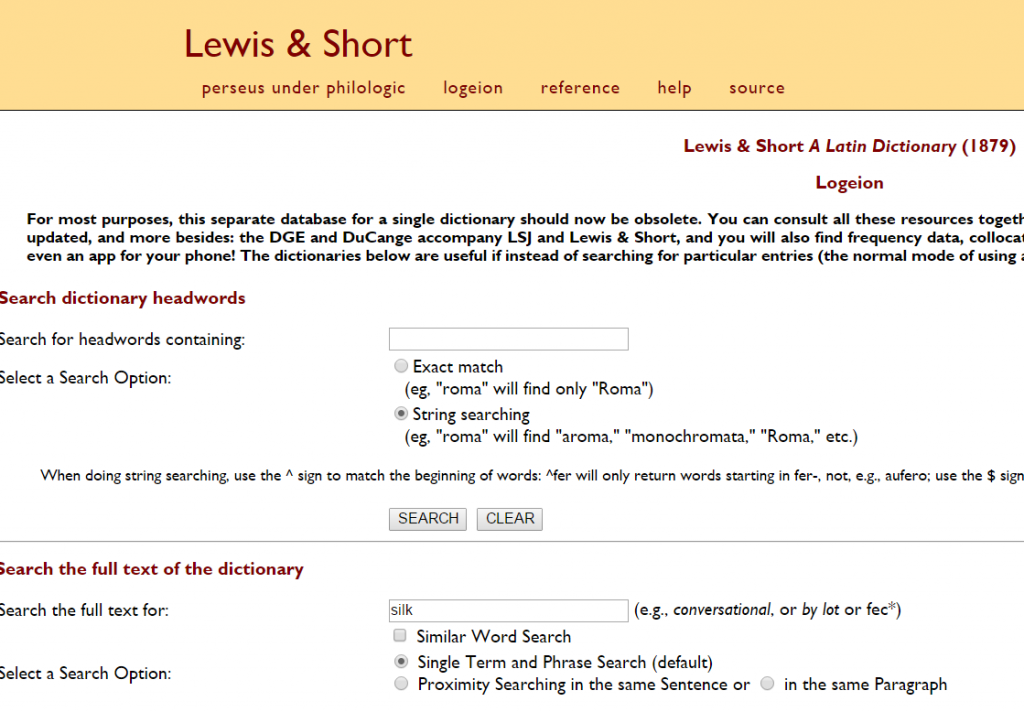

- If you have not edited Wikipedia before, read the usage information, in the English or Latin versions. If you have not edited Vicipaedia, even if you have edited English Wikipedia or the versions in other languages, read the help text specific to the Latin version. Begin with “Adiutatum” under “Communitas” on the left side of the screen. The information about conventions for writing neo-Latin is particularly useful. The page Lexica Neolatina has links to an assortment of on-line dictionaries.

- Set your preferences using the “Preferentiae meae” link at the top of the page: you can change the interface language (Latin is fun, but English is OK too), indicate your gender, change the look of the screen, specify how dates and times should be displayed (24-hour or 12-hour clock, and so on), and tweak the default options for searching. I recommend you set the editing options to remind you about the edit summary you should add whenever you update a page; this is under “Mensura capsae verbi.”

- Create your new page, following the standard editorial conventions. When you click on a red link you will get a new, empty page to start work in. An article must start with a sentence of the form “Nomen est …,” using the name of the person or thing you are writing about and marking it as boldface.

- Make sure to cite sources, including Horace’s text or whatever else is appropriate.

- Mark the page as belonging to a suitable category, using the Category tool from “Page options” at the top of the page.

- At the top of the page, use the “Insert” tool to insert either the template L, to indicate that you are reasonably confident of the grammar and style of the page, or tiro, to mark the page as written by a beginner. In either case, another user will (sooner or later) edit the page and assign it a level of latinitas.

- If possible, add a suitable illustration; use “Insert” and “Fasciculus” to get a rudimentary keyword search of available illustrations. There may or may not be a suitable illustration, depending on the topic you’ve chosen.

- Save your page. The next day, come back to it and look at changes other users have made.

- They will correct things or indicate things that need correcting. Fix, refine, improve, and continue to monitor changes made by the rest of the Vicipaedia community. You are encouraged to edit each other’s pages; I myself will not edit your work before the assignment is due.

- Don’t hesitate to ask the editors for help if you need it, using the “disputatio” link on the page you’re writing, the Vicipaedia taberna linked from the sidebar, or other help links scattered through the system.

Students doing this for the first time generally add fairly short articles, but useful ones. They are also delighted to receive the traditional Vicipaedia welcome message on their user pages, and to see that other users have read and improved their new articles.

IV. Conclusion

Vicipaedia is an encyclopedia, a Latin resource, and a community, and it grows every day. Anyone who knows Latin can read it and contribute to it. I’ve used it with undergraduate and graduate students in classes ranging from Latin 3 to a graduate composition course. In this article you’ve seen some of the things it can do, and some of the things you could do with it.

Bibliography

Dalby, Andrew. The World and Wikipedia: How We Are Editing Reality. Somerset: Siduri Books, 2009.

Giles, Jim. “Internet Encyclopedias Go Head-to-Head.” Nature vol. 438 (15 December 2005), 900-901.

Giustiniani, Vito R. Neulateinische Dichtung in Italien, 1850-1950. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1979.

Helmlinger, Julien. “La déclinaison en latin de Wikipédia dépasse les cent mille pages.” ActuaLitté, http://www.actualitte.com, 24 January 2014.

Lih, Andrew. The Wikipedia Revolution: How a Bunch of Nobodies Created the World’s Greatest Encyclopedia. New York: Hyperion, 2009.

Mahoney, Anne. “Tachypaedia Byzantina: The Suda On Line as Collaborative Encyclopedia,” Digital Humanities Quarterly 3.1 (2009), http://digitalhumanities.org/dhq/, reprinted in Changing the Center of Gravity, ed. Melissa Terras and Gregory Crane, Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2010, 89-109.

Footnotes

[1] I will use “Vicipaedia” to refer to the Latin encyclopedia, and “Wikipedia” to refer to the project in general, in English and in other languages.

[2] On the quality of English Wikipedia see Dalby p. 220, Lih p. 208, and Giles p. 900-901.

[3] Lih gives the timeline; creation of Wikipedia p. 64, of other language versions p. 139, and chapter 6 generally. The hundred-thousand-article milestone was noted for example by Helmlinger.

[4] Mahoney 2009 is an overview of the project; her section “SOL and other projects” (p. 100-104 of the 2010 reprint) compares the Suda translation to Wikipedia and similar projects.

[5] This is presumably obvious to experienced web users, but occasionally students don’t realize it, and pull out another reference work or do a brute-force web search to get a gloss for a name, rather than just clicking the Vicipaedia link right on the screen. So if you’re using Vicipaedia with a class, it’s worth pointing out that blue words link to more information.

[6] For a general description of this competition see Giustiniani p. 6, 15, 99-108.