Comic artist and theorist Scott McCloud, author of Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (1993), spoke at the recent conference Visual Learning: Transforming the Liberal Arts, at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota.

Of the many fascinating points in his keynote speech about the techniques of visual communication and learning, one was a critique of the way presentation software is commonly used, with outline slides that statically reproduce a series of points that a speaker is making. McCloud’s active principal, brilliantly put into practice in his own show, is synchronization: “When I’m telling you, I’m showing you. When I’m done telling you, I’m not showing you anymore.” Cognitive load time, the time it takes to “get” what you are looking at, is very quick, and continuing to display words or images long after their moment has past is deadening. Wordy, over-dense slides, he points out, are a legacy of print culture. The mind is quick, predisposed to fill in gaps, to create meaning and narrative from small, disparate pieces of visual information. This means that “visual rhetoric” can be very powerful. But we have not as yet figured out how that visual rhetoric can best be employed. This is one area he plans to explore in his future work.

Of the many fascinating points in his keynote speech about the techniques of visual communication and learning, one was a critique of the way presentation software is commonly used, with outline slides that statically reproduce a series of points that a speaker is making. McCloud’s active principal, brilliantly put into practice in his own show, is synchronization: “When I’m telling you, I’m showing you. When I’m done telling you, I’m not showing you anymore.” Cognitive load time, the time it takes to “get” what you are looking at, is very quick, and continuing to display words or images long after their moment has past is deadening. Wordy, over-dense slides, he points out, are a legacy of print culture. The mind is quick, predisposed to fill in gaps, to create meaning and narrative from small, disparate pieces of visual information. This means that “visual rhetoric” can be very powerful. But we have not as yet figured out how that visual rhetoric can best be employed. This is one area he plans to explore in his future work.

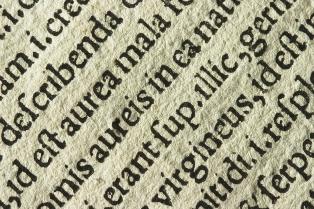

McCloud wants to figure out how to use visual culture, including comics but also the whole history of visual culture back to ancient Egyptian tomb paintings, Roman triumphal columns, and medieval stained glass windows, to try create the visual rhetoric of the web. His main interest is finding a way to make comics work effectively on the web, and he had many fascinating examples of innovative and effective web-based comics. His sense of joyous experimentation in search of the right use of the medium was very inspiring to me as I work on finding ways to use the web to enhance classical commentary.

One of his interesting observations regarding comics is that comic strips–3 or 4 panels– have transferred quite well to the web, but that long form graphic novels (think Persepolis and Maus) have not. In his view this is because people have an in-built desire for immersion, to lose themselves in fictional worlds, and that this is simply not readily possible on a computer screen. Books allow us that immersion, that forgetting of the medium known as the proscenium arch phenomenon, in a way that screens do not.

One of his interesting observations regarding comics is that comic strips–3 or 4 panels– have transferred quite well to the web, but that long form graphic novels (think Persepolis and Maus) have not. In his view this is because people have an in-built desire for immersion, to lose themselves in fictional worlds, and that this is simply not readily possible on a computer screen. Books allow us that immersion, that forgetting of the medium known as the proscenium arch phenomenon, in a way that screens do not.

Speaking of computer screens, McCloud was full of scorn for the preservation of upright rectangles of traditional comic pages in the digital realm. The sideways rectangle, wider than it is tall, is the more natural shape, based on the geometry of our two eyes. Theater stages and movie screens are shaped this way, as is the open print book—comics and web designers are foolish to ignore this, he says.

Another key point, and one quite relevant to the DCC, it seems to me, had to do with the relationship between text and image. “Form and content,” he said, “must never apologize for one another.” That is, to create an effective visual narrative, you have to believe both in the message and in the form. You can’t dress up a boring or lame content by adding pretty visuals, or it will just fall flat. By the same token, you shouldn’t simply add illustrations to a great text, because they will seem like afterthoughts, appendages. When creating graphic novels of existing stories the best ones (he singled out City of Glass, based on a Paul Auster story) are true adaptations that honor the potentialities both of visual art, and of the word. As we come to think at DCC of ways to use the visual to enhance the comprehension and enjoyment of Latin and Greek texts, all these reflections are highly relevant.

One more super cool idea I picked up: it is believed that there are six and only six primary facial expressions that express emotions across cultures: joy, surprise, fear, sadness, disgust, and anger. These can be combined: anger + joy = cruelty. A nifty piece of software called The Grimace Project allows the schematic mixing of these, a primitive analogue to the comic artist’s craft. Love, McCloud believes, is best conveyed by using a mixture of joy, surprise, and about 10% sadness–recognition that as wonderful as the emotion is, it is destined not to last. The Grimace Project, by the way, has been helpful to children on the Asperger’s specturm in learning about the visual expression of emotion and social cues.

McCloud’s 2005 TED talk may give you a flavor of what a treat it was to listen to him. Thank, Carleton (and the Mellon Foundation), for sponsoring a truly great conference. Future posts will provide details on some of the regular sessions.

–Chris Francese