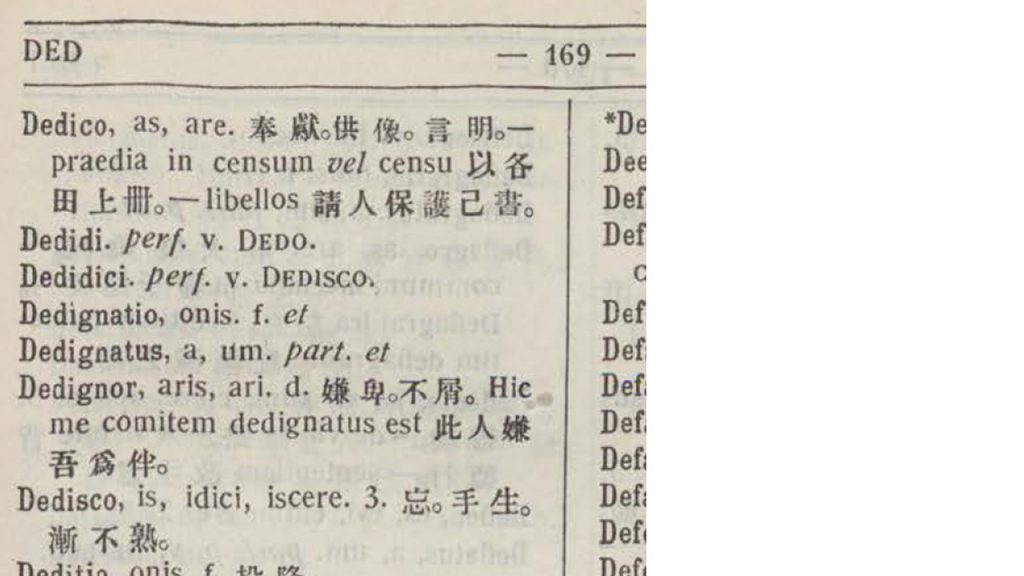

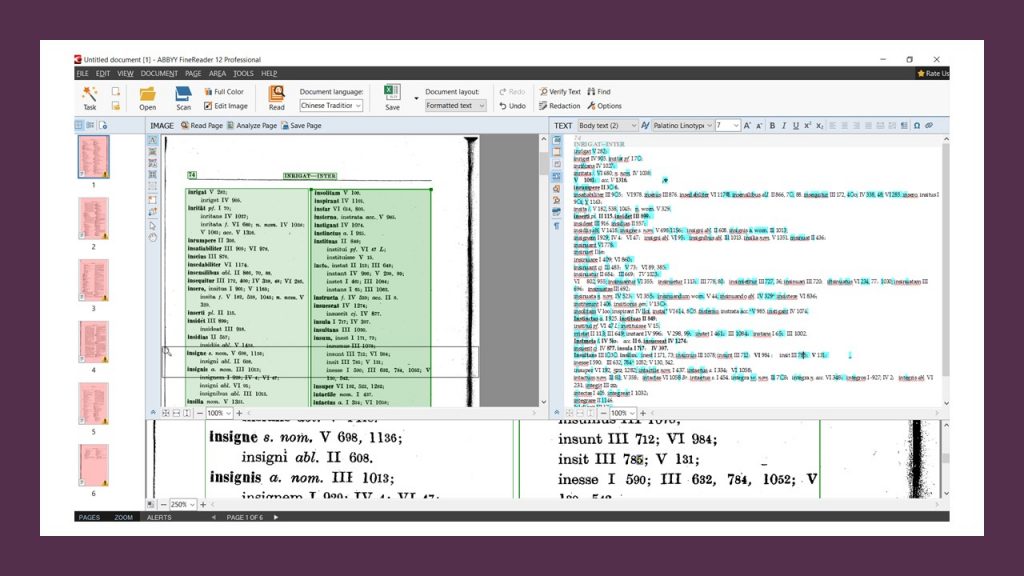

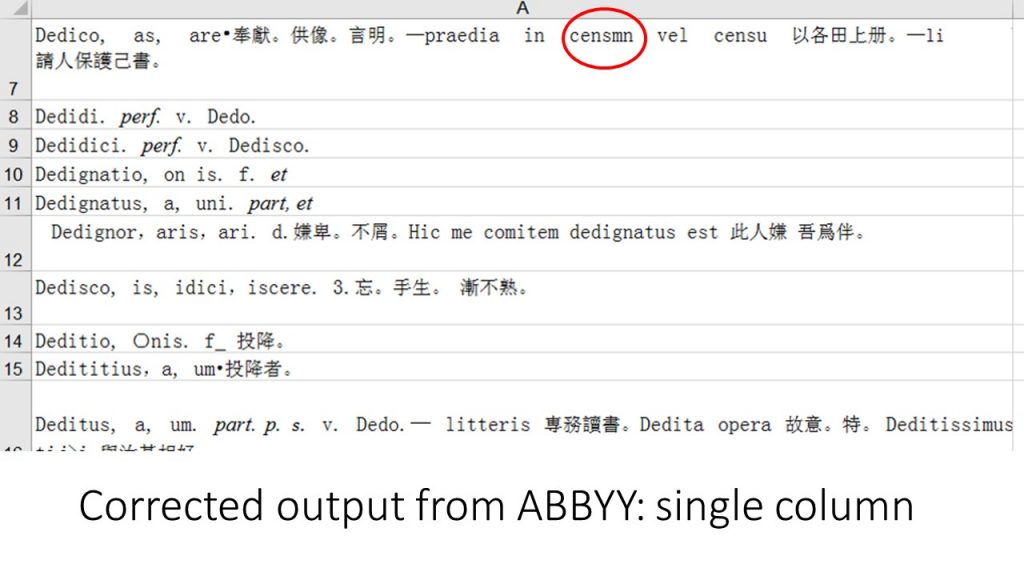

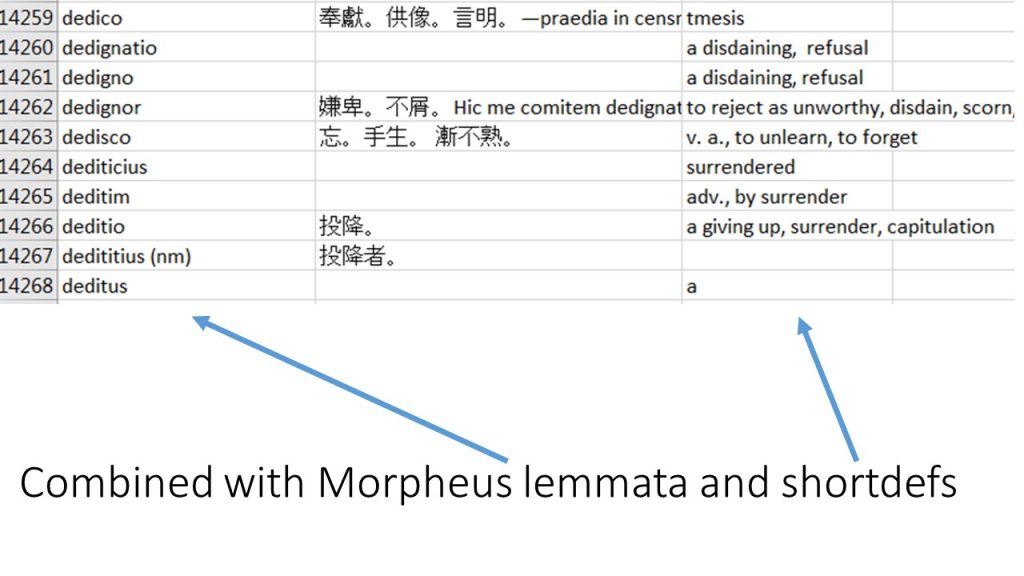

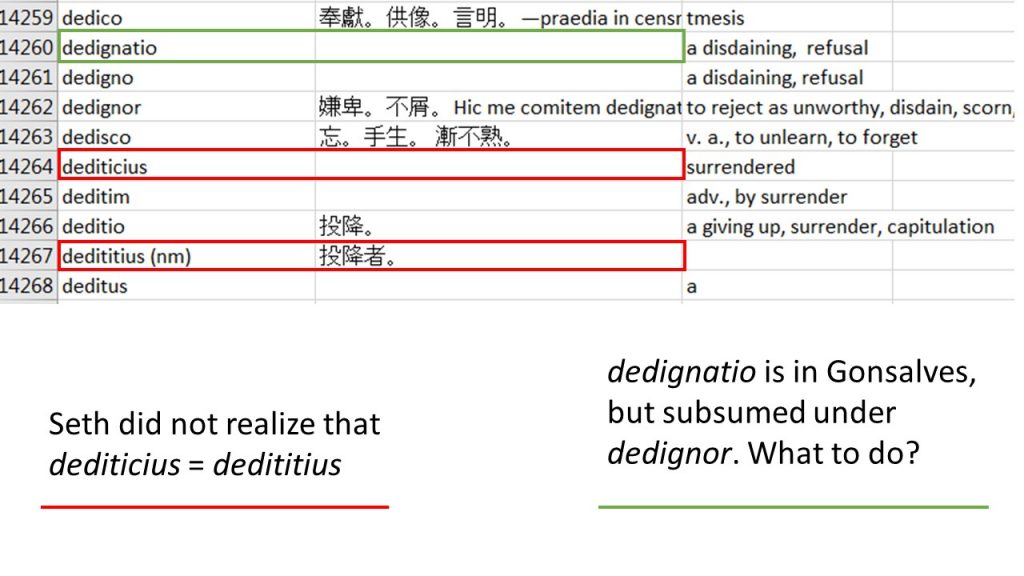

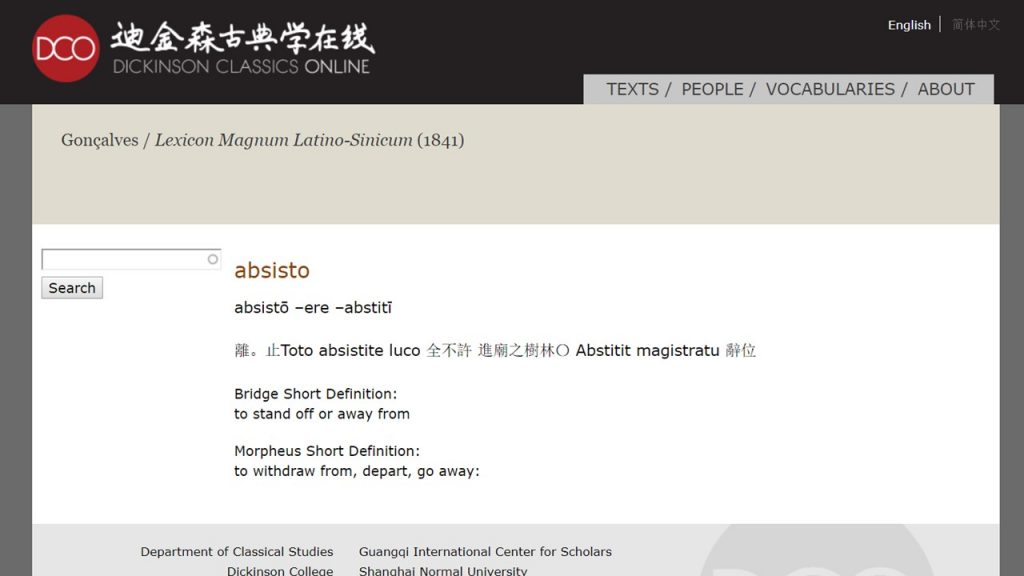

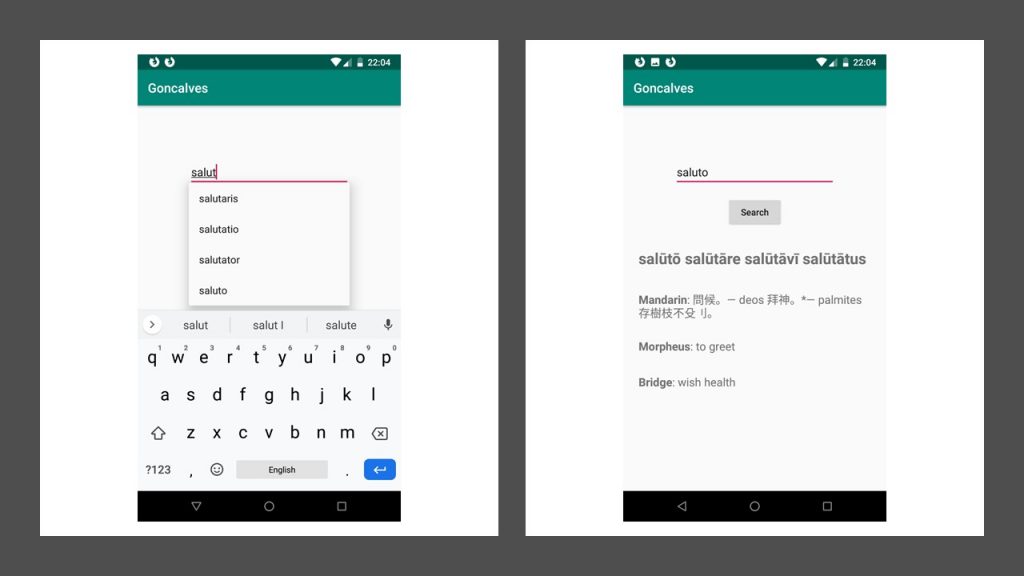

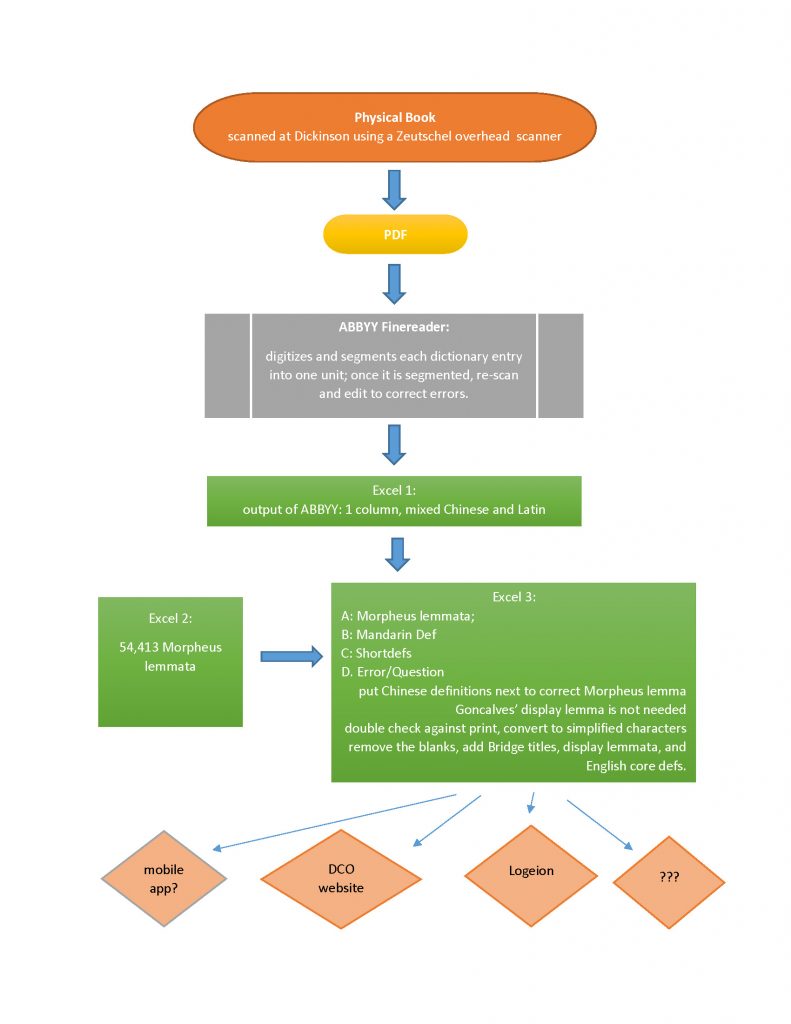

Latinitas Sinica: Journal of Latin Language and Culture is published in Hong Kong by Michele Ferrero as part of the activities of the Latinitas Sinica foundation, whose mission is the support of the learning and teaching of Latin Language in China. I was pleased to find in Issue 6, published in 2018, an article by Leopold Leeb, the distinguished Austrian Sinologist and professor at Renmin University in Beijing, called “Latin Tombstones in China and the History of Cultural Exchange” (pp. 41-106). It includes the epitaph of the Portuguese missionary and lexicographer Joachim Alphonse Gonçalves (1781-1841), who is close to my heart because I am overseeing a project to digitize his large Latin-Chinese dictionary. The goal of the project is to turn it into a mobile application and publish it on DCC’s sister site, Dickinson Classics Online, which is aimed at a Chinese-speaking audience. A group of students from Wyoming Seminary (an independent private school here in Pennsylvania) has recently come on to help in the editing of the data, supervised by their teacher Liz Pendland. I thought they in particular might like to learn a little more about the man behind the dictionary.

First, a bit of context from Prof. Leeb (p. 43):

The tombstones of Catholic missionaries were usually written in Latin. They are precious historical documents. Famous cemeteries are the ones in Beijing. In 1610,

after the death of Ricci, a piece of ground was given to the Church, located outside the Fuchengmen, the so-called „Tenggong Zhalan“滕公栅栏 (or “Chala“), where Ricci,

Schall, Verbiest and many others are buried. The cemetery was enlarged in 1654, but the French Jesuits (Bouvet, Regis and others) were buried at a new site after 1732,

namely at the Zhengfusi 正福寺, a few miles to the west. These cemeteries were destroyed in 1900, but restored thereafter. More than 800 missionaries had tombs and

steles at Zhalan, before the Zhalan area was confiscated and the tombs were ordered to be moved to Xibeiwang 西北汪, Beijing. However, many steles are lost, and only

63 have been preserved. These 63, among them the tomb-stones of Ricci, Schall, Verbiest, and Buglio, are still at Zhalan. The stones from Zhengfusi have been moved

to the Stone Museum at Wutasi 五塔寺. Other Catholic cemeteries are the Dafangjing 大方井 cemetery at Hangzhou 杭州, where Yang Tingyun’s 杨廷筠 son erected a

cemetery for the foreigners. In 1676, Fr. Intorcetta 殷 enlarged that cemetery. Aleni’s tomb is at the “Cross Mountain”“十字山”near Fuzhou. Jesuits from Shandong are

buried at Chenjialou 陈家楼, west of Ji’nan. Some Franciscans are buried at a cemetery near Linqing 临清 (here also della Chiesa’s tomb was found). At

Huangshakeng 黄沙坑, west of Canton, some Franciscan missionaries are buried. Bishop Luo Wenzao and some foreign missionaries were buried at Yuhuata 雨花台

outside the Jubao Gate 聚宝门 of Nanjing, but this cemetery was destroyed by the Taipings. Xu Guangqi 徐光启 has his tomb in a park at Xujiahui 徐家汇, Shanghai. The different mission societies had cemeteries in their respective areas of work.

And now, the Latin text of Goncalves’ tombstone, as edited and translated into English by Prof. Leeb:

D.O.M

HIC JACET REVER. D. JOAQUIMUS ALFONSUS GONSALVES LUSITANUS

PRESBYTER CONGREGATIONIS MISSIONIS ET IN REGALI SANCTI JOSEPHI

MACAONENSI

COLLEGIO PROFESSOR EXIMIUS REGALIS SOCIETATIS ASIATICAE

SOCIUS EXTER

PRO SINENSIBUS MISSIONIBUS SOLICITUS PERUTILIA OPERA SINICO

LUSITANO

LATINOQUE SERMONE COMPOSUIT ET IN LUCEM EDIDIT MORIBUS

SUAVISSIMIS DOCTRINA PRAESTANTI INTEGRA VITA QUI PLENUS

DIEBUS IN DOMINO QUIEVIT SEXAGENARIO

MAIOR QUINTO NONAS OCTOBRIS ANNO MDCCCXLI.

IN MEMORIAM TANTI VIRI EJUS AMICI LITTERATURAEQUE CULTORES

HUNC LAPIDEM CONSECRAVERE

[my emphasis]

“Here lies the Reverend Father Joachim Alphonsus Gonsalves, from Portugal, a priest

of the Congregation of the Missions professor in the royal College of St. Joseph in

Macao, also a member of the Royal Asiatic Society, who composed and published

many very useful works for the missions, works in the Chinese, Portuguese, and Latin

language. He was a very gentle teacher and a man of integrity, who died in the age of

65 and rests now in the Lord. He died on 9 October 1841. In the memory of such a

great man his friends and students have consecrated this stele.”

Leeb provides the following note:

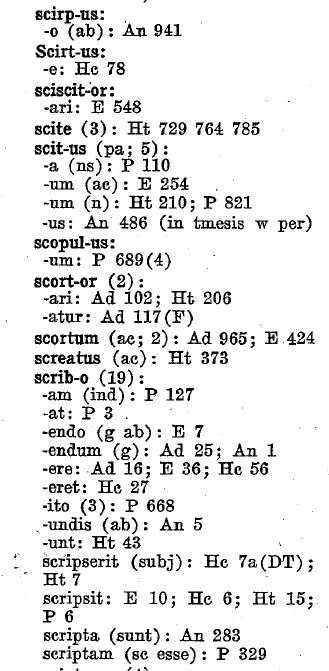

Gonsalves, Joachim Alphonse, CM 江沙维, 1781-1841, Portuguese Lazarist, who joined the Lazarist seminary in Rihafoles, Portugal, in 1799. In 1801 he professed vows, came to Macau in 1813. He was appointed to go to Beijing, but did not get permission, due to the strict policies of Jiaqing Emperor. He taught for many years at the Sao José (St. Joseph) Seminary in Macau, where he trained young priests. He became a linguist and encyclopedist and compiled at least six bilingual dictionaries, a Chinese-Portuguese Dictionary 《 汉 葡 字 典》 , a Vocabularium

Latino-Sinicum《拉汉辞汇》(1836), a Lexicon magnum Latino-Sinicum(《拉丁-汉 语大词典》 (1841) etc. He died 3 October 1841 in Macau. Since 1872 his tomb is in the church of the San Jose Seminary, where the tombstone inscription has been preserved.

As we work on bringing Goncalves’ perutila opera to a new generation, it is pleasing to read of a tangible memorial to his life. If you are interested in Latin in China, please check out Latinitas Sinica and their interesting journal!

We can accept a maximum number of 40 participants. Deadline for applications is May 1, 2020. The participation fee for each participant will be $400. The fee includes lodging in a single room in campus housing (and please note that lodging will be in a student residence near the site of the sessions), two meals (breakfast and lunch) per day, as well as the opening dinner, and a cookout at the Dickinson farm. Included in this price is also the facilities fee, which allows access to the gym, fitness center, and the library, as well as internet access. The $400 fee does not include the cost of dinners (except for the opening dinner and the cookout at the Dickinson farm), and does not include the cost of travel to and from the seminar. Dinners can easily be had at restaurants within walking distance from campus. Please keep in mind that the participation fee of $400, once it has been received by the seminar’s organizers, is not refundable. This is an administrative necessity.

We can accept a maximum number of 40 participants. Deadline for applications is May 1, 2020. The participation fee for each participant will be $400. The fee includes lodging in a single room in campus housing (and please note that lodging will be in a student residence near the site of the sessions), two meals (breakfast and lunch) per day, as well as the opening dinner, and a cookout at the Dickinson farm. Included in this price is also the facilities fee, which allows access to the gym, fitness center, and the library, as well as internet access. The $400 fee does not include the cost of dinners (except for the opening dinner and the cookout at the Dickinson farm), and does not include the cost of travel to and from the seminar. Dinners can easily be had at restaurants within walking distance from campus. Please keep in mind that the participation fee of $400, once it has been received by the seminar’s organizers, is not refundable. This is an administrative necessity.

After digitization by

After digitization by