I am excited to attend my first Kentucky Neo-Latin Conference this week, organized by the amazing Jennifer Tunberg and Laura Manning. The program does not seem to be freely available online, so I reproduce it here.

Thursday, April 18, 2024 – 9:10 a.m. to 10:50 a.m. Via Zoom

Latin and Scientific Discovery in Australia and Peru; Learning Latin in Mexico

Organized by: Jennifer Tunberg, University of Kentucky. Chaired by: Terence Tunberg, University of Kentucky

9:10–9:20 Welcoming Remarks

9:20–9:40

“Flora in the Antipodes: Baron Ferdinand von Mueller’s Fragmenta Phytographiae Australiae.” Peter James Dennistoun Bryant. Independent scholar, Conventicula Lexintoniensia

9:40–10:00

“A Medical Thesis by a Peruvian Mulatto Towards the End of the Colonial Period.” Angela Helmer (University of South Dakota)

10:00–10:20

“What if the earliest students of Latin in the Americas were… Aztecs? Indigenous Latin in early colonial Mexico.” Ambra Marzocchi (Brown University; University of Kentucky alumna)

10:20–10:50 Discussion

10:50–1:00 Pause

Thursday, April 18, 2024 – 1:00 p.m. to 3:20 p.m. via Zoom

Translation, Style, Censorship: 4 Neo–Latin Texts, ss. 16–18

Organized by: Laura Manning and Jennifer Tunberg, University of Kentucky. Chaired by: Milena Minkova, University of Kentucky

1:00–1:20

“Moro, Maumethanus, or both? Descriptions of Islamic believers in Archangelus Madrignanus’s Itinerarium.” Shruti Rajgopal (University College Cork, Ireland)

1:20–1:40

“Cleansing the Channels of Expression? The Early Prose Style of Bonaventure Baron (1610–1696)” Jason Harris (University College Cork, Ireland)

1:40–2:00 Discussion

2:00–2:20 Pause

2:20–2:40

“Quanto Elegantius, Tanto Difficilius: on the Latin of Jacobus Trigland III’s Diatribe de Secta Karæorum” Justin Mansfield. Independent Scholar

2:40–3:00

“Timui ne a censoribus italicis prohiberetur: An analysis of pre–publication censorial interventions in Gian Vittorio Rossi’s Pinacotheca” Jennifer Nelson (The Robbins Collection, UC Berkeley School of Law

3:00–3:20 Discussion

Friday, April 19, 2024 – 10:00 a.m. to 12:40 p.m. via Zoom

Empire and Colony in Europe and the New World: Four Neo–Latin Perspectives, ss. 16–18

Organized by: Julia Hernández and Laura Manning. Chaired by: Leni Ribeiro Leite (University of Kentucky)

10:00–10:20

“Luisa Sigea’s Syntra (1553): Framing Feminine Space at the “Hesperian” Margin of Empire.” Julia Hernández (New York University)

10:20–10:40

“Epic emulation of Vergil’s Georgics in Basílio da Gama’s Brasilienses Aurifodinae.” Dreykon Fernandes Nascimento (University of Espírito Santo)

10:40–11:00 Discussion

11:00–11:20 Pause

11:20–11:40

“Translating Anti–Imperial Dissent in Neo–Latin: Antonio de Guevara’s Horologium Principum.” Matthew Gorey (Wabash College)

11:40–12:00

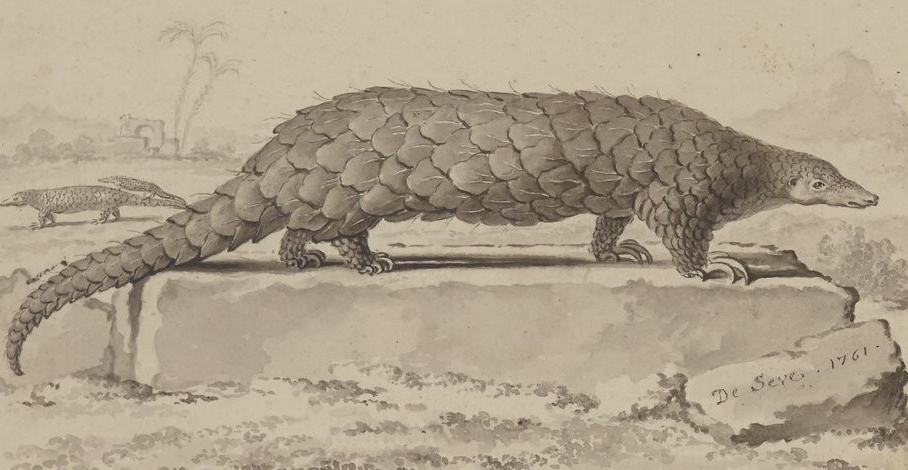

“Traveling to Lisbon: Maffei’s Historiae Indicae (1588) and the Portuguese Empire.” Christopher Francese (Dickinson College)

12:00–12:20 Discussion

12:20–12:40 Closing Remarks