Dec 2020

III. Kulturgeschichtliche Analysen: Hans or Hanuš Winterberg

Hans or Hanuš Winterberg:

Transatlantic Revival of a

German-Czech Composer

Anna Rosmus, Greater Baltimore, Maryland

In July 2018, a retired University of Kentucky professor addressed a crisis that had to be dealt with. “If we don’t liberate his music,” he quipped, “what will happen? The elements and insects may destroy the composer’s œuvre.”

Germans and Czechs in Czechoslovakia

Since the twelfth century, when Germans settled in the barren border regions of Bohemia, Czechs and Germans have been intertwined. Since 1620, however, the Habsburg Emperors pursued such an oppressive Germanization so that the Czech language all but vanished from state administration, literature, and schools.

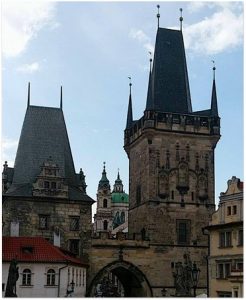

Prague, photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

In 1848, Prague had a German-speaking majority, but after the Czech National Revival began, that number fell. With the renaissance of language, Czech culture flourished. By 1910 only 37,000 residents (6.7%) were German-speaking.

When the Austro-Hungarian Empire lost World War I, an independent Czechoslovakia was created. Insisting on the historic borders of the Kingdom of Bohemia, instead of allowing ethnic borders, turned three million ethnic Germans into Czechoslovak citizens. The new Republic forbade terms such as Deutschböhmen (German Bohemians) and Deutschmährer (German Moravians) that were previously used. In that context, a distinct ethnic consciousness developed, and the unifying term “Sudeten German” was established.

In 1921, the country’s multi-ethnic population included 6.6 million Czechs, 3.2 million Germans, two million Slovaks, 0.7 million Hungarians, half a million Ruthenians, 300,000 Jews, and 100,000 Poles, as well as Roma and Croats. Whereas at least a partial knowledge of the “other” language was relatively common, Czechs and Germans continued to establish separate political, cultural, educational and even economic entities. Like many Czechs, Sudeten Germans used music to forge their identity.

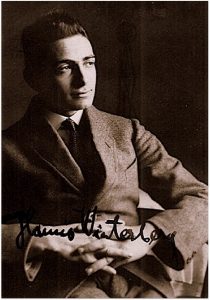

Jewish and artistically gifted 1921. Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

Hans Winterberg was born into a Jewish family in Prague on March 23, 1901. Adalbert Popper, his maternal grandfather, was a leather wholesale merchant. He and his wife, Agnes, had two daughters. Olga, the older, married Rudolf Winterberg from the Prague 2 municipal district, with whom she had two sons, Hans and Franz Winterberg. Irma, her younger sister, married Hugo Fröhlich in Rumburg, Bohemia, and gave birth to Edith. In Story 7 of an autobiographical account, Peter Kreitmeir writes that Hans Winterberg’s maternal great-grandparents co-owned Fröhlich & Winterberg, a fabric production company. At that time, Bohemia was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and like many Jews,[1] the family spoke German.

At the age of nine, Hans Winterberg, started taking music lessons from concert pianist Therese Wallerstein, a daughter of Moritz Wallerstein, chief cantor and choir conductor at the Maisel Synagoge. When Adalbert Popper passed away in 1917, he was buried at the Jewish Straschnitz (Strážiště) cemetery. An obituary listed among his closest relatives his siblings, Josef J. Popper, Jeanette Popper, Therese Neumann, and Charlotte Kurzweil in Budweis. Six years later, when his widow, Agnes, passed away, she was buried in the same cemetery.

At the German Academy of Music and Performing Arts in Prague, Winterberg studied composition with Fidelio F. Finke, a fellow Bohemian who also served as its rector from 1927 to 1945. At Neues Deutsches Theater, Winterberg studied with conductor Alexander Zemlinsky, a Jew from Vienna, Austria, who had converted to Christianity. At the Prague Conservatory, Winterberg studied with Alois Hába, who had previously worked in Vienna and Berlin, Germany.

At that time, both of Prague’s opera houses featured significant modernist productions.

As a young adult, Winterberg composed. He worked as a vocal coach and répétiteur in Brno[2] and Gablonz an der Neiße, as well as for other musical ensembles. Winterberg also painted.

Political tensions, however, increased. Among ethnic Germans, a rabid anti-Jewish propaganda rivaled anti-Slavic agitation, and Czechs responded with anti-German sentiments. If Winterberg, the German-speaking Jew, wanted to make a living in this explosive atmosphere, he had to adjust.

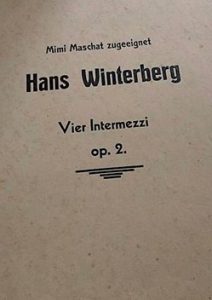

Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

In 1930, Winterberg married Maria Maschat,[3] a Roman Catholic. The census from that year lists him as “culturally Czech,” and according to Senior Researcher Michael Haas, PhD, at the Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst (Vienna University of Music and Performing Arts), all documents from that era were signed “Hanuš Winterberg.” That includes publicity photos, personal documents, correspondence and concert programs. In 1932, Winterberg’s father, Rudolf, passed away.

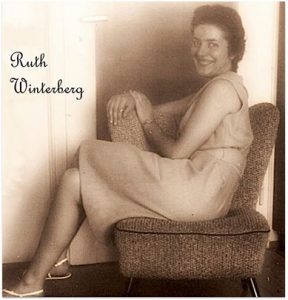

Three years later, daughter Ruth Christine was born. She was baptized as a Roman Catholic.

Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

Starting in 1933, when Hitler seized power in neighboring Germany, many modernist musicians chose exile in Prague. Temporarily, their arrival mollified Winterberg’s fragile position. He was less isolated.

After the Munich Agreement from September 1938, however, Germany annexed the Sudetenland. Josef Patzelt “Aryanized” the Rumburg fabric company. With the ensuing absorption of the country’s remaining “rump” in March 1939, Jews and Czechs suffered a brutal oppression. With modernist music and its Czech elements being suppressed, Winterberg’s options to earn a living were further reduced.

141,184 Jews were sent to Theresienstadt.[4] In July 1942, Olga Winterberg, née Popper, the composer’s mother, was one of them.[5]

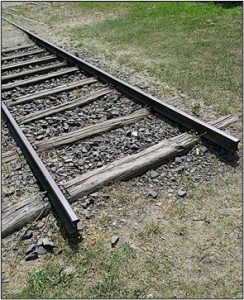

|

Railroad end at Theresienstadt/Terezín. |

Although so-called “mixed-race” marriages like that of Hans and Maria Winterberg were deemed “privileged”, political pressure mounted. In December 1944, Winterberg and his wife divorced, in accordance with the Nuremberg Laws. Their daughter, Ruth, was placed in a children’s home. As a precaution, Winterberg assigned his manuscripts to various persons, including his former wife.

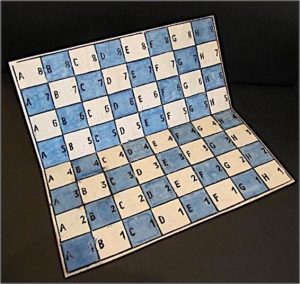

On January 26, 1945, Hans Winterberg was sent to Theresienstadt. When Soviet troops entered the Ghetto on May 9, 1945, only 16,832 Jewish inhabitants remained alive.[6] Winterberg was one of them. Among his meager belongings was a self-made chess board.

Photo Courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir Photo Courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

Seven decades later, the composer’s grandson, Peter Kreitmeir, would summarize, “The persecution through the National Socialists was a shattering experience that led to the collapse of the previous life, to ideological disorientation, to resignation and passivity.”[7]

Turmoil after WWII

Czechoslovakia suffered an estimated 345,000 WWII casualties. 277,000 of them were Jews. While Czechoslovak troops had fought in Poland, France, the United Kingdom, North Africa, the Middle East and the Soviet Union, an estimated 140,000 Soviet soldiers had died liberating Czechoslovakia.[8]

As combat ended, more than three million Sudeten Germans lived in Prague and in the border regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia. That amounted to approximately 23 percent of Czechoslovakia’s residents. Czechoslovakia was restored, and Hans Winterberg returned to his old apartment in Prague. His citizenship was reinstated.

Communities changed their German name (back) to a Czech version. The Bohemian town of Winterberg, for example, was now Vimperk. Even some composers adopted a Slavic spelling. Winterberg did not. He simply tried to continue his work. His once privileged “world”, however, seemed to turn upside down as well.

The country’s music shifted significantly. Not only had the exile and/or death of Czech musicians during the German occupation left their original ranks bereaved, but since then German culture was banned, and Soviet music favored. Political influence increased. The composers’ association encouraged political songs for the masses, and contacts with Western countries were censored.

Hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans fled, and the majority of those who initially planned to remain were expelled.[9] Most settled in Germany and Austria.[10] While those who had remained loyal to the First and/or Second Czechoslovak Republic were free to stay, like those subjugated by National Socialist terror, Winterberg’s brother, Franz Harry, settled down in Cologne, Germany. Hans Winterberg’s wife and daughter left for Munich, Germany, where Maria managed to find work as a composer, rehearsal pianist and active musician.

Hans Winterberg was not comfortable under such circumstances.

Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

Starting over as a refugee

A war-ravaged infrastructure on both sides of Germany’s border with Czechoslovakia made it very hard for the Allies and locals to efficiently address insufficient housing, depleted nutrition and other vital resources. Not only energy and food[11] had to be rationed. Bavaria faced a crisis.

Nonetheless, to retrieve his old manuscripts, Winterberg applied for a passport[12] in 1946.

In 1947, Winterberg travelled to Bavaria. After arriving at a refugee home in Riederau am Ammersee,[13] where Maria and their daughter, Ruth, had previously been stranded,[14] Winterberg desperately needed money. He applied for refugee status and obtained ID no. A 143/5444.[15]

Before long, the musician pursued opportunities in Munich, where he found work as an editor at Bayerischer Rundfunk (Radio Bavaria) and as a music instructor at the Richard Strauss Conservatory.

His young German student, Heidi Ehrengut, became his second wife. Once again, however, political change was underway. In May 1949, the western sectors, controlled by France, the United Kingdom, and the United States, merged to form the Bundesrepublik Deutschland (Federal Republic of Germany). In August, federal elections were held, and a shift toward the political and cultural right-wing reverberated.

Friedrich Edmund Rieger,[16] an ethnic German from Bohemia, took charge of the Münchner Philharmoniker (Munich Philharmonic).[17] Having replaced the US-appointed Hans Rosbaud, it hardly surprised anyone when he announced that the orchestra would all but eliminate modernist music from its program.[18]

For Hans Winterberg, living at the edge of society seemed inescapable. When an assembly ban for expellees was lifted in the late 1940s, Sudeten Germans founded not only choirs to feel socially and culturally more at home, but music was instrumentalized to shape personal as well as collective identities. Even dances and other musical gatherings often memorialized an idealized, lost homeland.

For Winterberg, that was a significant opportunity. Bayerischer Rundfunk, for example, recorded more than 20 hours of his music, with leading artists and ensembles. On November 13, 1950 his Konzert für Klavier und Orchester (Concert for Piano und Orchestra) premiered. On February 12, 1952, his Suite für Streichorchester followed.

Towards the end of 1954, the pianist Magda Rusy performed some of Winterberg’s piano works in Austria, Yugoslavia and other countries.[19] When Bayerischer Rundfunk first broadcast Sinfonia dramatica, his first symphony, it was performed by the Munich Philharmonic, and he referred to it as a premonition of the catastrophe of WWII.[20]

To get a foot into more doors, Winterberg joined the Künstlergilde Esslingen, an artists’ association with a focus on German heritage in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. He asked for financial assistance. On March 20, 1956 they inquired about biographical and professional details. One day later, Winterberg replied:

Born in Prague; there, completed middle school after basic school, then also music academy and state conservatory. After transitional activity at the theater, dedicated solely to composition and music theory. Emigrated [sic!] to Germany in 1947. There, already numerous performances of my works in various cities, publicly as well as broadcast by the radio. Information about me provides General Music Director, Fritz Rieger, in Munich, also Mister Willibald Götze, PhD, leader of the music department at Bayerischer Rundfunk in Munich.

To highlight his precarious situation, Winterberg wrote about his inability to pursue

“the important work on a piano extract … for I have no money for necessary music paper. … I obtain[ed] a charity fund of DM 150 a month from the Radio, and case-based smaller support. From that, I have to sustain my wife, and in addition partially my daughter from the first marriage. Although I am registered at the Munich housing office, I cannot co-pay construction costs. Also, the many trips to Munich, which I would need, I cannot finance, for as an independent coworker of Bayerischer Rundfunk I am not privileged to reduced tickets. On the other hand, from out here, it is all but impossible to maintain the necessary connections with the city.

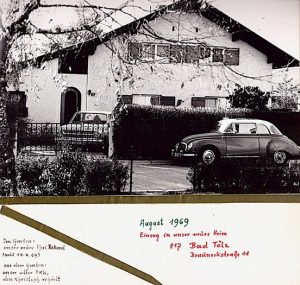

On June 13, 1956, the Munich Philharmonic played his Symphonischer Epilog. Eventually, Winterberg moved to Bad Tölz where he composed again.

Reinventing himself to blend in

While Catholicism, the Sudeten Germans’ preferred religion, was also prevalent in Bavaria, few were welcomed with open arms. Their dialects differed, as did their clothes, their food, and many customs. Mixing with local people often triggered ethnic slurs such as “Blutschande,” sexual relationships between people of the “Aryan” race and “inferior” others. Acceptance, even recognition for their music, frequently took decades. Their integration was as expensive as it was unpopular.[21]

On one hand, Winterberg confessed his belief in a “kind of bridge between the Western culture (that is also of the German) and that of the East” [European culture].[22] On the other hand, he seemed less uncomfortable among right-wing Germans than among left-leaning Czechs.

For a former Czech Jew, assimilation cannot have been easy. Winterberg had already learned to “go with the flow”. This time, he went to great length to avoid being “outed” as a Czech or a Jew. Now, he was known as Hans Winterberg.

When “accused of being a Czech”, Haas from the Vienna University of Music and Performing Arts described on June 6, 2018, Winterberg as “particularly evasive in correspondence” with Heinrich Simbriger, one of the founders of Sudetendeutsches Musikinstitut (SMI, Sudeten German Music Institute) in Regensburg. In a blog, we read,

“even in a letter…, in which Simbriger attempts to nail Winterberg’s true national colors, Winterberg skates about judiciously. Instead of offering a direct answer, … he squirms and explains that it was his father who filled in the census form in 1930; and rather than answering Simbriger’s suspicions, he replies with what he hopes will be accepted as rhetorical questions: ‘Didn’t you know that Alois Hába preferred to speak to me in German because my Czech was inadequate?’ … ‘Didn’t I only attend German speaking schools?’ ‘Should I be held responsible for how my father filled in the census form?’ ‘Have you ever heard me speak Czech?’ and so on.”

Over time, things improved. In Bavaria, where approximately one million Sudeten Germans were permanently settled, they were dubbed its “Vierter Stamm” (fourth tribe).[23] Mostly conservative politicians began to view them as potential voters, and in 1954, the Minister President announced the state’s patronage.

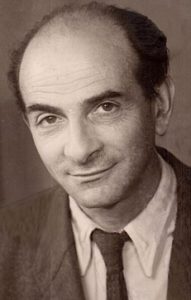

Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

At that time, Ruth,[24] Winterberg’s daughter from his first marriage, fell in love with a local, physically handicapped man, Adolf Kreitmeir. In “Story 6” of an autobiographical account, their son, Peter Raimund Kreitmeir, writes that his parents quickly married. Winterberg served as a witness. Five months after Peter was born, however, the couple divorced, and his then 25-year-old father obtained custody. Ruth was 19, and they hardly had any contact until she passed away in 2015.

According to Kreitmeir, his father, hardly mentioned Hans Winterberg, except for him being a “very fine man”, and a starving musician. “That he was a Jew, and born in Prague, my father did tell me as well, but to me, both always were very abstract.” Kreitmeir never met the composer.

In the meantime, Winterberg’s third marriage failed.

In 1968, when Winterberg wed Luise Maria, née Pfeifer, a Sudeten refugee from Tetschen-Bodenbach, her 22-year-old son, Christoph Alexander, no longer lived at home. He attended college in Munich, and Kreitmeir writes that his father was a Waffen SS soldier. Winterberg adopted Christoph anyway. According to Kreitmeir, Christoph was “a victim of the expulsion”, who “wandered through life completely intimidated.”

Over time, Winterberg’s fourth wife seems to have perceived Ruth, and possibly her mother, Maria, as a burden. In a message from July 2018, Kreitmeir reported that since the 1960s, his mother had no longer any contact to her father.

Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

Converging or disparate musical identities?

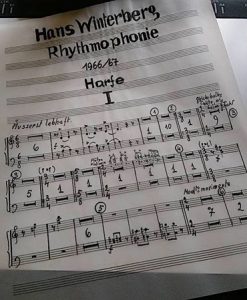

“As an artist,” Winterberg saw himself as a member of that “group of lopsided disadvantaged.”[25] He composed orchestral works, some chamber and piano solo works, music for radio plays as well as some vocal music. His compositions are almost exclusively instrumental. Some musicologists talk about the impact that Richard Wagner, Claude Debussy, Arnold Schönberg, Béla Bartók und Igor Strawinski had on Winterberg. While absorbing such elements, he is credited with developing his own style.

|

|

| Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

Although the right-wing Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft claimed to represent (all) German refugees and expellees from Czechoslovakia, its harsh political positions were too controversial for many—if not most—to associate with this organization. Sudetendeutscher Tag, their annual meeting at Pentecost weekend, however, still draws tens of thousands of participants.

Winterberg seems not to have been embarrassed. In 1963, he accepted a Sudetendeutscher Kulturpreis, although Kreitmeir points out that it was signed by Hans Christoph Seebohm, then spokesperson of Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft.

One year later, Winterberg was recognized at the annual Johann-Wenzel-Stamitz-Preis ceremony. Originally known as Ostdeutscher Musikpreis (East German Music Award), it is named after Johann Wenzel Anton Stamitz, a Christian composer and violinist from Bohemia, who immigrated to Germany, where he became widely known as founder of the Mannheim School. Recipients of the award are composers and other musicians whose work not only originates “in the reflection and in the exchange with German music in Eastern Europe,” but also demonstrates “affinity to the music of historically German cultural landscapes.”[26]

The life and work of Hans Winterberg appeared to have come full circle.

Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

The composer died on March 10, 1991 in Stepperg, Upper Bavaria. His fourth—and last—wife died 20 days later. Both were buried in Bad Tölz. There, grandson Peter quotes his father’s stepbrother, Christof, saying the priest saw no problem in providing a Catholic burial for Winterberg, whereas his colleague in Stepperg was unwilling to do that.

In 2000, Christoph presented the musical estate to the Sudeten-German Music Institute (SMI) and received 6,000 German Marks.[27]

Photo courtesy of Kreitmeir Photo courtesy of Kreitmeir |

In September 2002, Christoph also agreed to a contract[28] with SMI, which some perceived as an embargo[29] of Winterberg’s music. After Bayerischer Rundfunk broadcasted about that, Christoph and SMI agreed to void that contract in 2015. Since then, SMI was free to utilize that estate. Copyrights, however, were excluded.

Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

A goldsmith discovers his heritage

Peter Kreitmeir, a grandson of Winterberg, lives in Königsdorf. He works as a goldsmith in Murnau. After his wife divorced him, he began to look for his roots. In 2010, at the age of 55, he searched for his mother, Ruth. A parish newsletter, congratulating her on her 75th anniversary, listed her address. A one-time meeting, however, Kreitmeir recalls, lasted merely three minutes. She was not ready to address those “old issues.”

When surfing the internet for traces of his grandfather, Kreitmeir tripped over an entry from the Bad Tölz cemetery. Learning that the fee for Winterberg’s grave was up for renewal, he introduced himself via e-mail to the current caretaker as the composer’s grandson. A few days later, he recalls, the telephone rang. It was Christof, the composer’s adopted son. Relieved that a grandson was willing to take over these duties, the newly discovered uncle began to talk.

Kreitmeir also remembers his first written “encounter” with the late Hans Winterberg. Lexikon zur Deutschen Musikkultur, published by the Sudetendeutsches Musikinstitut in 2002, he writes, claimed that “based on his confession of [being a] Sudeten German, he remained interned” in Theresienstadt “by the Czechs after May, 8, 1945. In 1947, he was expelled.”

In publications of Bayerischer Rundfunk, such as the composer portrait from March 31, 1965 by Alfons Ott, later director of the Munich municipal library, Kreitmeir observed that reports were “exclusively about his musical work”. In the spring of 2014, Michaela Richstein, a daughter of Winterberg’s second wife, gave Kreitmeir the papers she owned. Seeing his grandfather’s legacy in Regensburg for the first time, where it filled 27 cartons, Kreitmeir recalls as beautiful, and as shocking as well.

Before long, the goldsmith proudly published an autobiography. “Story 6” addresses “My Grandfather, the Composer.” Kreitmeir also began visiting Prague and Brno in the Czech Republic, where Winterberg had lived, and he offered lectures. On Facebook, the grandson manages the page Hans Winterberg, as well as his own page, where he posts news about his ongoing personal journey. In 2017, for example, he was looking forward to scan “ca. 80 works on 8,000 pages of handwritten notes.”

|

Photo Courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

One of the oldest, Kreitmeir noted, was from 1928, and dedicated to his maternal grandmother, Maria Maschat.[30] When Christof passed away in February 2018, he left Kreitmeir the composer’s piano.

Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

Reassessing the musical estate

Today, the Oberpfalz district, funding provider of SMI, owns the Winterberg papers. According to a flyer, the institute’s obligations include exploring, documenting and promoting the music from Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia from the Middle Ages to our time. Publications and music events make its findings accessible. The district’s homepage openly highlights that the SMI focuses on residents with “German language, descent or nationality”, while playing a significant mediating role between German and Czech music.

Some feel that the Regensburg institute on Ludwig-Thoma-Street 14 is a logical location for the musical papers. After all, Winterberg had chosen to live in Bavaria since 1947, he had fraternized with Sudeten Germans, married a Sudeten German woman, and even pretended to be a Sudeten German. The fact that this institute is expanding its audience, and the state of Bavaria co-sponsors a new building to better house artifacts[31] further supports that thinking.

Kreitmeir himself is adamant about Winterberg NOT having been a Sudeten German, but a Czech composer instead. Nonetheless, in September 2015 he donated the Richstein estate to SMI. Andreas Wehrmeyer, PhD, at Sudetendeutsches Musikinstitut, however,[32] explained on July 18, 2018 that Kreitmeir’s invoking copyrights “resulted in certain opposing interests regarding the evaluation and printing of the Hans Winterberg estate, which to date could not be agreeably resolved.

Aside from that, the creative estate is openly accessible to interested researchers at the premises of the Oberpfalz district, without particular restrictions or obligations. Scans or copies of the material, however, can only be handed out with approval of Peter Kreitmeir. With this in mind, we have proceeded and also will proceed in the future. I am pleased about the interest in performances of works by Hans Winterberg, and I like to support all efforts concerning that.

In the meantime, Randy Schoenberg, grandson of the composer Arnold Schönberg, and a distant relative of Winterberg, put Kreitmeir in touch with Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst (University for Music and Performing Arts) in Vienna. Its institute exil.arte collects, maintains and disseminates works of composers, scholars and performers who fell victim to political persecution. Kreitmeir now wants Exil.arte to store and evaluate all Winterberg papers. Haas, an intended beneficiary, is chiming in.

Winterberg’s output is significant in its quantity, but also significant in its aesthetic qualities. Its undisguised exploitation of distinctive Czech characteristics, such as cross- and polyrhythms, along with invigorating musical energy would suggest why Simbriger and the Sudeten Germans found his music culturally and aesthetically questionable. His only work referencing the Sudetenland is called Sudeten Suite, and coincides with the start of his relationship with Luise-Maria Pfeifer. It is in contrast with the rest of his output, offering soft pastoralism and unapologetic, folksy sentimentality. [… This] can be understood as a combination of infatuation with Luise-Maria Pfeifer, a Sudeten German, and as camouflage to avoid further accusations from other displaced German Czechs.

Haas further claims:

Winterberg’s music is typical of Czech composers from the early and mid-20th century. It is built on aesthetic foundations that find their provenance in the music of Leoš Janáček: rhythms based on Czech speaking patterns .[…] The music is largely tonal, but also offers an expressive and galvanizing dissonance. It is more engaging than German ‘New Objectivity’ and more accessible than Viennese Serialism. … Though it appears that Winterberg was interested in composing an opera, vocal music would appear to be … the smallest genre in his total output. Chamber music in many configurations, as well as piano music, make up the largest amount of his total output, while his symphonic music is unquestionably his most impressive and representative work.

Thus, Haas ambitiously urges a relocation to his own facility in Austria:

The exil.arte Center … is embarking on publication partnerships with some of the world’s most important music publishing houses … and … is able to offer optimum, modern storage facilities for original manuscripts …. Even high-resolution scans cannot offer the same analytical benefits as access to the original. For the original to be accessible, it must be preserved under the best possible conditions. … Winterberg is a lone voice whose closest musical reference would be fellow Czech exile, Bohuslav Martinů. As such, Winterberg represents the continuation of a musical line that was almost entirely obliterated by Hitler.

Figuring out how to “liberate” the music

When Ulrike Präger, then a doctoral candidate in Ethnomusicology at Boston University, published a paper about Sudeten Germans and their music in 2011, she did not refer to Jews and voluntary emigrees such as Winterberg.[33] Misconceptions such as an alleged internment after Winterberg’s actual liberation by Soviet soldiers in May 1945, or him being an expellee,[34] are gradually corrected.

Interest in Winterberg’s music has also increased. Wikipedia features an interesting list of his works. Amazon sells his work. YouTube shows a video of the 2015 world premiere Suite Theresienstadt, 1945 in Italy. William Dietz from the Fred Fox School of Music of the University of Arizona announced: “I will be performing Winterberg’s Wind Quintet in Tucson, Arizona on October 16, 2016. The performance is part of an event titled “Forbidden Composers” and includes works by Schoenberg, Weill, and Winterberg.”

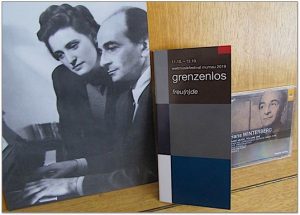

On March 12, 2017, Brigitte Helbig, a young pianist, played Winterberg in Munich. As part of the Prague Spring Festival, on May 15, 2018, at Saint Agnes, soprano Irena Troupová and Jan Dušek (piano) presented four songs by Hans Winterberg. On April 10, 2018, Kreitmeir was a guest at the Austrian (ORF) RadioCafé.

Hanna Arie-Gaifman, who runs music programs at the 92nd Street Y in NYC, became anxious. To support her, Kenneth S. Stern, then Executive Director of the Justus & Karin Rosenberg Foundation, sent out letters where he summarized, “There’s a Jewish composer who survived Theresienstadt, whose music she wants to see performed. … it would be great if you could help her figure out how to liberate the music.”

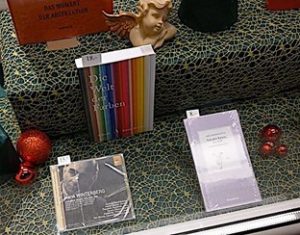

In September 2018, Toccata Classics in London released the first record with chamber music by Hans Winterberg. At a Weilheim music store, it became part of the Christmas selection.

|

Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

Towards the end of September 2019, when the Schwinghammer music store in Weilheim celebrated its 60th anniversary, Brigitte Helbig played Winterberg at the local city theater. In October 2019, borderless, the fabled Murnau music festival featured Brigitte Helbig playing Winterberg.

Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

A few days later, the Camerloher music school in Murnau introduced a CD with music for piano. When Weilheim music dealer Robert Schwinghammer arranged a piano evening, the Weilheimer Tagblatt headlined on October 15, 2019, “A Rediscovery at the Right Time”. The Murnauer Tagblatt from October 22nd titled: “Music that touches”, praising Helbig’s play of the 2nd Piano Sonata from 1941:

Under her hands, the sonata became a great fairytale with changing moods; intimidating, restless to subduedly serene. In the process, she made the music flow, let the grand piano bellowingly tremble, and lovingly whisper.”

In early November, commemorating the Night of Broken Glass in 1938, three musicians played Winterberg in Vienna. In late November, Irena Troupova and Jan Dušek performed Winterberg in Haifa, Israel. On December 9, 2019, at a fundraiser of the Brundibár Arts Festival[35] in Newcastle upon Tyne, a Winterberg suite for violin and piano was on the program. When the Exil.arte Zentrum in Vienna celebrated an expansion, Kreitmeir joyfully announced that his grandfather now has his own small memorial there. How exactly Winterberg’s music will be featured in the planned Munich Sudeten-German Museum, remains to be seen. Andreas Wehrmeyer from SMI in Regensburg stated on July 19, 2018, “I am not involved in the conceptional work…, but I do know that (in agreement with Peter Kreitmeir) Hans Winterberg is to be presented as a representative of classical music.”

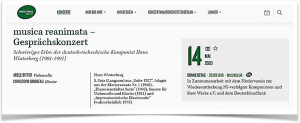

For May 14, 2020, Musica Reanimata announced a Berlin Concert Hall event, addressing the “difficult heritage.”

Photo courtesy of Peter Kreitmeir |

If handled properly, these new developments may not only help to provide a better understanding of an artist’s social and cultural isolation, of the far-reaching impact that political annexation and expulsion may have on a(ny) vulnerable individual, but also how music can reflect that. Giving listeners more opportunities to hear this music, might also loosen the composer’s old restraints.

Footnotes:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germans_in_Czechoslovakia_(1918–1938)

[2] Deutsches Bühnenjahrbuch 1929, p. 331.

[3] According to Haas, “Maschat was a former child prodigy, accomplished pianist and promising composer in her own right.” https://forbiddenmusic.org/2015/06/10/the-ominous-case-of-the-hans-winterberg-puzzle/.

[4] While about a quarter of the inmates (33,456) died in Theresienstadt, 88,202 others were deported to extermination camps. Only 2,418 either escaped or were released by the Germans in 1945.

[5] Born on March 3, 1878 she was sent to the Maly Trostenets death camp on August 4, 1942 and killed upon arrival. Various close relatives succumbed to a similar fate.

[6] https://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007323.

[7] http://kreitmeir.de/petersuchtmama/.

[8] Gleason, Abbott. A Companion to Russian History. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, p. 409.

[9] According to the Potsdam Conference, the formal transfer lasted from January until October 1946.

[10] In Austria, 130.000 were permanently accepted.

[11] From fall 1946 until March 1947, daily rations for a regular Bavarian, for example, had increased from 1,200 calories to 1,546. By the summer of 1947 only 1,085 calories were available anymore.

[12] In correspondence from the Ministry for School Education and Counterintelligence to the Ministry for Foreign Affairs we read: “The Ministry confirms that the composer Hans Winterberg wishes to travel abroad in order to search for his handwritten manuscripts, which he had sent to various European states before his departure to the Terezín concentration camp. On behalf of the Minister, it is thus recommended to hand the mentioned above a passport valid for all European states.” (Czech National Archives in Prague)

[13] Organizing all matters concerning refugees in Bavaria was the Bayerische Flüchtlingsverwaltung, directed by the Bayerischen Staatskommissar für das Flüchtlingswesen.

[14] In 1945/46, acceptance of refugees and expellees into the US-occupation zone usually occurred via Grenzdurchgangslager in Bayern (transit camps in Bavaria).

[15] Eligible for that and financial support from Lastenausgleich were ethnic Germans, who fled or were expelled.

[16] While Rieger’s explicit German roots resembled those of Winterberg, in 1934 the non-Jew had become deputy Kapellmeister (conductor of the orchestra) at Landestheater Prag, and two years later Kapellmeister of Deutsches Theater Prag. In 1938, Rieger was appointed musical chief director of the new Mělník radio station, and from 1939 until 1941, he directed operas at the Aussig municipal theater. By 1940, Bagatellen für Orchester, the first shellac records of Rieger and the Sudetendeutsche Philharmonics, were produced.

[17] Although the city, Bavaria and the Federal Republic decorated Rieger (Goldene Ehrenmünze in 1966, Bayerischer Verdienstorden in 1959, and Großes Verdienstkreuz in 1976), from 1971 until 1972 he directed the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in Australia.

[18] Monod, David. “Americanizing the Patron State? Government and Music under American Occupation, 1945-1953”. In Riethmüller, Albrecht. Deutsche Leitkultur Musik: Zur Musikgeschichte nach dem Holocaust. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2006, p. 56.

[19] Schwäbische Landeszeitung Augsburg, August 29, 1955.

[20] Schwäbische Landeszeitung Augsburg, August 29, 1955.

[21] https://www.welt.de/geschichte/zweiter-weltkrieg/article147487793/Die-Flüchtlinge-müssen-hinausgeworfen-werden.html.

[22] Thomas Stolle, Hans Winterberg, 1991

[23] The historical ones are: Old Bavaria (Upper Bavaria, Lower Bavaria, Upper Palatinate), Swabia, and Franconia.

[24] Ruth, the daughter of Maria Maschat and Hanuš Winterberg, married in 1955, and had a son named Peter. According to Haas, “The traumas of her parents’ politically motivated divorce, her forcible placement in a children’s home and the subsequent deportation from her homeland left Ruth severely vulnerable and mentally damaged at a time when little help was available. Only four months after giving birth to Peter, she abandoned both husband and child. … Ruth seems to have been unable to hold on to either relationships or employment.”

[25] Note from December 6, 1963 to composer Alois Melichar in the Melichar estate at Monacensia, a Munich library.

[26] http://www.miz.org/details_8725_572.html

[27] According to Kreitmeir, Christoph told him, that he needed that money to recover the costs for the funeral.

[28] Conditions stipulated any and all access to those papers until December 31, 2020, unless Christof had agreed. Requests from living relatives were to be denied until December 31, 2050. After the expiration date, Winterberg was to be performed as a Sudeten German composer. Another condition was to actively suppress his Jewish origin.

[29] According to Haas, “It can be understood that the embargo imposed by the Sudeten German Music Institute on information regarding Winterberg’s estate or the embargo on information on his family, was an attempt deliberately to exclude petitions made against the estate by Ruth Winterberg, Maria Maschat or any other blood relative.”

[30] In July 2018, Kreitmeir stated about Maria Maschat, “About her, I know next to nothing, but [I] have some recordings of her from Bayerischer Rundfunk.”

[31] Currently, some criticize how the documents are stored. Haas stated, “all scores, manuscripts and documentation are held upright in uniform sized boxes. Manuscripts that are too large are simply ‘made to fit’; smaller documents are left to slide about without protection. Storage is in rooms that do not meet the standard archive requirements of heat, humidity or light control. Manuscripts remain vulnerable to elements as well as insects. Upright storage further damages the robustness of manuscripts, resulting in bends, folds and fraying at the sides. Itemizing of contents of each box has been haphazard with items listed incorrectly or left out.”

[32] In 2017, Christof transferred all rights to Kreitmeir, and passed away in 2018.

[33] https://www.ethnomusicologyreview.ucla.edu/journal/volume/16/piece/458.

[34] Kreitmeir points out that “Heinrich Simbriger, who established the Künstlergilde music archive, today Sudetendeutsches Musikarchiv, repeatedly published about Winterberg: ‘In spite of that, when one liberated him from the camp Theresienstadt in 1945, he did not hesitate a moment to profess his being a German, and thus to burden himself with the fate of expulsion from the old homeland. He was expatriated to Bavaria. (From: ‘Der Komponist Hans Winterberg’, [in] Sudetendeutscher Kulturalmanach V).”

[35] Performances by children of the Theresienstadt concentration camp in occupied Czechoslovakia made Brundibár, a Czech children’s opera from 1938, famous.