As a political period in the history of British royalty, the British Regency began when King George III was declared unfit to rule in 1811. During the Regency, King George III’s son held the powers of the King, until he was crowned King George IV after his father’s death in 1819. However, art historians oft define the Regency as beginning in 1789, the start of the French Revolution. Throughout the French Revolution, ideals such as nationalism were promoted through paintings and portraits which glorified famous battles and military leaders such as Napoleon Bonaparte. But how did these aesthetic changes affect portraiture in non-Revolutionary Britain?

Picture courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw03241/Thomas-Hope?LinkID=…, by Sir William Beechey

This portrait of Thomas Hope was painted by Sir William Beechey and first exhibited in 1799. Thomas Hope was born in 1769 into a Dutch merchant family, and his personal interests show a marked interest in foriegn culture. He travelled extensively throughout the Near East, including what is now Turkey and Syria.

In this portrait, Hope is dressed in clothing that was customarily worn throughout the Ottoman lands, but not in Western Europe. Interestingly, it is noted in the exhibit that Hope coined the phrase “interior design”, and this portrait was commissioned in order to be placed into his home, which also served as an exhibition for his design ideas.

This portrait serves to exalt the oriental aesthetics that Hope used in his own designs, and to portray a cosmopolitanism that was in fashion during this time of expanding world commerce. It is also important to note that as European colonial powers such as Britain and France increased their influence in lands such as Egypt during the Napoleonic era, interest in exotic products that were produced by these cultures also increased.

Categories: 2010 Tyler · Museums

September 8, 2010 · 1 Comment

Today, I visited The Sir John Soane Museum, which I must say is not your typical museum. It is located in the building that its architect namesake built especially to house his collection of priceless artifacts in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. Like many museums of the time, the owner’s philosophy for museum organization was basically to just cover the entire building in artifacts. The current museum staff has put a lot of effort into maintaining this philosophy, for better or for worse. Unfortunately, no picture can do the museum justice (which sounds better than just saying that the museum doesn’t allow pictures, which is an assumption that I made, not a fact), so you’ll have to go to the museum yourself to realize exactly how overwhelming it is. Every surface is covered in pieces from everywhere from Ancient Egypt and Greece through the Middle Ages. While this method of displaying art has historical value and is a good way of showing a lot in a small space, I’m not sure I’m a fan of it. Not only is it overwhelming, but it doesn’t do the art justice. All over the place are pieces that would normally be by themselves in a case, like the sarcophagus of Seti I, one of Egypt’s early princes. Instead, they’re all jumbled together, which makes it hard to appreciate them. Also, the way in which some pieces were displayed, especially ancient clay pots placed around the mezzanine between the ground floor and the basement, was clearly very unsafe, if preservation of the art is the goal, which it should be. It would be far too easy to destroy a priceless piece of pottery just by accidentally bumping it on your way past. A painting displayed in direct sunlight also comes to mind as a piece displayed in a unsustainable way. It’s interesting to compare the Soane Museum to other museums that we have visited in London, because most museums take very good care of their art, locking it in temperature-controlled glass cases. One of the few things I like about the Soane’s method is that it’s very easy to relate to the art because you can actually feel it if you want to (since there were no signs saying “Do Not Touch”, though that does not mean that I touched anything, because I understand basic preservation techniques) and it’s right in front of you. Either way, I believe the museum was a very good learning experience, and would recommend it to anyone visiting London.

Categories: 2010 MatthewM · Museums

Tagged: Soane

On Sunday I journeyed with Sarah and Emily down to Oxford Street to replace my sorely missed Swatch. I remembered passing the Swatch store on the Number 10 bus to Royal Albert Hall. (Incidentally, Royal Albert Hall was where my watch went missing.) With part of the Central Line closed for maintenance, we decided to take the same bus again. It dropped us off right outside the Swatch store and I quickly found a new watch I really liked. I was planning to post a picture of me wearing it with this blog, but one of the links broke today when I took it off to go through the metal detector at the Hindu Temple and I currently cannot wear it. The city of London apparently does not want me to ever know what time it is. Fortunately, Swatches come with a two year warranty, and I will get it fixed as soon as I get the chance.

We decided to explore some more of the shops on Oxford Street that afternoon. There were some stores that I had not heard of in the U.S. and some that I had. First, we went into Top Shop, a new store for me. They do operate in the U.S., although it is a British chain, I had just never seen one. The clothes were similar to what we would see at H&M or Forever 21, but significantly pricier. Next, we went into H&M, a store I am familiar with in the U.S., although they are based in Sweden. Although I am familiar with the store, the selection of clothing here was very different from what I am used to seeing in the U.S. The most striking difference was the lack of color. Where in the U.S. you can buy sweaters in a range of colors from bright red to royal purple, everything here seemed to come in the practical, muted colors of white, black, grey, beige, occasionally salmon or olive. It seems that this must be reflecting the English preference for modesty, privacy, and stoicism mentioned by Fox. Perhaps the English feel that wearing bright colors would draw attention to themselves in public, compromising their method of denying that they or the people surrounding them exist outside the privacy of their homes. Wearing bright colors may also indicate earnestness, trying too hard, or taking oneself too seriously. The Importance of Not Being Earnest is a cardinal rule, according to Fox. I reviewed Fox’s chapter on dress codes, but I did not find it very helpful for understanding this; she mostly talks about street sub-cultures and determining class from dress. She does say that the English have little style sense plus a lot of anxiety about dressing appropriately. Perhaps they just sell muted colors to make it easier on themselves.

Another store we ventured into was Primark. This store was not mentioned in Fox, but it seemed to us like it was the English equivalent of a Wal-Mart, with tables of plain t-shirts and sweaters for 3 or 5 pounds apiece and five pairs of fake pearl earrings for a pound. The scene in there though, did not allow us much space or time to think about class. People were dragging around huge mesh Primark bags and just piling clothes and towels into them, taking handfuls of jewelry and socks. It was unlike any scene I have ever seen in Wal-Marts in the U.S. It was insane. There were 10-12 cash registers in each department, with the queues winding their way through the whole departments. Let’s just say that if I ever go back to Oxford Street, it will not be on a Sunday, but a weekday at, say, 10 am. Reflecting though, it seems that Primark might be the type of store that English lower classes shop out of necessity, upper classes shop in so they can show off their “great deals” and that the middle classes wouldn’t be caught dead in.

We felt just a little bit guilty at first going shopping on Oxford Street instead of visiting a museum or a park, but it turned out to be quite a London learning experience, and definitely something to blog about.

Categories: 2010 Kaitlin

Tagged: Kate Fox, Oxford Street, Primark, shopping, Swatch

September 7, 2010 · 1 Comment

As most of the group made their plans to attend Notting Hill Carnival, I was feeling a little tired of crowds. I like cities, but in moderation, and after about a week in London I did not feel up to spending an afternoon shoulder to shoulder with complete strangers. So I decided to go over to the Tate Modern, which I had been curious about since our arrival.

The Tate was a mixed experience. I enjoy certain modern art, but usually only when it portrays something relatively concrete, and when I can still see the artist’s method. I love looking at post-impressionist art from the beginning of the twentieth century, but I feel less inspired when it comes to newer “modern” art. So I had trouble connecting with the majority of what the Tate had on display, which fell into a more abstract category. Still, the museum managed to hold my attention throughout, partially, I think, because of the layout: I never knew what I would find in the next room.

When I was nearly ready to leave the museum, I walked out into the hallway between the exhibits, in which big glass windows overlook a central lobby area. Visitors were gathered around the windows, looking down at something. I found an opening between the masses of onlookers, and down through the window myself. I saw that the floor of an enormous space in the lobby that had been empty earlier in the afternoon was now covered in black and white shapes, arranged like an abstract painting.

I went downstairs and made my way through the crowd to get a better view. I discovered that the installation was actually an enormous stage for a modern dance performance, and I was lucky enough to find a seat near the perimeter. Upwards of fifty dancers moved across the stage dressed in black and white, to expertly blended electronic and rock music. I noticed however that while the dancers who were featured were clearly professionally trained, and mesmerizing to watch (one stood on her head with only one hand on a ballet barre for support while moving her feet through the air perfectly in time to the music), others who moved in large groups performed only simple dance steps.

I later looked up the performance on the Tate Modern’s website to learn more. I found out that Michael Clark, the choreographer included seventy-five non-dancers in the performance (while also including his dance company- responsible for the acrobatics). This explained the disparity in skill level within the performance, but I still marvel at how small an impression that disparity made on me at the time. The parts of the dance that included the non-dancers were beautiful because of the sheer number of individuals moving in unison, so I was able to gloss over (I guess as Clark intended) any roughness in the individual dancers’ movement.

I still question however, why Clark would make the effort to train non-dancers, when more dancers (who I assume he could find) could have performed the same piece with greater grace and fewer rehearsals. I guess the aims of modern art and explains how the dance performance fits with the Tate Modern’s collection. Modern art consistently challenges whatever conventions come before. When we look at works of art in the Tate Modern, we ask ourselves (among other questions like, what’s a black square on a canvas doing in a museum?) whether the ideas behind them are original. So following a long tradition of ‘challenging,’ Clark challenged the convention that only highly trained dancers should perform in a large scale, professional level performance. There’s nothing more modern than that.

Dance Performance (personal photo)

Categories: 2010 Emily · Uncategorized

Tagged: Modern Dance, Tate Modern

September 7, 2010 · 1 Comment

… So far.

During the two weeks in London, I have so far had the opportunity to see a variety of shows, which have offered different perspectives of theatre culture in England.

First, there was The Merry Wives of Windsor at The Globe. As a groundling after a long day exploring the city, my feet were exhausted by my excitement levels were through the sky (well, higher than usual, as they tend to be at somewhat extreme heights in general). Seeing Shakespeare performed at The Globe was an incredible experience for many reasons. Not only was the performance one of the best live productions that I have seen, the theatre’s atmosphere was almost indescribable. It was almost if everyone had traveled to the turn of the 17th century. Usually, everyone is quiet during the performance and politely respectful of the performers. While this was the case, the audience seemed more willing to shout, cheer, and laugh uncontrollably at the events on stage. Being so close to the stage, the magic of the actors radiated from the stage and created an atmosphere unmatched by any performance thus far. The added music also added to the atmosphere- an Early Modern theatrical experience would have had the pre-show performers and would have been completely different from what we are used to. The performance was as close to replicating that experience as possible in our modern world. Afterwards, we were able to thank some of the actors and they seemed sincerely grateful that we said something- an idea that would be challenged later.

Next came the Proms at Royal Albert Hall. While The Globe was magical, Proms was one of the most equalizing of the performances because of how accessible they were. In the States, every classical concert I have been to has been a stuffy affair. There, the celebration of the music was open and everyone seemed to be unified in their desire for good music (which the audience should not have been disappointed with). The biggest issue I had with the Proms was the incessant coughing. Usually people try to hold their coughs, but when one or two people cough at during movements, it doesn’t provide an excuse for everyone to cough uncontrollably to prove they can and that they are not going to do disrespect the musicians by coughing during the performance. I would like to go back to Proms to see if it is a bizarre tradition or if that night was a fluke.

Royal Albert Hall

My following experience was Billy Elliot, which I have already blogged about, so I’ll try not to be redundant here. Other than being my first big West End experience, it was also important because it showed a lot of the themes of our course in a new light. Instead of applying the themes to the immigrant communities, it showed the themes in terms of a distinctively native English story. Furthermore, it also highlighted two differences between English and American theatre in particular. Firstly, we aren’t used to paying for our programs in the States. As an avid theatre goer, I’m used to being handed a Playbill (or regional equivalent) and continuing into the theatre. I don’t have to wonder who the cute guy playing a certain character is or why so and so looks so familiar. I don’t mind paying an extra three quid when I’m paying half of what I’m used to paying, but it definitely caught me off guard. Secondly, the tradition of stage door here is (as far as I’ve gathered) practically non-existent. In NYC, it is fairly common to wait after the show at the stage door to thank the actors for their performance, get an autograph, and if you are lucky, a photograph. (Yes, this can be a weird experience, but it can also be a great one.) When we went after Billy, it was completely different. While there were people there, the actors went by ignoring everyone. After Holly mentioned it, I realized that this was indeed a representation of the English concern for privacy and social dis-ease. On stage, the actors are free from interacting with the strangers feet away from them. At the door, they are in a different type of spotlight. Yet, the boundaries between personal and private life would not intersect. They are still technically at work. The guys from The Globe seemed to enjoy that we acknowledged them. I can’t wait to try another stage door experience to see the difference. (I planned to try again after Les Mis, but it was raining…)

The Victoria Palace, Home of Billy Elliot

Next came Bedlam, back at The Globe. For the first play by a woman performed there, the show was interesting. I’d like to say it succeeded it my expectations (which weren’t that high), but it didn’t. It did meet them, but something about the show was lacking the magic of the first show we saw there. At the end of the first act, I wasn’t at all satisfied, but by the end of the second, it had redeemed itself. I’d like to blame this all on not being a groundling and therefore surrounded by the audience members and the actors. I did enjoy it but it was not my favorite by any stretch.

The Globe, A View From Above

Lastly (thus far) is Les Miserables. One of my favorite musicals, I thoroughly enjoyed it. Despite the fact Marius has a slight bald patch, the actors were outstanding. (Even Norm Lewis, who I have seen in another musical and was THOROUGHLY disappointed in then, was outstanding. His awkward- but commanding- stage presence was perfect for Javert.) A truly equalizing musical, I was not surprised to see people in blue jeans and others in formal dresses. The difference is interesting when considered in the context of the musical and its equalizing themes. Theatre in London is truly for everyone- no matter one’s status. Seeing the opposites in dress at this show hit me as strangely appropriate. (I don’t want to elaborate knowing that some of you guys have yet to see it. So, I’ll just leave it at that.)

So far, I’ve thoroughly enjoyed my experiences at the theatre and can’t wait for more. I’m hoping to see Wicked (my favorite, in case you have missed that slight detail) and Blood Brothers at the very least. While technically not theatrical, I also expect my experiences at the various football matches I’m planning on going to to be worthy of a theatre stage!

Categories: 2010 Stephenie · Theatre

Tagged: "Billy Elliot", Bedlam, Les Mis, Merry Wives of Windsor, Playbill, programs, Proms, Royal Albert Hall, The Globe, Theatre, West End

Kate Fox told us that “the Church of England is the least religious church on earth” (354). I didn’t really understand how any organized church could fail to be religious until our visit to Westminster Abbey.

I mean, it’s incredible that most important aspects of English history and culture have fit into one beautiful building, dead bodies and all, from martyrs to scientists to poets to monarchs to the Unknown Warrior (which, just to say it, is the most beautiful monument I’ve ever seen). I’m impressed by Westminster Abbey. But I’ve never felt God more minimized. Other than a bland and generic “prayer” every once in a while, and the odd miniature stone saint or cross, the focus of Westminster Abbey is much more King and Country than God. I always thought Church of England was another way of saying Church in England; nope, this Church really is all about worshipping itself. Westminster Abbey is ground hallowed by history and culture, art and architecture, not by faith. I see why England wants to share this heritage with the world, but make no mistake about it – their concern is preservation of culture, not preservation of faith.

Westminster Abbey. Beautiful? Yes. Reverent? No. (personal photo)

You might respond to this criticism by saying that without opening the Abbey as a tourist attraction, we’d be denying visitors an important experience in English culture. You might also say that if the Abbey wasn’t so accessible to tourists, it would be difficult to raise the funds to keep it open and maintained at all (this may apply less to Westminster and more to other churches and cathedrals around England – Bath Abbey, for example, or Southwark Cathedral, which are less centrally located and famous).

Bath Abbey (personal photo)

I understand those points, but I have to wonder if, in this case, the chicken or the egg came first. Would parishoners be more prone to attend church as serious worshippers if the site wasn’t so wholly reduced to a tourist attraction or a history museum? I’m not an anthropologist or a religion major, but I don’t see how people can be expected to take their faith seriously if the church to which they belong doesn’t even take it seriously. Religion is part of culture, but to believers it’s much, much more than culture alone. To a believer, faith in God is literally a matter of life and death (and afterlife) in ways that food, clothing, music, and other aspects of culture can never be. The Church of England doesn’t seem to make any demands on visitors to its hallowed places – Bath and Westminster Abbeys spring to mind. (Any demands, that is, except incessant reminders that donations would be welcome.)

I’d like to contrast the Christian cathedrals we’ve seen so far with our visit to the Hindu temple today. This temple welcomes interfaith visitors, but only on its own terms, with the understanding that preservation of the Hindu faith and reverence for God are a prerequisite. The result was a moving religious ceremony to which I think we were all attentive, and a deeply reverent tribute to the Hindu faith, culture and history in the exhibition hall. I think if the temple let tourists wander in and out freely, messing with their audio guides, joking around, texting, taking pictures of the ceremony, what have you, the Hindu temple would be reduced to a cultural tourist attraction to check off a list rather than a spiritual experience. Also significantly, tourists like ourselves would feel like outsiders peeking in on someone else’s faith. Today, I felt like I was actively participating in a faith community. I felt like an insider rather than a voyeur. I think preserving this sense of reverence works out for the best for both visitors and believers, and I’d like to see more of it from the Church of England.

Categories: 2010 MaryKate · Churches and Cathedrals

While visiting the museums of London over the last two weeks, I’ve noticed that several of them seem to have only been opened for the purpose of showing off how powerful the British Empire was at its height. This is especially pronounced at the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. While I’m normally not much of a fan of imperialism, or any act of a bigger country dominating a little country, both of these museums have made me start to appreciate British Imperialism much more.

Let’s start with the British Museum. The British Museum may be seen by outsiders as a huge building filled with artifacts that the British stole from all the places they conquered. This isn’t completely true… Some of the pieces were stolen from countries that were never part of the Empire. In fact, there have been high-profile claims on British Museum artifacts from countries on four of the seven continents. The most notable claims are on the Rosetta Stone (which is their coolest artifact, in my opinion) and the Elgin Marbles, which are parts of the Athenian Parthenon. Luckily for London tourists, in 1963, Parliament passed the British Museum Act of 1963, which prevents any object from leaving the museum’s collection once it has entered it. This allows the British Museum to continue to be a concentration point for really cool artifacts, like original Roman letters, the Rosetta Stone, and parts of many ancient structures. On the flip side, I understand why countries would want their artifacts back. It’s their history, and it makes sense that they want it back. However, from my point of view as a visitor to London, I’d much rather walk 2 minutes from the Arran House to see the Rosetta Stone than have to fly the whole way to Egypt.

From what I’ve seen of it, The Victoria and Albert Museum isn’t quite so overwhelmingly imperialistic, though that might be because I wasn’t able to visit the international sections of it (yet). From what I have seen, a lot of the materials was donated or otherwise given to the museum, as opposed to the British Museum’s acquisition by domination feel. All the same, the V&A made me feel like it was trying to show me how awesome England was in its heyday, and was probably first started to glorify the power of the Empire. Now, it serves as the world’s largest decorative arts and design museum, covering varieties of art like glass, ceramics, metalwork, stained glass, theatre and performance, along with sections on Victorian English home furnishings and more “traditional” pieces like paintings and sculpture from ancient through modern times. Even now, it is a very daunting place (I only got lost two or three times), but at the same time, it is a very fun place. Where else in the world can you see an Apple computer and a 1980’s Save the Miners mug on display in the same museum as priceless jewelry from centuries ago and costumes from the musical version of The Lion King?

Categories: 2010 MatthewM · Museums

Tagged: Imperialism

Yes- I guess we unanimously agree that the National Portrait Gallery was filled with portraits of the white and wealthy. There were no representations of middle or lower class, or any people of color, which didn’t come as a surprise to me. If you weren’t royalty or didn’t have a consistent money flow, you most definitely had no chance of getting your portrait done; hence no people of color. I was however pleasantly surprised with the amount of portraits of women- I expected it to be much less. There were a number of beautifully depicted portraits of women in intricately designed gowns that probably made every woman wonder what it would be like to have been in their shoes. As I began to take a closer look at each woman’s face, I noticed a similar characteristic; a majority of them were extremely pale and emotionless. After a while, I began to realize they all had to same face and the only things that differed were the color of the background, hairstyle, and attire.

As I was just about getting fed up with seeing identical miserable portraits, I came across a portrait of Mary Moser by George Romney in 1770

.

(Taken from the National Portrait Gallery)

Mary was an English painter and one of the most celebrated women artists. Very popular in the 18h century, Mary was known for her depictions of flowers and had been recognized as an artist since the young age of 14. I was thrilled to see a woman who was an individual and tapped into her own talent to make a living, instead of sitting upon hereditary wealth. Romney did an excellent job in captivating Mary doing what she loved while expressing the happy look upon her face. So in the end, I didn’t walk out of the National Portrait Gallery completely disappointed as I envisioned.

Categories: 2010 Melissa · Uncategorized

Tagged: 2010 Melissa, Mary Moser, National Portrait Gallery

I went to the British Library today to get a library card and begin research. In the two hours I spent there I acutely encountered an English phenomenon that Professor Qualls has described. I suppose I would call it ‘the run around.’ It is a fairly backwards system in which nothing can be accessed directly or simplistically acquired. At every turn this system required another step or was made more complicated or forbade me from receiving normal library benefits. The miserable experience began when I tried to get a library card. I had a passport sized photo and the letter from the University of East Anglia so one would think this process would be simple. And one would be wrong.

First, I had to fill out a list of the books that I would be getting out. Let’s, you and I, reader and myself, take a moment to consider this task. Here I am, setting foot in this library for the first time. I plan on searching through the databases and selection of books to find something worthwhile for research. However, before I have done so, I am obligated to say which books I will be using. While clearly I can just fudge a few names onto the page and say these are the ones I’ll be using, the idea behind the request seems to only serve as an impediment to a process that should be quite simple.

So I fudge the titles, finally get the card after a solid half hour of pure, cool, wasted life and head over to the Humanities section. From there, I’m redirected down to a bag section where I wait in a queue in order to put my backpack in a closet. Why this section was not outside the area I was not allowed into with it remains a mystery. Moving on, I was told that certain books were being kept in Yorkshire and for that reason are only available to be ordered for forty-hours later, which is perfectly understandable. However, when I ordered my books not marked as being kept in Yorkshire, I received a figurative swift kick in the pants. To receive any book from anywhere in the library takes seventy minutes. For effect, I’ll repeat that. Seventy minutes. Yes, that is for any book. Seventy minutes.

Why couldn’t I go up directly to someone working at the Library, ask them where the book was, and retrieve it in, say, 15 minutes? Perhaps because that would be too easy and too simple. Perhaps because the Brits are afraid of direct contact. Or perhaps it is because they take a sick pleasure in watching people go up and down escalators getting progressively more cranky and hungry! But I put that behind me, and said, well, I’ll just wait the seventy minutes and take my requested book out and look at it tonight after dinner, because I was preposterously famished at this point, as I hadn’t anticipated the hundred (70+30) minute process I would encounter before even looking at my first source. At this point, The British Library hit me one final time, delivering a knockout blow. I was informed that you cannot check books out. That’s not a typo nor an exaggeration, folks, you really can’t. I’m not just yankin’ the ol’ chain there. So, in a huff, I left, vowing never to return.

Until tomorrow when my books arrive.

Categories: 2010 Michael

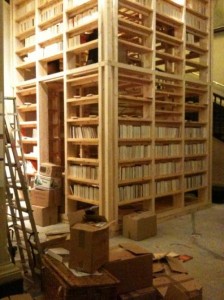

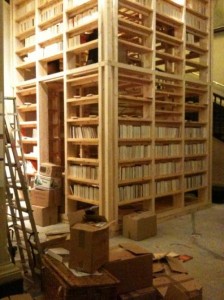

When going to the Victoria and Albert Museum the first rule is: do not get a map. It is completely useless. It will only make you more confused (if that is at all possible). The Victoria and Albert is like no other museum I’ve ever been to. Instead of the sparse but well cataloged rooms of the British Museum or the abstract instillation art of the Tate Modern, there is just “stuff.” It feels as if one has stumbled into a very eccentric, very wealthy old man’s closet. There is a vague sense of organization, but the curator has not stuck to a strict order. Instead one is assaulted with a variety of priceless artifacts. To top the disorganization of the rooms is the disorganization of the building itself. The rooms flow into one another like a maze. From the moment I walked in I should have known that it was going to be a completely new experience — immediately outside of the tube station there was an exhibit filled with treasures that would have been centerpiece at many smaller museums. I then continued into the fashion exhibit which was filled with a barrage priceless vintage clothing from across the world. From there we went through the sculpture hall to the one piece that I felt summed up the museum as a whole: a book tower. It was a multi-storied wooden structure just filled with a random assortment of books — everything from romance novels to Chaucer to Russian literature. This disorganization and jumble of priceless and random books should have been an indicator that my day was about to get a lot more impressive.

(courtesy of http://www.vam.ac.uk/things-to-do/blogs/11-architects-build-small-spaces)

(courtesy of http://www.vam.ac.uk/things-to-do/blogs/11-architects-build-small-spaces)

The madness of the Victoria and Albert reached its pinnacle in the Medieval and Renaissance section where upon a cursory browsing I stumbled upon a little journal tucked away behind a wall. This journal was not accompanied with any great display or paired with a painting or some other artifact — it stood on its own. This unassuming little book turned out to be a Da Vinci journal. If it had not been for the presence of a gold plaque indicating that it was something special I would not have even read the explanation. However, it was a room full or gold plaques and priceless artifacts and it was a completely fluke that I stopped and looked. From this point on, I just gave up. I was too incredulous to take the Victoria and Albert seriously. In a world where small local museums are starving for artifacts the Victoria and Albert have so many that they just cannot display them to their full potential. I personally wish that the Victoria and Albert would loan out items to eliminate the clutter and share their wealth. This would make the museum less overwhelming and it would allow more people to view more fascinating treasures.

Categories: 2010 Amy · Museums · Uncategorized