In the early 1920’s Russia was recovering from the revolution and the following civil war. A famine was underway and the country was in disarray after the chaos of the last few years. In response the Soviet Union started enacting new policies to get the economy and the industrial section back on track. First they established the First Labor Army. This organization used men from the military to do labor in order to further the industrial sphere of Russia. The labor included coal, lumber, and others. It was enacted not only to further the industrial area of Russia but also to keep people alive. Russia was in the midst of a famine because of the disorder in the country. The workers in the factories were losing ground and a major act was necessary to turn things around. Also enacted was the New Economic Policy. In 1921 the Soviet Union changed the ways peasants were taxed. Instead of the grain requisitions, excess food was to be given to the government. As it became more common, this tax, in the form of supplies, transitioned into a monetary exchange. This policy was unusual for the Soviet government as usually exchange happened through the government rather than this people centered form. Both of these policies were criticized for their similarities to pre-revolution ideas. Many peasants believed that the labor army and the new form of taxation were too similar to serfdom. But these new policies fulfilled their purpose: rebuilding Russia.

Tag Archives: Russia

Deities of Derivatives

In Zamyatin’s bizarre and ingeniously sobering novel of “We”, ((Zamyatin, Yevgeny. We. New York: Modern Library, 2006.)) rationality triumphs emotion as mathematics reigns as the supreme dogma of the individual’s life and mind. Of course, in this case, the term “individual” refers to the collective mass of workers known as ciphers who exist as mere figures in the long string of omnipotent code that is the dull and gray One State. Freedom is condemned as an uncouth crime while whimsical dreams and fits of inspiration are cruelly filed under the category of epileptic anomaly. The hero, and eventual martyr, of the story is D-503, a thirty-two-year-old cipher who is in charge of building the Integral, a marvelous product of modern science and technology purposefully constructed in order to integrate extraterrestrial societies into the blissful monotony of the One State. D-503 venerates mathematics and the exquisitely logical “Table” that dictates every hour of his daily life apart from his sexual, and even that is governed by the rules of “Paternal & Maternal Norms” and pink tickets. His life changes drastically as he is violently birthed into a world of vibrant color and independent thought propagated by a female cipher, I-330, who quite literally grasps him by his shaggy, primitive-like hands and pulls him out.

New, revolutionary ideologies spread within D-503 like a cancer, resulting in the proliferation of disinformation and disaggregation that are so dreadfully toxic to the prosperity of the One State. The cast-iron hands that of the Benefactor that seem to preside over all are defied, rejecting one of the core principles of the later Russian Revolution; the worship of industry and enthrallment of efficiency, as seen through the famed ideas of Taylor the economist that are so imbued within the novel. Zamyatin sees the dark side of the revolution, and generates an unsettling world that causes one to fear philosophies such as that of the poet Kirillov in his work The Iron Messiah. ((Kirillov, Iron Messiah)) The novel continuously examines the effects of antireligion, in which old, conservative traditions are ironically replaced with new progressive ideals embodied in the exaltation of mathematics and machinery. Through the terror of the guardians and vice-like grip of Communism, the people are forced to march along with eyes lowered and minds shut. Nonetheless, the subjugation by the One State of its people is not infinite; as per the existence of the irrational root of negative 1, there will always exist a number that rational governance is unable to enslave.

Emotion versus Reason

We by Yevgeny Zamyatin is a complex and revolutionary novel of Science fiction. D-503 is a mathematician living in the One State, journaling his daily life in order for future generations to learn about his society once the journal is put on the Integral (the spaceship D-503 is building). As a mathematician D-503 experiences the world in equations, from describing pleasing aesthetics to eventually emotions such as love with math (L=f(D): love is a function of death). ((Zamyatin, We 119)) Everything in the One State is measured and accounted for, using a Taylor system of time tables to block off the day. I-330 is the catalyst of all change in D-503’s life. Through the acquaintance of I-330, D-503 develops “an incurable… soul” and becomes aware of the confines of life within the One State. ((Zamyatin, We 79)) I-330 is a member of MEPHI (Mephisto), a rebellion group which stands for Anarchy, and who’s goal is to help the cave-man like creatures that live beyond the enclosing wall of the One State’s territory to break through and take down the current regime. ((Zamyatin, We 144)) Eventually D-503 is overcome with the events and turns himself in to the Bureau of Guardians, thusly turning over all of the rebels as well. The novel ends with a short entry from D-503 post-Opperation and devoid of human emotions. D-503 is only a shell of his former self as he watches without sympathy as I-330 is tortured for information, finally saying that “reason will win” and once again becoming a full supporter of the One State. ((Zamyatin, We 203))

We is a novel full of dichotomies, the most prevalent of which is reason versus emotion. The One State is obsessed with controlling it’s population, causing the people to become more machine than men. As D-503 states. “love and hunger are the masters of the world”; by regulating everything in life so closely even natural human emotions such as love become a designated hour of the day. ((Zamyatin, We 20)) Emotions have the power to effect change, which is one reason why I-330 is able to create a following of revolutionaries. One cause of the creation of the Operation is the rebellion, and the need to eliminate ‘dangerous’ qualities of people for the safety if the One State. The great struggle of the novel is increasing regulation over the daily life of citizens of the One State, with the inhabitants being as oblivious as possible, because once time doesn’t belong to themselves the only option left is to devote their entire lives to the good of the state.

Progress Rooted in Past Art

“Peasants Dancing” Goncharova (1911) http://nga.gov.au/international/catalogue/Images/LRG/156812.jpg

The end of the nineteenth century ushered in new movements in Russian poetry, art, dance, and music, which continued to grow throughout the early twentieth century. The movement sought to unify all forms of art and promoted collaboration amongst artists. Companies such as the Ballets Russes merged artists of all disciplines, from painters to musicians, in their shows. As this new wave of Russian art progressed, the past was often rejected in favor of a belief in progress through the unification of the Russian people. Though the past was often rejected, once the Russian Socialist Revolution occurred, Bolshevik politicians such as Lenin and Lunacharskii failed to recognize the value of the past in the proletariat movement.

In The Proletariat and Art, Alexander Bogdanov stated the important role of art in the organization and unification of a strong proletariat. ((http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1917-2/culture-and-revolution/culture-and-revolution-texts/the-proletarian-and-art/)) However, he argued that the proletariat should critique past art rather than reject it in its entirety. Instead, traditional Russian art provided an opportunity for the working class to find new interpretations of the artworks in order to learn from it through a proletarian lens. According to Bogdanov, if the proletariat could find new meaning in these pieces of art to advance their own agenda of unity and collectivization, then past artwork would work as a tool to strengthen the proletariat. Further, critiquing traditional artwork would allow the proletariat to understand the past and ensure that it would not repeat itself.

In contrast to Bogdanov’s work, Lenin and Lunacharskii completely rejected artworks and effigies of the Tsarist regime in The Monuments Policy. ((http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1917-2/culture-and-revolution/culture-and-revolution-texts/decree-on-the-removal-of-monuments-erected-in-honor-of-the-tsars-and-their-officials-and-the-setting-up-of-designs-for-monuments-of-the-russian-socialist-revolution/)) The document maintains that the removal of monuments built under the Tsarist regime was necessary because they were of no artistic value. The statement that these monuments had no artistic value ignored Boganov’s idea that they had a potential purpose in the overall progress of the proletariat.

Elements of the past were often present in Russian art, such is in Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” and in Goncharova’s Primitivist paintings. ((http://artinrussia.org/natalia-goncharova/ ; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jF1OQkHybEQ)) These artists believed in the progress of a unified Russian society, but they used symbols of the past in their works to demonstrate its role in inciting this progress. Though the music of “Rite of Spring” employs modern techniques, it is juxtaposed with traditional tribal dancing and costumes in the ballet. Further, Goncharova’s Primitivism was a modern art technique, but it focused on artistic styles and methods of the past. Lenin and the Bolsheviks failed to recognize the importance of the past in art and in a successful proletariat society as a whole.

Revolutionary Poetry

With the rise of literacy in Russia, literature became a more effective way to spread ideas throughout the people. Poetry stands out from the other forms here due to it’s rhythm. It is easier to remember stanzas of poetry than prose. This makes poetry a fantastic way to spread revolutionary ideas as well as the cost of the revolution.

Maksimilian Voloshin writes about how often progress is reached by some sort of sacrifice. In his poem, “Holy Russia” he describes the destruction that has come as a result of the revolution. “You yielded to passion’s beckoning call, And gave yourself to bandit and to thief, You burned your barns and fired your mansions, Pillaged your ancient house and home, And went your ways reviled and wretched, The handmaid of the humblest slave.” (( Voloshin, Holy Russia, http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1917-2/culture-and-revolution/culture-and-revolution-texts/holy-russia/ )) Voloshin tells of a Russia that has been torn apart by revolution, but that has the ability to make tremendous progress, something that would be positive to hear after years of brutal civil war.

Meanwhile, poets such as Kirillov and Gastev wrote on the glorious aspect of the revolution that came out of industrialization. In the poems, “Iron Messiah” and “We Grow Out of Iron” a new, magnificent future is made possible by the revolution, which was made possible by the machine. The machine allowed the proletariat to rise, and it will continue to allow for equality. Kirillov writes, “All of steel, unyielding and impetuous; He scatters sparks of rebellious thought,” this emphasizes the importance of technology in the minds of the revolutionaries. ((Kirillov, Iron Messiah, http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1917-2/culture-and-revolution/culture-and-revolution-texts/the-iron-messiah/ )) The machine represents power, equality, and progress, all which were goals of the revolution. This can be seen in the writing of Gastev, “I shall not tell a story or make a speech, I will only shout my iron word: “Victory shall be ours!”” ((Gastev, We Grow Out of Iron)) The use poetry to expand this message to the people emphasizes the importance of continuing to produce for the state using the technology that set them free.

These poets help to inspire the people that this suffering during the revolution is for a greater cause, but also that the very machines that made their lives harsh were the ones that liberated them. I think it is very interesting how the description and imagery of heavy machinery would fit right into a Western capitalist propaganda ad, but it can also be used to inspire the workers.

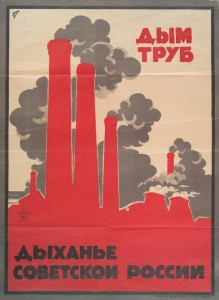

“The smoke of chimneys is the breath of Soviet Russia” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Soviet_Union_(1927–53)

Propaganda by Rail

In the early twentieth century the most effective means of traveling the country was by rail systems. Because of the rails already set in place throughout Russia the logical way to reach the people was to use the trains. The first of the trains to reach the isolated peasantry was know as “Lenin’s train.”[2] This train was made up of 15 cars and “decorated with paintings in bright colors, with forceful and unmistakably revolutionary inscriptions.”[3] It is important to note, that the officials onboard the train were members of branches of the “people’s Commissariat.”[4] These men would distribute masses of pamphlets and readings free of charge to the people, as well as answer questions and advise on issues concerning the population. This was a powerful tool for the Soviet government to use, as the population will feel heard, and important to the government. This in turn will promote less resistance to newer ideas and obedience. The feeling of solidarity between the government and the workers was to be fostered in this way.

The success of such trains in spreading soviet propaganda prompted the creation of three further trains, with different routs that would bring the word of the “Revolution” to the “most hidden nooks of Soviet Russia.”[5] These propaganda trains would be responsible for returning the wishes of the people to the government and create an environment where capitalist imperialism would be unable to return to the minds of the population.

[1] Hoffmann, “European Modernity and Soviet Socialism” in Hoffmann and Kotsonis, eds., Russian Modernity: Politics, Knowledge, Practices (NY: St. Martin’s, 2000), 245-260.

[2] Iakov Okunev, A New Way for Culture Propaganda. 1919

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Agit-train October Revolution / Vertov-Collection, Austrian Film Museum

Russia and Ukrainian (In)Dependence

It is clear that the revolutions that occurred in Russia in 1917 did not only affect Russia, but also its neighboring nation, Ukraine. The Revolutions may have even inspired the people to host their own rebellions. On June 10, 1917 the First Declaration of the Rada took place. In this Declaration, the congress explained their responsibilities to protect the rights and freedoms of the Ukrainian land and its wish to have a free Ukraine without separating from all of Russia. However, the declaration then explains how the Russian Provisional Government ignored demands by Rada delegates and did not wish to work with the Rada to build a new regime. With that, the Rada declared that they would work to reach autonomy in the Ukraine. On December 12, 1917, just about six months after the First Declaration of the Rada, was the Self-determination of the Ukraine. This all-Ukraine Congress of Soviets, like in the Declaration of the Rada, declared goals for bettering Ukrainian life. However, in the Self-determination, the congress rejected the Rada and claimed them to have a counter- revolutionary nature. The Self- determination focused on workers and peasants, the lower classes, and their rights and freedoms. Also, this congress chose to recognize Ukraine as a federal part of the Russian Republic and was far more focused on protecting worker’s rights than on Ukrainian independence.

Both congresses expressed a want for freedom from Russia but also seemed to have some anxiety about complete independence. The First Declaration only declared a want for autonomy after explaining how its original request to work with the Russian Provisional Government was rejected. The Self-determination of the Ukraine did not outwardly state a want for independence from Russia but did express Ukrainian pride and independence by stating the congress’s job to fight for the self-determination of the Ukraine in the interests of the workers and peasants. However, the Self-determination does outwardly recognize the Ukrainian Republic as a federal part of the Russian Republic and did not express a desire to change that. The declarations differed in that the Self-determination of the Ukraine was concerned mostly with workers and peasants and their rights and overall quality of life whereas the Central Rada expressed more general goals of independence from Russia. It seemed even that if the Central Rada was more concerned with the lives of workers and peasants and less so with independence form Russia, that the Congress of Soviets would not have rejected them in their Self-determination of the Ukraine.

Both congresses were simply looking for a better quality of life; the Central Rada believed that this could only happen after independence from Russia and the All-Ukraine Congress of Soviets seemed to believe unity with Russia would bring the best benefits, at least for the lower classes. Possibly the revolutions in Russia at the time confused the Ukrainians on where Ukraine stood in relation to Russia and what would be more beneficial to the people of the country, autonomy or unity.

Promises and Principles: The New Provisional Government

With the famed abdication of Tsar Nicholas II on the fateful day of March 15, 1917, Russia experienced a drastic paradigm shift in the manner of political atmosphere and public perception of the socioeconomic status quo that had previously prevailed for centuries. The Tsar relinquishes his omnipotence as the autocratic ruler of the state with a charismatic speech venerating “the destinies of Russia, the honour of her heroic Army, the happiness of the people, and the whole future of our beloved country” ((The Times, Abdication of Nikolai II, March 15, 1917)). His declaration is a notion of nationalism; an appeal to the people to lead the country onto a noble path of wealth and power so that it may become transfigured into a prosperous utopia freed from the “obstinate war” ((The Times, Abdication of Nikolai II, March 15, 1917)) that had so dreadfully plagued the nation. The culmination of the speech is veiled with a sense of desperation and subservience to fate, as it ends with a single note of hope encompassed within the phrase: “May God help Russia” ((The Times, Abdication of Nikolai II, March 15, 1917)).

The cataclysmic prostration of the autocracy before its own people is further exemplified by the refusal of the Tsar’s heir, Grand Duke Mikhail, to take over the throne. He states that he is “firmly resolved to accept the Supreme Power only if this should be the desire of our great people” ((The Times, Abdication of Nikolai II, March 15, 1917)) and acknowledges the pressing need for implementing political change and widespread popular suffrage. This thus allowed for the bold entry of the First Provisional Government, also known as the Temporary Committee of the State Duma. The first provisional government set the stage for what would be known in the future as democratization and an attempt to establish popular sovereignty. The doctrines that it placed forth and advocated were interwoven with liberalism and bordered upon the early principles of communism, and included the desire to “abolish all restrictions based on class, religion, and nationality” as well as “an immediate and complete amnesty in all cases of a political and religious nature” ((Izvestiia, The First Provisional Government, 1917)). This legislation envisioned a blissful yet unrealistic system that consisted of sharp implementation of the fundamental rights to freedom of speech, press, and assembly, while simultaneously embodying peace. The framework of ideologies that the Duma mapped out was much to feeble to counter the strain of the political perturbation the nation underwent in such a short period of time. The Duma eventually failed in its quest to craft an immense revolution and to enforce each and every one of its progressive reforms, yet also allowed for an eruption of a new form of government that would be capable of embodying the true radical spirit of change: the Bolsheviks of 1917.

The Demise of the Romanov Dynasty

After over three hundred years of Russian rule by the Romanov Dynasty, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated his throne in March of 1917. The Russian leader was facing popular unrest over an enormous wealth gap and then chose to thrust his nation into an expensive and bloody war against Germany. Nicholas’ rule had experienced an uprising in 1905 which persuaded him to call a supposedly representative body known as a Duma, but the Tsar’s refusal to accept any of the body’s proposals only fueled discontent among the people. By 1917, Nicholas “recognized that it [was] for the good of the country that [he] should abdicate the Crown of the Russian State and lay down the Supreme Power.” ((Abdication of Nikolai II)) The Tsar blamed the domestic strife for further stunting the war efforts, but he claimed that “the moment [was] near when our valiant Army, in concert with out glorious Allies, will finally overthrow the enemy.” ((Abdication of Nikolai II)) Despite his apparent optimism, he decided to leave the Crown to his brother Mikhail Alexandrovich, who was equally hesitant about shouldering the burden of the Russian State. Mikhail dubbed the power bestowed on him as a “heavy task” ((Declaration from the Throne by Grand Duke Mikhail)) and left control to a provisional government. He hoped to avoid further public outcry by promising the populace a role in deciding what type of government would next rule over Russia.

The First Provisional Government proposed a liberal set of guidelines in the wake of the Tsar’s downfall. The people the cabinet presided over were meant to have freedom of speech, relative freedom of religion, universal suffrage, the power to elect those who will hold office, and universal pardons for anyone accused of political crimes. ((The First Provisional Government)) It would not hold true to its promise of a direct vote for the constitution and form of government that would lead Russia. Multiple provisional governments would be established before the so called Bolshevik Revolution just a few months later in November of 1917. The Revolution was technically a bloodless coup, orchestrated by Vladimir Lenin who would hold power until his death.

Abdication and Creation of a New Russia

After almost two hundred years of expanding a nation that would be respected as an equal to the Western European states, the Russian Empire fell. The 1917 Revolution in March called for the abdication of the Tsar, Nicholas II, as well as the need for a government of the people to take its place. When Nicholas abdicated though, he appointed his brother, the Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich, as his heir; he was the next to rule what was left of this grand Empire. But the citizens weren’t calling for a different monarch, but a new form of government altogether. Mikhail seemed to sense this, since in his response to his new title, he declared that he would rule until the “will of the nation regarding the form of government to be adopted.” (( http://community.dur.ac.uk/a.k.harrington/abdicatn.html )) He wanted for the people to choose what they wanted out of a government and was willing to take charge just until that moment.

The First Provisional Government based itself on the principles that one sees in a democratic government’s ideals, such as freedom of free speech, press and assembly, anti-discrimination, universal suffrage, and elections for positions of governments. (( http://community.dur.ac.uk/a.k.harrington/provgov1.html )) But there are some surprising conditions that appear too in their Statute. They promise immediate amnesty to acts such as terrorism and revolts and protection for those in the military that took part in the revolution. While these may seem surprising at first, they make sense in terms of the goals of the new provisional government. These ten men were presumably at the heart of the revolution, or at least in favor of what the revolutionaries were doing, or else they would not have gotten such high positions in the cabinet, so it makes sense that they would pardon men who were arrested by the old government if they were on the same side. Both the fall of the centuries-long monarchy and the beginning of a new government were new experiences for the Russian people that changed their lives for better or worse.