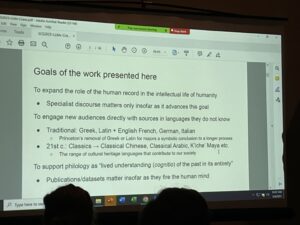

Fresh off the stimulating Digital Classics Association panel at the 2025 SCS on uses of AI in classical scholarship, I decided to give ChatGPT 4 and Claude 3.5 Sonnet a crack at one of the central tasks of DCC: creating accurate vocabulary lists.

περὶ ἀρετῆς, ὦ Κλέα, γυναικῶν οὐ τὴν αὐτὴν τῷ Θουκυδίδῃ γνώμην ἔχομεν. ὁ μὲν γάρ, ἧς ἂν ἐλάχιστος ᾖ παρὰ τοῖς ἐκτὸς ψόγου πέρι ἢ ἐπαίνου λόγος, ἀρίστην ἀποφαίνεται, καθάπερ τὸ σῶμα καὶ τοὔνομα τῆς ἀγαθῆς γυναικὸς οἰόμενος δεῖν κατάκλειστον εἶναι καὶ ἀνέξοδον. ἡμῖν δὲ κομψότερος μὲν ὁ Γοργίας φαίνεται, κελεύων μὴ τὸ εἶδος ἀλλὰ τὴν δόξαν εἶναι πολλοῖς γνώριμον τῆς γυναικός: ἄριστα δ᾽ ὁ Ῥωμαίων δοκεῖ νόμος ἔχειν, ὥσπερ ἀνδράσι καὶ γυναιξὶ δημοσίᾳ μετὰ τὴν τελευτὴν τοὺς προσήκοντας ἀποδιδοὺς ἐπαίνους. διὸ καὶ Λεοντίδος τῆς ἀρίστης ἀποθανούσης, εὐθύς τε μετὰ σοῦ τότε πολὺν λόγον εἴχομεν οὐκ ἀμοιροῦντα παραμυθίας φιλοσόφου, καὶ νῦν, ὡς ἐβουλήθης, τὰ ὑπόλοιπα τῶν λεγομένων εἰς ‘τὸ μίαν εἶναι καὶ τὴν αὐτὴν ἀνδρὸς καὶ γυναικὸς ἀρετὴν προσανέγραψά σοι, τὸ ἱστορικὸν ἀποδεικτικὸν ἔχοντα καὶ πρὸς ἡδονὴν μὲν ἀκοῆς οὐ συντεταγμένα εἰ δὲ τῷ πείθοντι καὶ τὸ τέρπον ἔνεστι φύσει τοῦ παραδείγματος, οὐ φεύγει χάριν ἀποδείξεως συνεργὸν ὁ λόγος οὐδ᾽ αἰσχύνεται

ταῖς Μούσαις

τὰς Χάριτας συγκαταμιγνὺς

καλλίσταν συζυγίαν,

ὡς Εὐριπίδης φησίν, ἐκ τοῦ φιλοκάλου μάλιστα τῆς ψυχῆς ἀναδούμενος τὴν πίστιν.

Regarding the virtues of women, Clea, I do not hold the same opinion as Thucydides. For he declares that the best woman is she about whom there is the least talk among persons outside regarding either censure or commendation, feeling that the name of the good woman, like her person, ought to be shut up indoors and never go out. But to my mind Gorgias appears to display better taste in advising that not the form but the fame of a woman should be known to many. Best of all seems the Roman custom, which publicly renders to women, as to men, a fitting commemoration after the end of their life. So when Leontis, that most excellent woman, died, I forthwith had then a long conversation with you, which was not without some share of consolation drawn from philosophy, and now, as you desired, I have also written out for you the remainder of what I would have said on the topic that man’s virtues and woman’s virtues are one and the same. This includes a good deal of historical exposition, and it is not composed to give pleasure in its perusal. Yet, if in a convincing argument delectation is to be found also by reason of the very nature of the illustration, then the discussion is not devoid of an agreeableness which helps in the exposition, nor does it hesitate

To join

The Graces with the Muses, A consorting most fair,

as Euripides says, and to pin its faith mostly to the love of beauty inherent to the soul.

I gave both AIs a lengthy prompt, similar to what I would say to a human if I were tasking her with creating a vocabulary list:

I am going to attach a .txt file with some Ancient Greek. I want you to create a vocabulary list for the text. Each entry in the list should contain the standard dictionary form of the token, followed by an English definition appropriate to the context. For example, given the token γυναικῶν, the entry in the list should read “γυνή γυναικός, ἡ: woman.” γυνή γυναικός, ἡ is the dictionary form. This token is a noun, so it includes the nominative singular, γυνή, followed by the genitive singular, γυναικός, followed by a comma, then the feminine form of the definite article (ἡ), indicating it is a feminine noun. After that comes a colon, which separates the dictionary form from the English definition. I used “woman” in this example rather than “wife,” which is another possible definition. In the context from which I took the example, the author is discussing women in general, not just wives. Here is a second example, this time for a verb. The token is ἔχομεν. The dictionary form is “ἔχω, ἕξω or σχήσω, 2 aor. ἔσχον, ἔσχηκα, impf. εἶχον” . I derived this dictionary form from the Dickinson College Commentaries site https://dcc.dickinson.edu/greek-core-list . Use that if you can, but that doesn’t have all words. For words not in that source, use the fuller list in the Grieks Nederlands dictionary available on the site Logeion https://logeion.uchicago.edu/ . If the dictionary form there is very long, try to simplify it based on the format of the Dickinson College Commentaries list and the following list of further examples, which includes some adjectives, adverbs, and verbs.

ὑπόληψις -εως, ἡ: opinion, assumption

ὁρμή -ῆς, ἡ: impulse

ὄρεξις -εως, ἡ: desire

ἔκκλισις -εως, ἡ: aversion, avoidance

κτῆσις -εως, ἡ: possession, property, property

δόξα -ης, ἡ: opinion; reputation

1.2

ἀκώλυτος -ον: unhindered

ἀπαραπόδιστος -ον: unimpeded, unobstructed

ἀσθενής -ές: weak, powerless

δοῦλος -η -ον: slavish, servile

κωλυτός -ή -όν: hindered

ἀλλότριος -α -ον: not one’s own, under the control of others

1.3

ἐμποδίζω -ποδιῶ -επόδισε: to hinder, frustrate

πενθέω -ήσω ἐπένθησα: to mourn, to suffer pain

ταράσσω ταράξω ἐτάραξα: to trouble, disturb

μέμφομαι μέμψομαι ἐμέμφθην: to blame

ἀναγκάζω -άσω: to force, constrain

οὐδέποτε: not ever, never

ἐγκαλέω ἐγκαλῶ ἐνεκάλεσα: to rebuke, reproach + dat.

ἄκων -ουσα -ον: involuntarily, against one’s will

βλάπτω βλάψω ἔβλαψα: to harm, hinder, disable

βλαβερός -ά -όν: harmful

1.4

τηλικοῦτος -αύτη -οῦτον: such great

ἐφίημι ἐφήσω ἐφῆκα: to aim at, to long for, desire + gen.

μετρίως (adv.): moderately

ἅπτω ἅψω ἥψα: to grasp, obtain, engage in, undertake (+ gen)

παντελῶς (adv.): absolutely, completely

ὑπερτίθημι ὑπερθήσω ὑπερέθηκα: to defer, put off

πλουτέω -ήσω ἐπλούτησα: to be rich or wealthy

ἀποτυγχάνω ἀποτεύξομαι ἀπέτυχον: to fail in attaining, miss

ἐλευθερία -ας, ἡ: freedom

εὐδαιμονία -ας, ἡ: prosperity; true, full happiness

περιγίγνομαι περιγενήσομαι περεγενόμην: to be a result or consequence, to arise

You will notice that adverbs sometimes have “(adv.)” at the end of the dictionary form. That is desirable. Note also that when more than one English definition is given, sometimes those English definitions are separated by commas, and sometimes by semi-colons. The commas separate English definitions that are near-synonyms. The near synonyms are grouped together and separated from substantially different possible English definitions with a semi-colon. Notice also that there are milestones separating groups of entries that derive from a single paragraph or sentence, such as “1.1,” “1.2.” If the text I input seems to have section headers, either numerical like that, or a title, please include those on a separate line above the list of words for that section. Section headers often include English words.

That was the prompt. Claude made a nice summary of my prompt:

I understand you want me to create a vocabulary list from Ancient Greek text, following specific formatting rules. Each entry should have:

1. Dictionary form (using Dickinson College Commentaries when possible, otherwise simplified entries from Logeion)

2. English definition(s) appropriate to context

3. Special formatting for different parts of speech (e.g., adding “(adv.)” for adverbs)

4. Grouping similar English definitions with commas, different meanings with semicolons

5. Including section headers when present

6. For nouns: nominative + genitive + article

7. For adjectives: all gender endings

8. For verbs: principal parts in simplified format

I see you’ve provided helpful examples to guide the formatting. However, I don’t see the actual Greek text file you mentioned wanting to attach. Could you please share the text you’d like me to analyze? Once you do, I’ll create a vocabulary list following these specifications.

I will paste the raw results below. I also have the results in a Word file, edited with track changes to show all the improvements I would make. If anybody wants that I can supply it. Here is my summary analysis.

- Both AIs did a superb job of crafting dictionary forms to my specifications.

- There were occasional errors of lemmatization, e.g. ἐπαινέω for ἔπαινος, σύζυγος for συζυγία, φιλοκαλέω for φιλόκαλος, ἄμοιρος for ἀμοιρέω. Claude was somewhat better at lemmatization than GPT, but both were very good. GPT astutely picked up an instance of ὁ μὲν … ὁ δέ: “on the one hand … on the other hand (used to contrast ideas).”

- Both helpfully omitted very common words, though I had given no instructions in that regard.

- Both omitted a number of uncommon words, 9 in the case if GPT, 15 in the case of Claude. Claude missed all the proper names.

- The definitions were generally very good. Rare meanings like παράδειγμα = “illustration” and ἀπόδειξις = “exposition” were missed by both AIs

- GPT tried to give a case-specific definition for μετά twice, and was wrong both times. On μετὰ τὴν τελευτὴν it offered μετά + gen.: “with, among”; on μετὰ σοῦ it offered μετά + acc.: “after.”

Very impressive, I would say, despite the errors. Just in terms of the formatting of dictionary lemmas, this will be a huge time saver. I don’t think we will abandon our usual workflow with the Bridge, but this is very much a viable option going forward.

The main thing I learned at the DCA panel is that you can put in huge prompts with elaborate instructions, no problem. Boy, do I feel slow now when I edit vocab lists, like a snail trying to keep up with a Lamborghini.

Ok, here are the raw results from GPT:

ἀρετή -ῆς, ἡ: virtue, excellence

γυνή γυναικός, ἡ: woman

Θουκυδίδης -ου, ὁ: Thucydides (name)

γνώμη -ης, ἡ: opinion, judgment, intelligence

ἔχω, ἕξω or σχήσω, 2 aor. ἔσχον, ἔσχηκα, impf. εἶχον: to have, hold, possess; to be able to

ὁ μὲν … ὁ δέ: on the one hand … on the other hand (used to contrast ideas)

ὀλίγος -η -ον: small, little, few

ψόγος -ου, ὁ: blame, criticism

ἔπαινος -ου, ὁ: praise, commendation

καθάπερ: just as, as if

σῶμα σώματος, τό: body

ὄνομα ὀνόματος, τό: name

ἀγαθός -ή -όν: good, noble, brave

οἴομαι, οἰήσομαι, ᾠήθην: to think, suppose, imagine

δεῖ: it is necessary, must

κατάκλειστος -ον: closed, shut in

ἀνέξοδος -ον: inaccessible, closed off

κομψός -ή -όν: refined, elegant, clever

Γοργίας -ου, ὁ: Gorgias (name)

κελεύω, κελεύσω, ἐκέλευσα: to order, command

εἶδος -ους, τό: form, shape, appearance

δόξα -ης, ἡ: opinion, glory, reputation

δημοσίᾳ (adv.): publicly, in public

μετά + gen.: with, among

τελευτή -ῆς, ἡ: end, death

ἀποδίδωμι, ἀποδώσω, ἀπέδωκα: to give back, return, pay

ἐπαινέω, ἐπαινέσω, ἐπῄνεσα: to praise, commend

Λεοντίς -ίδος, ἡ: Leontis (name)

ἀποθνῄσκω, ἀποθανοῦμαι, ἀπέθανον: to die

εὐθύς: immediately, at once

μετά + acc.: after

πολύς, πολλή, πολύ: much, many

λόγος -ου, ὁ: word, speech, discourse

παραμυθία -ας, ἡ: consolation, comfort

φιλόσοφος -ου, ὁ/ἡ: philosopher

βουλεύω, βουλεύσω, ἐβούλευσα: to deliberate, plan

ὑπόλοιπος -ον: remaining, left over

λέγω, λέξω or ἐρῶ, εἶπον: to say, speak, tell

μία -ας, ἡ: one, single

ἀνήρ ἀνδρός, ὁ: man, husband

καταγράφω, καταγράψω, κατέγραψα: to record, write down

ἱστορικός -ή -όν: historical

ἀποδεικτικός -ή -όν: demonstrative, explanatory

ἡδονή -ῆς, ἡ: pleasure, delight

ἀκοή -ῆς, ἡ: hearing, sense of hearing

συντάσσω, συντάξω, συνέταξα: to arrange, compose

φύσις -εως, ἡ: nature, character

παράδειγμα -ατος, τό: example, pattern

λόγος -ου, ὁ: reason, word, account

χαρίς -ίτος, ἡ: grace, favor, kindness

Μοῦσα -ης, ἡ: Muse (goddess of art and inspiration)

Χάρις -ιτος, ἡ: Grace (one of the Graces)

καλλίστος -η -ον: most beautiful

σύζυγος -ον: yoked together, paired

φιλοκαλέω: to love beauty, to be elegant

ἀναδέω, ἀναδήσω, ἀνέδησα: to bind up, to crown

And here are the raw results from Claude:

Let me create a vocabulary list for this text from Plutarch’s “On the Virtues of Women.”

Title: On the Virtues of Women (Introduction)

ἀρετή -ῆς, ἡ: excellence, virtue

γυνή γυναικός, ἡ: woman

γνώμη -ης, ἡ: opinion, judgment

ἔχω, ἕξω or σχήσω, 2 aor. ἔσχον: to have, hold

ἐλάχιστος -η -ον: least, smallest

ψόγος -ου, ὁ: blame, criticism

ἔπαινος -ου, ὁ: praise

λόγος -ου, ὁ: word, speech; account

ἄριστος -η -ον: best, excellent

ἀποφαίνω -φανῶ -έφηνα: to show, declare, present

σῶμα -ατος, τό: body

ὄνομα -ατος, τό: name

ἀγαθός -ή -όν: good, noble

κατάκλειστος -ον: shut up, confined

ἀνέξοδος -ον: not going out, staying at home

κομψός -ή -όν: refined, clever

φαίνω φανῶ ἔφηνα: to show, appear

κελεύω -σω ἐκέλευσα: to order, command

εἶδος -εος, τό: form, appearance

δόξα -ης, ἡ: reputation; opinion

γνώριμος -ον: well-known, familiar

Ῥωμαῖος -α -ον: Roman

νόμος -ου, ὁ: law, custom

δημόσιος -α -ον: public

τελευτή -ῆς, ἡ: end, death

προσήκω -ξω -ῆξα: to be fitting, proper

ἀποδίδωμι -δώσω -έδωκα: to give back, render

ἄμοιρος -ον: without share in (+ gen.)

παραμυθία -ας, ἡ: consolation, comfort

φιλόσοφος -ον: philosophical

ὑπόλοιπος -ον: remaining, rest

ἀποδεικτικός -ή -όν: demonstrative, proving

ἡδονή -ῆς, ἡ: pleasure

ἀκοή -ῆς, ἡ: hearing

συντάσσω -τάξω -έταξα: to arrange, compose

πείθω πείσω ἔπεισα: to persuade

τέρπω τέρψω ἔτερψα: to delight, please

παράδειγμα -ατος, τό: example, model

φεύγω φεύξομαι ἔφυγον: to flee, avoid

χάρις -ιτος, ἡ: grace, charm; gratitude

συνεργός -όν: helping, cooperating

αἰσχύνω -νῶ ᾔσχυνα: to shame

Μοῦσα -ης, ἡ: Muse

Χάρις -ιτος, ἡ: Grace (one of the Graces)

συγκαταμίγνυμι -μίξω -έμιξα: to mix together, blend

καλός -ή -όν: beautiful, noble

συζυγία -ας, ἡ: union, pairing

φιλόκαλος -ον: loving beauty

ψυχή -ῆς, ἡ: soul

ἀναδέω -δήσω -έδησα: to bind up, crown

πίστις -εως, ἡ: trust, faith; proof