My fourth semester Latin students have just started reading Catullus, and I wanted a sight-reading activity that would reinforce the vocabulary from poems 12 (Marrucine Asini) and 13 (Cenabis bene). I asked ChatGPT to create a brief murder mystery in Latin involving the characters from the poems. Here is the yarn it spun. Prompt and Latin critique to follow . . .

Quis Marrucinum Asinium Necavit?

Marrucinus Asinius, notus linteorum fur, subito mortuus repertus est in villa Catulli. Corpus eius iacebat in tricliniis, inter vinum et reliquias cenae. Fabullus et Veranius, amici Catulli, stupefacti spectabant. Candida puella, quae nuper ad convivium venerat, fletu oculos suos tegebat. Catullus ipse, pallidus et tacitus, stabat prope corpus.

Fabullus dixit: “O di immortales! Quis hoc fecit? Marrucinus mihi linteum subripuit, sed num homicidium meruit?”

Veranius respondit: “Estne hoc opus irati Catulli? Tu saepe minatus es, Catulle, hendecasyllabos trecentos componere contra eum. Fortasse ira tua excessit in caedem.”

Catullus oculos sublatis vocavit: “Non ego! Quamvis illum furti accusaverim, nunquam tamen violentiâ usus sum.”

Tum Fabullus: “Sed quid de candida puella?”

Puella, lacrimis plena, dixit: “Marrucinus mihi insultavit in convivio! Sed num credetis me, fragilem feminam, eum necavisse? Non ego id feci!”

Omnes oculos in Fabullum verterunt. “Fabulle, quid dicis?” inquit Veranius. “Tu saepe Marrucinum avaritiae accusasti.”

Fabullus caput movere coepit: “Certe fur erat! Sed nec ego necavi! Certe linteum meum mihi carum erat, sed hoc non est causa caedis.”

Tum Catullus ad corpus accessit et rem miram animadvertit. “Ecce! Linteum Saetabum prope corpus iacet. Hoc linteum mihi a vobis donatum est, Fabulle et Verani! Num hoc est signum?”

Puella subridens respondit: “Signum, fortasse. Sed cur linteum afferre me putatis? Potius, spectate versum in pariete scriptum: ‘Fur et iniustus iacet. Hendecasyllabi ultorem iustitiam tulerunt.’”

Omnes stupuerunt. Veranius tremens dixit: “Hendecasyllabi? Num versus tuae irae, Catulle, animati facti sunt?”

Catullus suspiravit: “Fortasse versus mei plus potentiae habent quam ego imaginatus sum.”

Fabullus: “Itaque, non puella, non ego, non tu, sed hendecasyllabi ipse Marrucinum necaverunt?”

Puella ridens: “Quis scit? Forsitan poesis ipsa vindicem aequitatemque tulerit.”

Omnes tacuerunt, linteum et corpus spectantes. Vino mox impleverunt pocula et memoriam Marrucini – furis invisi sed hominis tamen – saltem modico risu honoraverunt.

The prompt was as follows. I was careful to specify my role, what I was trying to do, what I wanted the AI to do, and the format in which I wanted the results.

I am a Latin teacher. I am trying to create an easy Latin story for my students, who are at the intermediate level. I want the story to be a murder mystery, entitled, Quis Marrucinum Asinium necavit, or “Who Killed Marrucinus Asinius?” It should be in Latin, and the characters should include the people mentioned in Catullus’ poems 12 and 13. I will put those poems in the prompt. One of the characters, the victim, is Marrucinus Asinius, a napkin thief. I want the story to be a murder mystery in which Marrucinus shows up dead and it is unclear who has killed him. It could be the beautiful girl (candida puella) mentioned in poem 13, or it could be Catullus’ friends, Varnius or Fabullus, or it could be Catullus himself, or it could be the hendecasyllables, or lines of invective poetry mentioned in poem 12. I would like to use as much of the vocabulary that appears in poems 12 and 13 as possible, but it is also fine to use other common Latin words. The story should be about 300-500 words long.

Here is poem 12:

Marrucine Asini, manu sinistra

non belle uteris in ioco atque vino:

tollis lintea neglegentiorum.

hoc salsum esse putas? fugit te, inepte:

quamvis sordida res et invenustast.

non credis mihi? crede Pollioni

fratri, qui tua furta vel talento

mutari velit: est enim leporum

differtus puer ac facetiarum.

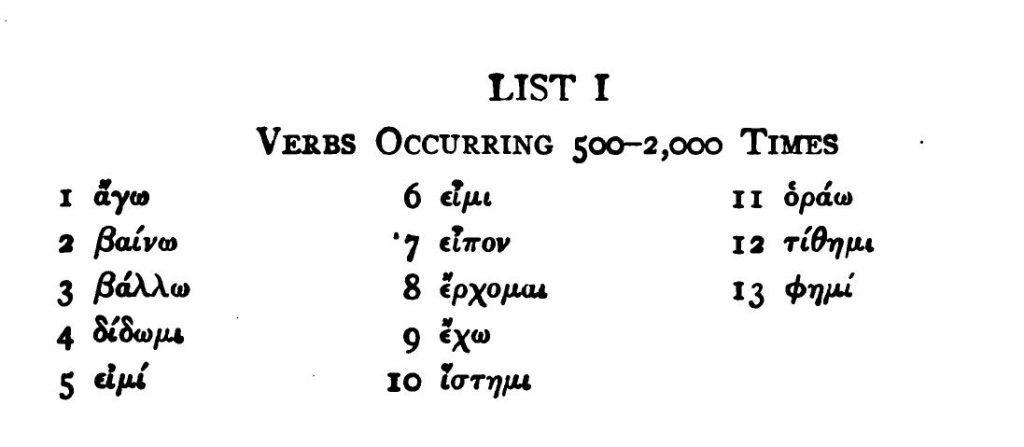

quare aut hendecasyllabos trecentos

exspecta, aut mihi linteum remitte;

quod me non movet aestimatione,

verumst mnemosynum mei sodalis.

nam sudaria Saetaba ex Hiberis

miserunt mihi muneri Fabullus

et Veranius: haec amem necessest

ut Veraniolum meum et Fabullum.

Here is poem 13:

Cenabis bene, mi Fabulle, apud me

paucis, si tibi di favent, diebus,

si tecum attuleris bonam atque magnam

cenam, non sine candida puella

et vino et sale et omnibus cachinnis.

haec si, inquam, attuleris, venuste noster,

cenabis bene: nam tui Catulli

plenus sacculus est aranearum.

sed contra accipies meros amores

seu quid suavius elegantiusvest:

nam unguentum dabo, quod meae puellae

donarunt Veneres Cupidinesque;

quod tu cum olfacies, deos rogabis,

totum ut te faciant, Fabulle, nasum.

What the AI produced is not very elegant Latin. It knows to put the verb at the end of the sentence by default. But there are traces of English word order and style translated directly into Latin. ‘Plus … quam ego imaginatus sum’ sounds like English to me. I had to ask it what it meant by ‘Hendecasyllabi ultorem iustitiam tulerunt.’ It obliged by explaining:

“The hendecasyllables have brought avenging justice.”

It implies that the poetic lines themselves (the hendecasyllabic verses) acted as instruments of justice or vengeance against Marrucinus. It adds a mysterious, almost supernatural twist to the story!

But iustitiam ferre is not a thing, per TLL. I think the AI means something like supplicium sumpsit.

On the other hand, maybe I’m missing something, but I see only one genuine mistake: oculos (bolded above) should be oculis. Credetis (also bolded) should probably be creditis, but it’s not an outright error.

I was planning to use this to have the students spot and correct errors, but I really can’t find any other outright mistakes, as opposed to instances of sub-par Latin. Wow.