LIBERI: freeborn, legitimate children (of either sex)

I want you to take a wife to your house so you can produce liberi. (Plautus, Aulularia 148)

You had liberi not just for yourself but for the fatherland, children who could be not just a source of pleasure for you but also who would one day be useful to the state. (Cicero, Against Verres 2.3.161)

Quite a few men are stingy in the raising of their liberi—which were the original objectives of their marriages and prayers—nor do they tend to their education or to the development of their physical faculties. (Columella, On Farming 4.3.2)

You made a contract regarding the manner of your marriage. The writing of that contract rings clear, “for the sake of bearing children” [liberorum procreandorum causa]. Therefore do not approach her, if possible, unless for the purpose of bearing liberi. If you pass this limit, you act against that agreement and that contract. (Augustine, Sermons 278, PL 38.1272.)

Terms of affection for children are not as numerous in Latin as in English, but they include pullus (“chickadee”), parvulus and putillus (“little shaver”), and pupus (“puppet,” “doll”). The most idiomatic and Roman of endearments is pignus. A pignus is whatever one gives as bond or security for a debt, or to assure appearance in court, good conduct, etc. By extension, a person who is a pignus can serve as a “collateral” or “hostage”—for example, in diplomacy between two states. When applied to children, as it sometimes is in epitaphs, in poetry and other emotive contexts, pignora casts them as “sureties” or “pledges” of the love of the parents, assuring the reality of their marriage. But in such contexts it has no legalistic flavor. Often the best translation is simply “dear ones” rather than something more literal, like “little guarantees.”

Liberi is not a term of affection, but, like pignora, it has legalistic roots and lacks any real equivalent in English. It designates children born free (liber) from the legitimate union of a free man and woman. Liberi were the goal of marriage, and raising them properly was seen as a serious responsibility to the state, as Cicero reminds a courtroom adversary. For St. Augustine, they are the only possible reason for having sex. Not spurii (of unknown father), or “conceived promiscuously” (vulgo concepti) from a slave girl, concubine, or courtesan, they were instead certain (certi) and legitimate (legitimi) and provided an indisputable heir. Roman educational advice concerned itself exclusively with liberi, probably on the assumption that other children would be prevented by prejudice from pursuing a public career that was the point of education in the first place. As the Greek writer Plutarch says in this context, “I should advise those desirous of becoming fathers of notable offspring to abstain from random cohabitation with women; I mean with such women as courtesans and concubines. For those who are not well-born, whether on the father’s side or mother’s side, have an indelible disgrace in their low birth, which accompanies them throughout their lives, and offers to anyone desiring to use it a ready subject of reproach and insult.”

The word liberi has a solemn tone that derives from its use in legal and ceremonial contexts, especially in the standard marriage contract. The words liberi and filii are often interchangeable; but in moments of high drama, such as when children were being threatened or dishonored, the solemnity of liberi might be used for emotional effect. “I myself have seen,” says St. Ambrose, “the wretched spectacle of liberi being led off to the auction block to pay a father’s debt, and being kept as heirs to his calamity, though they had no part in his success, and the creditor not even blushing to commit such an outrage.” Another church father says, “You must work hard and take risks in order to keep your children [pignora], your home and your fortunes safe, and to enjoy all the good things of peace and victory. But if you prefer peace now to the hard work . . . your fields will be laid waste, your house plundered, your wife and children [liberi] will become the spoils of war, and you yourself will be captured or killed.” In these passages liberi, with its connotations of legal legitimacy, honorable marriage, and secure inheritance, emphasizes the dastardliness of the moneylender and the threat posed by the enemy. On the other hand, when referring casually to one’s children, it would not be necessary to use a word of such precision, and nati or filii would do.

Filii, as we can see from the French and Italian descendants (figlio and fils), won out in the long run. Liberi seems to have gone out of currency in later Latin, and it left no trace in the Romance languages. Writing in the early seventh century, Isidore of Seville seems not quite to understand it fully when he says, “In the laws, filii are called liberi to distinguish them from slaves.” But of course one could be freeborn without necessarily being a liber in this sense, provided that one’s mother was free. To be a true liber was to be free and also not a bastard.

Given the care with which classical Latin defines the legal status of children, a curious gap in the lexicon is an insult meaning “bastard.” Of the recorded terms, spurius was a rare legalism referring to any child conceived out of lawful wedlock, or one whose father was not known; nothus was the insulting ancient Greek word for bastard, and it is occasionally borrowed by Roman writers. But neither spurius nor nothus ever became a common insult. Illegitimi, while a theoretically possible formation in Latin, is not recorded. Quintilian notes the lack of a good word for bastard in Latin and says that when necessary Romans used the Greek term, nothus. One would think, prone to invective and obsessed with birth and lineage as the Romans were, that spurius would have been a handy stone to throw. But no.

At some point now impossible to determine, bastardus emerged. This mysterious but fertile Romance root yielded Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish bastardo, French bâtard, and passed into all the continental Germanic languages, including English, by the late thirteenth century. But it has no recorded existence in Latin. One theory of the etymology of this non-classical insult says that it comes from the French word bast, as in fils de bast, meaning “son of the packsaddle.” This compares with the British English usage of someone being “born the wrong side of the blanket” or being “the son of a gun” (as in a “shotgun wedding”).

Bibliography: Thesaurus Linguae Latina 7.1301–1304. Plutarch: On the Education of Children 2. Ambrose: On Tobias 8.29. Another church father: Lactantius, Divine Institutes 6.4.15. Isidore of Seville, Etymologies 9.5.17. Quintilian: On the Orator’s Education 3.6.97.

Adapted from the book Ancient Rome in So Many Words (New York: Hippocrene, 2007) by Christopher Francese.

Adapted from the book Ancient Rome in So Many Words (New York: Hippocrene, 2007) by Christopher Francese.

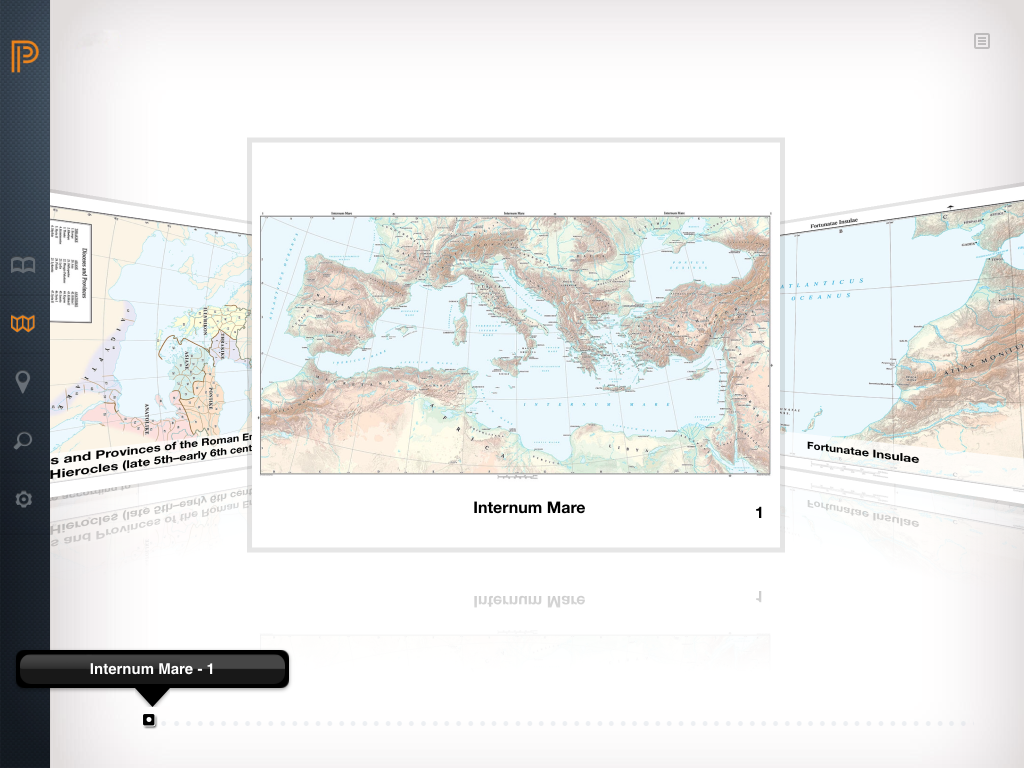

It is often difficult for digital projects to get any detailed critique outside of the grant writing process, or even then. So I was delighted to see

It is often difficult for digital projects to get any detailed critique outside of the grant writing process, or even then. So I was delighted to see