Fighting racism, or any wicked, or simply wrongheaded, idea, ultimately demands attempts at persuasion, person to person. All non-violent activism and efforts at social change depend on rhetoric. It is fashionable now to believe that persuasion—the political kind, anyway—is something of a mirage, that much of our thinking is “motivated,” driven primarily not by argument and evidence but by self-interest, tribal loyalties, enduring personality traits, and demographic facts. Identity comes first; the rationalizations that make us feel that we are correct in our prejudices hobble along after. So argues Ezra Klein, for example, based on many psychological and political science studies, in Why We’re Polarized (2020). The role of the art of rhetoric in this model is not to persuade, but to activate and weaponize identities and their powerful latent drives. Politics in this view is best understood not as reasoned civic dialogue but as a high-stakes all-in partisan combat. Persuasion exists, but as a dog tied to the cart of identity group competition—so say the studies.

Classical authors from Aristotle to Demosthenes, Cicero to Quintilian, understood that the antithesis between identity and reason posed by such focus-group-and-psychological-study-wielding social scientists is entirely false. Common sense chimes in with Aristotle’s Rhetoric, which is really a brilliant exploration of psychology and emotion: persuasion is real, but not entirely rational. Eloquence uses reason and emotion, responds to identity and trades in argument. It is founded on the audience’s predispositions, its prejudices and existing opinions, but lives in the art of the orator. The orator’s moral responsibility as a citizen is significant because persuasion has real consequences, sometimes life and death. And the weapon of demagoguery is always at hand. Virtually every classical historian explores this dynamic, not to speak of the orators themselves and the rhetorically trained and gifted classical poets and dramatists. There is no more central topic in the classical canon than the techniques and ethics of persuasion, and no more burningly relevant aspect of the classical tradition today.

The power, delight, and social utility of eloquence, the universal desire among educated people to possess it, and the perception that the classical texts had unique keys to understanding it, lie behind the dominance of classical Greek and Latin in antebellum educational curricula. Caroline Winterer’s The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Intellectual Life, 1780 -1910 (2002) describes how students were willing to put up with punishing pedagogical regimes of memorization and humiliation to acquire access to the “world of words.” In the pre-industrial economy, classical study was the main route away from agricultural work to professional distinction as a lawyer, doctor, or preacher. But as Winterer emphasizes, the classical texts were not just a toolbox for professional success. They came with a set of values seen as key for maintenance of a republic, values that put checks on self-interest and party passion. Later, as grueling preparation in Greek and Latin proved inessential for success (hello, Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln), the rationale for the classics shifted to their more ineffable aesthetic qualities, the wisdom and inner perfection to be found in the deep study of classical culture. The practical, rhetorical-political rationale for the classics shifted to the background. This inwardly directed self-cultivating focus of the classics as it developed in the later nineteenth century was the legacy of classical teaching to the humanities in modern academy, argues Winterer.

Why not revive the tradition of classics as a route to effectiveness in the world via eloquence, minus the Precambrian teaching methods? Many students are anxious about speaking in public, though they know the ability to do so is valuable for almost every profession, career, or ambition. Despite its importance, public speaking is absent from most college curricula. It falls in the cracks between academic disciplines. Classical studies is well placed to meet this educational need. A judicious selection of classical theory and models, combined with modern insights and examples and abundant practice, will improve students’ skills, deepen their appreciation effective speaking, and help them critique unprincipled persuasion and demagoguery. Perhaps most importantly, it will help them get attention for ideas and causes they care about. Classical texts could help them change the world.

One problem is that classicists don’t consider themselves qualified to teach “speech.” Another is that, for many students, speech carries unpleasant reminders of being forced to watch the greatest hits of American political oratory and encouraged to speak in public in pompous platitudes. Then there is simple ignorance of what classical rhetoric is actually about. The peddling of that trio of abstractions, logos, ethos and pathos—terms dimly understood but somehow profound—and the focus on rhetorical devices (more recherche Greek terms) represent all that is irritating and pretentious in classical teaching. Then again, Aristotle’s Rhetoric is no easy read, and ancient rhetorical manuals are forensic in orientation and remote from the needs of the English language. Unfortunately, modern speech textbooks do little to improve on the pedantry of some of their ancient predecessors.

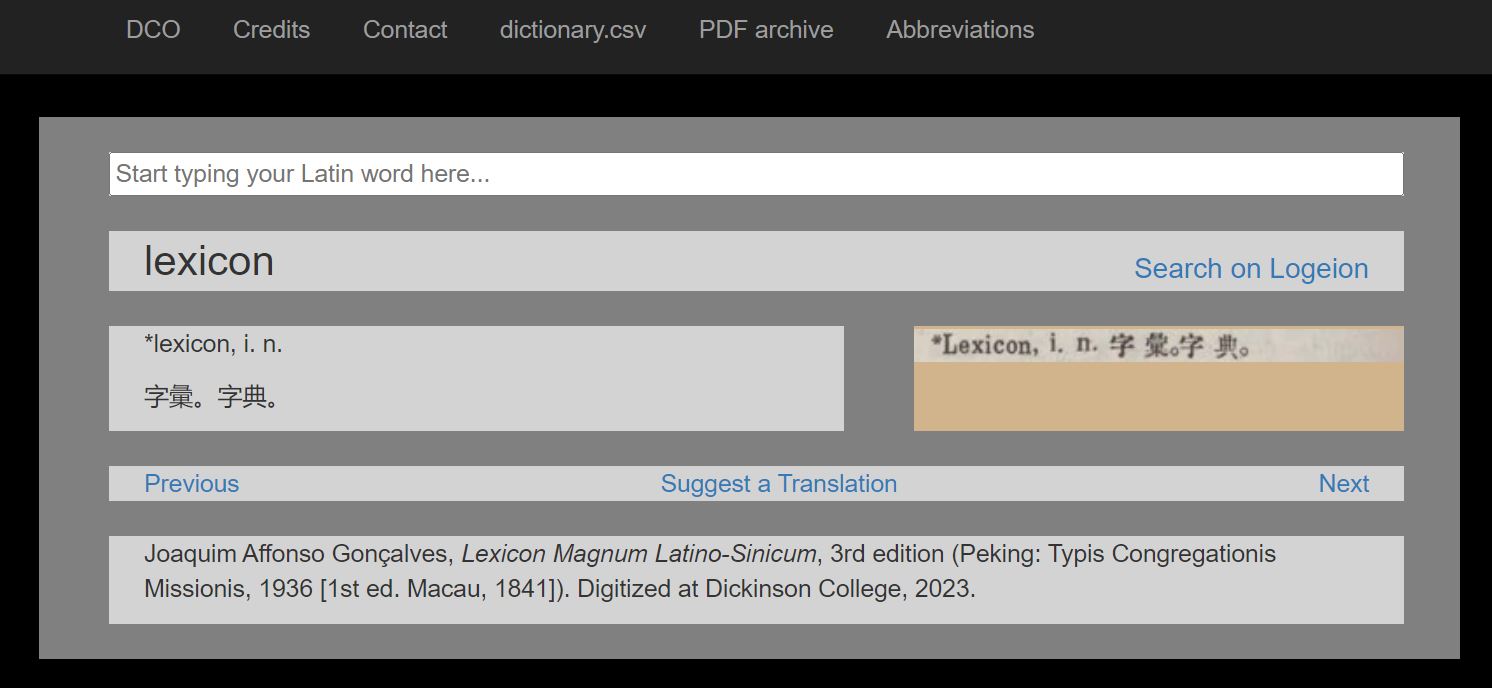

Luckily, materials are starting to become available that could form the basis of a contemporary public speaking class with a classical spin. James May’s How to Win an Argument: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Persuasion (2017) well translates key passages from the oratorical works of Cicero, helpfully introduced and annotated, and (bonus) it includes the Latin texts. Veteran journalist and teacher Roy Peter Clark publishes “x-ray readings” of contemporary speeches, like Greta Thunberg’s UN Speech and Obama’s Philadelphia speech on race, which are essentially classical-style rhetorical analyses without the intimidating verbiage. The Harvard Business Review has for years been publishing brilliant, undogmatic essays on persuasion in a business context, many of them with unacknowledged classical content, such as Jay Conger’s “The Necessary Art of Persuasion.”

One way to avoid the platitudinous reputation of “speech” is to focus on real life rhetorical challenges, like giving a pep talk (Sallust’s Catiline delivers two excellent ones), motivating people to take a looming threat seriously (Demosthenes’ life’s work), or apologizing (Aristotle has excellent advice, Rhet. Book 2, section 3). One can then pair classical precepts with modern examples, which students can find themselves and contribute to the discussion. Ditch logos, ethos and pathos (essentially an analytical framework) in favor for the practical trio of inventio, elocutio, and actio, that is, framing (coming up with arguments to suit a particular situation and audience), style (using memorable language), and delivery. This is Conger’s model, a stripped down, non-forensic version of the classical system. Students tend to be fixated on actio and neglect inventio and elocutio. Conger puts these in balance and adds the insight that an effective persuader/manager must listen as well as talk.

Classically informed analyses of modern speeches, such as Clark’s, or the wonderful essay on Kennedy’s Inaugural by Burnham Carter, Jr.[1] can help to focus attention on tailoring a message to a specific audience and paying close attention to word order, metaphor, sound, clause length, and the like. The classical stylistic criteria of correctness (words in common use, properly designating the things you want to say), clarity (meaning is immediately understandable, avoids excessive abstraction and euphemism), ornamentation (use of tropes and figures to add vitality and polish), and propriety (parts make a whole and the whole fits the occasion) apply to every speech and serve nicely as part of a rubric.

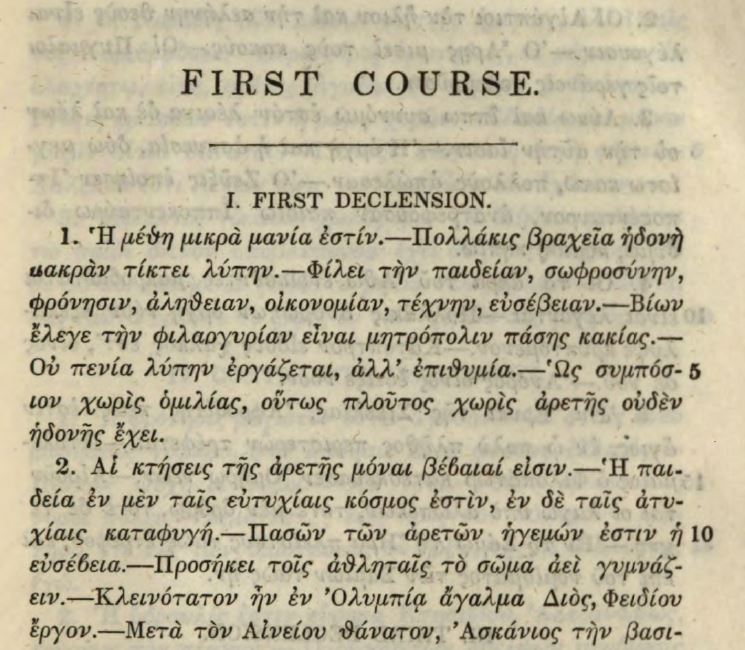

One way to keep the classical content lively is to read about famously high stakes rhetorical moments: the Mytilenaean debate (Johanna Hanink’s How to Think about War: An Ancient Guide to Foreign Policy [2019] excerpts and translates this and all the key speeches from Thucydides), the conspiracy of Catiline, Caesar and the mutiny at Vesontio, Marc Antony at the funeral of Caesar. Truly strong translations of key speeches from classical orators and historians, read aloud and recorded by good actors, would be a great help. Samuel Rowe has made a start by recording the first half of Cicero’s first Catilinarian in a compelling style, though the translation is the nineteenth century one by Yonge.

A syllabus constructed along these lines worked well for me, and the class drew a group more diverse in every way than the ones I teach in a normal classical civilization class. Since some of their speeches were about their own lives, experiences, and interests, I got to know the students better than in any class I have ever taught. Every teacher will have favorite speeches from classical works, so the problem is more one of choice and presentation than of finding suitable material. The balance of ancient and modern, of Aristotle and TED talk, will depend on what the students are ready for. But I am convinced that the vitality of classical rhetoric, its powerful conceptual framework, its ethic of public service, and its stylistic excellence, can speak effectively to contemporary problems and inspire today’s students.

[1] “President Kennedy’s Inaugural Address,” College Composition and Communication 14 (1963), 36–40.

Patrick J. Burns is Associate Research Scholar for Digital Projects at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University, working previously at the Quantitative Criticism Lab at the University of Texas at Austin and the Culture, Cognition, and Coevolution Lab at Harvard University. Patrick is working an online book to be titled

Patrick J. Burns is Associate Research Scholar for Digital Projects at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University, working previously at the Quantitative Criticism Lab at the University of Texas at Austin and the Culture, Cognition, and Coevolution Lab at Harvard University. Patrick is working an online book to be titled