Yes- I guess we unanimously agree that the National Portrait Gallery was filled with portraits of the white and wealthy. There were no representations of middle or lower class, or any people of color, which didn’t come as a surprise to me. If you weren’t royalty or didn’t have a consistent money flow, you most definitely had no chance of getting your portrait done; hence no people of color. I was however pleasantly surprised with the amount of portraits of women- I expected it to be much less. There were a number of beautifully depicted portraits of women in intricately designed gowns that probably made every woman wonder what it would be like to have been in their shoes. As I began to take a closer look at each woman’s face, I noticed a similar characteristic; a majority of them were extremely pale and emotionless. After a while, I began to realize they all had to same face and the only things that differed were the color of the background, hairstyle, and attire.

As I was just about getting fed up with seeing identical miserable portraits, I came across a portrait of Mary Moser by George Romney in 1770

.

(Taken from the National Portrait Gallery)

Mary was an English painter and one of the most celebrated women artists. Very popular in the 18h century, Mary was known for her depictions of flowers and had been recognized as an artist since the young age of 14. I was thrilled to see a woman who was an individual and tapped into her own talent to make a living, instead of sitting upon hereditary wealth. Romney did an excellent job in captivating Mary doing what she loved while expressing the happy look upon her face. So in the end, I didn’t walk out of the National Portrait Gallery completely disappointed as I envisioned.

Tags: 2010 Melissa · Uncategorized

September 6th, 2010 · 4 Comments

I went to the British Library today to get a library card and begin research. In the two hours I spent there I acutely encountered an English phenomenon that Professor Qualls has described. I suppose I would call it ‘the run around.’ It is a fairly backwards system in which nothing can be accessed directly or simplistically acquired. At every turn this system required another step or was made more complicated or forbade me from receiving normal library benefits. The miserable experience began when I tried to get a library card. I had a passport sized photo and the letter from the University of East Anglia so one would think this process would be simple. And one would be wrong.

First, I had to fill out a list of the books that I would be getting out. Let’s, you and I, reader and myself, take a moment to consider this task. Here I am, setting foot in this library for the first time. I plan on searching through the databases and selection of books to find something worthwhile for research. However, before I have done so, I am obligated to say which books I will be using. While clearly I can just fudge a few names onto the page and say these are the ones I’ll be using, the idea behind the request seems to only serve as an impediment to a process that should be quite simple.

So I fudge the titles, finally get the card after a solid half hour of pure, cool, wasted life and head over to the Humanities section. From there, I’m redirected down to a bag section where I wait in a queue in order to put my backpack in a closet. Why this section was not outside the area I was not allowed into with it remains a mystery. Moving on, I was told that certain books were being kept in Yorkshire and for that reason are only available to be ordered for forty-hours later, which is perfectly understandable. However, when I ordered my books not marked as being kept in Yorkshire, I received a figurative swift kick in the pants. To receive any book from anywhere in the library takes seventy minutes. For effect, I’ll repeat that. Seventy minutes. Yes, that is for any book. Seventy minutes.

Why couldn’t I go up directly to someone working at the Library, ask them where the book was, and retrieve it in, say, 15 minutes? Perhaps because that would be too easy and too simple. Perhaps because the Brits are afraid of direct contact. Or perhaps it is because they take a sick pleasure in watching people go up and down escalators getting progressively more cranky and hungry! But I put that behind me, and said, well, I’ll just wait the seventy minutes and take my requested book out and look at it tonight after dinner, because I was preposterously famished at this point, as I hadn’t anticipated the hundred (70+30) minute process I would encounter before even looking at my first source. At this point, The British Library hit me one final time, delivering a knockout blow. I was informed that you cannot check books out. That’s not a typo nor an exaggeration, folks, you really can’t. I’m not just yankin’ the ol’ chain there. So, in a huff, I left, vowing never to return.

Until tomorrow when my books arrive.

Tags: 2010 Michael

September 6th, 2010 · 3 Comments

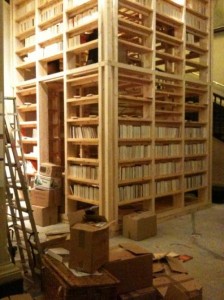

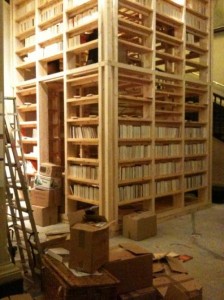

When going to the Victoria and Albert Museum the first rule is: do not get a map. It is completely useless. It will only make you more confused (if that is at all possible). The Victoria and Albert is like no other museum I’ve ever been to. Instead of the sparse but well cataloged rooms of the British Museum or the abstract instillation art of the Tate Modern, there is just “stuff.” It feels as if one has stumbled into a very eccentric, very wealthy old man’s closet. There is a vague sense of organization, but the curator has not stuck to a strict order. Instead one is assaulted with a variety of priceless artifacts. To top the disorganization of the rooms is the disorganization of the building itself. The rooms flow into one another like a maze. From the moment I walked in I should have known that it was going to be a completely new experience — immediately outside of the tube station there was an exhibit filled with treasures that would have been centerpiece at many smaller museums. I then continued into the fashion exhibit which was filled with a barrage priceless vintage clothing from across the world. From there we went through the sculpture hall to the one piece that I felt summed up the museum as a whole: a book tower. It was a multi-storied wooden structure just filled with a random assortment of books — everything from romance novels to Chaucer to Russian literature. This disorganization and jumble of priceless and random books should have been an indicator that my day was about to get a lot more impressive.

(courtesy of http://www.vam.ac.uk/things-to-do/blogs/11-architects-build-small-spaces)

(courtesy of http://www.vam.ac.uk/things-to-do/blogs/11-architects-build-small-spaces)

The madness of the Victoria and Albert reached its pinnacle in the Medieval and Renaissance section where upon a cursory browsing I stumbled upon a little journal tucked away behind a wall. This journal was not accompanied with any great display or paired with a painting or some other artifact — it stood on its own. This unassuming little book turned out to be a Da Vinci journal. If it had not been for the presence of a gold plaque indicating that it was something special I would not have even read the explanation. However, it was a room full or gold plaques and priceless artifacts and it was a completely fluke that I stopped and looked. From this point on, I just gave up. I was too incredulous to take the Victoria and Albert seriously. In a world where small local museums are starving for artifacts the Victoria and Albert have so many that they just cannot display them to their full potential. I personally wish that the Victoria and Albert would loan out items to eliminate the clutter and share their wealth. This would make the museum less overwhelming and it would allow more people to view more fascinating treasures.

Tags: 2010 Amy · Museums · Uncategorized

When I visited the National Portrait Gallery the other day, I was pretty bored by the Tudor and Stuart portraits. If only we had portraiture of the ‘true lives’ of those figures rather than just stuffy, formulaic paintings. However, I was much happier when I finally got to the meat of the museum and started to see some literary and philosophical heavy hitters pictured. When we went on our Bloomsbury walk, I enjoyed hearing about the lives of the many interesting people who’ve lived here. It was neat to go one layer deeper at the Portrait gallery and see some portrayals of the society we’d heard about. In particular, I found a painting by Augustus John of Lady Ottoline Morrell. (Exhibit A):

#mce_temp_url#

The caption informed me that Lady Morrell was a socialite who entertained the likes of Aldous Huxley at her home in Bloomsbury. I was initially attracted to the photograph for its unattractiveness. Ms. Morrell seems to have some serious defect of the mouth in this portrait. A search of the NPG’s collections reveals two facts about Ms. Morrell’s likeness. First, the portrait I saw hanging in the gallery was accepted in lieu of taxes by Her Majesty’s government in 1990 and subsequently given to the gallery. Second, the Augustus John portrait is one of several hundred portraits of Lady Morrell which the museum holds (I got to page 6 of 60 of portraits before I stopped looking). None of the other portraits seemed to show the same deformed mouth as this one. And this, the one portrait with the markedly unattractive feature was the painting chosen for inclusion in the gallery. Curious.

I next came to a portrait of Aldous Huxley which showed him as a young man. Beneath the painting was a caption which informed me that Huxley had written the collection of essays, The Doors of Perception, while on mescaline. Fun fact there. Here’s the portrait of Huxley…. (Exhibit B):

#mce_temp_url#

All of this made me wish I could have been hanging around Bloomsbury during the days of Woolf, Huxley, and Morrell. Of course, they probably wouldn’t have let me in….

Tags: 2010 Daniel · Museums

September 6th, 2010 · 1 Comment

John Elliot Burns, whose portrait was painted by John Collier, was a labor leader in the late 19th and early 20th century. He was also the first member of the working class to be elected to a cabinet.

photo courtesy of NPG website

In the piece, Burns has his hands on his hips and a somewhat contemplative yet subtly stern expression. To me, the hands-on-hips symbolizes his discontentment with the conditions for the working class of London, those whom he led as a labor leader. This is a classic position of humans to show malaise. The angle of his head and raised eyebrows seem to suggest a bit of a “what of it” attitude. To some degree, these features balance his bodily position. If he were to have a furrowed brow and straightened head, he may appear too antagonistic to those he was trying to persuade (members of parliament, etc.). The profound facial features reinforce his strength of character, with defined cheek bones and dark eyes, beard, hair, and eyebrows. His beard also makes him look older and more experienced in life.

Lastly, the relatively simple suit, shirt, and tie combination shows that he is not a man of superfluous extravagance. This simple attire reflects the plain dark brown background. As opposed to many of the other portraits in the galleries, where many posed in front of extravagant rooms, by the lake, or the countryside. Burns was not one for such extravagance, or at least he was not portrayed in this portrait as such. This again helps reinforce the idea that he was a man working for increased rights for laborers, a man of the people.

Overall, I think this is a great portrait that casts Burns as a strong man working for workers’ and laborers’ rights.

As to who was and was not in the gallery, as everyone else has concluded: it is primarily rich white people. To me, this makes quite a bit of sense. For the vast majority of British history, older affluent white people have been in power, subjugating the rest of everyone else. I find it highly unlikely that any of these aforementioned people thought “wow, I should really get a portrait painted of my lowly dockworkers, that would be a great piece for that national portrait gallery one day.” In no way do I endorse the absence of a wider variety of people. Though getting later into British history, i.e. after the mid 19th century when there has been less rampant subjugation, yes, there should have been more portraits included of other races/economic classes.

However I’m not quite sure who to blame for this. I believe (I may be wrong) that the vast majority of the portraits were done privately and then donated to the museum. These portraits are probably quite expensive to have painted, and thus most could not afford them for quite some time. Perhaps certain groups of people simply choose not to have their portraits done, even if it has become lately feasible for them. I feel like portraiture has certainly become less popular over the past century, which may explain the absence of the groups of people who have lately gained rights/power/money/etc. recently. Though I find it unlikely, another possible explanation is that perhaps the curators have many portraits featuring minorities and simply choose not to display them. I certainly hope that is not the case.

Tags: 2010 ChristopherB

My favorite painting from the gallery is a portrait of Ben Jonson. A playwright and poet of the Jacobean era, Jonson received some distinction with the works Bartholomew Fair and The Alchemist, both of which I have not read – and for good reason. Unlike his contemporary, Shakespeare, Jonson has completely fallen off the map, having none of the distinction and prestige of his fellow bard. Jonson, as it were, is not “canonical.” In any case, Jonson’s poor rep didn’t prevent me from enjoying his portrait. Indeed, an interesting point about portraiture is that there seems to be a sort of discrepancy between the the artist and the subject. Take for instance the portrait of Shakespeare. Our interest lies with the subject, Shakespeare, and not the artist. Conversely, in Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet we are interested in the fact that the painting’s author is Van Gogh, and less so by the fact that the painted figure was someone called Gachet. And of course other times, the interest is mutual – Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Its interesting to note how the discrepancy lessens as you go further through the timelines in the gallery. The Tudor, Stuart, and Jacobean rooms are very much indicative of the British brand of class system and ideology. But as you reached the portraiture of the early 20th century, you find friends drawing each other (i.e. Bloomsbury group).

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The artist who painted Ben Jonson’s portrait is Abraham van Blyenberch, a flemish artist of whom I know little about and care even less. Yet I found it to be one of the most original portraits in the gallery, rivaling that of the ones of Tennyson and Sir John Fieldings. Instead of the traditional rigidness we’ve come to expect from the Renaissance, Blyenberch’s Jonson is refreshingly relaxed. He looks slightly bemused, his head tilted just enough so that it conveys a sense of contentedness and ease. Even so, the portrait still relates to the viewer an august demeanor, probably due to the variations of bronze in the background, hair, and face. When I first looked at the work, I immediately thought of Rembrandt; Jonson’s beady, penetrating eyes echoes that of the psychic dimension of the Dutch master’s self portraits. Although Rembrandt would create his most famous pieces almost a generation later, the style we associate with that region seems to be diminutively intuited by Blyenberch. Through this portrait of Jonson, we are able to look beyond the British stiff upper lip.

Tags: 2010 Sean · Museums

As a college student in this day and age, the 21st century, certain aspects or principles of life tend to be on my mind like every other student in America. Specifically I ponder whether my future career will have worldly riches at the forefront or intellect and the communities well being. As my young mind tries to figure this out I was caught off guard in the National Portrait Gallery, in the section of the museum that is labeled “The Tudor Dynasty”. As this title suggests the majority of these portraits were of Kings and Queens and nobility ranging from King Edward II to King Edward VIII. However, among all these nobles and riches sat a man by the name of Sir Thomas Chaloner.

Sir Thomas Chaloner, unlike any of the other Tudors in that room, was not born into greatness but instead earned it, through sheer determination and the use of an insightful mind. He was a statesman, one of the first England ever saw. He served under four different Tudors, was knighted after participating in the war against the Scots in 1547; he is best remembered as the first English translator of Praise of Folly. Besides having such an amazing and extensive resume, what caught my attention was what I saw within his portrait. Just as I ponder about what my life will say about me, so did Sir Thomas Chaloner ponder the same question five centuries ago. However, he was able to find an answer. His portrait depicts him in a frontal view with a very unwelcoming facial expression. In his hand he has a scale; on one side there is gold and the riches of the world on the other lies a stack of blazing books that outweigh the “transitory nature of earthly treasures.” Above him is a Latin inscription that refers to the Assyrian King Sardanapulus’ realization on material riches, “they fade black and begrimed with soot as though gold were nothing else but smoke…” ( You may find more information on the portrait at http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw01174/Sir-Thomas-Chaloner?search=ss&firstRun=true&sText=Sir+Thomas+Chaloner+&LinkID=mp00823&role=sit&rNo

Although I know Sir Thomas Chaloner, like the majority of humans, had many faults I commend him for devoting the intelligence he did gather for the improvement of society. I only wish to take the privileges I have received so far and will receive in the future to improve our 21st century society in one way or another; whether it be helping a child understand their homework , or having an active part in legislation. Only time will tell if I achieve this, in the meantime I will keep searching for my own answer.

Tags: 2010 Jamie

September 6th, 2010 · 5 Comments

I visited the Tate Modern this week determined to disprove my growing suspicion that modern art is an Emperor’s New Clothes type hoax designed to make me look like an idiot. Unfortunately, the first time I visited I only had half an hour. So I rushed through a floor of splattered paint and a white room filled with off white canvases that, according to Agnes Martin, were supposed to represent “weightlessness and infinity” rather than the possibility that the museum staff had run out of white paint.

Then I came back a few days later when I had more time, and as luck would have it the first exhibit I came across was Art & Language by Michael Baldwin and Mel Ramsden with the promising description that “viewers are now confronted by themselves, thereby questioning a long-held notion of painting transcending reality.” I understand that some art is supposed to be philosophical, but it was a mirror on canvas, which makes it the exact equivalent of that scene in my favorite childhood movie, Neverending Story (costarring a delightful dragon puppet) in which the main character has to face himself in a metaphorical mirror to save the land of Fantasia. Obviously the best movie ever created, but not art. It made me angry.

So I went through the next few rooms with the mirror as a yardstick for my expectations and found the following pieces:

- Giuseppe Penone’s Tree in 12 Metres (two trees in a museum)

- Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s Untitled (some guy’s messy garage in a museum)

- Keith Arnatt’s Self Burial (a bunch of pictures time elapsed pictures of a guy sinking in quick sand)

I list these pieces because they were really underwhelming until I looked at them a second time, and they turned into basically the coolest things ever. The Tree in 12 Metres was actually two perfect trees shapes carved out of a giant block of wood. Every messy garage item was a replica carved, textured and painted with polyurethane foam and acrylic paint (this includes an old rubber tire, an unvarnished wooden bench with knots, and a bunch of other distinctly textured items). The time elapsed photographs interrupted a TV program once a day in sequence showing for 5 seconds without any explanation.

I’ve been seeing this pattern everywhere, and I feel like the British must have a huge penchant for Easter eggs. The Bloomsbury walk was covered in historical landmarks that I always thought were a huge deal. In the United States, Virginia Woolf’s house would at least be a small museum as opposed to the small plaque next to an otherwise occupied building. The Victoria and Albert Museum was a whole other level of hidden amazing things. Along with a novelty bustle that plays God Save the Queen every time the wearer sits down (classy), one of DaVinci’s notebooks, marked in tiny writing, was sitting in a random corner (The other five of his notebooks that the museum has are just in storage right now. No big deal). Do they just have so much history here that they have to ignore some of it so as not to turn the country into a museum? Or does that obsession with understatement that Kate Fox talks about seep itself all the way in British history so that they hide their great achievements in a corner out of amusement and feigned modesty? It seems so contradictory to what I would expect from a former empire. I expect neon signs. Not that I’m complaining. I don’t think I would get this excited about a foam tire replica under any other circumstances.

Tree of 12 Metres

(Giuseppe Penonoe) from Tate.org

Tags: 2010 Jesse

September 6th, 2010 · 2 Comments

Friday night, I stopped into a pub to watch the evening’s football match as the England national team embarked on their quest to put their World Cup misery behind them and qualify for the European Championships in 2012.

As England took the field, faces around the pub were not filled with joy, but with scepticism. There were not cheers of “Come on England,” but groans that perfectly relayed to me as a foreigner how the footballing nation had been feeling all summer since its agonizing 4-1 exit at the hands of Germans two months earlier. In the team’s first competitive match since the world cup, the squad knew they had to perform. The day’s headlines in the sports section highlighted the importance of getting the team a strong win; for, although England faced easy opposition in the qualification round, the patience of their fans was drawing thin.

In the Three Lions’ previous game, a friendly against Hungary, fans booed. Similarly, this summer in South Africa, after drawing 0-0 against a meagre Algeria side, fans booed. And, as was made blatantly obvious by the regulars at The Rising Sun, at kick off, they were not pleased with their Three Lions. What is even more peculiar than the fan’s dissent is the England players’ tolerance for them. After England’s dismal exit from World Cup in June and even preceding the team’s friendly against Hungary players consistently came forth to defend their fans’ right to boo.

After noticing this odd characteristic of criticism toward the national side, I asked the two stalwart England fans I had been chatting with throughout the match as to why fans felt entitled to judge and criticise England’s form and results. The two blokes, Rory and Paul, both asserted their right to be critical, but noted a few crucial limitations. Paul said, “I am English, and England has always been my home. When football is this important, as it is in England and the rest of the world, they represent all of us, our country and the way we live. You never boo England before any competitive match, only friendlys, but you can boo after any pathetic result, such as the 4-1 loss to Germany.”

It is this element of entitlement and right of opinion present in English football that I have noticed many other places in English culture. In the Museum of London, an exhibit catered to this same form of entitlement of opinion, asking Londoners pertinent questions on how London should be managed, raging widely from what type of construction should constitute London to how many trees should be planted. Unlikely as it was that the exhibit influenced any official opinion, yet there was far from a scarcity of opinions, again underscoring the general right of the English to voice their concerns and protect and preserve Englishness.

This entitlement of opinion, I feel, is linked with the same protectionist sentiments of “English National Identity” that we have encountered frequently in our readings. The right to be critical, the right of opinion and the right to preserve are all intensely imbedded into Englishness. Whether it be the fear of England’s national team letting down the nation, or the nation changing into something disastrously un-English, the English feel entitled to voice their opinions and protect against these changes.

These ideas are unequivocally absent in America. We seem to define and pride ourselves as being a “melting pot” and that our national identity is a lack of one specific set of ideals or social norms. We feel that being a diverse nation of all races and backgrounds is in fact who we are, whereas the English staunchly believe in specificity of Englishness.

It will be interesting to study during my year how these notions of entitlement and protectionism influence, uphold and define Englishness, what it means to be English and the right and privileges pertaining thereunto. During this year, I want to discover what compiles Englishness and how this protectionism functions within its society.

Tags: 2010 Luke · Uncategorized