September 11th, 2010 · 2 Comments

While visiting the British Museum several nights ago, I noticed an interesting behavior exhibited by different ethnic groups, depending on the culture focused on in a given room. The exhibits that I was looking at that particular evening (Ancient Greeks and Ancient Asians) were rather diverse, and it was precisely this diversity that alerted me to this phenomenon. While wandering through room after room of Greek artifacts, I noticed that Asian visitors (with only very few exceptions) would pass through these rooms without stopping to actually look at many, if any, of the artifacts. I slowed my pace considerably through the remainder of the exhibit, to observe the most number of people, and sure enough, Asian visitor after Asian visitor passed through the rooms, only occasionally stopping to look at one artifact, or more likely, take a picture, before moving on. Compared to visitors who looked to be of European/American ancestry, the difference is stark. These people generally took their time through the exhibits, stopping to gawk at an exceptional pot or other artifact, and generally going at a more suitable pace for such a wonderful museum (in my opinion).

Intrigued by this, I moved on to the Asian exhibits to see if I could find a similar trend there. Sure enough, I did, but it was almost completely reversed. In this case, the Asian visitors were the ones that were slowing down to look at everything, while the people that were zipping through were almost entirely Caucasian. This is exactly what I expected to find, as my hypothesis prior to entering the Asian room was that people, whether consciously or subconsciously, care more about cultures closest to their own, and are therefore more interested in the history of these cultures. This is why those of Euro-American heritage took their time through the Greek exhibits, but zoomed through the Asian room, while the Asians exhibited the opposite behaviour.

All this may either be evidence for or against the British Museum. This small, unscientific experiment of sorts seems to show that people don’t care about other cultures, at least not as much as their own. It’s very easy to extrapolate this to all sorts of things (for example, various imperialist wars in the Middle East, religious intolerance all over the world, etc.), but I don’t want to make this post too upsetting, so I won’t dwell on sad things, and get back to the Museum. I’d rather think that this phenomenon shows that the Museum has something for everyone. No matter where you’re from, you’ll find a piece of our history at the British Museum. I’d like to think there’s a bit of hope left in the world, so I thoroughly believe that this latter theory more true than its predecessor.

Interestingly, to finish things off, I travelled to the Americas section of the museum to see what kind of demographics it attracted, to compare to my observations in the Greek and Asian sections. I found that no one, no matter who they were or what they looked like, just buzzed through. Everyone was transfixed by the Native American headdresses and canoes, but I found no Americans in the exhibit (It’s surprising how easy we are to pick out, once you live in another culture for a while). This seemed exactly contrary to my other findings, as going off of my findings, you would expect to see a whole gaggle of Americans in the part of the museum dedicated to their history. On closer inspection however, this makes perfect sense. The vast majority of Americans are not of any measurable Native American descent. Instead, we’re predominantly from Europe and Asia, which incidentally are the exhibits in which I found all the “missing” American visitors. This “exception” seems to in fact further prove the rule, as Americans, as part of a “melting pot,” still associate closely with the history of their international forefathers.

Tags: 2010 MatthewM · Museums

September 11th, 2010 · 2 Comments

London’s diverse museums all have an element of British imperialism. The three which best show this are the Wallace Collection, the Sir John Soane Museum, and the British Museum. Yet, each takes a different approach to them: the British Museum is the standard artefact with didactic label, the Soane shows the spoils of an imperialistic age in the wonderful cabinet of curiosities method, and the Wallace Collection arranges its collection as a wonderful combination of the two.

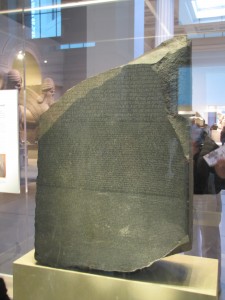

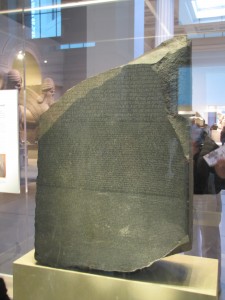

The Rosetta Stone, which has been a centerpiece of the Egyptian repatriation demands.

We’ll start with the British Museum. Perhaps the most controversial collection because of the Elgin Marbles, most of the collection could probably be at the center of a repatriation argument if a government decided to challenge the museum. Instead of noticing that the museum was a shrine to British imperialism, my first thoughts (once I pulled myself away from the medieval galleries) were about the museum’s role in the ongoing battle over countries reclaiming their artefacts. My general beliefs on repatriation are simple: the works belong wherever they are going to get the best care, which, unfortunately for the vast majority of the ancient objects, is not in their countries of origin. For example, there is no way that Egypt can assume responsibility for its antiquities; the ones there are deteriorating alarmingly. While Hawass has done a good deal for Egyptian antiquities, their facilities still are nowhere near those of the British Museum’s facilities. Furthermore, shouldn’t objects that have influenced the whole of history be where the most people have access to them? Surely that is here, in London, not in Cairo?

One of the Elgin Marbles

Unfortunately, that argument is no longer valid for the Elgin Marbles (although, while not as an unpredictable environment as Egypt, Greece does have its problems which could threaten the marbles). Greece has a new acropolis museum that is a perfectly suitable house for the marbles. So, why do I still believe they belong in London? Aside from the whole no-objects-can-leave-England-law and the incredible galleries they are currently housed in, there a couple of reasons. Firstly, their provenance, unlike that of the Italian krater the Met repatriated to Italy, shows them to have been purchased legally versus outrightly stolen. We may not agree with the way they were handled in the 19th century, but because we have a different understanding of the proper way artworks should be sold/purchased does not mean we can go back and make amends with everything. The world’s great museums would be emptied. Secondly, where they are now, they are more accessible. If Greece didn’t have almost as many as the BM, I’m sure everyone would feel differently about the issue. (Well, except for Greece, which would still demand them all, even in the BM only had one.) Because repatriation has become such an important issue, I do believe that even if English law did not forbid it, the marbles would never go back to Greece because once the BM accepts Greece’s arguments, the watershed for repatriation will be open and museums will be scrambling to quadruple check their works’ provenances, possibly wasting valuable resources.

It was only after my second visit to the British Museum that I wondered about some of the works’ provenances. However, from the moment I stepped into the Sir John Soane, all I wanted to do was demand to see some of the provenances of various works, as well as pick up the objects to examine them and the way that they were removed from their original locations. I think part of the reason that it took a second visit to the BM to question it was as one of the leading museums in the world, it has more authority as the stellar, but smaller, Soane. The traditional layout of the BM commands respect, whereas the Soane is easy to mistake for a pile of junk haphazardly arranged. Except, it is the exact opposite: the Soane has incredible pieces. (I could have died of joy looking at the random Gothic bits.) Because of the arrangement- a life size cabinet of curiosities- it is easy to forget that all of the works can point to the achievements of Soane and his time, noticeably imperialism. When walking through, one’s mind is trying to take in everything and is not assisted by didactics, the larger picture is sometimes lost, unlike at the BM, where the layout and didactics remind you almost constantly that while the museum is “British”, the majority of the collection is not. Furthermore, the Soane’s arrangement allows one to feel closer to the objects. Indeed, it is easy to get away with a close examination of the work on the wall and touching them. In the BM, the viewer is often annoyingly separated from the work by class or a rope barrier.

If the BM is arguably the most controversial museum because of its collection, then the Soane is the most overlooked for controversy. Lots of the works were supposedly removed from crumbling sites. Were the sites crumbling before or after the works were removed? Did the dealers have explicit permission? These questions are largely overlooked; in fact, lots of information is overlooked, which adds to the feel of a cabinet of curiosity.

The Wallace Collection

The Wallace Collection is like the Soane in that it started as one cohesive collection and has grown, as well as that it shows the way the works were staged by their original collector. However, unlike at the Soane, the Wallace Collection does an amazing job of showing lots of works in a way that is not as overwhelming. The collection is mostly housed in period rooms, which add to the atmosphere of the museum, greatly enhancing the works. Instead of wondering about whether the objects should be repatriated, the collection sets up the works in such a way that the viewer is not distracted by theoretical questions on museum practices. (Unless said viewer gets bored of Rococo and armour.) Furthermore, the collection focuses on European art, which focuses it a bit more than the other two museums. If anyone is interested in armour, the Wallace’s collection is superb and world-renowned. Instead of wandering around the museum pointing to works I wanted to examine for causes to repatriate, I wandered the Wallace wondering why certain works were hung together and why anyone would want rooms upon rooms of Rococo art, much less why I was wondering around them when there were three outstanding armouries downstairs that were calling me.

Yet, part of me wonders if Britain didn’t have it’s imperial past, would I be able to see this quality of art and artefacts. If I were able to, would I wonder about the provenance and history of each work as much?

Tags: 2010 Stephenie · Museums

September 11th, 2010 · 1 Comment

Throughout our time here so far, I’ve been to museums that I’ve loved and loathed. Regardless of how I felt about the collections, each museum seemed to say something about England, as well as demonstrate amazing educational programs. (I’ve decided to tackle the issue of museums in two separate blogs. I’m not going to deal with repatriation and provenance, both issues have been on my mind a good deal at a couple of the museums, most noticeably the British Museum and the Sir John Soane museum, in a second blog. This one will be more general and focus a bit on educational programming within the galleries.)

Firstly, thinking back to over two weeks ago, the Greenwich Observatory was an interesting museum. It wasn’t one of my favourites, partly because of the collection, most of which I did not really care for. However, the excellent interactive bits throughout the exhibits were engaging. It did a good job explaining the importance of Greenwich time and it’s relationship to the development of shipping. (I probably know more about longitude now than I ever needed to know.) Unlike the other museums I’ve visited, the achievements it highlighted, were an integral part of the build-up to imperialism vs the spoils of imperialism.

Prime Meridian

The Tate Modern would be my next least favourite. I like some modern art, but it is not normally my first choice to spend an afternoon admiring. (Unless it is a Kandinsky show.) Throughout the Tate, I felt that some of the space had been wasted, especially on the floor where the membership room was located. The main galleries were nice, but offered very little in terms of supplemental didactic materials that could further engage the viewer- all of that was outside of the gallery. While the interactive bits were very interesting, they could easily distract from the art itself. (The seemingly endless reel of video shorts seemed to confirm this.) Yet, I admired the activities for the younger children which engaged them and put the art on their level. By separating the modern art from its other collections, the Tate seems to promote its standing: it is worth more than a gallery add-on in the main building.

The Tate Modern

The Guildhall Art Gallery, by comparison, offered very little interactive displays. By the time I had visited here, I was so use to in-depth descriptions, a wide audience, crowded galleries, and fun didactics, that the seemingly empty gallery caught me off guard. It was nice to see the Roman Amphitheater; the room’s set-up was incredible with recreations of the gladiators. However, the gallery’s art collection was lacking. It mostly seemed to be lesser works of second-tier artists or smaller copies of major artworks created later in an artist’s career. I believe that the gallery was trying to show the positives of British art in the last 200 years, but the gallery failed in this mission because it failed to hold one’s attention for long. Furthermore, the special exhibitions were too text panel heavy. (Balance seems to haunt this gallery.) The panels were informative, but when 3/4 of a panel is devoted to reproducing a picture which is hanging next to the panel, there is a problem. The viewer is drawn to the reproduction, not the actual artwork, defeating the point of the gallery.

The National Gallery is one of my favourites that I have visited, partly because of the Wilton Diptych and partly because there is one spot where my favourite Holbein and a Vermeer are both in one’s line of sight. The collection is outstanding and the works seem to represent the majority of art history. Well, my favourite bits at the very least. While there are not as many interactive activities, the didactics are engaging and there are educational options available. Instead of only seeming to be the spoils of imperialism, the collection has a truly British feel, partly because so many of the works are ones that directly relate to English history rather than the history of far off places. Furthermore, it’s easily accessible and not hidden like the NPG; it’s prominent position on Trafalgar Square also helps with accessibility.

The Wilton Diptych

(For more information: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/english-or-french-the-wilton-diptych)

The Victoria & Albert would be tied for my second favourite museum thus far with the National Gallery and the British Museum (which I’ll discuss in my other museum post). I spent almost 2.5 hours in the new Medieval and Renaissance Galleries, which were not only gorgeous, but held some incredible pieces. (Can I please just have one grotesque figure?! Just one…) Several people have noted that the sheer amount of stuff in the museum is overwhelming. Outside of the M&R Galleries, I would agree with this. Here, the museum seemed to be addressing this issue, trying to open up the galleries and spread out some of the pieces. Furthermore, the excellent listening stations found throughout the galleries were a perfect mix of in-depth and cursory information, allowing the viewer to pick and choose the information they heard based on their interests. (Highlight: listening to Gregorian chants while viewing the different altarpieces, all of which were stunning.) The V&A proudly displayed artworks which combined to tell the story of the world through art. Unlike the British Museum, it did not claim to be a solely British institution, which I think in some ways helped make the museum a more open place. Furthermore, because it is an artistic school as well, it’s collections are all educational, adding to a different responsibility for its didactics and what is should be collecting. It filled gaps through its amazing replicas gallery, which included some of the most famous works ever created.

Misericord, Victoria & Albert

When taken together, the museums not only provide one of the most stellar examples of museum education in practice, but also serve to tell the triumphs of the British Empire and to highlight the triumphs of the larger artistic international tradition. If London is a city of the world, then its museums reflect this.

Tags: 2010 Stephenie · Museums

September 11th, 2010 · 3 Comments

As you probably all already know, I come from a really big family. For my time in the UK, that means SOUVENIRS. By the truckload. Seriously, I won’t be surprised if I have to check an extra suitcase just full of trinkets to bring home to my parents, siblings and cousins. Pretty much everywhere we go, I look through the gift shops to see if anything grabs my attention. So far, I’ve collected novelty mugs, decks of cards, pens, pencil sharpeners, magnets, Christmas ornaments…and I’m not even halfway done.

So after all this time spent in the gift shops, I’m starting to notice a few patterns. It goes without saying that the kitschier the gift shop, the more touristy the location. I mean, I doubt that many actual Londoners (outside of elementary school students on field trips) visit the Tower of London, just like I doubt many Londoners would want the beaded Union Jack change purse I bought my sister in the gift shop there. How many people who actually live in Stratford want overpriced chocolate with Shakespeare’s face on it when they could just go to Tesco? How many people who actually live in Bath want Christmas ornaments of Roman soldiers, or leather bookmarks with a gold embossed likeness of the baths on them? I think by this point we can all stop a tourist trap – or at least a tourist destination – a kilometer away.

On the other hand, we’ve seen some gift shops that don’t seem to cater directly, or exclusively, to out-of-towners. Take the V&A, for example. It’s full of fun jewelry and stationary and other knick-knacks that don’t scream “I WENT TO THE V&A.” A lot of the gifts focus on the art displayed in the museum, rather than reminding us of the museum itself. The National Gallery is the same way – greeting cards and tea pots with prints on them, coffee table books centered around a particular artist – Monet, for example – rather than the content of the collections. Its gifts, in short, aren’t just advertisements. The British Museum was the most interesting of all – it has sections for many of the nations the museum represents. I’m serious. You can buy sequined notebooks and pens from “India.” You can buy colored pencils in sarcophagus-shaped tins from “Egypt.” On the one hand, these items aren’t really “souvenirs” – nothing about them suggests that you went to England and all your little brother got was this lousy [fill in the blank]. This suggests that the museum expects to get a lot of traffic from Brits, if not Londoners themselves. (Could there be a class issue here, as well?)

As a sidenote, is it just me or is it a little disturbing that the British Museum gets to profit off tacky trinkets they designed after the priceless artifacts they’ve copped from the same countries they’re now selling these trinkets in the name of? Whatever. I guess what I mean is , it’s interesting to see which of London’s historical sites are at least as much for British citizens as they are for tourists. By my estimation, I’d say the National Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery, the V&A, the Tate and the British Museum expect to cater to many Brits. Appropriate, since they’re all subsidized. And since they have the most valuable and, in my opinion, the best collections of any of the sites we’ve been to, I guess this is just more evidence that Brits have good taste.

Tags: 2010 MaryKate · Museums