Entries from September 2010

September 14th, 2010 · 4 Comments

The other day I went with a few others to the Newman House up the road from Arran House to attend Catholic mass. On the whole I think we all enjoyed the experience and actually gained a lot from it. For me, it was a relief to finally hear a native Englishman discuss the role of Catholicism in England, a topic I’ve been curious about even before coming to London.

Briefly looking around at the number of university students congregated in the small chapel, the priest quickly recognized that most were foreign to England. I could not tell whether or not his decision to touch on prominent hot button religious issues was planned. Regardless, the priest took advantage of preaching to the variety of students about contraceptives, abortion, homosexuality, and the global fear of Catholicism. Obviously they’re quite heavy, controversial issues to discuss in just a twenty-minute sermon.

Although the priest’s explanation of the Catholic Church’s view regarding homosexuality was particularly intriguing—and positive—, I was most interested in his discussion regarding the presence of Catholicism in England. He described the underlying sense of fear of Catholicism and the Papacy among the English. The priest made comments alluding to the English people’s standoffishness toward practicing Catholics and the Church on the whole. The discord among Anglicans and English Catholics apparent today may be incomparable to the country’s history but the unease among the English is still faintly visible. The priest at one point joked that the English fear the Papacy in Rome and devout Spanish Catholics will some day return to England to convert everyone back to Catholicism.

From my experience touring Westminster Abbey, St. Paul’s Cathedral, a Hindu mandir, Jewish synagogue, and Islamic mosque, and attending Catholic mass in a small university chapel, I have realized a subtle controversial religious dialogue materializing in London. England has an established church but their reaction to religious diversity is much different from America’s where no church is established. There is a fear of Catholics worldwide, but where I live the religion is thriving and accepted (again, that could easily be just because of my location in the northeast). I think religion is part of an American’s cultural identity but also one’s spiritual faith is more strongly expressed, whereas in England, Anglicanism easily becomes just a label. As Kate Fox described: a child once asked their parent what their religious background was, and the parent told the child to mark Anglican. When the child questioned this decision, the parent stated that that’s just what one was supposed to put. Furthermore, as the gentleman at the synagogue explained today, it would be unwise for a candidate for Prime Minister to publically share their religious beliefs, whereas in the United States, a politician’s religious devotion is widely broadcast. Although both nations continue to struggle with religious tolerance and freedom, I would say I feel more comfortable as Catholic in America than in England. I receive opposition in America, but I also feel free to defend my beliefs. Here in England, even people’s spiritual devotion to the established church is diminishing; completely ignoring the fact that Catholicism’s presence is seemingly minimal. Although my experience at the Newman House was most definitely positive, I look forward to finding a larger community of Catholic students at UEA in Norwich (hopefully).

Tags: 2010 Mary · Churches and Cathedrals

September 14th, 2010 · 3 Comments

We’ve already talked about the elitism that we’ve seen in museums such as the National Portrait Gallery and the National Gallery, and I’m sure that everyone has at least a passing familiarity with the debate over the Elgin Marbles. (If not, Stephenie wrote a small book about it a few days ago, so just keep scrolling down the page.) I don’t want to beat the imperialism theme over the head too much, so I’ll try to take a different angle here. What has struck me about so many of the museums that we’ve visited has been the vast collections of stuff housed within their walls. Isn’t this the point of musuems? you might ask. Well, yes. But I feel like the size of the collections and the way that they are displayed here just screams “materialism” more loudly than any museum that I’ve visited previously.

Apart from the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum is the best example of this. The array of exhibits in this museum is incredible–everything from fashion to theatre, jewelry, micromosaics, sculpture, medieval art, and every silver dish ever manufactured in the British Empire. Wandering through (the floor plan made absolutely no sense to me, so I just walked around), my eyes started to glaze over because of the sheer number of artifacts displayed. In the silver rooms, for instance, there were cases packed so tightly with pieces that there was not enough room for display cards; interested viewers had to pick up a card that was chained to the outside of the case. And underneath all of these cases, which took up a pretty substantial area, were drawers full of more pieces that didn’t fit in the displays. It was insane. The V&A had some amazing pieces, but the opulence and materialism on display there were astounding.

Although some of the other museums that I visited were much smaller and were actually house museums, I noticed this same glorification of materialism. The Sir John Soane Museum is a wonderfully eccentric home that Soane, a nineteenth-century architect, designed specifically to hold his collection of artifacts and his “cabinet of curiosities.” It’s really neat to walk through and see all of the peices that he has hiding in the nooks and crannies of his home (one room has extendable walls that fold out from the permanent walls. There are currently sketches by J.M.W. Turner that are displayed on these hidden walls). His collection includes several pieces of Greek and Roman statues, wonderful works of art by Hogarth and Canaletto, and even an Egyptian sarcophagus. But again, I got the sense that there were just so many things packed into such a small space. And I had to wonder, like Stephenie, how he came by all of these treasures and why he needed a room full of Roman busts. It seemed as though he had collected all of these things simply because he could. Thankfully he had the foresight to turn his home into a museum so that his collection would be accessible to the public to come and learn from it, but the thought still lingered. The Wallace Collection left a similar feeling, although a large portion of the collection housed there comes from other parts of Europe.

I firmly believe that these huge, opulent collections are only possible because of Britain’s imperial past. They had access to so much of the world, and they had the power and the weapons to take artifacts from all of these places (even if the Elgin Marbles were supposedly sold legally). As the strongest nation of the nineteenth century, Britain was able to amass all of the silver found in the Victoria and Albert Museum, and all of the pieces of sculpture housed in the Soane. The money was there and the artifacts were ripe for the taking, so materialism (and I think fascination with exotic cultures, especially with the Orient) naturally followed. I’m not trying to say that this is right or wrong, and Americans as a whole definitely value the consumer and material wealth. It’s just what has really struck me from the museums that I’ve visited.

Tags: 2010 Holly · Museums

September 14th, 2010 · 4 Comments

Last night at Barclays Wealth was the first time I have ever been to an event where I was expected to mingle with rich, important people with one of my intention being to network for possible jobs (the other being to represent my school and my program, but I’ll get to that). I felt I was supposed to get dressed in formal clothing (painful shoes, scary make-up processes, scary hair frying devises) so I wouldn’t stick out as someone that didn’t care about the program, and it was kind of stressful. I recognize that a lot of people like dressing up, and that is great (they were super helpful and made it way less stressful). But I don’t like dressing up. I rarely dress up, and when I do, I’m really uncomfortable. I also have no idea how to network. I’m perfectly happy talking to strangers, but I don’t know what any of the social customs are for that particular type of event. The fact that I was wearing fancy, uncomfortable clothing leads me to believe that I am not expected to act like myself even though that is what I expect a person’s advice would be if I asked them directly. Otherwise I would being wearing normal clothes, the clothes I wear when I am expected to be myself. There are unwritten codes of conduct and a change in clothing and appearance denotes that those codes need to be enacted. I don’t think anyone could overtly tell me what those codes are because they are codes that you only learn through practice, and people that know them are unconscious of them because they seem natural.

This brings me to class. We’ve been spending all this time talking about how class in England is so weird because it’s based on habits and lifestyle choices when in America it’s mostly just a tax bracket thing. I really think we’ve been exaggerating this difference quite a bit. Class in America might be about tax brackets once you get there, but if you want to get rich, you probably need a sweet job, and if you want a sweet job, you probably need to be good at mingling with rich, important people. People from lower classes in the United States and in England alike do not get the same opportunities as the upper classes to practice mingling and all the social customs that go along with it (being comfortable in fancy clothes, which hand to hold your drink in, the best hand shake, how to politely find important people, what subjects are taboo, what jokes are okay, how coarse to get with language, how to gracefully enter and leave a conversation, how much criticism of society is acceptable and what part are off limits, how to show off without seeming like a jerk, etc.).

As a disclaimer, I’m not trying to paint myself as a victim and say that class limited me here. The fact that I’ve never had to look for a real job and that I just don’t like wearing fancy clothes limited me, but that is expected because I am young. But that experience of being really uncomfortable brings to my attention that there is a huge difference in social customs. Dickinson gave me this opportunity, and I’ll be better at it next time. What about people who just don’t get this opportunity in the first place?

For America, it’s the same thing we hear over and over again. The American Dream is a myth that propels itself by a handful of people who actually make it. People from lower classes have the deck stacked against them in more ways than one and the rich have just hte opposite. For England I think it’s a little more complicated, and I invite anyone to put their two cents in because I’m still trying to work it out myself. If England has a more rigid class system in which people take pride in their working class characteristics, how do they learn the social customs necessary to network and make more money? How can we even say that England has a rigid class system if Kate Fox says that middle classes have so much class insecurity that the use of bizarre upper class sounding, French terms are now characteristic of middle classness? If class in England is really not about money and success, is it the ends to some English equivalent to the American Dream?

Tags: 2010 Jesse

September 14th, 2010 · 5 Comments

As someone who is fairly religious I have spent a large amount of time in London contemplating religion – something that I think many of us have done and which is a large theme in our course. Thus far I have been to the building of or attended a religious service in a mandir, a mosque, a Catholic mass, evensong at St. Paul’s, and after today, a synagogue. As a practicing Catholic, I expected to feel very at home at both the Catholic service I attended and evensong (given how many similarities there are between Anglicanism and Catholicism). However, even sitting through a mass that I have sat through every Sunday for the last 20 years I felt completely alien. While the format of mass was the same and prayers were the same, the level of participation and tone of the homily were unlike anything I had ever experienced.

On Sunday, when Mary, Mary Kate, Jamie, and I walked two blocks to the Newman House I had pretty low expectations as to what mass would be like. The mass put on at Dickinson every weekend is quick, easy, and low on congregational participation. Back home in California, my church puts a large focus on intellectual exploration of scriptures and does not discuss controversial issues. Instead, on Sunday I attended a service where everyone was active and where I heard an extremely rousing and inspiring homily. The priest completely ignored the gospel for the day (which was the famous tale of the prodigal son) and discussed the upcoming papal visit, general English views of Catholicism, homosexuality, and the previous mistakes made by the Catholic Church. The priest discussed the lack of positive press about the Catholic Church in England and tied that to the English fear of popery – he even made continual jokes about how the English still see the Spanish armada sailing across the Channel to turn them all back to Catholicism. He then spent a long time discussing homosexuality – a topic that never EVER came up in my more conservative Church (which is ironically enough considered very liberal among Catholics in the area). He said that it was unacceptable and sin to denounce anyone, including members of the LGBT community. He argued that just because we are Catholic we are not allowed to hate or discriminate. He stemmed his next point off of this idea – he said that we should not look at the Catholic Church as infallible. He made the point that we cannot pretend that the priest abuse scandal didn’t happen and that we must admit that the Catholic Church mishandled the debacle. His over reaching message, however, was tolerance, acceptance, and education about Catholicism.

The idea of education leading to tolerance and acceptance has been the general message of most of our visits to religious institutions. Both the mandir and the mosque were exercises in religious education and both of our guides spent a lot of time discussing religious doctrine and the need for understanding about different religions. In the face of all the religious discrimination and controversy surrounding both the building of a mosque near where the Twin Towers once stood and the minister threatening to burn Korans in Florida in the United States, its refreshing and reassuring to know that somewhere in the world there is religious dialogue occurring and several different faiths are trying to bridge gaps and end violence and discrimination.

Tags: 2010 Amy · Churches and Cathedrals

September 12th, 2010 · 4 Comments

I can’t begin to imagine the amount of beer cans that were picked up off the streets of Notting Hill after that gigantic parade/fair that I visited at the beginning of the program. Everyone was drinking as they followed the floats (if you call reggae DJ’s riding on big buses floats) down the streets of the neighborhood, throwing their beers on the ground as they were receiving a joint from a generous hand or reaching into their pockets for two pounds to purchase a sketchy jello shot. The side walks were engulfed in the trash that overflowed behind the jerk chicken and Bob Marley tee shirt vendors. Though it sounds dirty, which I guess it was, it was a unique (not going to say fun) experience. First off, I don’t think I’d ever seen saw many people in one spot in my entire life. I was nearly crushed to death so many times. I also liked some of the costumes that the paraders were wearing. I didn’t really like the costumes themselves, women in feather decorated bikinis, but they represented the enthusiasm that so many people had for this event. I soon got tired of it all though, and after trying to get through the crowds of drunk and high people, the closed subway stations just got me even more frustrated.

But the Thames Festival! It was like a five year olds birthday party compared to what I went through at Notting Hill. Like the previous festival there were vendors, but here there were much more and they offered a lot of different foods and crafts. It wasn’t exclusive to one neighborhood, so people were selling everything from Greek food, to pizza and from Japanese, to sweet and tasty churos. Lots of vendors sold toys, like bubble makers and glow wands, while other offered paintings and clothing. As I walked along the shore of the Thames, under the London Eye, I moved through the foot traffic easily and listened to a concert that was off on the grass close by. The paths along the river were busy, but there were no traffic jams. There were people holding clear plastic cups of beer, but that was really the extent of the drinking. I didn’t notice anyone that I thought was wasted. Anyway, the big event of the night were the fireworks. I found a spot on the bridge next to the London Eye and waited half an hour for the fireworks to start. Sadly, I was on the wrong side, and blocking my view of the show were the steel supports for the train track that ran through the middle of the bridge. From what little I saw, but more from the “ohs” and “ahs” of the huge crowd watching, I assume the fireworks were incredible. The tube station and the bus stops were remarkably uncrowded, so the trip back home took as long as it would any other day.

-

-

Two different experiences, one a little more comfortable than the other, but both well worth attending. The Thames Festival, if it happened every weekend I would go. For the Notting Hill Festival, I think once every three to four years would be okay.

Tags: 2010 David · Uncategorized

September 12th, 2010 · 6 Comments

I’ve always been a moderately healthy eater. I try to stay clear of junk and fast food as much as possible. However, leading a healthy lifestyle can put quite a dent in your pockets in the states, especially if you don’t have the time to cook. This is the exact reason why so many people in the U.S. don’t eat as healthy as they should, especially in big cities and urban communities. In a fast pace environment, convenience plays a big role in deciding what to eat for lunch; basically whatever is prepared to grab and go. For example, this summer I worked on Fifth Avenue in New York City, which is always bustling with people no matter what day of the week it is. The allotted time for my lunch period ranged from thirty to forty five minutes, which sounds like a decent amount of time but by the time I made my way through the swarms of people on the streets, waited in line and ordered my food, and then hustled back to the break room, I barely had fifteen minutes left to actually eat my lunch. For the first couple of weeks, I would get lunch from PAX Wholesome Foods, which serves healthy sandwiches, drinks and other snacks. A small sandwich would run me about seven to eight dollars, and then I would have to buy a drink and sometimes fruit. I would end up spending around thirteen to fourteen dollars and would end up being not being completely satisfied taste-wise and hungry again in an hour or two. Once I began to calculate how much money I was spending on food, plus transportation to work all week, I realized I was spending almost half of a weeks’ paycheck. Unfortunately, I couldn’t do anything about the price of transportation, so I had to cut down on how much I was spending on food, which led to the occasional trips to McDonalds (yuck!).

Once in England, it wasn’t as difficult to eat healthy on the go. I have never consumed so many sandwiches in the course of two weeks. There are a number of healthy outlets scattered throughout London. A couple of us have designated the chain EAT: The Real Food Company, as our favorite lunch spot. EAT would be the slight equivalent to the PAX chain that I mentioned before, except richer in variety and quality, and more accessible with locations everywhere! Dedicated to fresh food, all of EAT’s sandwiches are handmade daily and baguettes are baked every morning, which PAX didn’t do. The sandwiches vary between 3 to 5 pounds, depending on content, and taste really good! It would be impossible to find a place in NYC that freshly prepared food daily and was this affordable. Planet Organic is also another venue that has captured my heart and taste buds. It’s quick, affordable and sooo delicious (it deserves the extra o’s). My favorite lunch, which is a filling serving of their mixed vegetable soup with complementary bread and butter and a 1.5L of water and sometimes a blueberry muffin, runs me less than five pounds. I’ve never been supermarket shopping, but from what I’ve heard there are also healthy and reasonably priced items as well. I feel that here in London the money that I spend on food goes a much longer way than it does back in New York. I am able to eat right and still have money left for dessert!

Tags: 2010 Melissa · Uncategorized

September 12th, 2010 · 3 Comments

I’ve been fascinated by the effects of alcohol ever since I read The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in my freshman year, the same time I was introduced to college drinking social norms. By day students go to class and make self-aware, well thought out comments and criticisms of society, and by night drink and do all manner of scandalous things to gossip about in the morning (obviously not everyone, but a sizeable portion). We’ve been talk about the British social dis-ease, but I wonder if American social customs are really all that different.

Kate Fox notes that our expectations of alcohol’s effects are cultural rather than purely biological (261). England is known for its aggressive drunks and that expectation, and possibly a little national pride, is a self fulfilling prophecy. As the drunk insane asylum manager from everyone’s favorite show, Bedlam, says as he stumbles around the stage, “We’re English. It’s what we do” to which the audience responded with a proud cheer. For whatever reason, boisterous drunkness is a major source of identity for England, even if it’s also a symptom of the inability to socialize without a lubricant to put you in a liminal state. As a result, while Latin American countries associate alcohol with more peaceful states, England gets bars in Covent Square Garden that forbid the wearing of football colors to prevent bar fights.

I’ve tried to visit a few different types of pubs, and I’ve found so far that no matter the atmosphere, the clientele, or even the level of drunkenness, when it comes to alcohol the Brits are not the friendliest bunch (You see what I did there? Understatement. I’m so assimilated). I’ve managed to get over the occasional obvious refusals of service when pubs close at an oddly specific time if they see a group of five Americans coming toward them. The slightly more expensive pubs I’ve gone to have not been as bad. I usually just get a server who refuses to make any form of polite small talk or eye contact with me, unless he is joining in the group glare that I often receive from everyone in the room when I speak, stand in the wrong place, or exist. The younger, louder pubs were pretty nice because fewer people could hear my accent and it was too loud for me to hear angry throat clears. Unfortunately, the minute I got outside, a few drunk men took it upon themselves to fix that by yelling obscenities and telling me to go back to America (In their defense, I think I might have offended them when I was praising the benefits of Razor Scooters as they walked past. Hot button issue).

During the day, besides the occasional angry glare when I use my 6 inch voice instead of my 4 inch voice in the library, people have been generally friendly, which leads me to believe that Fox is right about the British extremes in behavior. They’re excessively mild and polite (Jekyll) until they drink a potion that makes them grow fur on their hands and have a strong desire to beat me to death with a cane.

Tags: 2010 Jesse

September 11th, 2010 · 2 Comments

While visiting the British Museum several nights ago, I noticed an interesting behavior exhibited by different ethnic groups, depending on the culture focused on in a given room. The exhibits that I was looking at that particular evening (Ancient Greeks and Ancient Asians) were rather diverse, and it was precisely this diversity that alerted me to this phenomenon. While wandering through room after room of Greek artifacts, I noticed that Asian visitors (with only very few exceptions) would pass through these rooms without stopping to actually look at many, if any, of the artifacts. I slowed my pace considerably through the remainder of the exhibit, to observe the most number of people, and sure enough, Asian visitor after Asian visitor passed through the rooms, only occasionally stopping to look at one artifact, or more likely, take a picture, before moving on. Compared to visitors who looked to be of European/American ancestry, the difference is stark. These people generally took their time through the exhibits, stopping to gawk at an exceptional pot or other artifact, and generally going at a more suitable pace for such a wonderful museum (in my opinion).

Intrigued by this, I moved on to the Asian exhibits to see if I could find a similar trend there. Sure enough, I did, but it was almost completely reversed. In this case, the Asian visitors were the ones that were slowing down to look at everything, while the people that were zipping through were almost entirely Caucasian. This is exactly what I expected to find, as my hypothesis prior to entering the Asian room was that people, whether consciously or subconsciously, care more about cultures closest to their own, and are therefore more interested in the history of these cultures. This is why those of Euro-American heritage took their time through the Greek exhibits, but zoomed through the Asian room, while the Asians exhibited the opposite behaviour.

All this may either be evidence for or against the British Museum. This small, unscientific experiment of sorts seems to show that people don’t care about other cultures, at least not as much as their own. It’s very easy to extrapolate this to all sorts of things (for example, various imperialist wars in the Middle East, religious intolerance all over the world, etc.), but I don’t want to make this post too upsetting, so I won’t dwell on sad things, and get back to the Museum. I’d rather think that this phenomenon shows that the Museum has something for everyone. No matter where you’re from, you’ll find a piece of our history at the British Museum. I’d like to think there’s a bit of hope left in the world, so I thoroughly believe that this latter theory more true than its predecessor.

Interestingly, to finish things off, I travelled to the Americas section of the museum to see what kind of demographics it attracted, to compare to my observations in the Greek and Asian sections. I found that no one, no matter who they were or what they looked like, just buzzed through. Everyone was transfixed by the Native American headdresses and canoes, but I found no Americans in the exhibit (It’s surprising how easy we are to pick out, once you live in another culture for a while). This seemed exactly contrary to my other findings, as going off of my findings, you would expect to see a whole gaggle of Americans in the part of the museum dedicated to their history. On closer inspection however, this makes perfect sense. The vast majority of Americans are not of any measurable Native American descent. Instead, we’re predominantly from Europe and Asia, which incidentally are the exhibits in which I found all the “missing” American visitors. This “exception” seems to in fact further prove the rule, as Americans, as part of a “melting pot,” still associate closely with the history of their international forefathers.

Tags: 2010 MatthewM · Museums

September 11th, 2010 · 2 Comments

London’s diverse museums all have an element of British imperialism. The three which best show this are the Wallace Collection, the Sir John Soane Museum, and the British Museum. Yet, each takes a different approach to them: the British Museum is the standard artefact with didactic label, the Soane shows the spoils of an imperialistic age in the wonderful cabinet of curiosities method, and the Wallace Collection arranges its collection as a wonderful combination of the two.

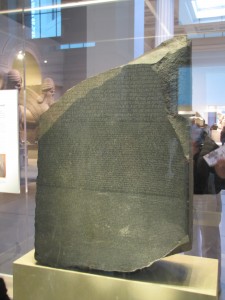

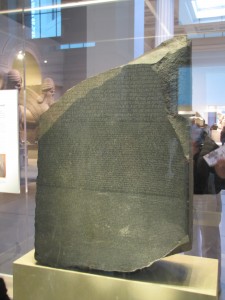

The Rosetta Stone, which has been a centerpiece of the Egyptian repatriation demands.

We’ll start with the British Museum. Perhaps the most controversial collection because of the Elgin Marbles, most of the collection could probably be at the center of a repatriation argument if a government decided to challenge the museum. Instead of noticing that the museum was a shrine to British imperialism, my first thoughts (once I pulled myself away from the medieval galleries) were about the museum’s role in the ongoing battle over countries reclaiming their artefacts. My general beliefs on repatriation are simple: the works belong wherever they are going to get the best care, which, unfortunately for the vast majority of the ancient objects, is not in their countries of origin. For example, there is no way that Egypt can assume responsibility for its antiquities; the ones there are deteriorating alarmingly. While Hawass has done a good deal for Egyptian antiquities, their facilities still are nowhere near those of the British Museum’s facilities. Furthermore, shouldn’t objects that have influenced the whole of history be where the most people have access to them? Surely that is here, in London, not in Cairo?

One of the Elgin Marbles

Unfortunately, that argument is no longer valid for the Elgin Marbles (although, while not as an unpredictable environment as Egypt, Greece does have its problems which could threaten the marbles). Greece has a new acropolis museum that is a perfectly suitable house for the marbles. So, why do I still believe they belong in London? Aside from the whole no-objects-can-leave-England-law and the incredible galleries they are currently housed in, there a couple of reasons. Firstly, their provenance, unlike that of the Italian krater the Met repatriated to Italy, shows them to have been purchased legally versus outrightly stolen. We may not agree with the way they were handled in the 19th century, but because we have a different understanding of the proper way artworks should be sold/purchased does not mean we can go back and make amends with everything. The world’s great museums would be emptied. Secondly, where they are now, they are more accessible. If Greece didn’t have almost as many as the BM, I’m sure everyone would feel differently about the issue. (Well, except for Greece, which would still demand them all, even in the BM only had one.) Because repatriation has become such an important issue, I do believe that even if English law did not forbid it, the marbles would never go back to Greece because once the BM accepts Greece’s arguments, the watershed for repatriation will be open and museums will be scrambling to quadruple check their works’ provenances, possibly wasting valuable resources.

It was only after my second visit to the British Museum that I wondered about some of the works’ provenances. However, from the moment I stepped into the Sir John Soane, all I wanted to do was demand to see some of the provenances of various works, as well as pick up the objects to examine them and the way that they were removed from their original locations. I think part of the reason that it took a second visit to the BM to question it was as one of the leading museums in the world, it has more authority as the stellar, but smaller, Soane. The traditional layout of the BM commands respect, whereas the Soane is easy to mistake for a pile of junk haphazardly arranged. Except, it is the exact opposite: the Soane has incredible pieces. (I could have died of joy looking at the random Gothic bits.) Because of the arrangement- a life size cabinet of curiosities- it is easy to forget that all of the works can point to the achievements of Soane and his time, noticeably imperialism. When walking through, one’s mind is trying to take in everything and is not assisted by didactics, the larger picture is sometimes lost, unlike at the BM, where the layout and didactics remind you almost constantly that while the museum is “British”, the majority of the collection is not. Furthermore, the Soane’s arrangement allows one to feel closer to the objects. Indeed, it is easy to get away with a close examination of the work on the wall and touching them. In the BM, the viewer is often annoyingly separated from the work by class or a rope barrier.

If the BM is arguably the most controversial museum because of its collection, then the Soane is the most overlooked for controversy. Lots of the works were supposedly removed from crumbling sites. Were the sites crumbling before or after the works were removed? Did the dealers have explicit permission? These questions are largely overlooked; in fact, lots of information is overlooked, which adds to the feel of a cabinet of curiosity.

The Wallace Collection

The Wallace Collection is like the Soane in that it started as one cohesive collection and has grown, as well as that it shows the way the works were staged by their original collector. However, unlike at the Soane, the Wallace Collection does an amazing job of showing lots of works in a way that is not as overwhelming. The collection is mostly housed in period rooms, which add to the atmosphere of the museum, greatly enhancing the works. Instead of wondering about whether the objects should be repatriated, the collection sets up the works in such a way that the viewer is not distracted by theoretical questions on museum practices. (Unless said viewer gets bored of Rococo and armour.) Furthermore, the collection focuses on European art, which focuses it a bit more than the other two museums. If anyone is interested in armour, the Wallace’s collection is superb and world-renowned. Instead of wandering around the museum pointing to works I wanted to examine for causes to repatriate, I wandered the Wallace wondering why certain works were hung together and why anyone would want rooms upon rooms of Rococo art, much less why I was wondering around them when there were three outstanding armouries downstairs that were calling me.

Yet, part of me wonders if Britain didn’t have it’s imperial past, would I be able to see this quality of art and artefacts. If I were able to, would I wonder about the provenance and history of each work as much?

Tags: 2010 Stephenie · Museums

September 11th, 2010 · 1 Comment

Throughout our time here so far, I’ve been to museums that I’ve loved and loathed. Regardless of how I felt about the collections, each museum seemed to say something about England, as well as demonstrate amazing educational programs. (I’ve decided to tackle the issue of museums in two separate blogs. I’m not going to deal with repatriation and provenance, both issues have been on my mind a good deal at a couple of the museums, most noticeably the British Museum and the Sir John Soane museum, in a second blog. This one will be more general and focus a bit on educational programming within the galleries.)

Firstly, thinking back to over two weeks ago, the Greenwich Observatory was an interesting museum. It wasn’t one of my favourites, partly because of the collection, most of which I did not really care for. However, the excellent interactive bits throughout the exhibits were engaging. It did a good job explaining the importance of Greenwich time and it’s relationship to the development of shipping. (I probably know more about longitude now than I ever needed to know.) Unlike the other museums I’ve visited, the achievements it highlighted, were an integral part of the build-up to imperialism vs the spoils of imperialism.

Prime Meridian

The Tate Modern would be my next least favourite. I like some modern art, but it is not normally my first choice to spend an afternoon admiring. (Unless it is a Kandinsky show.) Throughout the Tate, I felt that some of the space had been wasted, especially on the floor where the membership room was located. The main galleries were nice, but offered very little in terms of supplemental didactic materials that could further engage the viewer- all of that was outside of the gallery. While the interactive bits were very interesting, they could easily distract from the art itself. (The seemingly endless reel of video shorts seemed to confirm this.) Yet, I admired the activities for the younger children which engaged them and put the art on their level. By separating the modern art from its other collections, the Tate seems to promote its standing: it is worth more than a gallery add-on in the main building.

The Tate Modern

The Guildhall Art Gallery, by comparison, offered very little interactive displays. By the time I had visited here, I was so use to in-depth descriptions, a wide audience, crowded galleries, and fun didactics, that the seemingly empty gallery caught me off guard. It was nice to see the Roman Amphitheater; the room’s set-up was incredible with recreations of the gladiators. However, the gallery’s art collection was lacking. It mostly seemed to be lesser works of second-tier artists or smaller copies of major artworks created later in an artist’s career. I believe that the gallery was trying to show the positives of British art in the last 200 years, but the gallery failed in this mission because it failed to hold one’s attention for long. Furthermore, the special exhibitions were too text panel heavy. (Balance seems to haunt this gallery.) The panels were informative, but when 3/4 of a panel is devoted to reproducing a picture which is hanging next to the panel, there is a problem. The viewer is drawn to the reproduction, not the actual artwork, defeating the point of the gallery.

The National Gallery is one of my favourites that I have visited, partly because of the Wilton Diptych and partly because there is one spot where my favourite Holbein and a Vermeer are both in one’s line of sight. The collection is outstanding and the works seem to represent the majority of art history. Well, my favourite bits at the very least. While there are not as many interactive activities, the didactics are engaging and there are educational options available. Instead of only seeming to be the spoils of imperialism, the collection has a truly British feel, partly because so many of the works are ones that directly relate to English history rather than the history of far off places. Furthermore, it’s easily accessible and not hidden like the NPG; it’s prominent position on Trafalgar Square also helps with accessibility.

The Wilton Diptych

(For more information: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/english-or-french-the-wilton-diptych)

The Victoria & Albert would be tied for my second favourite museum thus far with the National Gallery and the British Museum (which I’ll discuss in my other museum post). I spent almost 2.5 hours in the new Medieval and Renaissance Galleries, which were not only gorgeous, but held some incredible pieces. (Can I please just have one grotesque figure?! Just one…) Several people have noted that the sheer amount of stuff in the museum is overwhelming. Outside of the M&R Galleries, I would agree with this. Here, the museum seemed to be addressing this issue, trying to open up the galleries and spread out some of the pieces. Furthermore, the excellent listening stations found throughout the galleries were a perfect mix of in-depth and cursory information, allowing the viewer to pick and choose the information they heard based on their interests. (Highlight: listening to Gregorian chants while viewing the different altarpieces, all of which were stunning.) The V&A proudly displayed artworks which combined to tell the story of the world through art. Unlike the British Museum, it did not claim to be a solely British institution, which I think in some ways helped make the museum a more open place. Furthermore, because it is an artistic school as well, it’s collections are all educational, adding to a different responsibility for its didactics and what is should be collecting. It filled gaps through its amazing replicas gallery, which included some of the most famous works ever created.

Misericord, Victoria & Albert

When taken together, the museums not only provide one of the most stellar examples of museum education in practice, but also serve to tell the triumphs of the British Empire and to highlight the triumphs of the larger artistic international tradition. If London is a city of the world, then its museums reflect this.

Tags: 2010 Stephenie · Museums