Author- Ruled from 1894- 1917, during his rule there were many military encounters (loss of the Russo- Japanese War, World War I involvement that caused 3.3 million Russian deaths), during his rule the 1905 Revolution occurred which created the 1906 Russian Constitution known for limited the power of the monarchy and instating the Duma, violence towards those politically opposing him (ex. supporters of 1905 Revolution)

Tag Archives: Russia

The Code of Law of 1649

The Ulozhenie, or the Code of Law of 1649, illuminates the immense strength of the Russian government at this time. We read the first several chapters, on blasphemy and improper behavior in church; respect for the Sovereign; forging documents; forging money; and travel to other countries. Each section describes violent and physical punishments for people who fight or disagree in church or who plot against the Sovereign. These laws show not only a regimented society, but also a strong and organized one. By the middle of the seventeenth century, the Russian government had very specific procedures regarding legal documents; standardized forms of money; and clear, indisputable land boundaries.

Analyzing this document in regards to the Sudebnik of 1497 and the Pravda Russkaia of the eleventh century, I am most interested in the section on counterfeit money. The Sudebnik, 150 years before, included laws about blaspheming the church and even land boundaries, but the Ulozhenie is the first code I’ve seen which mentions money. The law dictates, “If mint masters should make either copper, or tin, or economical money…or if they should add copper, tin, or lead to silver and thereby cause harm to the Sovereign’s treasury, such mint masters should be executed by puring molten matter down their throats” (Ulozhenie). Violent and terrifying punishment aside, this act demonstrates that the “Sovereign’s treasury” was composed of silver, and that the common currency was also pieces of silver. Copper and tin were not valid forms of currency; the state had a standarized money system. Furthermore, the tsar understood that corrupting that system could severely disrupt the economics of the country–hence the brutal punishment for the counterfeiter.

This point, however, makes me wonder how widespread this currency was. The presence of a law does not mean that its citizens followed it. Were silver coins only used in the cities, with trades of goods still used in the country?

Debates over the Effects of the Mongol Invasion

Halperin’s and Sakharov’s articles offer different historical intepretations of the reception and effects of the Mongol invasion in Rus’. Halperin argues that, contrary to teachings perpetuated by the Church, the Rus adapted many aspects of Mongolian life which advanced Rus’ society. For instance, during the Mongol occupation, Rus’ society learned to use the Mongols’ efficient military structure and postal service. The Mongols also “rerouted the fur trade to extract greater revenue” (Halperin 106) for Rus’, thus assisting the culture they had conquered. Halperin makes the point, however, that the Mongols did not force every aspect of their culture onto the Rus’ people, such as their religion. Such an interpretation portrays the Mongol invasion as a kind and enriching period in Rus’ history. On the other hand, Sakharov, in a study of Rus’ culture after the Mongol occupation ended, argues that the Mongols had no positive effect on Rus’. He explains that the Mongols, in taking away Rus’ best craftsmen, created centuries of a Rus’ with inferior architecture. Sakharov then contends that, after the Mongols left, Rus’ culture became much more sophisticated and enlightened, thus underscoring the dark period that had been the Mongols’ reign.

Sakharov writes, “Reborn and developing Russian culture regained its national character in full. The Mongol-Tartars enriched it with nothing whatever, and their influence was quite insignificant in practice” (Sakharov 138). I find this claim to be a little too broad and definitive to be taken as fact. Even disregarding the period after the occupation, the Mongol invasion was clearly significant in its empowering of Moscow and ultimate depowering of Kiev. But moreover, the fact that Rus’ culture exploded in literature and architecture after the occupation also signfies that the Mongols affected Rus’. Perhaps, Rus’ culture wouldn’t have advanced as quickly as it did if the Mongols had not stunted it (if indeed they did stunt it) for so long.

I wonder how the effects Mongol occupation is viewed in other parts of the world. Does the Middle-East and China contend that the Mongols had a positive or negative impact on their cultures? Furthermore, do different geographic sections of Russia today claim different interpretations about the Mongol invasions?

The “Ideal Christian,” according to Feodosii

The Life of St. Theodosius teaches us that the Russian Orthodox Church had nearly impossible standards for the “Ideal Christian.” According to the Chronicles, St. Theodosius–also known as Feodosii–was a child whose love for God led him to withstand a life of social exclusion and horrible abuse from his mother. Feodosii’s mother continuously bought him nice clothes, but he always gave them away to the poor, preferring not to exhibit his own wealth in order to be closer to God. His mother also beat him over and over again as he tried to bake loaves for the church or run away to learn more about God, but Feodosii’s faith remained steadfast. Finally, his total devotion to God, exhibited by his lonely, pained life, led the monks to accept him into their monastery.

This story teaches that the “Ideal Christian” should retain his faith in God no matter the physical, mental, or emotional costs. But even more drastically, it teaches that these losses and pains lead to a better relationship with God than a happier, more balanced life might. Feodosii’s adamant refusal to wear nice clothes or to fight back against his abusive mother were signs of his complete devotion to God. Even once he enters the monastery, Feodosii’s life is still hapless: “Thus he humbled himself by self-denial in every way and tormented his body with labors and abstinence so that the venerable Antonji and great Nikon marveled at his meekness and submissiveness and at such virtue, steadfastness, and good cheer [] a youth” (“The Life of St. Theodosius”). Here, we see that the life of a monk–the life of one who is closest to God–is filled with physical pain, denial of all pleasures, and submissiveness of character.

If the Russian Orthodox Church venerated St. Theodosius lifestyle, then did it expect the same type of character from all its followers? In class today, we discussed how the law code worked both to enforce Christianity and to build up a strong, structured civilization. While the ideals of self-denial and submissiveness which St. Theodosius exhibited might also have helped create a civilization of loyal, submissive citizens, these characteristics might also inhibit cultural advancements because they stunt creative thinking and personal desires. I wonder if such a strict, painful lifestyle was really beneficial–let alone attainable–to Rus civilization at this time.

Disappearing Culture: Indigenous Tribes in the Noril’sk Region of Siberia

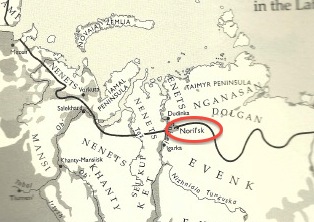

Early in the Soviet era, the government paid little attention to the indigenous tribes of Siberia and did not take into account whether their policies for modernization would have a negative effect on the native peoples. Collectivization and the push for industrialization directly affected the tribes’ economic activity, traditional lifestyle, and the environment in which they lived. Industrialization took place across the Soviet Union, however I have chosen to focus on the city of Noril’sk, located in Krasnoyarsk Krai in northern Siberia, between the Yenisei River and the Taimyr Peninsula. Four main indigenous groups converge in the area of Noril’sk; these groups are the Dolgan, the Nenets, the Nganasan, and the Evenk people. As a result of Soviet collectivization and industrialization policies of the mid-twentieth century, the traditional culture of these indigenous groups altered or faded considerably.

Here is a map showing the geographical location of Noril’sk:

Source: www.thenytimes.com

A key component of analyzing these policies and their effects on these four tribes is to consider the sustainability of these policies with regards to both the environment and the tribes’ traditional ways of life. I would like to clarify that I am defining sustainability as “long-term cultural, economic and environmental health and vitality….together with the importance of linking our social, financial and environmental well-being.” This definition comes from the organization Sustainable Seattle.[1] I argue that Soviet policy towards the indigenous tribes of Siberia in the twentieth century did not promote long-term cultural, economic or environmental vitality, and were therefore unsustainable and unsupportive for the indigenous clans of the region.

Below is a map showing the location of Evenk, Dolgan, Nenet and Nganasan territory relative to Noril’sk and to each other:

The map above shows that Noril’sk serves as a sort of epicenter for these four groups: the Dolgans, Nenets, Nganasans, and Evenks. To learn more about a specific group please click the hyperlinks for further reading. Not only are these four clans close in proximity, but also—like many Siberian tribes—each clan has historically depended on reindeer hunting or herding for their economic livelihood. This does not mean these groups are all the same; they descend from different Eurasian or East Asian ethnic groups and each speak their own native language, among other differences. That being said, each clan experienced similar difficulties adjusting their traditional lifestyles during collectivization and industrialization. There are many ways in which the Soviet Union altered the lives of tribal people in Siberia; collectivization and industrialization are simply the two policies I have chosen to analyze.

Development of Nuclear Waste and Sustainability in Russia

From the radiation of its food to the radiation of its rivers, Russia has built itself into a competitive nuclear power through a tumultuous history of trial and error.[1] Much of the initial funding for Soviet nuclear energy came in an effort to match the United States’ atomic project. But, after developing “the bomb”, nuclear resources in the USSR were applied to a number of areas. These often gave poor results. From such failures, modern Russia has striven to provide a nuclear industry that is safe, clean, and sustainable. In fact, the head of Rosatom’s used fuel management has set a goal of 100% efficiency in the company’s fuel cycle; where all spent fuel is reprocessed into the system — no waste.[4] To understand these, at first, outlandish expectations, we should consider the damages and adaptations that the industry has incurred since its inception in the 1940s.

In the earliest days of the Soviet nuclear industry, one of the most practiced efforts was the irradiation of food. This gave food stuffs a much longer shelf life and they exhibited fewer incidents of contamination due to bacteria or spoiling. But, this also exposed many citizens to harmful levels of radiation after sustained consumption.

In an effort to appease the growing “green movements” in the Soviet Union, Stalin once pursued an aggressive hydro-electric policy. To map the currents in possible rivers, the Soviets had opted to use radioactive isotopes instead of foreign nutrients. These isotopes gave far more accurate readings than the nutrients which would dissolve more quickly in the water. Unfortunately, these tests also irradiated the sites on which they were conducted.

Fantastic Diseases and Where to Find Them

The easiest way to find a fantastic disease in Russia is to do a search of its prisons. Through unsustainable practices such as the failure to continue treatment of highly communicable diseases, such as tuberculosis, once an inmate has been released from prison, tuberculosis has spread in places where it can be easily treated.[1] In order for health in Russian prisons to improve, measures must be taken to ameliorate the inadequate living conditions that spread communicable diseases.[2] The World Health Organization (WHO) created the Health in Prisons Programme (HIPP) in 1995 to fix the major issues of prison healthcare in Europe and create a more sustainable prison health care system. [3] Hopefully, with programs like these in place, Russia will develop a solution to the health care issues that have plagued its society for decades. Continue reading

The “Nature” of Communism

A key aspect of the Soviet Union’s quest for true Communism was becoming waste-free and efficient. Every single resource was utilized for the common good of the state; this included people, materials, machines, and even nature. Unused land was waste, and waste had no place in the Party’s strategy.

Looking back, particularly with today’s heightened emphasis on preserving the environment, it is easy to see the ways in which these policies of brutal extraction from the land would lead to future consequences. The desiccation of the Aral Sea has not only caused serious environmental repercussions, but has also been linked to an increase in medical problems, such as cancer.

I was reading the excerpt on the Aral Sea thinking, “whew, so glad we know better now,” when I realized that thought was dead-wrong. We don’t really know any better. And the biggest environmental offender today? China, the other communist powerhouse from the 20th Century. Chinese cities have some of the worst air and water pollution ratings in the entire world, yet when it was approached with the Kyoto Protocol, which would require it to curb its actions that are so detrimental to the environment, it refused. China’s reasoning was that it was still a “developing nation” and shouldn’t be subjected to such environmental restraints—restraints that other, now-developed nations did not have to adhere to on their path to modernity. Russia would be one such example.

When using this China-parallel it would be easy to conclude that destroying the environment to the states’ benefit is a common facet among Communist states. I’m not sure I can soundly make that assertion, but I don’t think it is a coincidence that the two largest Communist (or near-Communist) countries have committed some of the worst atrocities towards the environment.

Perestroika and 100 wilted flowers

Perestroika and glasnost were terms Gorbachev used to embody his cultural reforms and openness to Western influence. The Chinese, too, had a period of openness. In 1956 Mao said that, “The policy of letting a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend is designed to promote the flourishing of the arts and the progress of science.” This “100 Flowers Movement” was ended in 1957 with political persecutions. Both Communist powers handled political dissonance in the second half of the 20th century differently, with the USSR embracing and the Chinese silencing controversy. Though, to look at it all now, the USSR has been disbanded and China is still heavily controlled by a limited ruling class.

Perestroika and glasnost were terms Gorbachev used to embody his cultural reforms and openness to Western influence. The Chinese, too, had a period of openness. In 1956 Mao said that, “The policy of letting a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend is designed to promote the flourishing of the arts and the progress of science.” This “100 Flowers Movement” was ended in 1957 with political persecutions. Both Communist powers handled political dissonance in the second half of the 20th century differently, with the USSR embracing and the Chinese silencing controversy. Though, to look at it all now, the USSR has been disbanded and China is still heavily controlled by a limited ruling class.

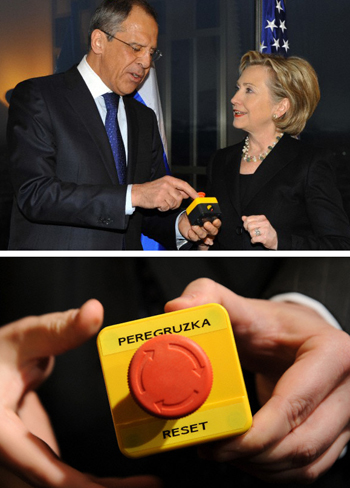

In 2009, Clinton presented Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov with a button that said “Peregruzka — Reset.” The word peregruzka, presented in the Latin and not the Cyrillic alphabet, would translate as “overload” instead of “reset”. Lavrov noticed the error immediately. Given this anecdote, should the United States continue to remain closed to foreign influences and cultures? Russia had a period of openness and voluntary consumption of foreign goods, whereas China had tried to limit all culture through administrative measures. Can the United States thrive on their genetically modified single-crop harvests, or will they eventually need to open themselves up to the world’s hundred flowers?

The Soviet Union: The “Project of the Century?”

“The stagnation of BAM propaganda after its initial formulation indicated the ideological staidness that, by the early 1970s, had gripped the corpus of Soviet governance like some form of mental rigor mortis. While official representations of BAM remained stagnant, the real world around these representations did not. Perhaps this helps to explain the events of the Brezhnev era, a time during which the government refused to acknowledge reality to a greater degree than any regime before it in Soviet history.” – Christopher Ward, Brezhnev’s Folly

The excerpts we read from Brezhnev’s Folly demonstrate how the Baikal-Amur Mainline Railway (BAM) construction project, which Brezhnev proclaimed to be the “project of the century,” perfectly mirrored the social and political environment of the Soviet Union at the time. Social unrest and change was abundant both on BAM worksites as well as across the Union. The organization and oversight of BAM was in the hands of the Komsomol, and ultimately the youth group did not prove equal to the task. In fact, many youths who joined the BAM project did so in order to be a part of the next great product of the Soviet Union, and were sorely disappointed and therefore disillusioned.

There were several ideas behind BAM, most notably to build a transportation system that would connect Western Europe to East Asia, making Russia vital to the expanding economic systems on the two continents. A second driving factor was to spark a new “soviet” flame in the Union’s youth. Like so many of the Soviet’s plans, BAM had the near-opposite effect as officials hoped, and much of the failure can be attributed to the Party’s stubborn blindness towards the reality of the situation.

I chose the title of this post because as I repeatedly read the phrase “project of the century,” I kept asking myself: is the author talking about BAM, or about the Soviet Union? And I realized it applied to both. The idea of creating a communist state was certainly a mighty project, and as we know, a project that ultimately failed. But no one can deny that the Communist Party put forth an immense amount of human, financial and material capital in an attempt to attain their goal. Indeed, one could call their dream the “project of the century.”