William Bishop Owen

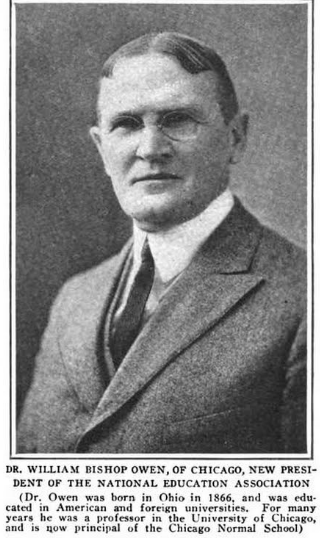

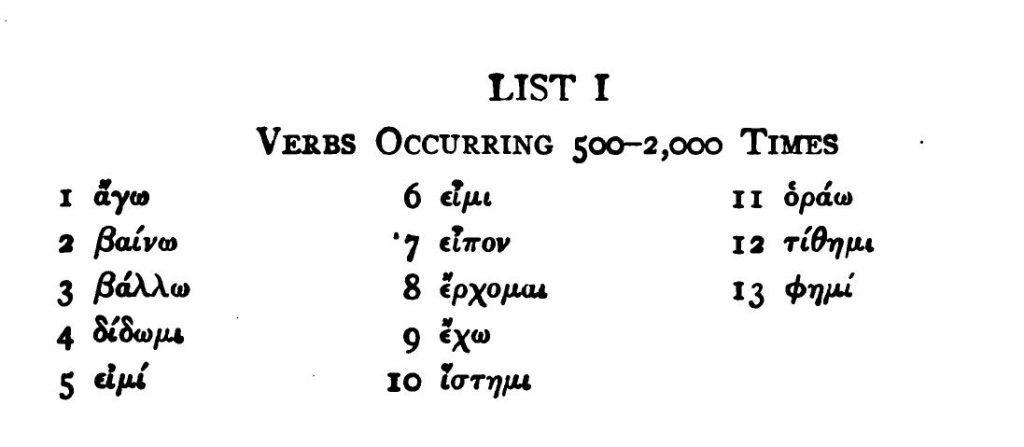

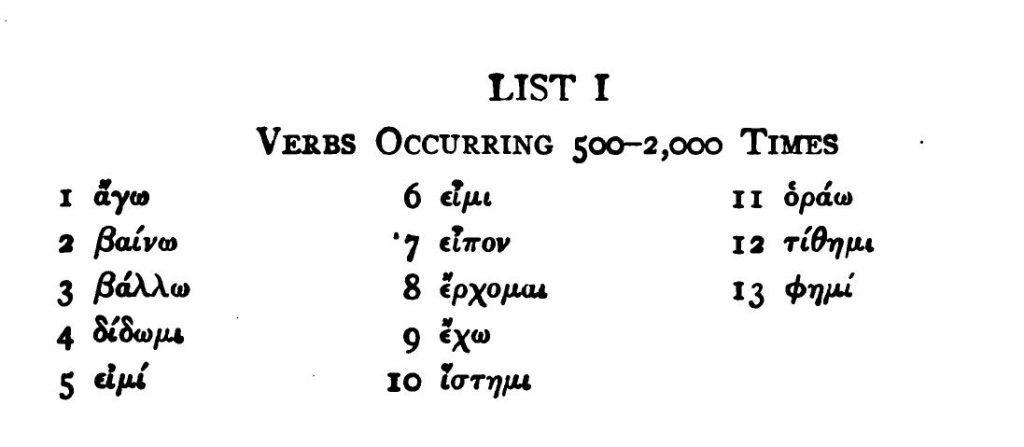

Generations of beginning Homerists have been asked to purchase the little book Homeric Vocabularies by William Bishop Owen and Edgar Johnson Goodspeed. I acquired it in college, and later, when I came to teach Homer, I also asked my students to buy it. It’s a mainstay. The blisteringly critical review by Wm. W. Baker in Classical Review of 1908, however, has convinced me, however, that it is a piece of junk from the student’s point of view. Originally published in 1906, it has been frequently reprinted, and is currently published by the University of Oklahoma Press in a revised edition, copyright 1969. It has lists of words in Homer, organized by frequency. The very first page has an impressive list of verbs occurring 500 to 2,000 times. There are 13 of them, all the greatest hits:

The 13 most common verbs in Homer, from Owen and Goodspeed (1906 edition), p. 3.

Other lists include verbs that occur 200 to 500 times, down to ones that occur 10 to 25 times. Noun lists give those occurring 500 to 1,000 times, down to 10 to 25 times. There are (combined) lists of common pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, and prepositions.

Baker first questions the whole approach of learning vocabulary from lists. Probably better to read fast and widely, he says. True enough. But if you must have lists, at least make the lists in a way that gives the student needed help and doesn’t mislead or make the student’s life more difficult. The review (full text below) points out a number of flaws, only some of which were rectified in the 1969 revision. The main version available on the internet is from 1909, and all these criticisms apply.

- Greek words are not associated with English definitions, which are given only in the back of the book. They should be in parallel columns. Duh! This was fixed in the 1969 revision.

- Related words, and even different forms of the same words, are widely separated (e.g. τανύω, τείνωμ, τιταίνω, which are nos. 151, 275, and 504 respectively).

- Words of similar form but different meaning are not juxtaposed so the student may be put on guard not to confuse them.

- English definitions were haphazardly taken (without attribution) from the English version of Authenrieth’s Homeric Dictionary (1891, now on Perseus), which was old-fashioned and clunky even back in the day. The results are frequently misleading, or just laughable (ἤαβάω, “Am at my youthful prime”).

- Definitions for parallel forms of the same word (e.g. λανθάνω λήθω) are inconsistent.

- Needless synonyms make memorization harder. ἔγχος, “Spear, lance.” Why spear and lance?

- Attic forms, with which most students are more familiar, are not provided for comparison, for words like πρήσσω and θηέομαι. The same goes for words in which Attic meanings vary substantially from Homeric ones, like φοβέω, ἀρκέω, and ἀσκέω.

When I think how many brilliant, dedicated Homerists there are in the world, all the monographs and commentaries that have been published in the last 100 years, the enormous progress made in understanding Homer at an advanced scholarly level, and how no one has thought it worthwhile to create a more effective replacement for this potentially so useful book, it seems to sum up something basic to the culture of classical scholarship. The mind especially boggles at how easy it would be to solve all these problems and add countless improvements in a digital environment. I’m hoping to get my Homer students this spring interested in collaborating on an overhaul for DCC. Ok, here is the full text of Baker’s review in The Classical Review, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Jun., 1908), pp. 128–129:

Homeric Vocabularies: Greek and English Word-Lists for the Study of Homer. By WILLIAM BISHOP OWEN, Ph.D., and EDGAR JOHNSON GOODSPEED, Ph.D. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1906. Pp. viii+ 62. 50 cents, net.

To those who believe in the systematic study of vocabularies, the title of this little book has a hopeful sound. And doubtless the book itself may fulfil its purpose reasonably well in the hands of many teachers. Yet it seems as if it might easily have been made much more useful. The object of such a list should be to enable the student to fix the meaning of as many important words as possible in his mind with the least possible labour. And this can hardly be accomplished with the present book. First of all its arrangement strikes one as faulty. The Greek words and the English are in separate halves of the book, nor do the Greek and their meanings even occupy corresponding places on their respective pages. Much less laborious, certainly, for the learner would have been an arrangement of both on the same page in parallel columns. The words are further separated into three groups, verbs, nouns, and, thirdly, the other parts of speech together, and in each group its members are separated into a half dozen lists according to the frequency of their occurrence in Homer. This plan has some advantages, but, on the other hand, the labour of memorizing is unquestionably much increased: related words and even different forms of the same word are widely separated (e.g. τανύω, τείνω, τιταίνω, are Nos. 151, 275, 504 respectively); nor are words of similar form but different meaning placed in proper juxtaposition so that the student may be put on his guard and not confuse them.

The choice of meanings, too, is not above reproach. They are, we may say, almost entirely chosen from the English translation of Autenrieth’s Homeric Dictionary, as but a brief glance will show, and although meanings of words may not be subject to copyright, it might have been well if the editors had acknowledged their indebtedness. Unfortunately, also, they are not always chosen wisely. For example, τελέθω is ‘Am become, assume,’ where ‘assume’ is worse than useless; so with πειρητίζω, ‘Test, sound.’ For τρωπάω (a word which, so far as Ebeling’s Lexicon shows, does not occur the ten times the editors claim for it) we have ‘Change, vary’—entirely unsuitable meanings except for a single passage. Again one might reasonably expect to find identical meanings given for parallel forms of the same word. But quite the opposite is often the case. Thus λανθάνω is ‘Escape notice, forget,’ λήθω is only ‘Escape notice’; κεδάννυμι is ‘ Scatter,’ σκεδάννυμι, and σκίνδαμαι, ‘Scatter, disperse,’ for no apparent reason. And in general why should so many useless synonyms be given? Why should ἔγχος be ‘Spear, lance’ or θύρη ‘Door, gate’? It seems obvious that unless a word has more than one distinct signification, only a single meaning should be set down. For if the meanings are to be committed absolutely to memory one is easier to learn than two; if not, the method of wide and rapid reading would seem preferable to fooling with a word-list. Among other meanings susceptible of improvement are those of μεγάθυμος, ‘Great-hearted,’—a mere school-boy’s rendering—and ἡβάω, ‘Am at my youthful prime,’—enough to make even a school-boy laugh. All of which goes to show that the meanings must have been selected in a very haphazard fashion.

Additional information would be desirable in some cases: thus the meaning of active and middle of such verbs as ἅπτω and λανθάνω ought to have been differentiated. To have the Attic forms given in words like πρήσσω and θηέομαι would be helpful, though it may not be necessary; so also the Attic meaning, where this varies widely from the Homeric, as in φοβέω, ἀρκέω, and ἀσκέω. And none of these additions would overload the book.

I have noticed a few misprints: δύνω occurs twice (Nos. 46 and 201, and with varying meanings in the two places); No. 407, κορέω, ‘Sweep ‘—a ἅπαξ λεγόμενον— should be κορέννυμι, ‘Satisfy’; at No. 474, for ‘Cover,’ read ‘Cower’; at No. 521, for ‘place,’ read ‘plan’; noun Νo. 198 should be defined ‘olive-oil,’ not ‘olive, oil.’

Wm. W. BAKER.

Haverford College